Prisoner of war

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held

Belligerents hold prisoners of war in custody for a range of legitimate and illegitimate reasons, such as isolating them from the enemy combatants still in the field (releasing and repatriating them in an orderly manner after hostilities), demonstrating military victory, using civilians to deter attacks on active military targets, punishing them, prosecuting them for war crimes, exploiting them for their labour, recruiting or even conscripting them as their own combatants, collecting military and political intelligence from them, or indoctrinating them in new political or religious beliefs.[1]

Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, prisoners of war are automatically granted the enhanced status of protected persons, alongside certain civilians and enemy combatants who are hors de combat (i.e., out of the fight).[2]

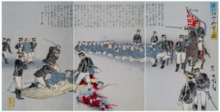

Ancient times

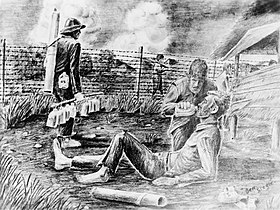

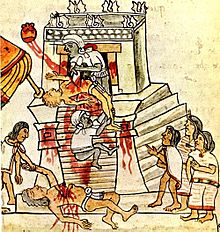

For a large part of human history, prisoners of war would most often be either slaughtered or

Typically, victors made little distinction between enemy combatants and enemy civilians, although they were more likely to spare women and children. Sometimes the purpose of a battle, if not of a war, was to capture women, a practice known as

In the fourth century AD, Bishop Acacius of Amida, touched by the plight of Persian prisoners captured in a recent war with the Greek Empire, who were held in his town under appalling conditions and destined for a life of slavery, took the initiative in ransoming them by selling his church's precious gold and silver vessels and letting them return to their country. For this he was eventually canonized.[6]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

According to legend, during

King Henry V's English army killed many French prisoners of war after the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.[8] This was done in retaliation for the French killing of the boys and other non-combatants handling the baggage and equipment of the army, and because the French were attacking again and Henry was afraid that they would break through and free the prisoners who would rejoin the fight against the English.

In the later

Likewise, the inhabitants of conquered cities were frequently massacred during Christians'

In the 13th century the expanding

The

During the

Modern times

In Europe, the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly centralized, in the time period between the 16th and late 18th century. Whereas prisoners of war had previously been regarded as the private property of the captor, captured enemy soldiers became increasingly regarded as the property of the state. The European states strove to exert increasing control over all stages of captivity, from the question of who would be attributed the status of prisoner of war to their eventual release. The act of surrender was regulated so that it, ideally, should be legitimized by officers, who negotiated the surrender of their whole unit.[20] Soldiers whose style of fighting did not conform to the battle line tactics of regular European armies, such as Cossacks and Croats, were often denied the status of prisoners of war.[21]

In line with this development the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly regulated in international treaties, particularly in the form of the so-called cartel system, which regulated how the exchange of prisoners would be carried out between warring states.[22] Another such treaty was the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years' War. This treaty established the rule that prisoners of war should be released without ransom at the end of hostilities and that they should be allowed to return to their homelands.[23]

There also evolved the

European settlers captured in North America

Early historical narratives of captured European settlers, including perspectives of literate women captured by the

French Revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars

The earliest known purpose-built

During the Battle of Leipzig both sides used the city's cemetery as a lazaret and prisoner camp for around 6,000 POWs who lived in the burial vaults and used the coffins for firewood. Food was scarce and prisoners resorted to eating horses, cats, dogs or even human flesh. The bad conditions inside the graveyard contributed to a city-wide epidemic after the battle.[25][26]

Prisoner exchanges

The extensive period of conflict during the

American Civil War

At the start of the American Civil War a system of paroles operated. Captives agreed not to fight until they were officially exchanged. Meanwhile, they were held in camps run by their own army where they were paid but not allowed to perform any military duties.

Amelioration

During the 19th century, there were increased efforts to improve the treatment and processing of prisoners. As a result of these emerging conventions, a number of international conferences were held, starting with the Brussels Conference of 1874, with nations agreeing that it was necessary to prevent inhumane treatment of prisoners and the use of weapons causing unnecessary harm. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new conventions being adopted and becoming recognized as international law that specified that prisoners of war be treated humanely and diplomatically.

Hague and Geneva Conventions

Chapter II of the Annex to the

Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention protects captured

The

However, nations vary in their dedication to following these laws, and historically the treatment of POWs has varied greatly. During World War II,

Qualifications

To be entitled to prisoner-of-war status, captured persons must be

Thus, uniforms and badges are important in determining prisoner-of-war status under the Third Geneva Convention. Under

The criteria are applied primarily to international armed conflicts. The application of prisoner of war status in non-international armed conflicts like

Rights

Under the Third Geneva Convention, prisoners of war (POW) must be:

- Treated humanely with respect for their persons and their honor

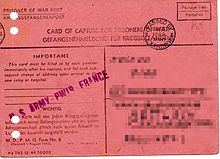

- Able to inform their next of kin and the International Committee of the Red Cross of their capture

- Allowed to communicate regularly with relatives and receive packages

- Given adequate food, clothing, housing, and medical attention

- Paid for work done and not forced to do work that is dangerous, unhealthy, or degrading

- Released quickly after conflicts end

- Not compelled to give any information except for name, age, rank, and service number[32]

In addition, if wounded or sick on the battlefield, the prisoner will receive help from the International Committee of the Red Cross.[33]

When a country is responsible for breaches of prisoner of war rights, those accountable will be punished accordingly. An example of this is the

U.S. Code of Conduct and terminology

When a military member is taken prisoner, the Code of Conduct reminds them that the chain of command is still in effect (the highest ranking service member eligible for command, regardless of service branch, is in command), and requires them to support their leadership. The Code of Conduct also requires service members to resist giving information to the enemy (beyond identifying themselves, that is, "name, rank, serial number"), receiving special favours or parole, or otherwise providing their enemy captors aid and comfort.

Since the Vietnam War, the official U.S. military term for enemy POWs is EPW (Enemy Prisoner of War). This name change was introduced in order to distinguish between enemy and U.S. captives.[35]

In 2000, the U.S. military replaced the designation "Prisoner of War" for captured American personnel with "Missing-Captured". A January 2008 directive states that the reasoning behind this is since "Prisoner of War" is the international legal recognized status for such people there is no need for any individual country to follow suit. This change remains relatively unknown even among experts in the field and "Prisoner of War" remains widely used in the Pentagon which has a "POW/Missing Personnel Office" and awards the Prisoner of War Medal.[36][37]

World War I

During World War I, about eight million men surrendered and were held in POW camps until the war ended. All nations pledged to follow the Hague rules on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and in general the POWs had a much higher survival rate than their peers who were not captured.

The

There was much harsh treatment of POWs in Germany, as recorded by the American ambassador (prior to America's entry into the war), James W. Gerard, who published his findings in "My Four Years in Germany". Even worse conditions are reported in the book "Escape of a Princess Pat" by the Canadian George Pearson. It was particularly bad in Russia, where starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; a quarter of the over 2 million POWs held there died.

The Ottoman Empire often treated prisoners of war poorly[citation needed]. Some 11,800 British soldiers, most from the British Indian Army, became prisoners after the five-month Siege of Kut, in Mesopotamia, in April 1916. Many were weak and starved when they surrendered and 4,250 died in captivity.[46]

During the

Release of prisoners

At the end of the war in 1918 there were believed to be 140,000 British prisoners of war in Germany, including thousands of internees held in neutral Switzerland.

On 13 December 1918, the armistice was extended and the Allies reported that by 9 December 264,000 prisoners had been repatriated. A very large number of these had been released en masse and sent across Allied lines without any food or shelter. This created difficulties for the receiving Allies and many ex-prisoners died from exhaustion. The released POWs were met by cavalry troops and sent back through the lines in lorries to reception centres where they were refitted with boots and clothing and dispatched to the ports in trains.

Upon arrival at the receiving camp the POWs were registered and "boarded" before being dispatched to their own homes. All

The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries & hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage.

During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant Officers & Men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

We are thankful that this longed for day has arrived, & that back in the old Country you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home & to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return.

— George R.I.[50]

While the Allied prisoners were sent home at the end of the war, the same treatment was not granted to

World War II

Historian Niall Ferguson, in addition to figures from Keith Lowe, tabulated the total death rate for POWs in World War II as follows:[52][53]

| Percentage of POWs that died | |

|---|---|

| Chinese POWs held by Japanese | Almost 100%[54] |

| USSR POWs held by Germans | 57.5% |

| German POWs held by Yugoslavs | 41.2% |

| German POWs held by USSR | 35.8% |

| American POWs held by Japanese | 33.0% |

| German POWs held by Eastern Europeans | 32.9% |

| British POWs held by Japanese | 24.8% |

| French POWs held by Germans | 4.1% |

| British POWs held by Germans | 3.5% |

| German POWs held by French | 2.6% |

| American POWs held by Germans | 1.2% |

| German POWs held by Americans | 0.2% |

| German POWs held by British | <0.1% |

Treatment of POWs by the Axis

Empire of Japan

The

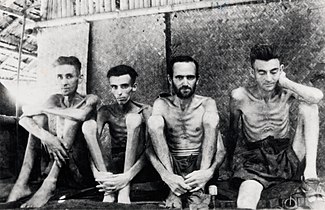

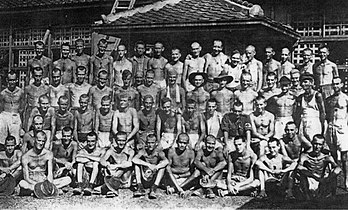

Prisoners of war from China, the United States, Australia, Britain, Canada, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the Philippines held by Japanese imperial armed forces were subject to murder, beatings, extrajudicial punishment, brutal treatment,

According to the findings of the Tokyo Tribunal, the death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1 percent, seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians.[61] The death rate of Chinese was much higher. Thus, while 37,583 prisoners from the United Kingdom, Commonwealth, and Dominions, 28,500 from the Netherlands, and 14,473 from the United States were released after the surrender of Japan, the number for the Chinese was only 56.[61][62] The 27,465 United States Army and United States Army Air Forces POWs in the Pacific Theater had a 40.4 per cent death rate.[63] The War Ministry in Tokyo issued an order at the end of the war to kill the remaining POWs.[64]

No direct access to the POWs was provided to the

Allied POW camps and ship-transports were sometimes accidental targets of Allied attacks. The number of deaths which occurred when Japanese "hell ships"—unmarked transport ships in which POWs were transported in harsh conditions—were attacked by U.S. Navy submarines was particularly high. Gavan Daws has calculated that "of all POWs who died in the Pacific War, one in three was killed on the water by friendly fire".[66] Daws states that 10,800 of the 50,000 POWs shipped by the Japanese were killed at sea[67] while Donald L. Miller states that "approximately 21,000 Allied POWs died at sea, about 19,000 of them killed by friendly fire."[68]

Life in the POW camps was recorded at great risk to themselves by artists such as Jack Bridger Chalker, Philip Meninsky, Ashley George Old, and Ronald Searle. Human hair was often used for brushes, plant juices and blood for paint, toilet paper as the "canvas". Some of their works were used as evidence in the trials of Japanese war criminals.

Female prisoners (detainees) at Changi Prison in Singapore, recorded their ordeal in seemingly harmless prison quilt embroidery.[69]

Research into the conditions of the camps has been conducted by The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.[70]

-

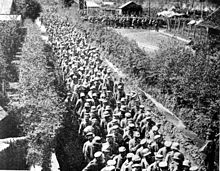

Troops of the Suffolk Regiment surrendering to the Japanese, 1942

-

Many US and Filipino POWs died on the Bataan Death March, in May 1942

-

Water colour sketch of "Dusty" Rhodes by Ashley George Old

-

Australian and Dutch POWs at Tarsau, Thailand in 1943

-

U.S. Navy nurses rescued from Los Baños Internment Camp, March 1945

-

Allied prisoners of war at Aomori camp near Yokohama, Japan, waving flags of the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands in August 1945

-

Canadian POWs at the Liberation of Hong Kong

-

Malnourished Australian POWs forced to work at the Aso mining company, August 1945

-

POW art depicting Cabanatuan prison camp, produced in 1946

-

Australian POWshin guntosword in 1943

-

Captured soldiers of the British Indian Army executed by the Japanese

Germany

French soldiers

After the French armies surrendered in summer 1940, Germany seized two million French prisoners of war and sent them to camps in Germany. About one third were released on various terms. Of the remainder, the officers and non-commissioned officers were kept in camps and did not work. The privates were sent out to work. About half of them worked for German agriculture, where food supplies were adequate and controls were lenient. The others worked in factories or mines, where conditions were much harsher.[71]

Western Allies' POWs

Germany and Italy generally treated prisoners from the

Only a small proportion of western Allied POWs who were

A small number of Allied personnel were sent to concentration camps, for a variety of reasons including being Jewish.

Information on conditions in the stalags is contradictory depending on the source. Some American POWs claimed the Germans were victims of circumstance and did the best they could, while others accused their captors of brutalities and forced labour. In any case, the prison camps were miserable places where food rations were meager and conditions squalid. One American admitted "The only difference between the stalags and concentration camps was that we weren't gassed or shot in the former. I do not recall a single act of compassion or mercy on the part of the Germans." Typical meals consisted of a bread slice and watery potato soup which was still more substantial than what Soviet POWs or concentration camp inmates received. Another prisoner stated that "The German plan was to keep us alive, yet weakened enough that we wouldn't attempt escape."[78]

As the Red Army approached some POW camps in early 1945, German guards forced western Allied POWs to walk long distances towards central Germany, often in extreme winter weather conditions.[79] It is estimated that, out of 257,000 POWs, about 80,000 were subject to such marches and up to 3,500 of them died as a result.[80]

Italian POWs

In September 1943 after the Armistice, Italian officers and soldiers in many places waiting for orders were arrested by Germans and Italian fascists and taken to internment camps in Germany or Eastern Europe, where they were held for the duration of the war. The International Red Cross could do nothing for them, as they were not regarded as POWs, but the prisoners held the status of "

Eastern European POWs

Between 1941 and 1945 the Axis powers took about 5.7 million Soviet prisoners. About one million of them were released during the war, in that their status changed but they remained under German authority. A little over 500,000 either escaped or were liberated by the Red Army. Some 930,000 more were found alive in camps after the war. The remaining 3.3 million prisoners (57.5% of the total captured) died during their captivity.

The Germans officially justified their policy on the grounds that the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention. Legally, however, under article 82 of the

Romania

Soviet POWs

Between 1941 and 1944, 91,060 Soviet prisoners of war were captured by the

In the winter of 1941/1942, the conditions of the POW camps were unsatisfactory, leading to the deaths of prisoners due to various diseases. The conditions were improved in 1942 when, by order of Marshal Ion Antonescu, the organizations leading the camps were to permanently control how the prisoners were accommodated, cared for, fed, and used. Due to some problems that arose with the food allowance in 1942, it was decided that the prisoners were to be fed like the Romanian troops, with an allocated 30 lei per soldier per day.[90]

In accordance with Article 27 of the Geneva Convention, the POWs were used in various productive activities. In return for providing work, the prisoners were granted payment and accommodation, as well as free time for cleaning, rest, and religious or other activities by their employers, according to the contracts signed with the commanders of the prison camps. The main workplaces for prisoners were in agriculture and industrial enterprises, but also in forestry, civil works, and in service of the POW camps.[90]

For correspondence with their families, the prisoners were provided with postcards. However, most of these were not used as the POWs feared reprisals from the Soviet authorities upon learning that they were prisoners in Romania. The punishment of POWs in the Romanian camps was applied following the regulations of the Romanian Army. Executions by firing squad were few. The escapees who were caught and did not commit any acts of sabotage or espionage were tried by court-martial and sentenced to prison terms from 3-6 months to several years. After 23 August 1944, the Soviet POWs were handed over to the Soviet headquarters.[90]

Western Allies' POWs

The first Americans were captured in Romania following

In the spring of 1944, with the increasing number of American and British prisoners due to the

Treatment of POWs by the Soviet Union

Germans, Romanians, Italians, Hungarians, Finns

According to some sources, the Soviets captured 3.5 million

German soldiers were kept as forced labour for many years after the war. The last German POWs like Erich Hartmann, the highest-scoring fighter ace in the history of aerial warfare, who had been declared guilty of war crimes but without due process, were not released by the Soviets until 1955, two years after Stalin died.[96]

Polish

As a result of the

Of the 230,000 Polish prisoners of war taken by the Soviet army, only 82,000 survived.[99]

Japanese

After the Soviet–Japanese War, 560,000 to 760,000 Japanese prisoners of war were captured by the Soviet Union. The prisoners were captured in Manchuria, Korea, South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, then sent to work as forced labour in the Soviet Union and Mongolia.[100] An estimated 60,000 to 347,000 of these Japanese prisoners of war died in captivity.[101][102][103][104]

Americans

Stories that circulated during the Cold War claimed 23,000 Americans held in German POW camps had been seized by the Soviets and never been repatriated. The claims had been perpetuated after the release of people like John H. Noble. Careful scholarly studies demonstrated that this was a myth based on the misinterpretation of a telegram about Soviet prisoners held in Italy.[105]

Treatment of POWs by the Western Allies

Germans

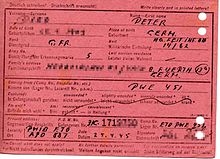

of a German General

(Front- and Backside)

During the war, the armies of Western Allied nations such as Australia, Canada, the UK and the US

In Britain, German prisoners, particularly higher-ranked officers, were housed in luxurious buildings where listening devices were installed. A considerable amount of military intelligence was gained from eavesdropping on what the officers believed were private casual conversations. Much of the listening was carried out by German refugees, in many cases Jews. The work of these refugees in contributing to the Allied victory was declassified over half a century later.[109]

In February 1944, 59.7% of POWs in America were employed. This relatively low percentage was due to problems setting wages that would not compete against those of non-prisoners, to union opposition, as well as concerns about security, sabotage, and escape. Given national manpower shortages, citizens and employers resented the idle prisoners, and efforts were made to decentralize the camps and reduce security enough that more prisoners could work. By the end of May 1944, POW employment was at 72.8%, and by late April 1945 it had risen to 91.3%. The sector that made the most use of POW workers was agriculture. There was more demand than supply of prisoners throughout the war, and 14,000 POW repatriations were delayed in 1946 so prisoners could be used in the spring farming seasons, mostly to thin and block

Towards the end of the war in Europe, as large numbers of Axis soldiers surrendered, the US created the designation of Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF) so as not to treat prisoners as POWs. A lot of these soldiers were kept in open fields in makeshift camps in the Rhine valley (Rheinwiesenlager). Controversy has arisen about how Eisenhower managed these prisoners.[111] (see Other Losses).

After the surrender of Germany in May 1945, the POW status of the German prisoners was in many cases maintained, and they were for several years used as public labourers in countries such as the UK and France. Many died when forced to clear minefields in countries such as Norway and France. "By September 1945 it was estimated by the French authorities that two thousand prisoners were being maimed and killed each month in accidents".[112][113]

In 1946, the UK held over 400,000 German POWs, many having been transferred from POW camps in the US and Canada. They were employed as labourers to compensate for the lack of manpower in Britain, as a form of war reparation.[114][115] A public debate ensued in the U.K. over the treatment of German prisoners of war, with many in Britain comparing the treatment to the POWs to slave labour.[116] In 1947, the Ministry of Agriculture argued against repatriation of working German prisoners, since by then they made up 25 percent of the land workforce, and it wanted to continue having them work in the UK until 1948.[116]

The "London Cage", an MI19 prisoner of war facility in London used during and immediately after the war to interrogate prisoners before sending them to prison camps, was subject to allegations of torture.[117]

After the German surrender, the International Red Cross was prohibited from providing aid, such as food or prisoner visits, to POW camps in Germany. However, after making appeals to the Allies in the autumn of 1945, the Red Cross was allowed to investigate the camps in the British and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as providing relief to the prisoners held there.[118] On 4 February 1946, the Red Cross was also permitted to visit and assist prisoners in the US occupation zone of Germany, although only with very small quantities of food. "During their visits, the delegates observed that German prisoners of war were often detained in appalling conditions. They drew the attention of the authorities to this fact, and gradually succeeded in getting some improvements made".[118]

POWs were also transferred among the Allies, with for example 6,000 German officers transferred from Western Allied camps to the Soviets and subsequently imprisoned in the

The United States handed over 740,000 German prisoners to France, which was a Geneva Convention signatory but which used them as forced labourers. Newspapers reported that the POWs were being mistreated; Judge

have done or are doing some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for. The French are so violating the Geneva Convention in the treatment of prisoners of war that our command is taking back prisoners sent to them. We are prosecuting plunder and our Allies are practising it.[124][125]

Hungarians

Japanese

Although thousands of Japanese servicemembers were taken prisoner, most fought until they were killed or committed suicide. Of the 22,000 Japanese soldiers present at the beginning of the Battle of Iwo Jima, over 20,000 were killed and only 216 were taken prisoner.[128] Of the 30,000 Japanese troops that defended Saipan, fewer than 1,000 remained alive at battle's end.[129] Japanese prisoners sent to camps fared well; however, some were killed when attempting to surrender or were massacred[130] just after doing so (see Allied war crimes during World War II in the Pacific). In some instances, Japanese prisoners were tortured through a variety of methods.[131] A method of torture used by the Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) included suspending prisoners by the neck in wooden cages until they died.[132] In very rare cases, some were beheaded by sword, and a severed head was once used as a football by Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) soldiers.[133]

After the war, many Japanese POWs were kept on as Japanese Surrendered Personnel until mid-1947 by the Allies. The JSP were used until 1947 for labour purposes, such as road maintenance, recovering corpses for reburial, cleaning, and preparing farmland. Early tasks also included repairing airfields damaged by Allied bombing during the war and maintaining law and order until the arrival of Allied forces in the region.

Italians

In 1943, Italy overthrew Mussolini and became an Allied co-belligerent. This did not change the status of many Italian POWs, retained in Australia, the UK and US due to labour shortages.[134]

After Italy surrendered to the Allies and declared war on Germany, the United States initially made plans to send Italian POWs back to fight Germany. Ultimately though, the government decided instead to loosen POW work requirements prohibiting Italian prisoners from carrying out war-related work. About 34,000 Italian POWs were active in 1944 and 1945 on 66 US military installations, performing support roles such as quartermaster, repair, and engineering work as Italian Service Units.[110]

Cossacks

On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the USSR.[135] The interpretation of this agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets (Operation Keelhaul) regardless of their wishes. The forced repatriation operations took place in 1945–1947.[136]

Post-World War II

During the Korean War, the North Koreans developed a reputation for severely mistreating and torturing prisoners of war (see Treatment of POWs by North Korean and Chinese forces). Their POWs were housed in three camps, according to their potential usefulness to the North Korean army. Peace camps and reform camps were for POWs that were either sympathetic to the cause or who had valued skills that could be useful to the North Korean military; these enemy soldiers were indoctrinated and sometimes conscripted into the North Korean army. While POWs in peace camps were reportedly treated with more consideration,[137] regular prisoners of war were usually treated very poorly.

The 1952 Inter-Camp POW Olympics were held from 15 to 27 November 1952 in Pyuktong, North Korea. The Chinese hoped to gain worldwide publicity, and while some prisoners refused to participate, some 500 POWs of eleven nationalities took part.[138] They came from all the North Korean prison camps and competed in football, baseball, softball, basketball, volleyball, track and field, soccer, gymnastics, and boxing.[138] For the POWs, this was also an opportunity to meet with friends from other camps. The prisoners had their own photographers, announcers, and even reporters, who after each day's competition published a newspaper, the "Olympic Roundup".[139]

At the end of the First Indochina War, of the 11,721 French soldiers taken prisoner after the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and led by the Viet Minh on death marches to distant POW camps, only 3,290 were repatriated four months later.[140]

During the

As in previous conflicts, speculation existed, without evidence, that a handful of American pilots captured during the Korean and Vietnam wars were transferred to the Soviet Union and never repatriated.[142][143][144]

Regardless of regulations determining treatment of prisoners, violations of their rights continue to be reported. Many cases of POW massacres have been reported in recent times, including the murder of Israeli prisoners of war in the 1973

Indian intervention in the

In 1982, during the Falklands War, prisoners were well-treated in general by both sides, with military commanders dispatching enemy prisoners back to their homelands in record time.[145]

In 1991, during the Gulf War, American, British, Italian, and Kuwaiti POWs (mostly crew members of downed aircraft and special forces) were tortured by the Iraqi secret police. An American military doctor, Major Rhonda Cornum, a 37-year-old flight surgeon captured when her Blackhawk UH-60 was shot down, was also subjected to sexual abuse.[146]

During the

In 2001, reports emerged concerning two POWs that India had taken during the

The last prisoners of the 1980–1988 Iran–Iraq War were exchanged in 2003.[148]

During the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, Ukrainian POWs have described being tortured by Russian forces using electrocution, beatings, and sexual abuse. Both sides of the conflict forced prisoners to be naked as a humiliating punishment.[149]

Numbers of POWs

This section lists nations with the highest number of POWs since the start of World War II and ranked by descending order. These are also the highest numbers in any war since the

| Armies | Number of POWs held in captivity | Name of conflict |

|---|---|---|

|

World War II | |

| 5.7 million taken by million died in captivity (56–68%))[151]

|

World War II (total) | |

| 1,800,000 taken by Germany | World War II | |

| 675,000 (420,000 taken by Germany; 240,000 taken by the Soviets in 1939; 15,000 taken by Germany in Warsaw in 1944) | World War II | |

| ≈200,000 (135,000 taken in Europe, does not include Pacific or Commonwealth figures) | World War II | |

| ≈175,000 taken by Coalition of the Gulf War | Persian Gulf War

| |

|

World War II | |

| ≈130,000 (95,532 taken by Germany) | World War II | |

|

World War II |

In popular culture

Films and television

- 1971

- Andersonville

- Another Time, Another Place

- As Far as My Feet Will Carry Me

- Blood Oath

- The Bridge on the River Kwai

- The Brylcreem Boys

- The Colditz Story

- Danger Within

- The Deer Hunter

- Empire of the Sun

- Escape from Sobibor

- Escape to Athena

- Escape to Victory

- Faith of My Fathers

- Grand Illusion

- The Great Escape

- The Great Raid

- Hanoi Hilton

- Hart's War

- Hogan's Heroes

- Homeland

- Land of Mine

- Katyń

- King Rat

- The McKenzie Break

- Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

- Missing in Action

- The One That Got Away

- P.O.W.- Bandi Yuddh Ke

- The Password is Courage

- Paradise Road

- The Pianist

- The Purple Heart

- The Railway Man

- Rambo: First Blood Part II

- Rescue Dawn

- The Report

- Slaughterhouse Five

- Some Kind of Hero

- Stalag 17

- Summer of My German Soldier

- T-34

- Tea with Mussolini

- Tenko

- Three Came Home

- To End All Wars

- Unbroken

- Uncommon Valor

- Von Ryan's Express

- The Walking Dead

- Who Goes Next?

- The Wooden Horse

See also

- Prisoner-of-war camp

- 13th Psychological Operations Battalion

- 1952 POW olympics

- Armenian POWs during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War

- Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–1924)

- Civilian Internee

- Duty to escape

- Elsa Brändström

- Extermination of Soviet prisoners of war by Nazi Germany

- German prisoners of war in the United States

- Illegal combatant

- Korean War POWs detained in North Korea

- Laws of war

- List of notable prisoners of war

- List of prisoner-of-war escapes

- Medal for civilian prisoners, deportees and hostages of the 1914–1918 Great War

- Military Chaplain#Noncombatant status

- Prisoner of war mail

- Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project (RULAC)

- Vietnam War POW/MIA issue

- World War II Radio Heroes: Letters of Compassion

References

Notes

- ^ Compare Harper, Douglas. "prisoner". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 10 October 2021. – "Captives taken in war have been called prisoners since mid-14c.; phrase prisoner of war dates from 1630s".

- ^ According to the Dialogus Miraculorum by Caesarius of Heisterbach, Arnaud Amalric was only reported to have said that.

- North African Campaign (World War II)

Citations

- ^ John Hickman (2002). "What is a Prisoner of War For". Scientia Militaria. 36 (2). Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Doctors Without Borders.

- ^ Wickham, Jason (2014) The Enslavement of War Captives by the Romans up to 146 BC, University of Liverpool PhD Dissertation. "The Enslavement of War Captives by the Romans to 146 BC" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015. Wickham 2014 notes that for Roman warfare the outcome of capture could lead to release, ransom, execution or enslavement.

- ^ "The Roman Gladiator" Archived 26 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The University of Chicago – "Originally, captured soldiers had been made to fight with their own weapons and in their particular style of combat. It was from these conscripted prisoners of war that the gladiators acquired their exotic appearance, a distinction being made between the weapons imagined to be used by defeated enemies and those of their Roman conquerors. The Samnites (a tribe from Campania which the Romans had fought in the fourth and third centuries BC) were the prototype for Rome's professional gladiators, and it was their equipment that first was used and later adopted for the arena. [...] Two other gladiatorial categories also took their name from defeated tribes, the Galli (Gauls) and Thraeces (Thracians)."

- ^ Eisenberg, Bonnie; Ruthsdotter, Mary (1998). "History of the Women's Rights Movement". www.nwhp.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018.

- ^ "Church Fathers: Church History, Book VII (Socrates Scholasticus)". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ISBN 0-14-051312-4.

- ISBN 0-521-84792-3.

- ISBN 0-19-520912-5.

- ^ "Samurai, Warfare and the State in Early Medieval Japan" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Journal of Japanese Studies.

- ^ "Central Asian world cities". Faculty.washington.edu. 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Meyer, Michael C. and William L. Sherman. The Course of Mexican History. Oxford University Press, 5th ed. 1995.

- ^ Hassig, Ross (2003). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas". Arqueología Mexicana, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Harner, Michael (April 1977). "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice". Natural History. Latinamericanstudies.org. pp. 46–51. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ISBN 978-0231132909.

- ^ Roger DuPasquier. Unveiling Islam. Islamic Texts Society, 1992, p. 104

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam. Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 115.

- ^ Maududi (1967), Introduction of Ad-Dahr, "Period of revelation", p. 159.

- OCLC 9195533.

- ISBN 978-0199577576.

- ISBN 978-3-525-30099-2.

- ^ Hohrath, Daniel (1999). 'In Cartellen wird der Werth eines Gefangenen bestimmet', in In der Hand des Feindes: Kriegsgefangenschaft von der Antike bis zum zweiten Weltkrieg.

- ^ "Prisoner of war", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Historic England. "Site of the Norman Cross Depot for Prisoners of War (1006782)". National Heritage List for England. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023.

- ^ Rochlitz (1822). "Collected Works vol 6" (in German). p. 305ff. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019 – via Munich Digitization Center.

- ^ "Die Aufzeichnungen des Totengräbers Ahlemann 1813". leipzig-lese.de (in German). Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ISBN 978-0817317836.

- ^ "Myth: General Ulysses S. Grant stopped the prisoner exchange, and is thus responsible for all of the suffering in Civil War prisons on both sides – Andersonville National Historic Site". U.S. National Park Service). 18 July 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Richard Wightman Fox (7 January 2008). "National Life After Death". Slate. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ "Andersonville: Prisoner of War Camp-Reading 1". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ Hall, Yancey (1 July 2003). "US Civil War Prison Camps Claimed Thousands". National Geographic News.

- ^ "Geneva Convention". Peace Pledge Union. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "Story of an idea- the Film". International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Penrose, Mary Margaret. "War Crime". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (19 February 1991). "War in the Gulf: P.O.W.'s; U.S. Says Prisoners Seem War-Weary". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Mark (17 May 2012). "Pentagon: We Don't Call Them POWs Anymore". Time. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ "Department of Defense Instruction January 8, 2008 Incorporating Change 1, August 14, 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Years later Several ex POWS identified themselves (Ref: AMerican Legion Monthly Magazine September 1927)

- ^ Geo G. Phillimore and Hugh H. L. Bellot, "Treatment of Prisoners of War", Transactions of the Grotius Society, Vol. 5, (1919), pp. 47–64.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War. (1999) pp. 368–69 for data.

- ISBN 0-7864-3744-8

- ^ "375,000 Austrians Have Died in Siberia; Remaining 125,000 War Prisoner...—Article Preview—The". New York Times. 8 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Richard B. Speed, III. Prisoners, Diplomats and the Great War: A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity. (1990)

- ^ Ferguson, The Pity of War. (1999) Ch 13

- ^ Desmond Morton, Silent Battle: Canadian Prisoners of War in Germany, 1914–1919. 1992.

- ^ British National Archives, "The Mesopotamia campaign", at [1] Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ Peter Dennis, Jeffrey Grey, Ewan Morris, Robin Prior with Jean Bou, The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (2008) p. 429

- ^ H.S. Gullett, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–18, Vol. VII The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine (1941) pp. 620–622

- ^ The Postal History Society 1936–2011 – 75th anniversary display to the Royal Philatelic Society, London Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, p. 11

- ^ "The Queen and technology". Royal.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Search results – Resource centre". International Committee of the Red Cross. 3 October 2013.

- S2CID 159610355, p. 186

- ^ Lowe, Keith (2012), Savage Continent: Europe in the aftermath of World War II, p. 122

- ^ "World War II – prisoners of war POWs Japan". Archived from the original on 5 April 2023.

- ^ "International Humanitarian Law – State Parties / Signatories". Icrc.org. 27 July 1929. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Akira Fujiwara, Nitchû Sensô ni Okeru Horyo Gyakusatsu, Kikan Sensô Sekinin Kenkyû 9, 1995, p. 22

- ^ McCarthy, Terry (12 August 1992). "Japanese troops ate flesh of enemies and civilians". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023.

- ^ "An excellent reference for Japan and the treatment of US Airmen Pows is Toru Fukubayashi, "Allied Aircraft and Airmen Lost over Japanese Mainland" 20 May 2007. (PDF File 20 pages)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-84415-647-4.

- ^ Tsuyoshi, Masuda. "Forgotten tragedy of Italian war detainees". nhk.or.jp. NHK World. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, 2001, p. 360

- ^ "World War II POWs remember efforts to strike against captors". The Times-Picayune. Associated Press. 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "title=Japanese Atrocities in the Philippines Archived 27 July 2003 at the Wayback Machine". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS)

- ISBN 0-688-14370-9

- ISBN 1-920769-12-9.

- ^ Daws (1994), p. 297

- ]

- ISBN 978-1473687912.

- ^ Home Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Captivememories.org.uk. Retrieved on 24 May 2014.

- ^ Richard Vinen, The Unfree French: Life under the Occupation (2006) pp. 183–214

- ^ "International Humanitarian Law – State Parties / Signatories". Cicr.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Pride and Peril: Jewish American POWs in Europe". The National WWII Museum. 26 May 2021. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Ben Aharon Yitzhak". Jafi.org.il. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ See, for example, Joseph Robert White, 2006, "Flint Whitlock. Given Up for Dead: American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga" Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine (book review)

- ^ Inskeep, Steve (30 May 2005). "'Soldiers and Slaves' Details Saga of Jewish POWs". NPR. p. 1. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ See: Royal Canadian Air Force Association, "Allied Officers Deported to Buchenwald" and National Museum of the USAF, "Allied Victims of the Holocaust".

- ^ Ambrose, pp 360[full citation needed]

- ^ "Death March from Stalag Luft 4 during WWII". www.b24.net. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Guests of the Third Reich". guestsofthethirdreich.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Le porte della Memoria". Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Daniel Goldhagen, Hitler's Willing Executioners (p. 290)—"2.8 million young, healthy Soviet POWs" killed by the Germans, "mainly by starvation ... in less than eight months" of 1941–42, before "the decimation of Soviet POWs ... was stopped" and the Germans "began to use them as laborers".

- Historynet.com. Archived from the originalon 30 March 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-330-35212-3.

- ^ "Report at the session of the Russian association of WWII historians in 1998". Gpw.tellur.ru. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-8090-9325-0.

- ^ "Part VIII: Execution of the convention #Section I: General provisions". Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ISBN 0-14-100131-3p. 60

- ^ James D. Morrow, Order within Anarchy: The Laws of War as an International Institution, 2014, p. 218

- ^ a b c d Duțu, Alesandru (25 November 2015). "Prizonieri de război sovietici în România (1941–1944)" (in Romanian).

- ^ a b c Duțu, Alesandru (2 August 2015). "1943 – 1944. Prizonieri de război americani și englezi în România" (in Romanian).

- ^ Armă, Alexandru. "Prizonierii americani în "colivia de aur" de la Timișu de Jos" (in Romanian). Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Operatiunea Reunion (I)". iar80flyagain.org (in Romanian). 28 October 2022.

- ^ "No. 40 Squadron Wellington X ME990 -R F/O. Lawrence Franklin Tichborne". aircrewremembered.com. October 2018.

- ^ Rees, Simon. "German POWs and the Art of Survival". Historynet.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "German POWs in Allied Hands – World War II". Worldwar2database.com. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Benjamin Fischer (historian), "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999–2000.

- ^ Michael Hope. "Polish deportees in the Soviet Union". Wajszczuk.v.pl. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ^ "シベリア抑留、露に76万人分の資料 軍事公文書館でカード発見". Sankeishinbun. 24 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ a b Japanese POW group says files on over 500,000 held in Moscow Archived 24 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 7 March 1998

- ^ Commission on Human Rights, 56th session, 13 April 2000.

- ISBN 5-88439-093-9

- )

- ^ Paul M. Cole (1994) POW/MIA Issues: Volume 2, World War II and the Early Cold War Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine National Defense Research Institute. RAND Corporation, p. 28 Retrieved 18 July 2012

- ^ Tremblay, Robert, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, et al. "Histoires oubliées – Interprogrammes : Des prisonniers spéciaux" Interlude. Aired: 20 July 2008, 14h47 to 15h00. Note: See also Saint Helen's Island.

- ISBN 978-0-19-280670-3.

- Journal of American History, Vol. 94, No. 4. March 2008 Archived 14 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Philpot, Robert. "How Britain's German-born Jewish 'secret listeners' helped win World War II". www.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b George G. Lewis; John Mehwa (1982). "History of Prisoner of War Utilization by the United States Army 1776–1945" (PDF). Center of Military History, United States Army. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Ike's Revenge?". Time. 2 October 1989. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ S. P. MacKenzie "The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II" The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 66, No. 3. (September 1994), pp. 487–520.

- ^ Footnote to: K. W. Bohme, Zur Geschichte der deutschen Kriegsgefangenen des Zweiten Weltkrieges, 15 vols. (Munich, 1962–74), 1, pt. 1:x. (n. 1 above), 13:173; ICRC (n. 12 above), p. 334.

- ^ Renate Held, "Die deutschen Kriegsgefangenen in britischer Hand – ein Überblick [The German Prisoners of War in British Hands – An Overview] (in German)" (2008)

- ^ Eugene Davidsson, "The Trial of the Germans: An Account of the Twenty-Two Defendants Before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg", (1997) pp. 518–519 "the Allies stated in 1943 their intention of using forced workers outside Germany after the war, and not only did they express the intention but they carried it out. Not only Russia made use of such labour. France was given hundreds of thousands of German prisoners of war captured by the Americans, and their physical condition became so bad that the American Army authorities themselves protested. In England and the United States, too, some German prisoners of war were being put to work long after the surrender, and in Russia thousands of them worked until the mid-50s."

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7146-5657-1. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

Views in the Media were mirrored in the House of commons, where the arguments were characterized by a series of questions, the substance of which were always the same. Here too the talk was often of slave labour, and this debate was not laid to rest until the government announced its strategy.

- ^ Cobain, Ian (12 November 2005). "The secrets of the London Cage". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ a b Staff. ICRC in WW II: German prisoners of war in Allied hands Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 2 February 2005

- ^ "Ex-Death Camp Tells Story of Nazi and Soviet Horrors" New York Times, 17 December 2001

- ^ Butler, Desmond (17 December 2001). "Ex-Death Camp Tells Story of Nazi and Soviet Horrors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Butler, Desmond (17 December 2001). "Ex-Death Camp Tells Story of Nazi and Soviet Horrors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023.

- ^ Edward N. Peterson, The American Occupation of Germany, pp. 42, 116, "Some hundreds of thousands who had fled to the Americans to avoid being taken prisoner by the Soviets were turned over in May to the Red Army in a gesture of friendship."

- ^ Niall Ferguson, "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat" War in History 2004 11 (2) 148–192 p. 189, (footnote, referenced to: Heinz Nawratil, Die deutschen Nachkriegsverluste unter Vertriebenen, Gefangenen und Verschleppter: mit einer übersicht über die europäischen Nachkriegsverluste (Munich and Berlin, 1988), pp. 36f.)

- ISBN 978-0-472-10380-5pp. 360, 361

- ^ "The Legacy of Nuremberg", PBS. Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tarczai, Bela. "Hungarian Prisoners-of-War In French Captivity 1945–1947" (PDF). www.hungarianhistory.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2005.

- ^ Thorpe, Nick. Hungarian POW identified Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 17 September 2000. Accessed 11 December 2016

- OCLC 49784806.

- ^ Battle of Saipan Archived 3 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, historynet.com

- ^ American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs' Archived 19 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, "American and Australian soldiers massacred Japanese prisoners of war" according to The Faraway War by Prof Richard Aldrich of Nottingham University. From the diaries of Charles Lindberg: as told by a US officer, "Oh, we could take more if we wanted to", one of the officers replied. "But our boys don't like to take prisoners." "It doesn't encourage the rest to surrender when they hear of their buddies being marched out on the flying field and machine-guns turned loose on them." On Australian soldiers attitudes Eddie Stanton is quoted: "Japanese are still being shot all over the place", "The necessity for capturing them has ceased to worry anyone. Nippo soldiers are just so much machine-gun practice. Too many of our soldiers are tied up guarding them."

- ^ "Photos document brutality in Shanghai". CNN. 23 September 1996. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ CNN Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine 23 September 1996 image 2

- ^ CNN Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine 23 September 1996 image 3

- ISBN 978-8849523560

- ^ "Repatriation – The Dark Side of World War II". Fff.org. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Forced Repatriation to the Soviet Union: The Secret Betrayal". Hillsdale.edu. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Chinese operated three types of POW camps for Americans during the Korean War". April 1997. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ a b Adams, (2007), p. 62.

- ISBN 978-1-5584-9595-1, p.62

- ISBN 1-4259-5120-1

- ^ Thanh, Ngo Ba; Luce, Don. "In South Vietnamese Jails". Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Burns, Robert (29 August 1993). "Were Korean War POWs Sent to U.S.S.R? New Evidence Surfaces: Probe: Former Marine corporal spent 33 months as a prisoner and was interrogated by Soviet agents who thought he was a pilot". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023.

- ^ pp 26–33 Transfer of U.S. Korean War POWs To the Soviet Union. Nationalalliance.org. Retrieved on 24 May 2014. Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ USSR Archived 7 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Taskforceomegainc.org (17 September 1996). Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ "Falkland Islands: a gentleman's war". UPI. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022.

- PBS. Archived from the originalon 6 April 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Shaikh Azizur Rahman, "Two Chinese prisoners from '62 war repatriated Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine", The Washington Times.

- ^ Nazila Fathi (14 March 2003). "Threats and Responses: Briefly Noted; Iran-Iraq Prisoner Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Ukraine / Russia: Prisoners of war". OHCHR. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ISBN 0-304-35864-9

- ^ a b Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century, Greenhill Books, London, 1997, G. F. Krivosheev, editor (ref. Streit)

- ISBN 3-492-12056-3, p. 277

- ISBN 3-7694-0003-8, pp. 42–136, 254

- ^ "Kriegsgefangene: Viele kamen nicht zurück". Stern.de – Politik. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

Bibliography

- John Hickman, "What is a Prisoner of War For?" Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies. Vol. 36, No. 2. 2008. pp. 19–35.

- Full text of Third Geneva Convention, 1949 revision

- "Prisoner of War". Encyclopædia Britannica (CD ed.). 2002.

- Gendercide site

- "Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century", Greenhill Books, London, 1997, G. F. Krivosheev, editor.

- "Keine Kameraden. Die Wehrmacht und die sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941–1945", Dietz, Bonn 1997, ISBN 3-8012-5023-7

- Bligh, Alexander. 2015. "The 1973 War and the Formation of Israeli POW Policy – A Watershed Line? ". In Udi Lebel and Eyal Lewin (eds.), The 1973 Yom Kippur War and the Reshaping of Israeli Civil–Military Relations. Washington, DC: Lexington Books (2015), 121–146.

- Bligh, Alexander. 2014. "The development of Israel's POW policy: The 1967 War as a test case", Paper presented at the Seventh Annual ASMEA Conference: Searching for Balance in the Middle East and Africa (Washington, D.C., 31 October 2014).

Primary sources

- The stories of several American fighter pilots, shot down over North Vietnam are the focus of American Film Foundation's 1999 documentary Return with Honor, presented by Tom Hanks.

- Lewis H. Carlson, We We're Each Other's Prisoners: An Oral History of World War II American and German Prisoners of War, 1st ed.; 1997, BasicBooks (HarperCollins, Inc). ISBN 0-465-09120-2.

- Peter Dennis, Jeffrey Grey, Ewan Morris, Robin Prior with Jean Bou : The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History 2nd ed. (Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand, 2008) OCLC 489040963.

- H.S. Gullett, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–18, Vol. VII The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine 10th ed. (Sydney: Angus & Robinson, 1941) OCLC 220900153.

- Alfred James Passfield, The Escape Artist: An WW2 Australian prisoner's chronicle of life in German POW camps and his eight escape attempts, 1984 Artlook Books Western Australia. ISBN 0-86445-047-8.

- Rivett, Rohan D. (1946). Behind Bamboo. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Republished by Penguin, 1992; ISBN 0-14-014925-2.

- George G. Lewis and John Mewha, History of prisoner of war utilization by the United States Army, 1776–1945; Dept. of the Army, 1955.

- Vetter, Hal, Mutine at Koje Island; Charles Tuttle Company, Vermont, 1965.

- Jin, Ha, War Trash: A novel; Pantheon, 2004. ISBN 978-0-375-42276-8.

- Sean Longden, Hitler's British Slaves. First Published Arris Books, 2006. 2nd ed., Constable Robinson, 2007.

- Desflandres, Jean, Rennbahn: Trente-deux mois de captivité en Allemagne 1914–1917 Souvenirs d'un soldat belge, étudiant à l'université libre de Bruxelles 3rd edition (Paris, 1920)

Further reading

- Devaux, Roger. Treize Qu'ils Etaient[ISBN 2-916062-51-3

- Doylem Robert C. The Enemy in Our Hands: America's Treatment of Prisoners of War From the Revolution to the War on Terror (University Press of Kentucky, 2010); 468 pages; Sources include American soldiers' own narratives of their experiences guarding POWs plus Webcast Author Interview at the Pritzker Military Libraryon 26 June 2010

- Gascare, Pierre. Histoire de la captivité des Français en Allemagne (1939–1945), Éditions Gallimard, France, 1967. ISBN 2-07-022686-7.

- McGowran, Tom, Beyond the Bamboo Screen: Scottish Prisoners of War under the Japanese. 1999. Cualann Press Ltd[ISBN missing]

- ISBN 0-8128-8561-9.

- Krebs, Daniel, and Lorien Foote, eds. Useful Captives: The Role of POWs in American Military Conflicts (University Press of Kansas, 2021). [ISBN missing]

- Moore, Bob, & Kent Fedorowich eds., Prisoners of War and Their Captors in World War II, Berg Press, Oxford, UK, 1997. [ISBN missing]

- Bob Moore, and Kent Fedorowich. The British Empire and Its Italian Prisoners of War, 1940–1947 (2002) excerpt and text search

- David Rolf, Prisoners of the Reich, Germany's Captives, 1939–1945, 1998; on British POWs [ISBN missing]

- Scheipers, Sibylle Prisoners and Detainees in War , Institute of European History, 2011, retrieved: 16 November 2011.

- Paul J. Springer. America's Captives: Treatment of POWs From the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror (University Press of Kansas; 2010); 278 pages; Argues that the US military has failed to incorporate lessons on POW policy from each successive conflict. [ISBN missing]

- Vance, Jonathan F. (2006). The Encyclopedia of Prisoners of War & Internment (2nd ed.). Millerton, NY: Grey House Pub, 2006. p. 800. ISBN 978-1-59237-170-9

- Richard D. Wiggers, "The United States and the Denial of Prisoner of War (POW) Status at the End of the Second World War", Militargeschichtliche Mitteilungen 52 (1993) pp. 91–94.

- Winton, Andrew, Open Road to Faraway: Escapes from Nazi POW Camps 1941–1945. 2001. Cualann Press Ltd. [ISBN missing]

- Harris, Justin Michael. "American Soldiers and POW Killing in the European Theater of World War II"

- United States. Government Accountability Office. DOD's POW/MIA Mission: Capability and Capacity to Account for Missing Persons Undermined by Leadership Weaknesses and Fragmented Organizational Structure: Testimony before the Subcommittee on Military Personnel, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2013.

- On 12 February 2013, three American POWs gathered at the Pritzker Military Library for a webcast conversationregarding their individual experiences as POWs and the memoirs they each published:

- ISBN 978-0891414636

- ISBN 978-0615659053

- Donald E. Casey – To Fight for My Country, Sir!: Memoirs of a 19-year-old B-17 Navigator Shot Down in Nazi Germany 2009 ISBN 978-1448669875

External links

- Prisoners of war and humanitarian law, ICRC.

- Prisoners of War UK National Archives.

- Prisoners of War 1755–1831 UK National Archives ADM 103

- Archive of World War II memories BBC.

- Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II HistoryNet.

- Reports made by World War I prisoners of war UK National Archives

- First hand account of being a Japanese POW. Part 1 in a series of 4 video interviews Storyvault

- German POWs and the art of survival Historical Eye

- Current status of Vietnam War POW/MIA

- Clifford Reddish. War Memoirs of a British Army Signalman as a prisoner of the Japanese

- Canada's Forgotten PoW Camps CBC Digital Archives

- German army list of Stalags

- German army list of Oflags

- Colditz Oflag IVC POW Camp

- Lamsdorf Reunited

- New Zealand PoWs of Germany, Italy & Japan New Zealand Official History

- Notes of Japanese soldier in a USSR prison camp after World War II

- German prisoners of war in Allied hands (World War II) ICRC

- World War II U.S. POW Archives

- Korean War POW Archives

- Historic films about POWs in World War I European Film Gateway

- Jewish POW swapped by Germans in World War II