Psychedelic drug

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary mental states (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips") and an apparent expansion of consciousness.[2][3] Also referred to as classic hallucinogens or serotonergic hallucinogens, the term psychedelic is sometimes used more broadly to include various types of hallucinogens, such as those which are atypical or adjacent to psychedelia like salvia and MDMA, respectively.[4]

Classic psychedelics generally cause specific psychological, visual, and auditory changes, and oftentimes a substantially

Most psychedelic drugs fall into one of the three families of chemical compounds:

Many psychedelic drugs are illegal worldwide under the

Etymology and nomenclature

The term

Aldous Huxley had suggested his own coinage phanerothyme (Greek phaneroein- "to make manifest or visible" and Greek thymos "soul", thus "to reveal the soul") to Osmond in 1956.[29] Recently, the term entheogen (meaning "that which produces the divine within") has come into use to denote the use of psychedelic drugs, as well as various other types of psychoactive substances, in a religious, spiritual, and mystical context.[30]

In 2004, David E. Nichols wrote the following about the nomenclature used for psychedelic drugs:[30]

Many different names have been proposed over the years for this drug class. The famous German toxicologist Louis Lewin used the name phantastica earlier in this century, and as we shall see later, such a descriptor is not so farfetched. The most popular names—hallucinogen, psychotomimetic, and psychedelic ("mind manifesting")—have often been used interchangeably. Hallucinogen is now, however, the most common designation in the scientific literature, although it is an inaccurate descriptor of the actual effects of these drugs. In the lay press, the term psychedelic is still the most popular and has held sway for nearly four decades. Most recently, there has been a movement in nonscientific circles to recognize the ability of these substances to provoke mystical experiences and evoke feelings of spiritual significance. Thus, the term entheogen, derived from the Greek word entheos, which means "god within", was introduced by Ruck et al. and has seen increasing use. This term suggests that these substances reveal or allow a connection to the "divine within". Although it seems unlikely that this name will ever be accepted in formal scientific circles, its use has dramatically increased in the popular media and on internet sites. Indeed, in much of the counterculture that uses these substances, entheogen has replaced psychedelic as the name of choice and we may expect to see this trend continue.

Robin Carhart-Harris and Guy Goodwin write that the term psychedelic is preferable to hallucinogen for describing classical psychedelics because of the term hallucinogen's "arguably misleading emphasis on these compounds' hallucinogenic properties."[31]

While the term psychedelic is most commonly used to refer only to serotonergic hallucinogens,[11][10][32][33] it is sometimes used for a much broader range of drugs, including empathogen–entactogens, dissociatives, and atypical hallucinogens/psychoactives such as Amanita muscaria, Cannabis sativa, Nymphaea nouchali and Salvia divinorum.[22][34] Thus, the term serotonergic psychedelic is sometimes used for the narrower class.[35][36] It is important to check the definition of a given source.[30] This article uses the more common, narrower definition of psychedelic.

Examples

- 2C-B (2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine) is a substituted phenethylamine first synthesised in 1974 by Alexander Shulgin.[37][page needed] 2C-B is both a psychedelic and a mild entactogen, with its psychedelic effects increasing and its entactogenic effects decreasing with dosage. 2C-B is the most well known compound in the 2C family, their general structure being discovered as a result of modifying the structure of mescaline.[37][page needed]

- DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is an indole alkaloid found in various species of plants. Traditionally it is consumed by tribes in South America in the form of ayahuasca. A brew is used that consists of DMT-containing plants as well as plants containing MAOIs, specifically harmaline, which allows DMT to be consumed orally without being rendered inactive by monoamine oxidase enzymes in the digestive system.[38] In the Western world DMT is more commonly consumed via the vaporisation of freebase DMT. Whereas Ayahuasca typically lasts for several hours, inhalation has an onset measured in seconds and has effects measured in minutes, being significantly more intense.[39] Particularly in vaporised form, DMT has the ability to cause users to enter a hallucinatory realm fully detached from reality, being typically characterised by hyperbolic geometry, and described as defying visual or verbal description.[40] Users have also reported encountering and communicating with entitites within this hallucinatory state.[41] DMT is the archetypal substituted tryptamine, being the structural scaffold of psilocybin and – to a lesser extent – the lysergamides.

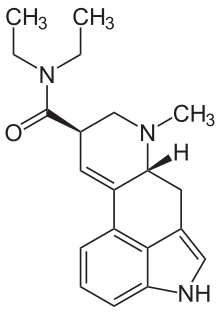

- LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) is a derivative of lysergic acid, which is obtained from the hydrolysis of ergotamine. Ergotamine is an alkaloid found in the fungus Claviceps purpurea, which primarily infects rye. LSD is both the prototypical psychedelic and the prototypical lysergamide. As a lysergamide, LSD contains both a tryptamine and phenethylamine group within its structure. As a result of containing a phenethylamine group LSD agonises dopamine receptors as well as serotonin receptors,[42] making it more energetic in effect in contrast to the more sedating effects of psilocin, which is not a dopamine agonist.[43]

- Echinopsis pachanoi). Mescaline has effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin, albeit with a greater emphasis on colors and patterns.[44][page needed] Ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.[45]

Uses

Traditional

A number of frequently mentioned or traditional psychedelics such as

Although people of

]Psychedelic therapy

Psychedelic therapy (or psychedelic-assisted therapy) is the proposed use of psychedelic drugs to treat mental disorders.[58] As of 2021, psychedelic drugs are controlled substances in most countries and psychedelic therapy is not legally available outside clinical trials, with some exceptions.[33][59]

The procedure for psychedelic therapy differs from that of therapies using conventional psychiatric medications. While conventional medications are usually taken without supervision at least once daily, in contemporary psychedelic therapy the drug is administered in a single session (or sometimes up to three sessions) in a therapeutic context.[60] The therapeutic team prepares the patient for the experience beforehand and helps them integrate insights from the drug experience afterwards.[61][62] After ingesting the drug, the patient normally wears eyeshades and listens to music to facilitate focus on the psychedelic experience, with the therapeutic team interrupting only to provide reassurance if adverse effects such as anxiety or disorientation arise.[61][62]

As of 2022, the body of high-quality evidence on psychedelic therapy remains relatively small and more, larger studies are needed to reliably show the effectiveness and safety of psychedelic therapy's various forms and applications.[21][22] On the basis of favorable early results, ongoing research is examining proposed psychedelic therapies for conditions including major depressive disorder,[21][63] and anxiety and depression linked to terminal illness.[21][64] The United States Food and Drug Administration has granted "breakthrough therapy" status, which expedites the assessment of promising drug therapies for potential approval,[note 1] to psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder.[33]

Recreational

Recreational use of psychedelics has been common since the psychedelic era of the mid 1960s, and continues to play a role in various festivals and events, including Burning Man.[16][17] A survey published in 2013 found that 13.4% of American adults had used a psychedelic.[66]

Microdosing

Psychedelic microdosing is the practice of using sub-threshold doses (

A 2022 study recognized signatures of psilocybin microdosing in natural language and concluded that low amount of psychedelics have potential for application, and ecological observation of microdosing schedules.[71][72]

Pharmacology

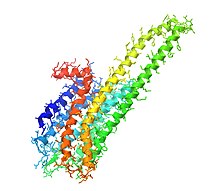

While the method of action of psychedelics is not fully understood, they are known to show affinities for various 5-HT (serotonin) receptors in different ways and levels, and may be classified by their activity at different 5-HT sub-types, particularly 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C.

Tryptamines

Phenethylamines

Lysergamides

Psychedelic experiences

Although several attempts have been made, starting in the 19th and 20th centuries, to define common

During a speech on his 100th birthday, the inventor of LSD, Albert Hofmann said of the drug: "It gave me an inner joy, an open mindedness, a gratefulness, open eyes and an internal sensitivity for the miracles of creation... I think that in human evolution it has never been as necessary to have this substance LSD. It is just a tool to turn us into what we are supposed to be."[92] With certain psychedelics and experiences, a user may also experience an "afterglow" of improved mood or perceived mental state for days or even weeks after ingestion in some cases.[93] In 1898, the English writer and intellectual Havelock Ellis reported a heightened perceptual sensitivity to "the more delicate phenomena of light and shade and color" for a prolonged period of time after his exposure to mescaline.[94] Good trips are reportedly deeply pleasurable, and typically involve intense joy or euphoria, a greater appreciation for life, reduced anxiety, a sense of spiritual enlightenment, and a sense of belonging or interconnectedness with the universe.[95][96] Negative experiences, colloquially known as "bad trips," evoke an array of dark emotions, such as irrational fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, dread, distrustfulness, hopelessness, and even suicidal ideation.[97] While it is impossible to predict when a bad trip will occur, one's mood, surroundings, sleep, hydration, social setting, and other factors can be controlled (colloquially referred to as "set and setting") to minimize the risk of a bad trip.[98][99] The concept of "set and setting" also generally appears to be more applicable to psychedelics than to other types of hallucinogens such as deliriants, hypnotics and dissociative anesthetics.[100]

Classic psychedelics are considered to be those found in nature like psilocybin, DMT, mescaline, and LSD which is derived from naturally occurring ergotamine, and non-classic psychedelics are considered to be newer analogs and derivatives of pharmacophore lysergamides, tryptamine, and phenethylamine structures like 2C-B. Many of these psychedelics cause remarkably similar effects, despite their different chemical structure. However, many users report that the three major families have subjectively different qualities in the "feel" of the experience, which are difficult to describe. Some compounds, such as 2C-B, have extremely tight "dose curves", meaning the difference in dose between a non-event and an overwhelming disconnection from reality can be very slight. There can also be very substantial differences between the drugs; for instance, 5-MeO-DMT rarely produces the visual effects typical of other psychedelics.[11]

Potential adverse effects

Despite the contrary perception of much of the public, psychedelic drugs are not addictive and are physiologically safe.[18][19][11] As of 2016, there have been no known deaths due to overdose of LSD, psilocybin, or mescaline.[11]

Risks do exist during an unsupervised psychedelic experience, however;

Psilocybin-induced states of mind share features with states experienced in psychosis, and while a causal relationship between psilocybin and the onset of psychosis has not been established as of 2011, researchers have called for investigation of the relationship.[102] Many of the persistent negative perceptions of psychological risks are unsupported by the currently available scientific evidence, with the majority of reported adverse effects not being observed in a regulated and/or medical context.[103] A population study on associations between psychedelic use and mental illness published in 2013 found no evidence that psychedelic use was associated with increased prevalence of any mental illness.[104]

Using psychedelics poses certain risks of re-experiencing of the drug's effects, including flashbacks and hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD).[102] These non-psychotic effects are poorly studied, but the permanent symptoms (also called "endless trip") are considered to be rare.[105]

Serotonin syndrome can be caused by combining psychedelics with other serotonergic drugs, including certain antidepressants, opioids, CNS stimulants (e.g. MDMA), 5-HT1 agonists (e.g. triptans), herbs and others.[106][107][108][109]

Potential therapeutic effects

Psychedelic substances which may have therapeutic uses include psilocybin, LSD, and mescaline.

It has long been known that psychedelics promote neurite growth and neuroplasticity and are potent psychoplastogens.[110][111][112] There is evidence that psychedelics induce molecular and cellular adaptations related to neuroplasticity and that these could potentially underlie therapeutic benefits.[113][114] Psychedelics have also been shown to have potent anti-inflammatory activity and therapeutic effects in animal models of inflammatory diseases including asthma,[115] and cardiovascular disease and diabetes.[116]

Surrounding culture

Psychedelic culture includes manifestations such as

Legal status

Many psychedelics are classified under Schedule I of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 as drugs with the greatest potential to cause harm and no acceptable medical uses.[123] In addition, many countries have analogue laws; for example, in the United States, the Federal Analogue Act of 1986 automatically forbids any drugs sharing similar chemical structures or chemical formulas to illicit or prohibited substances if sold for human consumption.[124]

U.S. states such as Oregon and Colorado have also instituted decriminalization and legalization measures of psychedelics[125] and states like New Hampshire are attempting to do the same.[126] J.D. Tuccille argues that increasing rates of use of psychedelics in defiance of the law are likely to result in more widespread legalization and decriminalization of the substances in the United States (as has happened with alcohol and cannabis).[127]

See also

- Aztec use of entheogens

- Bwiti

- Cognitive liberty

- Concord Prison Experiment

- Designer Drugs

- Dissociative drug

- Deliriant

- Drug harmfulness

- Entheogenic drugs and the archaeological record

- Entheogenics and the Maya

- Hallucinogenic fish

- Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals

- Hamilton's Pharmacopeia

- History of lysergic acid diethylamide

- Ibogaine

- List of designer drugs

- List of psychedelic drugs

- List of psychedelic plants

- Marsh Chapel Experiment

- Morning glory

- Mystical psychosis

- PiHKAL

- Psychedelia – Film about the history of psychedelic drugs

- Research chemical

- Serotonergic cell groups

- Serotonin syndrome

- Tabernanthe iboga

- TiHKAL

Categories

Notes

- ^ The Food and Drug Administration describes the designation of breakthrough therapy as "a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s)."[65]

References

- ^ "Peyote San Pedro Cactus – Shamanic Sacraments". D.M.Taylor.

- ^ PMID 10432484.

- ^ PMID 30245648.

- ^ S2CID 247521633. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ PMID 30174629.

- ^ S2CID 7845214.

- ^ McKenna, Terence (1992). Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution

- ^ W. Davis (1996), One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest. New York, Simon and Schuster, Inc. p. 120.

- ^ a b "Crystal Structure of LSD and 5-HT2AR Part 2: Binding Details and Future Psychedelic Research Paths". Psychedelic Science Review. 2020-10-05. Retrieved 2021-02-12.

- ^ PMID 28401524.

- ^ PMID 26841800.

- OCLC 123438340.

- S2CID 102487343.

- ^ PMID 30042848.

The connection with findings about PCC deactivation in 'effortless awareness' meditation is obvious, and bolstered by the finding that acute ayahuasca intoxication increases mindfulness-related capacities.

- PMID 22114193.

- ^ PMID 24627778.

- ^ PMID 27454674.

- ^ a b Le Dain G (1971). The Non-medical Use of Drugs: Interim Report of the Canadian Government's Commission of Inquiry. p. 106.

Physical dependence does not develop to LSD

- ^ PMID 17105338.

- ^ Rich Haridy (24 October 2018). "Psychedelic psilocybin therapy for depression granted Breakthrough Therapy status by FDA". newatlas.com. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ S2CID 245906937.

- ^ S2CID 211524704.

- ^ PMID 26350908.

- ^ Orth T (July 28, 2022). "One in four Americans say they've tried at least one psychedelic drug". YouGov.

- PMC 381240.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, September 2007, s.v., Etymology

- ^ A. Weil, W. Rosen. (1993), From Chocolate To Morphine: Everything You Need To Know About Mind-Altering Drugs. New York, Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 93

- ^ W. Davis (1996), "One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest". New York, Simon and Schuster, Inc. p. 120.

- ^ iia700700.us.archive.org

- ^ PMID 14761703.

- PMID 28443617.

- S2CID 227157734.

- ^ S2CID 238355863.

- S2CID 235242044.

- S2CID 226217912.

- S2CID 235796130.

- ^ OCLC 25627628.

- S2CID 6147566.

- PMID 16227062.

- PMID 8297217.

- PMID 32345112.

- PMID 1207384.

- S2CID 12656091.

- OCLC 489218895.

- ISSN 1050-8619.

- S2CID 7845214.

- ^ a b "4-HO-MiPT". Psychedelic Science Review. 2020-01-06. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- S2CID 239438352. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "History of Psychedelics: How the Mazatec Tribe Brought Entheogens to the World". Psychedelic Times. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- OCLC 1229544084.

- PMID 31250802.

- PMID 17090303.

- S2CID 252954052.

- ISBN 978-2-8218-4453-7. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-498-5. pp. 45–49.

- ^ "Declaran Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación a los conocimientos, saberes y usos del cactus San Pedro". elperuano.pe (in Spanish). 2022-11-17. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- ^ a b "Psychedelics Weren't As Common in Ancient Cultures As We Think". Vice Media. Vice. December 10, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ISSN 0028-3908.

- PMID 33827588.

- S2CID 214753833.

- ^ PMID 18593734.

- ^ S2CID 53291327.

- S2CID 218873949.

- S2CID 244490236.

- ^ "Breakthrough Therapy". United States Food and Drug Administration. 1 April 2018. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- PMID 23976938.

- ^ Fadiman J (2016-01-01). "Microdose research: without approvals, control groups, double blinds, staff or funding". Psychedelic Press. XV.

- ^ Brodwin E (30 January 2017). "The truth about 'microdosing,' which involves taking tiny amounts of psychedelics like LSD". Business Insider. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ Dahl H (7 July 2015). "A Brief History of LSD in the Twenty-First Century". Psychedelic Press UK. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- S2CID 149445841.

- ^ Chemistry Uo, Prague T. "Recognizing signatures of psilocybin microdosing in natural language". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- S2CID 247067976.

- ^ Dolan EW (2023-06-02). "Neuroscience research sheds light on how LSD alters the brain's "gatekeeper"". Psypost - Psychology News. Retrieved 2023-06-02.

- PMID 29898390.

- PMID 36795823.

- S2CID 2984583.

- S2CID 37564231.

- PMID 24944732.

- ^ "4-HO-MET". The Drug Classroom. Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- OCLC 38503252.

- PMID 21073468.

- ISSN 1754-2413.

- PMID 12505801.

- S2CID 212738912.

- PMID 32415750.

- PMID 28025814.

- PMID 29568270.

- S2CID 144948636.

- S2CID 12126296.

- PMID 6492831. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- PMID 26841800.

- ^ "LSD: The Geek's Wonder Drug?". Wired. 16 January 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- S2CID 16483172.

- ^ Hanson D (29 April 2013). "When the Trip Never Ends". Dana Foundation.

- ^ Honig D. "Frequently Asked Questions". Erowid. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016.

- PMID 6054248. Archived from the original(PDF) on April 30, 2011.

- ^ Canadian government (1996). "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". Justice Laws. Canadian Department of Justice. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Rogge T (May 21, 2014), Substance use – LSD, MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine, archived from the original on July 28, 2016, retrieved July 14, 2016

- ^ CESAR (29 October 2013), LSD, Center for Substance Abuse Research, University of Maryland, archived from the original on July 15, 2016, retrieved 14 July 2016

- PMID 27454674.

- PMID 29356590.

- ^ PMID 21256914.

- PMID 35107059.

- PMID 23976938.

- PMID 21035275.

- PMID 15635814.

Mechanisms of serotonergic drugs implicated in serotonin syndrome... Stimulation of serotonin receptors... LSD

- ^ "AMT". DrugWise.org.uk. 2016-01-03. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ Alpha-methyltryptamine (AMT) – Critical Review Report (PDF) (Report). World Health Organisation – Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (published 2014-06-20). 20 June 2014. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-18.

- PMID 19889983.

- S2CID 14178672.

- PMID 29898390.

- PMID 34566723.

- S2CID 252381170.

- PMID 25416380.

- PMID 31530895.

- ISBN 0-252-06915-3.

- S2CID 151517152.

- CiteSeerX 10.1.1.854.6673. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- S2CID 191583864.

- ^ St John, Graham. "Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival." Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture, 1(1) (2009).

- ^ Hirschfelder A (Jan 14, 2016). "The Trips Festival explained". Experiments in Environment: The Halprin Workshops, 1966–1971.

- S2CID 46510541.

- ^ "U.S.C. Title 21 – FOOD AND DRUGS". www.govinfo.gov. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Pot Prohibition Continues Collapsing, and Psychedelic Bans Could Be Next". November 9, 2022.

- ^ "New Hampshire Lawmakers File Psilocybin And Broader Drug Decriminalization Bills For 2022". December 29, 2021.

- ^ Tuccille J (3 August 2022). "Scofflaws Lead the Way To Legalizing Psychedelic Drugs". Reason. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

Further reading

- Echard W (2017). Psychedelic Popular Music: A History through Musical Topic Theory. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02645-3.

- Halberstadt AL, Franz X. Vollenweider, David E. Nichols, eds. (2018). Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs. Vol. 36. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-55878-2.

- Jay M (2019). Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. S2CID 241952235.

- Letheby C (2021). Philosophy of Psychedelics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884312-2.

- Richards WA (2016). Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54091-9.

- Siff S (2015). Acid Hype: American News Media and the Psychedelic Experience. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09723-2.

- Winstock, Ar; Timmerman, C; Davies, E; Maier, Lj; Zhuparris, A; Ferris, Ja; Barratt, Mj; Kuypers, Kpc (2021). Global Drug Survey (GDS) 2020 Psychedelics Key Findings Report.

External links

Psychedelic Timeline by Tom Frame, Psychedelic Times