Quebec Agreement

| Articles of Agreement Governing Collaboration Between the Authorities of the U.S.A. and U.K. in the Matter of Tube Alloys | |

|---|---|

| Signed | 19 August 1943 |

| Location | Quebec City, Quebec, Canada |

| Effective | 19 August 1943 |

| Expiration | 7 January 1948 |

| Signatories |

|

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt on 19 August 1943, during World War II, at the First Quebec Conference in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

The Quebec Agreement stipulated that the US and UK would pool their resources to develop nuclear weapons, and that neither country would use them against the other, or against other countries without mutual consent, or pass information about them to other countries. It also gave the United States a veto over post-war British commercial or industrial uses of nuclear energy. The agreement merged the British Tube Alloys project with the American Manhattan Project, and created the Combined Policy Committee to control the joint project. Although Canada was not a signatory, the Agreement provided for a Canadian representative on the Combined Policy Committee in view of Canada's contribution to the effort.

British scientists performed important work as part of the

Background

Tube Alloys

The

The discovery of fission raised the possibility that an extremely powerful

Oliphant's team reached a strikingly different conclusion. He had delegated the task to two German refugee scientists, Rudolf Peierls and Frisch, who could not work on the university's secret projects like radar because they were enemy aliens, and therefore lacked the necessary security clearance.[12] They calculated the critical mass of a metallic sphere of pure uranium-235, and found that instead of tons, as everyone had assumed, as little as 1 to 10 kilograms (2.2 to 22.0 lb) would suffice, and would explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite.[13][14][15]

Oliphant took the

In July 1941, the MAUD Committee produced two comprehensive reports that concluded that an atomic bomb was not only technically feasible, but could be produced before the war ended, perhaps in as little as two years. The MAUD Committee unanimously recommended pursuing its development as a matter of urgency, although it recognised that the resources required might be beyond those available to Britain.[19][20] But even before its report was completed, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, had been briefed on its findings by his scientific advisor, Frederick Lindemann, and had decided on a course of action. A new directorate known by the deliberately misleading name of Tube Alloys was created to co-ordinate this effort. Sir John Anderson, the Lord President of the Council, became the minister responsible, and Wallace Akers from Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was appointed its director.[21]

Early American efforts

The prospect of Germany developing an atomic bomb was also of great concern to scientists in the United States, particularly those who were refugees from

One of Bush's first actions as the chairman of the NDRC was to arrange a clandestine meeting with

Among the wealth of information that the

Kenneth Bainbridge from Harvard University attended a MAUD Committee meeting on 9 April 1941, and was surprised to discover that the British were convinced that an atomic bomb was technically feasible.[31][32] The Uranium Committee met at Harvard on 5 May, and Bainbridge presented his report. Bush engaged a group headed by Arthur Compton, a Nobel laureate in physics and chairman of the Department of Physics at the University of Chicago, to investigate further. Compton's report, issued on 17 May 1941, did not address the design or manufacture of a bomb in detail.[33] Instead it endorsed a post-war project concentrating on atomic energy for power production.[34] On 28 June 1941, Roosevelt created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), with Bush as its director, personally responsible to the president. The new organisation subsumed the NDRC, now chaired by James B. Conant,[24] the President of Harvard University.[35] The Uranium Committee became the Uranium Section of the OSRD, but was soon renamed the S-1 Section for security reasons.[36][37]

Britain was at war, but the US was not. Oliphant flew to the United States in late August 1941, ostensibly to discuss the radar programme, but actually to find out why the United States was ignoring the MAUD Committee's findings.

Bush and Conant received the final MAUD Report from Thomson on 3 October 1941.[38] With this in hand, Bush met with Roosevelt and Vice-President Henry A. Wallace at the White House on 9 October 1941, and obtained a commitment to an expanded and expedited American atomic bomb project.[42] Two days later, Roosevelt sent a letter to Churchill in which he proposed that they exchange views "in order that any extended efforts may be coordinated or even jointly conducted."[43]

Collaboration

Roosevelt regarded this offer of a joint project as sufficiently important to have the letter personally delivered by

The Japanese

The American effort soon overtook the British. British scientists who visited the United States in 1942 were astounded at the progress and momentum the Manhattan Project had assumed.[55] On 30 July 1942, Anderson advised Churchill that: "We must face the fact that ... [our] pioneering work ... is a dwindling asset and that, unless we capitalise it quickly, we shall be outstripped. We now have a real contribution to make to a 'merger'. Soon we shall have little or none".[56] But Bush and Conant had already decided that British help was no longer needed.[57] In October 1942, they convinced Roosevelt that the United States should independently develop the atomic bomb, despite the agreement of unrestricted scientific interchange between the US and Britain.[58]

The positions of the two countries were the reverse of what they had been in 1941.

The Tube Alloys Directorate considered whether Britain could produce a bomb without American help. A gaseous diffusion plant to produce 1 kg of

By March 1943 Bush and Conant had decided that British help would benefit some areas of the Manhattan Project. In particular, it could benefit enough from assistance from Chadwick and one or two other British scientists to warrant the risk of revealing weapon design secrets.

Negotiations

Churchill took up the matter with Roosevelt when they met at the Washington Conference on 25 May 1943.[64] A meeting was arranged that afternoon between Cherwell and Bush in Hopkins's office in the White House, with Hopkins looking on. Both stated their respective positions, and Cherwell explained that Britain's post-war interest was in nuclear weapons, and not commercial opportunities.[65] Hopkins reported back to Roosevelt,[64] and Churchill and Roosevelt agreed that information interchange should be reviewed, and that the atomic bomb project should be a joint one.[66] Hopkins sent Churchill a telegram confirming this on 17 June,[64] but American policy did not change, largely because Roosevelt did not inform Bush when they next met on 24 June.[65][67] When Churchill pressed for action in a telegram on 9 July, Hopkins counselled Roosevelt that "you made a firm commitment to Churchill in regard to this when he was here and there is nothing to do but go through with it."[68]

Bush was in London on 15 July 1943 to attend a meeting of the British

Stimson had just finished a series of arguments with the British about the need for an invasion of France. He was reluctant to appear to disagree with them about everything,[69] and, unlike Bush, was sensitive to insinuations that Britain was being unfairly treated.[71] He spoke in conciliatory terms about the need for good post-war relations between the two countries. For his part, Churchill disavowed interest in the commercial applications of nuclear technology.[69] The reason for British concern about the post-war co-operation, they explained, was not commercial concerns, but so that Britain would have nuclear weapons after the war. Bush then proposed a five-point plan, which Stimson promised to put before the president for approval.[72]

Anderson drafted an agreement for full interchange, which Churchill re-worded "in more majestic language".

Agreement

A speedy drafting process was required because Roosevelt, Churchill and their political and military advisors converged for the

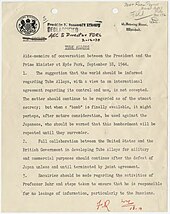

On 19 August Roosevelt and Churchill signed the Quebec Agreement, which was typed on four pages of Citadelle notepaper,[80] and formally titled "Articles of Agreement governing collaboration between the authorities of the USA and UK in the matter of Tube Alloys".[81] The United Kingdom and the United States agreed that "it is vital to our common safety in the present War to bring the Tube Alloys project to fruition at the earliest moment",[81] and that this was best accomplished by pooling their resources.[81] The Quebec Agreement stipulated that:

- The US and UK would pool their resources to develop nuclear weapons with a free exchange of information;

- Neither country would use them against the other;

- Neither country would use them against other countries without consent;

- Neither country would pass information about them to other countries without consent;

- That "in view of the heavy burden of production falling, upon the United States", the President might limit post-war British commercial or industrial uses of atomic energy.[81]

The only part of the Quebec Agreement that troubled Stimson was the requirement for mutual consent before atomic bombs could be used.

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement. Its terms were known to but a few insiders, and its very existence was not revealed to the

Implementation

Even before the Quebec Agreement was signed, Akers had already cabled London with instructions that Chadwick, Peierls, Oliphant and Simon should leave immediately for North America. They arrived on 19 August, the day it was signed, expecting to be able to talk to American scientists, but were unable to do so. Two weeks passed before American officials learned of the contents of the Quebec Agreement.[90] Bush told Akers that his action was premature, and that the Combined Policy Committee would first have to agree on the rules governing the employment of British scientists. With nothing to do, the scientists returned to the UK.[91] Groves briefed the OSRD S-1 Executive Committee, which had replaced the S-1 Committee on 19 June 1942,[92] at a special meeting on 10 September 1943.[93] The text of the Quebec Agreement was vague in places, with loopholes that Groves could exploit to enforce compartmentalisation.[94] Negotiations on the terms of technical interchange dragged on until December 1943. The new procedures went into effect on 14 December with the approval of the Military Policy Committee (which governed the Manhattan Project) and the Combined Policy Committee. By this time British scientists had already commenced working in the United States.[95][96]

Over the next two years, the Combined Policy Committee met only eight times.

There remained the issue of co-operation between the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago and the Montreal Laboratory. At the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 17 February 1944, Chadwick pressed for resources to build a nuclear reactor at what is now known as the Chalk River Laboratories. Britain and Canada agreed to pay the cost of this project, but the United States had to supply the heavy water. Because it was unlikely to have any impact on the war, Conant in particular was cool about the proposal, but heavy water reactors were still of great interest.[100] Groves was willing to support the effort and supply the heavy water required, but with certain restrictions. The Montreal Laboratory would have access to data from the Metallurgical Laboratory's research reactors at Argonne and the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge, but not from the production reactors at the Hanford Site; nor would they be given any information about the chemistry of plutonium, or of methods for separating it from other elements. This arrangement was formally approved by the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 19 September 1944.[101][102]

Chadwick supported the

A major strain on the Agreement came up in 1944, when it was revealed to the United States that the United Kingdom had made a secret agreement with

The issue of patent rights was a complex one, and attempts to negotiate deals between Britain and the United States in 1942, and between Britain and Canada in 1943, had failed. After the Quebec Agreement was signed, British and American experts sat down together again and hammered out an agreement, which was endorsed by the Combined Policy Committee in September 1944. This agreement, which also covered Canada, was retrospective to the signing of the Quebec Agreement in August 1943, but owing to necessary secrecy, was not finalised until 1956, and covered all patents held in November 1955. Each of the three countries agreed to transfer to the others any rights it held in the others' countries, and waive any claims for compensation against them.[111]

Llewellin returned to the United Kingdom at the end of 1943 and was replaced on the committee by Sir Ronald Ian Campbell, the deputy head of the British Mission to the United States, who in turn was replaced by the British Ambassador to the United States, Lord Halifax, in early 1945. Dill died in Washington on 4 November 1944, and was replaced both as Chief of the British Joint Staff Mission and as a member of the Combined Policy Committee by Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson.[97] It was therefore Wilson who, on 4 July 1945, under the clause of the Quebec Agreement that specified that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent, agreed that the use of nuclear weapons against Japan would be recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.[112][113][114]

Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire

In September 1944, a second wartime conference was held in Quebec known as the

Of Roosevelt's advisors, only Hopkins and Admiral

End of the Quebec Agreement

Truman, who had succeeded Roosevelt on the latter's death on 12 April 1945,

The next meeting of the Combined Policy Committee on 15 April 1946 produced no accord on collaboration, and resulted in an exchange of cables between Truman and Attlee. Truman cabled on 20 April that he did not see the communiqué he had signed as obligating the United States to assist Britain in designing, constructing and operating an atomic energy plant.[128] Attlee's response on 6 June 1946[129] "did not mince words nor conceal his displeasure behind the nuances of diplomatic language."[128] At issue was not just technical co-operation, which was fast disappearing, but the allocation of uranium ore. During the war this was of little concern, as Britain had not needed any ore, so all the production of the Congo mines and all the ore seized by the Alsos Mission had gone to the United States, but now it was also required by the British atomic project. Chadwick and Groves reached an agreement by which ore would be shared equally.[130]

The defection of

As the

Footnotes

Notes

- ^ Clark 1961, p. 9.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Clark 1961, p. 5.

- ^ Clark 1961, p. 11.

- ^ Bernstein 2011, p. 240.

- ^ Zimmerman 1995, p. 262.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 23–29.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, pp. 15–24.

- ^ Clark 1961, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 34–39.

- ^ Szasz 1992, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 39–41.

- Frisch, Otto (March 1940). Frisch-Peierls Memorandum, March 1940. atomicarchive.com (Report). Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Bernstein 2011, pp. 440–446.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Laucht 2012, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c Phelps 2010, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 42.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 106–111.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 16–20.

- ^ a b Rhodes 1986, pp. 337–338.

- ^ a b Shrader 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Phelps 2010, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 204.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 34–39.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 40.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 29, 37–38.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 24.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 41.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 39.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 372–374.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 373.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 205.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, p. 194.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 123–125.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, p. 302.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 389–393.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 72–75.

- ^ a b Jones 1985, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Paul 2000, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Bernstein 1976, p. 208.

- ^ a b Bernstein 1976, pp. 209–213.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, p. 224.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, p. 218.

- ^ a b Bernstein 1976, p. 210.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 162–165.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 213.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Paul 2000, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Farmelo 2013, p. 229.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 214.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 274.

- ^ a b c d Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 216.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 277.

- ^ a b Gowing 1964, p. 168.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 278.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 170.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, p. 236.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b Gowing 1964, p. 171.

- ^ a b Farmelo 2013, pp. 229–231.

- ^ a b c d Gowing 1964, p. 439.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 119.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 52.

- ^ a b Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Botti 1987, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 492.

- ^ Tyrer 2016, pp. 802, 807–808.

- ^ a b c Jones 1985, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Paul 2000, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 75.

- ^ Paul 2000, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Jones 1985, p. 245.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 241.

- ^ a b Gowing 1964, p. 234.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 173.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 280.

- Laurence, George C. (May 1980). "Early Years of Nuclear Energy Research in Canada". Atomic Energy of Canada Limited. Archivedfrom the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 271–276.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 241–244.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 250–256.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 256–260.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 260–267.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 291–295.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 343–346.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 372.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 372–373.

- ^ "Minutes of a Meeting of the Combined Policy Committee, Washington, July 4, 1945". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Aide-Mémoire Initialed by President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill". Foreign Relations of the United States, Conference at Quebec, 1944. Office of the Historian, United States State Department. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Paul 2000, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 327.

- ^ Bernstein 1976, p. 224.

- ^ Paul 2000, p. 68.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 457–458.

- ^ Paul 2000, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Nichols 1987, p. 177.

- ^ Groves 1962, pp. 401–402.

- ^ a b Paul 2000, pp. 80–83.

- ^ "Draft agreement dated November 16, 1945". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Minutes of a Meeting of the Combined Policy Committee, December 4, 1945". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ a b Paul 2000, p. 88.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 126–130.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 480–481.

- ^ Gott 1963, p. 240.

- ^ Jones 1985, pp. 576–578.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Farmelo 2013, p. 322.

- ^ Calder 1953, pp. 303–306.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, p. 250.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 245–254.

- ^ "Minutes of the Meeting of the Combined Policy Committee, at Blair House, Washington, D.C., January 7, 1948". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ Paul 2000, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b Young, Ken. "Trust and Suspicion in Anglo-American Security Relations: the Curious Case of John Strachey". History Working Papers Project. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Gott 1963, pp. 245–247.

- ^ "Public Law 85-479" (PDF). US Government Printing Office. 2 July 1958. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

References

- JSTOR 448105.

- ISSN 0002-9505.

- Botti, Timothy J. (1987). The Long Wait: the Forging of the Anglo-American Nuclear Alliance, 1945–58. Contributions in Military Studies. New York: Greenwood Press. OCLC 464084495.

- Calder, Ritchie (17 October 1953). "Cost of Atomic Secrecy: Anglo-US Rivalry". ISSN 0027-8378.

- OCLC 824335.

- ISBN 978-0-465-02195-6.

- JSTOR 2611300.

- OCLC 3195209.

- Gowing, Margaret; OCLC 611555258.

- OCLC 932666584.

- OCLC 493738019. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb (PDF). Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 10913875. Archived from the original(PDF) on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- Laucht, Christoph (2012). Elemental Germans: Klaus Fuchs, Rudolf Peierls and the making of British nuclear culture 1939–59. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-02833-4.

- OCLC 15223648.

- Paul, Septimus H. (2000). Nuclear Rivals: Anglo-American Atomic Relations, 1941–1952. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press. OCLC 43615254.

- Phelps, Stephen (2010). The Tizard Mission: the Top-Secret Operation that Changed the Course of World War II. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme. OCLC 642846903.

- OCLC 505347006.

- OCLC 13793436.

- Shrader, Charles R. (2006). History of Operations Research in the United States Army, Volume I: 1942–62. Washington, D.C.: US Army. OCLC 73821793.

- Szasz, Ferenc Morton (1992). British Scientists and the Manhattan Project: the Los Alamos Years. New York: St. Martin's Press. OCLC 23901666.

- Tyrer, William A. (2016). "The Unresolved Mystery of ELLI". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 29 (4): 785–808. ISSN 0885-0607.

- Zimmerman, David (1995). "The Tizard Mission and the Development of the Atomic Bomb". War in History. 2 (3): 259–273. ISSN 0968-3445.