Quinine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | US: /ˈkwaɪnaɪn/, /kwɪˈniːn/ or UK: /ˈkwɪniːn/ KWIN-een |

| Trade names | Qualaquin, Quinbisul, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682322 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

intravenous, rectal | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 70–95%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP3A4 and CYP2C19-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 8–14 hours (adults), 6–12 hours (children)[4] |

| Excretion | Kidney (20%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 177 °C (351 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Quinine is a medication used to treat

Common side effects include headache,

Quinine was first isolated in 1820 from the bark of a

Uses

Medical

As of 2006, quinine is no longer recommended by the

Quinine was frequently prescribed as an

Available forms

Quinine is a basic

All quinine salts may be given orally or intravenously (IV); quinine gluconate may also be given intramuscularly (IM) or rectally (PR).[23][24] The main problem with rectal administration is that the dose can be expelled before it is completely absorbed; in practice, this is corrected by giving a further half dose. No injectable preparation of quinine is licensed in the US; quinidine is used instead.[25][26]

| Name | Amount equivalent to 100 mg quinine base |

|---|---|

| Quinine base | 100 mg |

| Quinine bisulfate | 169 mg |

| Quinine dihydrochloride | 122 mg |

| Quinine gluconate | 160 mg |

| Quinine hydrochloride | 111 mg |

| Quinine sulfate dihydrate [(quinine)2H2SO4∙2H2O] | 121 mg |

Beverages

Quinine is a flavor component of tonic water and bitter lemon drink mixers. On the soda gun behind many bars, tonic water is designated by the letter "Q" representing quinine.[27]

Tonic water was initially marketed as a means of delivering quinine to consumers in order to offer anti-malarial protection. According to tradition, because of the bitter taste of anti-malarial quinine tonic, British colonials in India mixed it with gin to make it more palatable, thus creating the gin and tonic cocktail, which is still popular today.[28] While it is possible to drink enough tonic water to temporarily achieve quinine levels that offer anti-malarial protection, it is not a sustainable long-term means of protection.[29]

In France, quinine is an ingredient of an

As a flavouring agent in drinks, quinine is limited to 83

Scientific

Quinine (and quinidine) are used as the chiral moiety for the ligands used in Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation as well as for numerous other chiral catalyst backbones. Because of its relatively constant and well-known fluorescence quantum yield, quinine is used in photochemistry as a common fluorescence standard.[33][34]

Contraindications

Because of the narrow difference between its therapeutic and toxic effects, quinine is a common cause of drug-induced disorders, including

Quinine can cause

While not necessarily an absolute contraindication, concomitant administration of quinine with drugs primarily metabolized by CYP2D6 may lead to higher than expected plasma concentrations of the drug, due to quinine's strong inhibition of the enzyme.[38]

Adverse effects

Quinine can cause unpredictable serious and life-threatening blood and cardiovascular reactions including

The most common adverse effects involve a group of symptoms called cinchonism, which can include headache, vasodilation and sweating, nausea, tinnitus, hearing impairment, vertigo or dizziness, blurred vision, and disturbance in color perception.[5][35][37] More severe cinchonism includes vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, deafness, blindness, and disturbances in heart rhythms.[37] Cinchonism is much less common when quinine is given by mouth, but oral quinine is not well tolerated (quinine is exceedingly bitter and many people will vomit after ingesting quinine tablets).[5] Other drugs, such as Fansidar (sulfadoxine with pyrimethamine) or Malarone (proguanil with atovaquone), are often used when oral therapy is required. Quinine ethyl carbonate is tasteless and odourless,[39] but is available commercially only in Japan. Blood glucose, electrolyte and cardiac monitoring are not necessary when quinine is given by mouth.

Quinine has diverse unwanted interactions with numerous prescription drugs, such as potentiating the anticoagulant effects of warfarin.[5] It is a strong inhibitor of CYP2D6,[38] an enzyme involved in the metabolism of many drugs.

Mechanism of action

This section is missing information about cramp mechanism; MAOI action aforementioned. (December 2022) |

Quinine is used for its

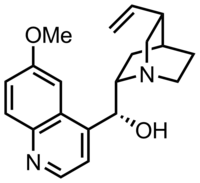

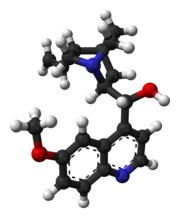

Chemistry

The

Synthesis

Biosynthesis

In the first step of quinine biosynthesis, the enzyme strictosidine synthase catalyzes a stereoselective Pictet–Spengler reaction between tryptamine and secologanin to yield strictosidine.[46][47] Suitable modification of strictosidine leads to an aldehyde. Hydrolysis and decarboxylation would initially remove one carbon from the iridoid portion and produce corynantheal. Then the tryptamine side-chain were cleaved adjacent to the nitrogen, and this nitrogen was then bonded to the acetaldehyde function to yield cinchonaminal. Ring opening in the indole heterocyclic ring could generate new amine and keto functions. The new quinoline heterocycle would then be formed by combining this amine with the aldehyde produced in the tryptamine side-chain cleavage, giving cinchonidinone. For the last step, hydroxylation and methylation gives quinine.[48][49]

Catalysis

Quinine and other

History

Quinine was used as a muscle relaxant by the

Spanish

A popular story of how it was brought to Europe by the

The

The form of quinine most effective in treating malaria was found by

Quinine played a significant role in the colonization of Africa by Europeans. The availability of quinine for treatment had been said to be the prime reason Africa ceased to be known as the "white man's grave". A historian said, "it was quinine's efficacy that gave colonists fresh opportunities to swarm into the Gold Coast, Nigeria and other parts of west Africa".[64]

To maintain their monopoly on cinchona bark, Peru and surrounding countries began outlawing the export of cinchona seeds and saplings in the early 19th century. In 1865, Manuel Incra Mamani collected seeds from a plant particularly high in quinine and provided them to Charles Ledger. Ledger sent them to his brother, who sold them to the Dutch government. Mamani was arrested on a seed collecting trip in 1871, and beaten so severely, likely because of providing the seeds to foreigners, that he died soon afterwards.[65]

By the late 19th century the Dutch grew the plants in Indonesian plantations. Soon they became the main suppliers of the tree. In 1913 they set up the Kina Bureau, a cartel of cinchona producers charged with controlling price and production.[66] By the 1930s Dutch plantations in Java were producing 22 million pounds of cinchona bark, or 97% of the world's quinine production.[64] U.S. attempts to prosecute the Kina Bureau proved unsuccessful.[66]

During World War II, Allied powers were cut off from their supply of quinine when Germany conquered the Netherlands, and Japan controlled the Philippines and Indonesia. The US had obtained four million cinchona seeds from the Philippines and began operating cinchona plantations in Costa Rica. Additionally, they began harvesting wild cinchona bark during the Cinchona Missions. Such supplies came too late. Tens of thousands of US troops in Africa and the South Pacific died of malaria due to the lack of quinine.[64] Despite controlling the supply, the Japanese did not make effective use of quinine, and thousands of Japanese troops in the southwest Pacific died as a result.[67][68][69][70]

Quinine remained the antimalarial drug of choice until after World War II. Since then, other drugs that have fewer side effects, such as chloroquine, have largely replaced it.[71]

Bromo Quinine were

Conducting research in central Missouri, John S. Sappington independently developed an anti-malaria pill from quinine. Sappington began importing cinchona bark from Peru in 1820. In 1832, using quinine derived from the cinchona bark, Sappington developed a pill to treat a variety of fevers, such as scarlet fever, yellow fever, and influenza in addition to malaria. These illnesses were widespread in the Missouri and Mississippi valleys. He manufactured and sold "Dr. Sappington's Anti-Fever Pills" across Missouri. Demand became so great that within three years, Sappington founded a company known as Sappington and Sons to sell his pills nationwide.[73]

Society and culture

Natural occurrence

The bark of Remijia contains 0.5–2% of quinine. The bark is cheaper than bark of Cinchona. As it has an intense taste, it is used for making tonic water.[74]

Regulation in the US

From 1969, to 1992, the US

Though Legatrin was banned by the FDA for the treatment of leg cramps, the drug manufacturer URL Mutual has branded a quinine-containing drug named Qualaquin. It is marketed as a treatment for malaria and is sold in the United States only by prescription. In 2004, the CDC reported only 1,347 confirmed cases of malaria in the United States.[77]

Termination of pregnancy

For much of the 20th century, women's use of an overdose of quinine to deliberately terminate a pregnancy was a relatively common abortion method in various parts of the world, including China.[78]

Cutting agent

Quinine is sometimes detected as a

Other animals

Quinine is used as a treatment for

References

- ^ "Quinine International". Drugs.com. 2 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Quinine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 25 March 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Qualaquin (quinine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Quinine sulfate". Drugs.com. 20 February 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- PMID 31210357.

- ISBN 978-0-815-18450-8. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2016.

- ISBN 9780203502327.

- ISBN 9780470582268. Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.

- .

- ISBN 9783034604796.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "Quinine". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ World Health Organization (2006). "Guidelines for the treatment of malaria" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- S2CID 173027.

- S2CID 206891479.

- PMID 19622553.

- ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: New risk management plan and patient Medication Guide for Qualaquin (quinine sulfate)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Serious risks associated with using Quinine to prevent or treat nocturnal leg cramps (September 2012)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ "Quinine for Night-Time Leg Cramps". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- PMID 2743481.

- PMID 8735679.

- PMID 16675812.

- PMID 1850497.

- PMID 16000347.

- ISBN 978-1-4022-0804-1.

- ^ Khosla S (17 March 2017). "Gin and Tonic: The fascinating story behind the invention of the classic English cocktail". India.com. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- S2CID 24261782.

- S2CID 26907917.

- ^ "Food Additive Status List". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 872/2012". EUR-Lex. Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-46312-4.

- ^ a b Prahl S. "Quinine sulfate". OMLC. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ PMID 26822544.

- ISSN 2053-6178.

- ^ a b c d e "US label: quinine sulfate" (PDF). FDA. April 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2017.

- ^ PMID 27618912.

- PMID 3358888.

- ^ Wishart DS, Djombou Feunang Y, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, Grant JR, et al. "Quinine | DrugBank Online". DrugBank. 5.0.

- PMID 9088993.

- ^ Lowe D (22 January 2019). "Quinine's Target". Science. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "Basic Concepts in Fluorescence". Archived from the original on 13 September 2012.

- ^ Woodward R, Doering W (1944). "The Total Synthesis of Quinine". .

- .

- PMID 510306.

- PMID 476085.

- ISBN 9780470742761.

- PMID 16874388.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-26418-7

- ^ Flückiger FA, Hanbury D (1874). "Cortex Cinchonæ". Pharmacographia: A History of the Principal Drugs of Vegetable Origin, Met with in Great Britain and British India. London: Macmillan and Co. pp. 302–331.

- ISBN 978-1-7862-7522-6.

- ^ See:

- Ortiz Crespo FI (1995). "Fragoso, Monardes and pre-Chinchonian knowledge of Cinchona". Archives of Natural History. 22 (2): 169–181. ISSN 0260-9541.

- Stuart DC (2004). Dangerous Garden: The Quest for Plants to Change Our Lives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-674-01104-5.

- Monardes N (1580). Primera y segunda y tercera partes de la Historia medicinal, de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales, que sirven en Medicina [First and second and third parts of medicinal History, of the things that are brought from our West Indies, which are used in Medicine] (in Spanish). Seville, Spain: Fernando Díaz. pp. 74–75.

Del nuevo Reyno, traen una corteza, que dizen ser de un arbol, que es de mucha grandeza: el qual dizen que lleva unas hojas en forma de coraçon, y que no lleva fruto. Este arbol tiene una corteza gruessa, muy solida y dura, que en esto y en el color parece mucho a la corteza del palo que llaman Guayacan: en la superficie tiene una pelicula delgada blanquisca, quebrada por toda ella: tiene la corteza mas de un dedo de gruesso, solida y pesada: la qual gustada tiene notable amargor, como el de la Genciana: tiene en el gusto notable astriction, con alguna aromaticidad, porque al fin de mascar la respica della buen olor. Tienen los Indios esta corteza en mucho, y usan della en todo genero de camaras, que sean con sangre, o sin ella. Los Españoles fatigados de aquesta enfermedad, por aviso de los Indios, han usado de aquesta corteza y han sanado muchos dellos con ella.

[From the new kingdom, there is brought a bark, which is said to be from a tree, which is very large: it is said that it bears leaves in the form of a heart, and that it bears no fruit. This tree has a thick bark, very solid and hard, that in this and in its color looks much like the bark of the tree that is called guayacán: on the surface, it has a thin, discontinuous whitish film throughout it: it has bark more than one finger thick, solid and heavy: which, when tasted, has a considerable bitterness, like that of the gentian: it has in its taste a considerable astringency, with some aromaticity, because at the end of chewing it, one breathes with a sweet odor. The Indians hold this bark in high regard, and use it for all sorts of diarrhea, that are with blood [i.e., bloody] and without it. The Spanish [who are] tired of this disease, on the advice of the Indians, have used this bark and have healed many of those with it. They take as much as a small bean, make [it into] powder, take it in red wine or in appropriate water, if they have fever or illness: it must be taken in the morning on an empty stomach, three or four times: otherwise, using the order and regimen that suits those who have diarrhea.]

Toman della tanto como una haba pequeña hecha polvos, tomase en vino tinto, o en agua apropiada, como tienen la calentura, o mal: hase de tomar por la mañana en ayunas, tres o quatro vezes: usando en lo demas, la orden y regimiento que conviene a los que tienen camaras. - Fragoso J (1572). Discursos de las cosas aromaticas, arboles y frutales, y de otras muchas medicinas simples que se traen de la India Oriental y que sirven al uso de medicina [Discourse on fragrant things, trees and fruits, as well as many other ordinary medicines that have been brought from India and the Orient and are of use to medicine] (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Francisco Sánchez. p. 35.

En el nuevo mundo ay un grande arbol que lleva las hojas a forma de coraçon, y carece de fruto. Tiene dos cortezas, la una gruessa muy solida y dura, que assi en la sustancia como en el color es muy semejante al Guayacan: la otra es mas delgada y blanquezina, la qual es amarga con alguna estipticidad: y demas desto es aromatica. Tienenla en mucho nuestros Indios, porque la usan contra qualesquier camaras, tomando del polvo peso de una drama o poco mas, desatado en agua azerada, o vino tinto.

[In the new world, there is a big tree that bears leaves in the form of a heart, and lacks fruit. It has two barks, one [is] thick, very solid, [and] hard, which in substance as well as in color is much like guayacan [i.e., lignum vitae]: the other is thinner and whitish, which is bitter with some styptic [i.e., astringent] quality: and besides this, it is aromatic. Our Indians regard it highly, because they use it against any diarrheas, taking a weight of a dram or a bit more of the powder, mixing it in mineral water, or red wine.]

- Ortiz Crespo FI (1995). "Fragoso, Monardes and pre-Chinchonian knowledge of Cinchona". Archives of Natural History. 22 (2): 169–181.

- PMID 21609473.

- ^ Pain S (15 September 2001). "The Countess and the cure". New Scientist.

- Society of Jesus]. Varones ilustres de la Compañía de Jesús (in Spanish). Vol. 5. Original series by Juan Eusebio Nieremberg. Madrid, Spain: José Fernandez de Buendía (published 1666). pp. 612–628. p. 612:]

Naciò el Hermano Agustin Salumbrino el año de mil y quinientos y sesenta y quatro en la Ciudad de Fḷọṛi en la Romania […]

[Brother Agustino Salumbrino was born in the year 1564 in the city of Forlì in Romagna - ^ See:

- Medina Rodríguez F, Aceves Ávila FJ, Moreno Rodríguez J (2007). "Precisions on the History of Quinine". Reumatología Clínica. Letters to the Editor. 3 (4): 194–196. ISSN 2173-5743.

In fact, though the last wordon this has not yet been spoken, there are Jesuit texts thatmention that quinine reached Rome in 1632, with theprovincial of the Jesuit missions in Peru, father AlonsoMessia Venegas, as its introducer, when he brought asample of the bark to present it as a primacy, and whohad left Lima 2 years earlier, because evidence of his stayin Seville 1632 has been registered, publishing one of hisbooks there and following his way to Rome as a procurator.

- Torres Saldamando E (June 1882). "El P. Diego de Torres Vazquez". Los antiguos jesuitas del Perú (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Imprenta Liberal. pp. 180–181. p. 181:

Al siguiente año se dirigieron á Europa los Procuradores P. Alonso Messía Venegas y P. Hernando de Leon Garavito, llevando gran cantidad de la corteza de la quina, cuyo conocimiento extendieron por el mundo los jesuitas.

[In the following year [i.e., 1631] there went to Europe the procurators Father Alonso Messia Venegas and Father Hernando de Leon Garavito, taking a great quantity of cinchona bark, knowledge of which the Jesuits spread throughout the world.] - Bailetti A. "Capítulo 10: La Condesa de Chinchón". LA MISIÓN DEL JESUITA AGUSTÍN SALUMBRINO, la malaria y el árbol de quina.

A últimas horas de la tarde del treinta y uno de mayo de 1631 se hizo a la vela la Armada Real con dirección a Panamá llevando el precioso cargamento de oro y plata.

[Late in the afternoon of 31 May 1631, the royal armada set sail in the direction of Panama, carrying its multimillion [dollar] cargo of gold and silver.

En una de las naves viajaban los procuradores jesuitas padres Alonso Messia y Hernando León Garavito custodiando los fardos con la corteza de quina en polvo preparados por Salumbrino. Después de casi veinte días de navegación el inapreciable medicamento llegó a la ciudad de Panamá, donde fue descargado para cruzar en mulas el agreste camino del itsmo palúdico hasta Portobelo para seguir a Cartagena y la Habana, cruzar el Atlántico y llegar a Sanlúcar de Barrameda en Sevilla. […] Finalmente siguió su camino a Roma y a su destino final el Hospital del Espíritu Santo.

On one of the ships traveled the Jesuit procurators Fathers Alonso Messia and Hernando León Garavito, guarding the cases of powdered cinchona bark, prepared by Salumbrino. After almost 20 days of sailing, medicine arrived in the city of Panama, where it was transloaded onto mules. It then traveled the malarial isthmus as far as Portobelo, thence to Cartagena [in Colombia] and Havana. It then traveled to Sanlúcar de Barrameda in Seville, [Spain]. […] Finally it followed the road to Rome and to its final destination, the Hospital of the Holy Spirit]

- Medina Rodríguez F, Aceves Ávila FJ, Moreno Rodríguez J (2007). "Precisions on the History of Quinine". Reumatología Clínica. Letters to the Editor. 3 (4): 194–196.

- ^ Rocco F (2004). Quinine: malaria and the quest for a cure that changed the world. New York, NY: Perennial.

- ^ Humphrey L (2000). Quinine and Quarantine. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press.

- ^ Marie de la Condamine C (29 May 1737). "Sur l'arbre du quinquina". Histoire de l'Académie royale des sciences. Imprimerie Royale (published 1740). pp. 226–243.

- ^ De Jussieu accompanied de la Condamine on the latter's expedition to Peru: de Jussieu J (1737). Description de l'arbre à quinquina. Paris: Société du traitement des quinquinas (published 1934).

- ^ Pelletier PJ, Caventou JB (1820). "Recherches Chimiques sur les Quinquinas" [Continuation: Chemical Research on Quinquinas]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 15. Crochard: 337–365.

The authors name quinine on page 348: " …, nous avons cru devoir la nommer quinine, pour la distinguer de la cinchonine par un nom qui indique également son origine."

[…, we thought that we should name it "quinine" in order to distinguish it from cinchonine by means of a name that also indicates its origin.] - ^ Briquet P (1853). Traité thérapeutique du quinone et de ses préparations (in French). Paris: L. Martinet.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-393-04634-2.

- ^ Canales NA (7 April 2022). "Hunting lost plants in botanical collections". Wellcome Collection. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b Shah S (2010). The Fever: How Malaria Has Ruled Humankind for 500,000 Years. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 94.

- ^ Morton L (1953). "29". The Fall of the Philippines. Washington, D.C.: United States Army. p. 524. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- ^ Hawk A. "Remembering the war in New Guinea: Japanese Medical Corps – malaria". Archived from the original on 22 November 2011.

- ^ Heaton LD, ed. (1963). "8". Preventive Medicine in World War II: Volume VI, Communicable Diseases: Malaria. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. pp. 401 and 434. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012.

- ^ "Notes on Japanese Medical Services". Tactical and Technical Trends (36). 1943. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011.

- ^ Shah S (2010). The Fever: How Malaria Has Ruled Humankind for 500,000 Years. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 102.

- ^ "Medicine: What's Good for a Cold?". Time. 22 February 1960. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "John. S Sappington". Historic Missourians. State Historical Society of Missouri.

- ISBN 978-80-200-1179-4.

- ^ "FDA Orders Stop to Marketing of Quinine for Night Leg Cramps". FDA Consumer Magazine. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). July–August 1995. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ^ "FDA Orders Unapproved Quinine Drugs from the Market and Cautions Consumers About Off-Label Use of Quinine to Treat Leg Cramps" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 December 2006. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- PMID 16723971.

- OCLC 1366057905.

- ^ "Dimethyltryptamine and Ecstasy Mimic Tablets (Actually Containing 5-Methoxy-Methylisopropyltryptamine) in Oregon" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Department of Justice. October 2009. p. 79. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Porritt M. "Cryptocaryon irritans". Reef Culture Magazine (1 ed.). Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

Further reading

- Schroeder-Lein G (2008). The encyclopedia of Civil War medicine. Armonk, NY: Sharpe, Inc.

- ISBN 978-1-59376-049-6.

- Stockwell JR (October 1982). PMID 6983345.

- Wolff RS, Wirtschafter D, Adkinson C (June 1997). "Ocular quinine toxicity treated with hyperbaric oxygen". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 24 (2): 131–134. PMID 9171472. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2008.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link - Slater L (2009). War and disease : biomedical research on malaria in the twentieth century. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- JSTOR 25118388.

- World Health Organization (2015). Guidelines for the treatment of malaria (3rd ed.). ISBN 9789241549127.