Pulse pressure

| Pulse pressure | |

|---|---|

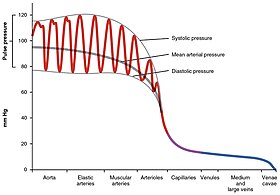

Pulse pressure variation (PPV) in different arteries and veins |

Pulse pressure is the difference between

Calculation

Pulse pressure is calculated as the difference between the systolic blood pressure and the diastolic blood pressure.[3][4]

The systemic pulse pressure is approximately proportional to

The aorta has the highest compliance in the arterial system due in part to a relatively greater proportion of elastin fibers versus smooth muscle and collagen. This serves to dampen the pulsatile (maximum pumping pressure) of the left ventricle, thereby reducing the initial systolic pulse pressure, but slightly raising the subsequent diastolic phase. If the aorta becomes rigid, stiff and inextensible because of disorders, such as arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis or elastin defects (in connective tissue diseases), the pulse pressure would be higher due to less compliance of the aorta.

- Systemic pulse pressure (usually measured at upper arm artery) = Psystolic − Pdiastolic

- e.g. normal 12 mmHg - 8 mmHg = 4 mmHg[3]

- low: 10 mmHg − 8 mmHg = 2 mmHg

- high: 16 mmHg − 8 mmHg = 8 mmHg

- Pulmonary pulse pressure is normally much lower than systemic blood pressure due to the higher compliance of the pulmonary system compared to the arterial circulation.catheterization or may be estimated by transthoracic echocardiography Normal pulmonary artery pressure is 8 mmHg–20 mmHg at rest.[7]

- e.g. normal: 1 mmHg − mmHg = mmHg

- high: 2 mmHg − 1 mmHg = 1 mmHg

Values and variation

Low (narrow) pulse pressure

A pulse pressure is considered abnormally low if it is less than 25% of the systolic value.

The most common cause of a low (narrow) pulse pressure is a drop in left ventricular stroke volume. In trauma, a low or narrow pulse pressure suggests significant blood loss.[8]

A narrow pulse pressure is also caused by aortic stenosis.[3] This is due to the decreased stroke volume in aortic stenosis.[9] Other conditions that can cause a narrow pulse pressure include blood loss (due to decreased blood volume), and cardiac tamponade (due to decreased filling time). In the majority of these conditions, systolic pressure decreases, while diastolic pressure remains normal, leading to a narrow pulse pressure.[9]

High (wide) pulse pressure

Consistently high

A pulse pressures of 50 mmHg or more can increase the risk of heart disease, heart rhythm disorders, stroke and other cardiovascular diseases and events. Higher pulse pressures are also thought to play a role in eye and kidney damage from diseases such as diabetes.[3] There are currently no drugs approved to lower pulse pressure, but some antihypertensive drugs have been shown to modestly lower pulse pressure, while other drugs used for hypertension can actually have the counterproductive side effect of increasing resting pulse pressure.[10]

In hypertensive patients, a high pulse pressure can often be an indicator of

Other conditions that can lead to a high pulse pressure include

A high pulse pressure combined with

Common causes of widening pulse pressure include:[3][medical citation needed]

- Anemia

- Aortic dissection

- Atherosclerosis[13]

- Arteriovenous fistula[13]

- Chronic aortic regurgitation

- Aortic root aneurysm[15]

- Aortic root dilation[15]

- Beri beri[13]

- Distributive shock[13]

- Endocarditis

- Fever

- Heart block

- Increased intracranial pressure[14][13]

- Patent ductus arteriosus

- Pregnancy

- Thyrotoxicosis[13]

- Pregnancy[13]

From exercise

For most individuals, during aerobic exercise, the systolic pressure progressively increases while the diastolic pressure remains about the same, thereby widening the pulse pressure. These pressure changes facilitate an increase in

Clinical significance

Pulse pressure has implications for both cardiovascular disease as well as many non-cardiovascular diseases. Even in people without other risk factors for cardiovascular disease, a consistently wide pulse pressure remains a significant independent predictor of all-cause, cardiovascular, and, in particular, coronary mortality.[17] There is a positive correlation between high pulse pressure and markers of inflammation, such as c-reactive protein.[18]

Cardiovascular disease and pulse pressure

Awareness of the effects of pulse pressure on morbidity and mortality is lacking relative to the awareness of the effects of elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure. However, pulse pressure has consistently been found to be a stronger independent predictor of cardiovascular events, especially in older populations, than has systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure.[3][11] This increased risk exists for both men and women and even when no other cardiovascular risk factors are present. The increased risk also exists even in cases in which high pulse pressure is caused by diastolic pressure decreasing over time while systolic remains steady or even slightly decreases.[19][17]

A meta-analysis in 2000 showed that a 10 mmHg increase in pulse pressure was associated with a 20% increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, and a 13% increase in risk for all coronary end points. The study authors also noted that, while risks of cardiovascular end points do increase with higher systolic pressures, at any given systolic blood pressure the risk of major cardiovascular end points increases, rather than decreases, with lower diastolic levels.[20] This suggests that interventions that lower diastolic pressure without also lowering systolic pressure (and thus lowering pulse pressure) could actually be counterproductive. Increased pulse pressure is also a risk factor for the development of atrial fibrillation.[21][9]

Effects of medications on pulse pressure

There are no drugs currently approved to lower pulse pressure. Although some anti-hypertensive drugs currently on the market may have the effect of modestly lowering pulse pressure, others may actually have the counterproductive effect of increasing pulse pressure. Among classes of drugs currently on the market, a 2020 review stated that

It has been hypothesized that vasopeptidase inhibitors and

A 2001 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 1,292 males, compared the effects of

Pulse pressure and sepsis

Diastolic blood pressure falls during the early stages of

See also

References

- ^ PMID 29494015. Retrieved 2019-07-21 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ^ PMID 21848774.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Pulse pressure". Cleveland Clinic. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

If you check your blood pressure regularly and notice you have an unusually wide (60 mmHg or more) or narrow pulse pressure (where your pulse pressure is less than one-quarter of the top blood pressure number), you should schedule an appointment with your healthcare provider to talk about it. [...] Pulse pressures of 50 mmHg or more can increase your risk of heart disease, heart rhythm disorders, stroke and more. Higher pulse pressures are also thought to play a role in eye and kidney damage from diseases like diabetes.

- ^ Weber CO (24 February 2022). Shah A (ed.). "Pulse Pressure". about.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009.

- ^ Klabunde RE (29 March 2007). "Arterial pulse pressure". Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008.

- S2CID 24409022.

- PMID 28616542.

- ISBN 978-1-880696-31-6.

- ^ PMID 29494015, retrieved 2023-10-25

- ^ S2CID 19241872.

- ^ S2CID 7092379.

- ^ "What is Arterial Stiffness?". News-Medical.net. 23 Nov 2009. Retrieved 18 Nov 2023.

- ^ PMID 32986936. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ PMID 31747208.

- ^ PMID 16908722.

- PMID 10373221.

- ^ PMID 9403561.

- PMID 17075211.

- PMID 10421594.

- ^ PMID 10789600.

- PMID 28450367.

- PMID 17904083. Retrieved 18 Nov 2023.

- PMID 20606908.

- PMID 26653692.