Fluoxetine

| |

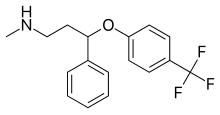

Fluoxetine (top), (R)-fluoxetine (left), (S)-fluoxetine (right) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /fluˈɒksətiːn/ floo-OKS-ə-teen |

| Trade names | Prozac, Sarafem, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a689006 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Addiction liability | None[1] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)[2] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–80%[2] |

| Protein binding | 94–95%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP2D6-mediated)[9] |

| Metabolites | Norfluoxetine, desmethylfluoxetine |

| Elimination half-life | 1–3 days (acute) 4–6 days (chronic)[9][10] |

| Excretion | Urine (80%), faeces (15%)[9][10] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 179 to 182 °C (354 to 360 °F) |

| Boiling point | 395 °C (743 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 14 |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Fluoxetine, sold under the brand name Prozac, among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class.[2] It is used for the treatment of major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[2] It is also approved for treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and children 8 years of age and over.[11] It has also been used to treat premature ejaculation.[2] Fluoxetine is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include indigestion, trouble sleeping, sexual dysfunction, loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, dry mouth, and rash. Serious side effects include

Fluoxetine was invented by

Medical uses

Fluoxetine is frequently used to treat

Depression

Fluoxetine is approved for the treatment of major depression in children and adults.[7] Meta-analysis of trials in adults conclude that fluoxetine modestly outperforms placebo.[35] Fluoxetine may be less effective than other antidepressants, but has high acceptability.[36]

For children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe depressive disorder, fluoxetine seems to be the best treatment (either with or without cognitive behavioural therapy, although fluoxetine alone does not appear to be superior to CBT alone) but more research is needed to be certain, as effect sizes are small and the existing evidence is of dubious quality.[37][38][39][40] A 2022 systematic review and trial restoration of the two original blinded-control trials used to approve the use of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression found that both of the trials were severely flawed, and therefore did not demonstrate the safety or efficacy of the medication.[41]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Fluoxetine is effective in the treatment of

Panic disorder

The efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of panic disorder was demonstrated in two 12-week randomized multicenter phase III clinical trials that enrolled patients diagnosed with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. In the first trial, 42% of subjects in the fluoxetine-treated arm were free of panic attacks at the end of the study, vs. 28% in the placebo arm. In the second trial, 62% of fluoxetine treated patients were free of panic attacks at the end of the study, vs. 44% in the placebo arm.[7]

Bulimia nervosa

A 2011 systematic review discussed seven trials which compared fluoxetine to a placebo in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, six of which found a statistically significant reduction in symptoms such as vomiting and binge eating.[46] However, no difference was observed between treatment arms when fluoxetine and psychotherapy were compared to psychotherapy alone.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Fluoxetine is used to treat

Impulsive aggression

Fluoxetine is considered a first-line medication for the treatment of impulsive aggression of low intensity.[52] Fluoxetine reduced low intensity aggressive behavior in patients in intermittent aggressive disorder and borderline personality disorder.[52][53][54] Fluoxetine also reduced acts of domestic violence in alcoholics with a history of such behavior.[55]

Obesity and overweight adults

In 2019 a

Special populations

In children and adolescents, fluoxetine is the antidepressant of choice due to tentative evidence favoring its efficacy and tolerability.[57][58] Evidence supporting an increased risk of major fetal malformations resulting from fluoxetine exposure is limited, although the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) of the United Kingdom has warned prescribers and patients of the potential for fluoxetine exposure in the first trimester (during organogenesis, formation of the fetal organs) to cause a slight increase in the risk of congenital cardiac malformations in the newborn.[59][60][61] Furthermore, an association between fluoxetine use during the first trimester and an increased risk of minor fetal malformations was observed in one study.[60]

However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies – published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada – concluded, "the apparent increased risk of fetal cardiac malformations associated with maternal use of fluoxetine has recently been shown also in depressed women who deferred SSRI therapy in pregnancy, and therefore most probably reflects an ascertainment bias. Overall, women who are treated with fluoxetine during the first trimester of pregnancy do not appear to have an increased risk of major fetal malformations."[62]

Per the FDA, infants exposed to SSRIs in late pregnancy may have an increased risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Limited data support this risk, but the FDA recommends physicians consider tapering SSRIs such as fluoxetine during the third trimester.[7] A 2009 review recommended against fluoxetine as a first-line SSRI during lactation, stating, "Fluoxetine should be viewed as a less-preferred SSRI for breastfeeding mothers, particularly with newborn infants, and in those mothers who consumed fluoxetine during gestation."[63] Sertraline is often the preferred SSRI during pregnancy due to the relatively minimal fetal exposure observed and its safety profile while breastfeeding.[64]

Adverse effects

Side effects observed in fluoxetine-treated persons in clinical trials with an incidence >5% and at least twice as common in fluoxetine-treated persons compared to those who received a placebo pill include abnormal dreams, abnormal

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction, including loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, lack of vaginal lubrication, and anorgasmia, are some of the most commonly encountered adverse effects of treatment with fluoxetine and other SSRIs. While early clinical trials suggested a relatively low rate of sexual dysfunction, more recent studies in which the investigator actively inquires about sexual problems suggest that the incidence is >70%.[67]

In 2019, the

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome

Fluoxetine's longer half-life makes it less common to develop antidepressant discontinuation syndrome following cessation of therapy, especially when compared with antidepressants with shorter half-lives such as paroxetine.[70][71] Although gradual dose reductions are recommended with antidepressants with shorter half-lives, tapering may not be necessary with fluoxetine.[72]

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including fluoxetine) is associated with shorter average duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points).[73][74] There is 30–36% increase in congenital heart defects among children whose mothers were prescribed fluoxetine during pregnancy,[12][13] with fluoxetine use in the first trimester associated with 38–65% increase in septal heart defects.[75][12]

Suicide

This section needs to be updated. (March 2022) |

In October 2004, the FDA added a black box warning to all antidepressant drugs regarding use in children.[76] In 2006, the FDA included adults aged 25 or younger.[77] Statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts found a 2-fold increase of the suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and 1.5-fold increase of suicidality in the 18–24 age group. The suicidality was slightly decreased for those older than 24, and statistically significantly lower in the 65 and older group.[78][79][80] This analysis was criticized by Donald Klein, who noted that suicidality, that is suicidal ideation and behavior, is not necessarily a good surrogate marker for suicide, and it is still possible, while unproven, that antidepressants may prevent actual suicide while increasing suicidality.[81] In February 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered an update to the warnings based on statistical evidence from twenty four trials in which the risk of such events increased from two percent to four percent relative to the placebo trials.[82]

On 14 September 1989, Joseph T. Wesbecker killed eight people and injured twelve before committing suicide.[83] His relatives and victims blamed his actions on the Prozac medication he had begun taking a month prior. The incident set off a chain of lawsuits and public outcries.[84] Lawyers began using Prozac to justify the abnormal behaviors of their clients.[85] Eli Lilly was accused of not doing enough to warn patients and doctors about the adverse effects, which it had described as "activation", years prior to the incident.[86]

There is less data on fluoxetine than on antidepressants as a whole. In 2004, the FDA had to combine the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications to obtain

QT prolongation

Fluoxetine can affect the

Overdose

In overdose, most frequent adverse effects include:[94]

|

Nervous system effects

|

Gastrointestinal effects

|

Other effects

|

Interactions

Contraindications include prior treatment (within the past 5–6 weeks, depending on the dose)

In case of short term administration of codeine for pain management, it is advised to monitor and adjust dosage. Codeine might not provide sufficient analgesia when fluoxetine is co-administered.[97] If opioid treatment is required, oxycodone use should be monitored since oxycodone is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system and fluoxetine and paroxetine are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 enzymes.[98] This means combinations of codeine or oxycodone with fluoxetine antidepressant may lead to reduced analgesia.[99]

In some cases, use of

Patients who are taking NSAIDs, antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and garlic supplements must be careful when taking fluoxetine or other SSRIs, as they can sometimes increase the blood-thinning effects of these medications.[101][102]

Fluoxetine and

Its use should also be avoided in those receiving other serotonergic drugs such as

Fluoxetine may also increase the risk of opioid overdose in some instances, in part due to its inhibitory effect on cytochrome P-450.

There is also the potential for interaction with highly protein-bound drugs due to the potential for fluoxetine to displace said drugs from the plasma or vice versa hence increasing serum concentrations of either fluoxetine or the offending agent.[9]

Pharmacology

| Molecular Target |

Fluoxetine | Norfluoxetine

|

|---|---|---|

| SERT | 1 | 19 |

| NET | 660 | 2700 |

| DAT | 4180 | 420 |

| 5-HT2A | 119 ± 10 | 300 |

| 5-HT2B | 2514 | 5100 |

| 5-HT2C | 118 ± 11 | 91.2 |

| α1 | 3000 | 3900 |

| M1 | 870 | 1200 |

| M2 | 2700 | 4600 |

| M3 | 1000 | 760 |

| M4 | 2900 | 2600 |

| M5 | 2700 | 2200 |

| H1 | 3250 | 10000 |

| Entries with this color indicate a lower bound of the Ki value. | ||

Pharmacodynamics

Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and does not appreciably inhibit norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake at therapeutic doses. It does, however, delay the reuptake of serotonin, resulting in serotonin persisting longer when it is released. Large doses in rats have been shown to induce a significant increase in synaptic norepinephrine and dopamine.[112][113][114][115] Thus, dopamine and norepinephrine may contribute to the antidepressant action of fluoxetine in humans at supratherapeutic doses (60–80 mg).[114][116] This effect may be mediated by 5HT2C receptors, which are inhibited by higher concentrations of fluoxetine.[117]

Fluoxetine increases the concentration of circulating

In addition, fluoxetine has been found to act as an

Fluoxetine has been shown to inhibit acid sphingomyelinase, a key regulator of ceramide levels which derives ceramide from sphingomyelin.[124][125]

Mechanism of action

While it is unclear how fluoxetine exerts its effect on mood, it has been suggested that fluoxetine elicits antidepressant effect by inhibiting serotonin reuptake in the synapse by binding to the reuptake pump on the neuronal membrane[126] to increase serotonin availability and enhance neurotransmission.[127] Over time, this leads to a downregulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which is associated with an improvement in passive stress tolerance, and delayed downstream increase in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which may contribute to a reduction in negative affective biases.[128][129] Norfluoxetine and desmethylfluoxetine are metabolites of fluoxetine and also act as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, increasing the duration of action of the drug.[130][126]

Prolonged exposure to fluoxetine changes the expression of genes involved in myelination, a process that shapes brain connectivity and contributes to symptoms of psychiatric disorders. The regulation of genes involved with myelination is partially responsible for the long-term therapeutic benefits of chronic SSRI exposure.[131]

Pharmacokinetics

The

The extremely slow elimination of fluoxetine and its active metabolite norfluoxetine from the body distinguishes it from other antidepressants. With time, fluoxetine and norfluoxetine inhibit their own metabolism, so fluoxetine

Measurement in body fluids

Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine may be quantitated in blood, plasma or serum to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized person or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma fluoxetine concentrations are usually in a range of 50–500 μg/L in persons taking the drug for its antidepressant effects, 900–3000 μg/L in survivors of acute overdosage and 1000–7000 μg/L in victims of fatal overdosage. Norfluoxetine concentrations are approximately equal to those of the parent drug during chronic therapy, but may be substantially less following acute overdosage, since it requires at least 1–2 weeks for the metabolite to achieve equilibrium.[141][142][143]

History

The work which eventually led to the discovery of fluoxetine began at

Fluoxetine appeared on the Belgian market in 1986.[149] In the U.S., the FDA gave its final approval in December 1987,[150] and a month later Eli Lilly began marketing Prozac; annual sales in the U.S. reached $350 million within a year.[148] Worldwide sales eventually reached a peak of $2.6 billion a year.[151]

Lilly tried several product line extension strategies, including extended release formulations and paying for clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and rebranding fluoxetine for that indication as "Sarafem" after it was approved by the FDA in 2000, following the recommendation of an advisory committee in 1999.[152][153][154] The invention of using fluoxetine to treat PMDD was made by Richard Wurtman at MIT; the patent was licensed to his startup, Interneuron, which in turn sold it to Lilly.[155]

To defend its Prozac revenue from generic competition, Lilly also fought a five-year, multimillion-dollar battle in court with the generic company Barr Pharmaceuticals to protect its patents on fluoxetine, and lost the cases for its line-extension patents, other than those for Sarafem, opening fluoxetine to generic manufacturers starting in 2001.[156] When Lilly's patent expired in August 2001,[157] generic drug competition decreased Lilly's sales of fluoxetine by 70% within two months.[152]

In 2000 an investment bank had projected that annual sales of Sarafem could reach $250M/year.[158] Sales of Sarafem reached about $85M/year in 2002, and in that year Lilly sold its assets connected with the drug for $295M to Galen Holdings, a small Irish pharmaceutical company specializing in dermatology and women's health that had a sales force tasked to gynecologists' offices; analysts found the deal sensible since the annual sales of Sarafem made a material financial difference to Galen, but not to Lilly.[159][160]

Bringing Sarafem to market harmed Lilly's reputation in some quarters. The diagnostic category of PMDD was

Society and culture

Prescription trends

In 2010, over 24.4 million prescriptions for generic fluoxetine were filled in the United States,[163] making it the third-most prescribed antidepressant after sertraline and citalopram.[163]

In 2011, 6 million prescriptions for fluoxetine were filled in the United Kingdom.[164] Between 1998 and 2017, along with amitriptyline, it was the most commonly prescribed first antidepressant for adolescents aged 12–17 years in England.[165]

Environmental effects

Fluoxetine has been detected in aquatic ecosystems, especially in North America.[166] There is a growing body of research addressing the effects of fluoxetine (among other SSRIs) exposure on non-target aquatic species.[167][168][169][170]

In 2003, one of the first studies addressed in detail the potential effects of fluoxetine on aquatic wildlife; this research concluded that exposure at environmental concentrations was of little risk to

Fluoxetine – similar to several other SSRIs – induces

Since 2003, a number of studies have reported fluoxetine-induced impacts on a number of behavioural and physiological endpoints, inducing antipredator behaviour,

Several common plants are known to absorb fluoxetine.

Politics

During the 1990 campaign for

American aircraft pilots

Beginning in April 2010, fluoxetine became one of four antidepressant drugs that the

Sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram are the only antidepressants permitted for

Research

The antibacterial effect in described above (

Fluoxetine has an

Veterinary use

Fluoxetine is commonly used and effective in treating anxiety related behaviours and separation anxiety in dogs, especially when given as supplementation to behaviour modification.[189][190]

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-8247-4497-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Mental health". Health Canada. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Prozac- fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Sarafem (fluoxetine hydrochloride tablets ) for oral use Initial U.S. Approval: 1987". DailyMed. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Prozac Fluoxetine Hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Eli Lilly Australia Pty. Limited. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ S2CID 1406955.

- ^ "Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents – Pediatrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ PMID 30415641.

- ^ S2CID 229357583.

- ^ "Fluoxetine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Fluoxetine – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Symbyax- olanzapine and fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "FDA Approves Symbyax as First Medication for Treatment-Resistant Depression" (Press release). Eli Lilly. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer207 (inactive 11 March 2024). Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2024.)

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link - ISBN 978-0-19-512314-2.

Dech and Budow (1991) were among the first to report the anecdotal use of fluoxetine in a case of PWS to control behavior problems, appetite, and trichotillomania.

- ^ Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DrugPoint® System (Internet) [cited 2013 Oct 4]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ^ Australian Medicines Handbook 2013. The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust; 2013.

- ^ British National Formulary (BNF) 65. Pharmaceutical Pr; 2013.

- PMID 16860338.

- ^ "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "NIMH•Eating Disorders". The National Institute of Mental Health. National Institute of Health. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "Treating social anxiety disorder". Harvard Health Publishing. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- PMID 23959778.

- S2CID 24674542.

- S2CID 32144885.

- S2CID 19614718.

- PMID 35409171.

- PMID 29477251.

- PMID 24353997.

- S2CID 242952585.

- PMID 32563306.

- ^ PMID 32982805.

- PMID 34029378.

- S2CID 250241461.

- PMID 11488259.

- S2CID 253347210.

- PMID 34002501.

- PMID 22176943.

- (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2014.

- PMID 24161307.

- S2CID 37088388.

- PMID 10363729.

- S2CID 9455962.

- S2CID 753100.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-119-15932-2.

- PMID 19389333.

- PMID 9400343.

- PMID 20673556.

- ^ PMID 31613390.

- S2CID 18186328.

- S2CID 1112192.

- PMID 16263070.

- ^ a b c Brayfield A, ed. (13 August 2013). "Fluoxetine Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 24 November 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ "Fluoxetine in pregnancy: slight risk of heart defects in unborn child" (PDF). MHRA. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 10 September 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- PMID 26334601.

- S2CID 29112093.

- ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- PMID 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-60913-713-7.

- PMID 24288712.

- ^ PRAC recommendations on signals: Adopted at the 13-16 May 2019 PRAC meeting (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 11 June 2019. p. 5. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- S2CID 231669986.

- PMID 28639936.

- PMID 16913164.

- PMID 28554948.

- PMID 23446732.

- S2CID 5558834.

- PMID 28513059.

- PMID 15995053.

- PMID 31130881.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ a b Stone MB, Jones ML (17 November 2006). "Clinical Review: Relationship Between Antidepressant Drugs and Suicidality in Adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). pp. 11–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ a b Levenson M, Holland C (17 November 2006). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). pp. 75–140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- S2CID 12599251.

- ^ "Suicidality in Children and Adolescents Being Treated With Antidepressant Medications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 November 2018.

- ^ Wolfson A. "Prozac maker paid millions to secure favorable verdict in mass shooting lawsuit, victims say". USA Today. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Prozac Litigation - Link to Suicide, Birth Defects & Class Action". Drugwatch.com. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Angier N (16 August 1990). "HEALTH; Eli Lilly Facing Million-Dollar Suits On Its Antidepressant Drug Prozac". The New York Times.

- ^ "Eli Lilly in storm over Prozac evidence". Financial Times. 30 December 2004. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Hammad TA (13 September 2004). "Results of the Analysis of Suicidality in Pediatric Trials of Newer Antidepressants" (PDF). Presentation at the Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Pediatric Advisory Committee on September 13, 2004. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. pp. 25, 28. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- PMID 19552869.

- ^ Committee on Safety of Medicines Expert Working Group (December 2004). "Report on The Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants" (PDF). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- PMID 15718537.

- PMID 26926294.

- PMID 27212965.

- PMID 23360890.

- ^ "Fluoxetine". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- PMID 10598311.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-7877-7.

A 2-week interval is adequate for all of these drugs, with the exception of fluoxetine. Because of the extended half-life of norfluoxetine, a minimum of 5 weeks should lapse between stopping fluoxetine (20mg/day) and starting an MAOI. With higher daily doses, the interval should be longer.

- PMID 28520350. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- S2CID 233579988.

- PMID 29955445.

- ^ "Dextromethorphan and fluoxetine Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Fluoxetine and ibuprofen Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ PMID 24569517.

- ISBN 978-1-60327-434-0.

- ^ S2CID 21838792. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 February 2019.

- ^ An extensive list of possible interactions is available in Lexi-Comp (September 2008). "Fluoxetine". The Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 3 September 2007.

- PMID 15784664.

- ^ a b "Combining certain opioids and commonly prescribed prescribed antidepressants may increase the risk of overdose". www.Popsci.com. 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- PMID 11876575.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- S2CID 11247427.

- S2CID 2679296.

- S2CID 27296534.

- ^ PMID 12464452.

- ^ PMID 19157982.

- S2CID 7485264.

- S2CID 24889381.

- S2CID 43499796.

- ^ S2CID 16061756.

- PMID 8831113.

- PMID 20021354.

- ^ "Fluoxetine". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "Calcium activated chloride channel". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. IUPHAR. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- S2CID 205391407.

- PMID 26605090.

- ^ a b "Fluoxetine". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- PMID 28858536.

- PMID 28153641.

- PMID 2878798.

- PMID 26393488.

- ^ a b "Prozac Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, Studies, Metabolism". RxList.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- PMID 16472103.

- PMID 10674711.

- ^ PMID 10917403.

- ^ "Drug Treatments in Psychiatry: Antidepressants". Newcastle University School of Neurology, Neurobiology and Psychiatry. 2005. Archived from the original on 17 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ S2CID 13542714.

- PMID 12063152.

- ^ PMID 15886723.

- S2CID 42816815.

- PMID 3871765.

- PMID 1741813.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 645–48.

- ^ a b "Ray W. Fuller, David T. Wong, and Bryan B. Molloy". Science History Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- PMID 7623609.

- ^ "Chemical & Engineering News: Top Pharmaceuticals: Prozac". pubsapp.acs.org. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ PMID 4549929.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-95606-6.

- ^ Swiatek J (2 August 2001). "Prozac's profitable run coming to an end for Lilly". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007.

- ^ "Electronic Orange Book". Food and Drug Administration. April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- ^ Simons J (28 June 2004). "Lilly Goes Off Prozac The drugmaker bounced back from the loss of its blockbuster, but the recovery had costs". Fortune Magazine.

- ^ a b Class S (2 December 2002). "Pharma Overview". Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Lilly Menstrual drug OK'd – Jul. 6, 2000". Money.cnn.com. 6 July 2000. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Mechatie E (1 December 1999). "FDA Panel Agrees Fluoxetine Effective For PMDD". International Medical News Group.

- ^ Herper H (25 September 2002). "A Biotech Phoenix Could Be Rising". Forbes.

- ^ Petersen M (2 August 2001). "Drug Maker Is Set to Ship Generic Prozac". The New York Times.

- ^ "Patent Expiration Dates for Common Brand-Name Drugs". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Village Voice. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Galen to Pay $295 Million For U.S. Rights to Lilly Drug". Dow Jones Newswires in The Wall Street Journal. 9 December 2002.

- ^ Murray-West R (10 December 2002). "Galen takes Lilly's reinvented Prozac". Telegraph.

- ^ Petersen M (29 May 2002). "New Medicines Seldom Contain Anything New, Study Finds". The New York Times.

- ^ Vedantam S (29 April 2001). "Renamed Prozac Fuels Women's Health Debate". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "Top 200 Generic Drugs by Units in 2010" (PDF). Drug Topics: Voice of the Pharmacist. June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2012.

- ^ Macnair P (September 2012). "BBC – Health: Prozac". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012.

In 2011 over 43 million prescriptions for antidepressants were handed out in the UK and about 14 per cent (or nearly 6 million prescriptions) of these were for a drug called fluoxetine, better known as Prozac.

- PMID 32697803.

- PMID 23227929.

- PMID 25245382.

- ^ PMID 24411166.

- ^ PMID 12691711.

- S2CID 43341257.

- ISSN 0097-6156.

- PMID 28063712.

- S2CID 85340761.

- S2CID 25189716. Archived from the original(PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- PMID 20864192.

- PMID 21536011.

- PMID 20692053.

- PMID 18547660.

- ^ a b

- Richmond EK, Rosi EJ, Reisinger AJ, Hanrahan BR, Thompson RM, Grace MR (1 January 2019). "Influences of the antidepressant fluoxetine on stream ecosystem function and aquatic insect emergence at environmentally realistic concentrations". Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 34 (1): 513–531. S2CID 246673478.

- Richmond EK, Rosi EJ, Reisinger AJ, Hanrahan BR, Thompson RM, Grace MR (1 January 2019). "Influences of the antidepressant fluoxetine on stream ecosystem function and aquatic insect emergence at environmentally realistic concentrations". Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 34 (1): 513–531.

- ^ a b c d e

- Qin Q, Chen X, Zhuang J (9 September 2014). "The Fate and Impact of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Agricultural Soils Irrigated With Reclaimed Water". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (13): 1379–1408. S2CID 20021866.

- Qin Q, Chen X, Zhuang J (9 September 2014). "The Fate and Impact of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Agricultural Soils Irrigated With Reclaimed Water". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (13): 1379–1408.

- ^ S2CID 231746862.

- ^ MacPherson M (2 September 1990). "Prozac, Prejudice and the Politics of Depression". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Duquette A, Dorr L (2 April 2010). "FAA Proposes New Policy on Antidepressants for Pilots" (Press release). Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Office of Aerospace Medicine, Federal Aviation Administration (2 December 2016). "Decision Considerations – Aerospace Medical Dispositions: Item 47. Psychiatric Conditions – Use of Antidepressant Medications". Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners. Washington, DC: United States Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017.

- ^ "Mental Health GM - Centrally Acting Medication". Civil Aviation Authority. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Class 1/2 Certification – Depression" (PDF). Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b

- • McCammon JM, S2CID 11962425. NIHMSID: NIHMS368312.

- • McCammon JM,

- ^ a b

- • Mangoni AA, Tuccinardi T, Collina S, Vanden Eynde JJ, Muñoz-Torrero D, Karaman R, et al. (June 2018). "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3". S2CID 205636792.

- • Mangoni AA, Tuccinardi T, Collina S, Vanden Eynde JJ, Muñoz-Torrero D, Karaman R, et al. (June 2018). "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3".

- S2CID 253873416.

- PMID 33062616.

Further reading

- Shorter E (2014). "The 25th anniversary of the launch of Prozac gives pause for thought: where did we go wrong?". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 204 (5): 331–2. PMID 24785765.

- Haberman C (21 September 2014). "Selling Prozac as the Life-Enhancing Cure for Mental Woes". The New York Times.