r-process

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

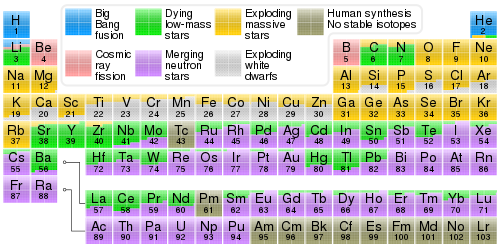

In nuclear astrophysics, the rapid neutron-capture process, also known as the r-process, is a set of nuclear reactions that is responsible for the creation of approximately half of the atomic nuclei heavier than iron, the "heavy elements", with the other half produced by the p-process and s-process. The r-process usually synthesizes the most neutron-rich stable isotopes of each heavy element. The r-process can typically synthesize the heaviest four isotopes of every heavy element; of these, the heavier two are called r-only nuclei because they are created exclusively via the r-process. Abundance peaks for the r-process occur near mass numbers A = 82 (elements Se, Br, and Kr), A = 130 (elements Te, I, and Xe) and A = 196 (elements Os, Ir, and Pt).

The r-process entails a succession of rapid

A limited r-process-like series of neutron captures occurs to a minor extent in

The r-process contrasts with the

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

Following pioneering research into the

The need for a physical setting providing rapid

The stationary r-process as described by the B2FH paper was first demonstrated in a time-dependent calculation at

The creation of free neutrons by electron capture during the rapid collapse to high density of a supernova core along with quick assembly of some neutron-rich seed nuclei makes the r-process a primary nucleosynthesis process, a process that can occur even in a star initially of pure H and He. This in contrast to the B2FH designation which is a secondary process building on preexisting iron. Primary stellar nucleosynthesis begins earlier in the galaxy than does secondary nucleosynthesis. Alternatively the high density of neutrons within neutron stars would be available for rapid assembly into r-process nuclei if a collision were to eject portions of a neutron star, which then rapidly expands freed from confinement. That sequence could also begin earlier in galactic time than would s-process nucleosynthesis; so each scenario fits the earlier growth of r-process abundances in the galaxy. Each of these scenarios is the subject of active theoretical research. Observational evidence of the early r-process enrichment of interstellar gas and of subsequent newly formed stars, as applied to the abundance evolution of the galaxy of stars, was first laid out by James W. Truran in 1981.[13] He and subsequent astronomers showed that the pattern of heavy-element abundances in the earliest metal-poor stars matched that of the shape of the solar r-process curve, as if the s-process component were missing. This was consistent with the hypothesis that the s-process had not yet begun to enrich interstellar gas when these young stars missing the s-process abundances were born from that gas, for it requires about 100 million years of galactic history for the s-process to get started whereas the r-process can begin after two million years. These s-process–poor, r-process–rich stellar compositions must have been born earlier than any s-process, showing that the r-process emerges from quickly evolving massive stars that become supernovae and leave neutron-star remnants that can merge with another neutron star. The primary nature of the early r-process thereby derives from observed abundance spectra in old stars[4] that had been born early, when the galactic metallicity was still small, but that nonetheless contain their complement of r-process nuclei.

Either interpretation, though generally supported by supernova experts, has yet to achieve a totally satisfactory calculation of r-process abundances because the overall problem is numerically formidable. However, existing results are supportive; in 2017, new data about the r-process was discovered when the LIGO and Virgo gravitational-wave observatories discovered a merger of two neutron stars ejecting r-process matter.[14] See Astrophysical sites below.

Noteworthy is that the r-process is responsible for our natural cohort of radioactive elements, such as uranium and thorium, as well as the most neutron-rich isotopes of each heavy element.

Nuclear physics

There are three natural candidate sites for r-process nucleosynthesis where the required conditions are thought to exist: low-mass supernovae, Type II supernovae, and neutron star mergers.[15]

Immediately after the severe compression of electrons in a Type II supernova,

Three processes which affect the climbing of the neutron drip line are a notable decrease in the neutron-capture cross section in nuclei with closed neutron shells, the inhibiting process of photodisintegration, and the degree of nuclear stability in the heavy-isotope region. Neutron captures in r-process nucleosynthesis leads to the formation of neutron-rich, weakly bound nuclei with neutron separation energies as low as 2 MeV.[16][1] At this stage, closed neutron shells at N = 50, 82, and 126 are reached, and neutron capture is temporarily paused. These so-called waiting points are characterized by increased binding energy relative to heavier isotopes, leading to low neutron capture cross sections and a buildup of semi-magic nuclei that are more stable toward beta decay.[17] In addition, nuclei beyond the shell closures are susceptible to quicker beta decay owing to their proximity to the drip line; for these nuclei, beta decay occurs before further neutron capture.[18] Waiting point nuclei are then allowed to beta decay toward stability before further neutron capture can occur,[1] resulting in a slowdown or freeze-out of the reaction.[17]

Decreasing nuclear stability terminates the r-process when its heaviest nuclei become unstable to spontaneous fission, when the total number of nucleons approaches 270. The

The r-process also occurs in thermonuclear weapons, and was responsible for the initial discovery of neutron-rich almost stable isotopes of actinides like plutonium-244 and the new elements einsteinium and fermium (atomic numbers 99 and 100) in the 1950s. It has been suggested that multiple nuclear explosions would make it possible to reach the island of stability, as the affected nuclides (starting with uranium-238 as seed nuclei) would not have time to beta decay all the way to the quickly spontaneously fissioning nuclides at the line of beta stability before absorbing more neutrons in the next explosion, thus providing a chance to reach neutron-rich superheavy nuclides like copernicium-291 and -293 which may have half-lives of centuries or millennia.[23]

Astrophysical sites

The most probable candidate site for the r-process has long been suggested to be core-collapse supernovae (spectral types Ib, Ic and II), which may provide the necessary physical conditions for the r-process. However, the very low abundance of r-process nuclei in the interstellar gas limits the amount each can have ejected. It requires either that only a small fraction of supernovae eject r-process nuclei to the interstellar medium, or that each supernova ejects only a very small amount of r-process material. The ejected material must be relatively neutron-rich, a condition which has been difficult to achieve in models,[2] so that astrophysicists remain uneasy about their adequacy for successful r-process yields.

In 2017, new astronomical data about the r-process was discovered in data from the merger of two neutron stars. Using the gravitational wave data captured in GW170817 to identify the location of the merger, several teams[24][25][26] observed and studied optical data of the merger, finding spectroscopic evidence of r-process material thrown off by the merging neutron stars. The bulk of this material seems to consist of two types: hot blue masses of highly radioactive r-process matter of lower-mass-range heavy nuclei (A < 140 such as strontium)[27] and cooler red masses of higher mass-number r-process nuclei (A > 140) rich in actinides (such as uranium, thorium, and californium). When released from the huge internal pressure of the neutron star, these ejecta expand and form seed heavy nuclei that rapidly capture free neutrons, and radiate detected optical light for about a week. Such duration of luminosity would not be possible without heating by internal radioactive decay, which is provided by r-process nuclei near their waiting points. Two distinct mass regions (A < 140 and A > 140) for the r-process yields have been known since the first time dependent calculations of the r-process.[10] Because of these spectroscopic features it has been argued that such nucleosynthesis in the Milky Way has been primarily ejecta from neutron-star mergers rather than from supernovae.[3]

These results offer a new possibility for clarifying six decades of uncertainty over the site of origin of r-process nuclei. Confirming relevance to the r-process is that it is radiogenic power from radioactive decay of r-process nuclei that maintains the visibility of these spun off r-process fragments. Otherwise they would dim quickly. Such alternative sites were first seriously proposed in 1974

See also

Notes

- ^ neutrons 1,674,927,471,000,000,000,000,000/cc vs 1 atom/cc interstellar space

- ^ Neutron number 50, 82 and 126

- ^ Abundance peaks for the r- and s-processes are at A = 80, 130, 196 and A = 90, 138, 208, respectively.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Burbidge, E. M.; Burbidge, G. R.; Fowler, W. A.; Hoyle, F. (1957). "Synthesis of the Elements in Stars". .

- ^ a b

S2CID 119412716.

- ^ a b

Kasen, D.; Metzger, B.; Barnes, J.; Quataert, E.; Ramirez-Ruiz, E. (2017). "Origin of the heavy elements in binary neutron-star mergers from a gravitational-wave event". PMID 29094687.

- ^ a b

Frebel, A.; Beers, T. C. (2018). "The formation of the heaviest elements". .

Nuclear physicists are still working to model the r-process, and astrophysicists need to estimate the frequency of neutron-star mergers to assess whether r-process heavy-element production solely or at least significantly takes place in the merger environment.

- .

- ^ a b Hoyle, F. (1946). "The Synthesis of the Elements from Hydrogen". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 106 (5): 343–383. .

- .

- S2CID 186549912.

- ^

Cameron, A. G. W. (1957). "Nuclear reactions in stars and nucleogenesis". doi:10.1086/127051.

- ^ a b

Seeger, P. A.; Fowler, W. A.; Clayton, D. D. (1965). "Nucleosynthesis of heavy elements by neutron capture". doi:10.1086/190111.

- ^ See Seeger, Fowler & Clayton 1965. Figure 16 shows the short-flux calculation and its comparison with natural r-process abundances whereas Figure 18 shows the calculated abundances for long neutron fluxes.

- ^ See Table 4 in Seeger, Fowler & Clayton 1965.

- ^

Truran, J. W. (1981). "A new interpretation of the heavy-element abundances in metal-deficient stars". Bibcode:1981A&A....97..391T.

- ^

Abbott, B. P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (2017). "GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral". PMID 29099225.

- doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.74.015802. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-06-17.

- S2CID 250790169.

- ^ a b Eichler, M.A. (2016). Nucleosynthesis in explosive environments: neutron star mergers and core-collapse supernovae (PDF) (Doctoral thesis). University of Basel.

- S2CID 59020556.

- ^ Boleu, R.; Nilsson, S. G.; Sheline, R. K. (1972). "On the termination of the r-process and the synthesis of superheavy elements". .

- ^

ISBN 978-0226109534, provides a clear technical introduction to these features. A more technical description can be found in Seeger, Fowler & Clayton 1965.

- ^ Figure 10 of Seeger, Fowler & Clayton 1965 shows this path of captures reaching magic neutron numbers 82 and 126 at smaller values of nuclear charge Z than it does along the stability path.

- .

- ^ Zagrebaev, V.; Karpov, A.; Greiner, W. (2013). "Future of superheavy element research: Which nuclei could be synthesized within the next few years?". .

- ^ Arcavi, I.; et al. (2017). "Optical emission from a kilonova following a gravitational-wave-detected neutron-star merger". .

- PMID 29094694.

- ^

Smartt, S. J.; et al. (2017). "A kilonova as the electromagnetic counterpart to a gravitational-wave source". PMID 29094693.

- S2CID 204837882.

- ^

Lattimer, J. M.; Schramm, D. N. (1974). "Black Hole–Neutron Star Collisions". doi:10.1086/181612.

- ^

Eichler, D.; Livio, M.; Piran, T.; Schramm, D. N. (1989). "Nucleosynthesis, neutrino bursts and gamma-rays from coalescing neutron stars". doi:10.1038/340126a0.

- ^

Freiburghaus, C.; Rosswog, S.; Thielemann, F.-K (1999). "r-process in Neutron Star Mergers". PMID 10525469.

- ^

Tanvir, N.; et al. (2013). "A 'kilonova' associated with the short-duration gamma-ray burst GRB 130603B". PMID 23912055.

- ^ "Neutron star mergers may create much of the universe's gold". Sid Perkins. Science AAAS. 20 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.