R. A. B. Mynors

Sir R. A. B. Mynors | |

|---|---|

Portrait by John William Thomas | |

| Born | Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors 28 July 1903 Langley Burrell, Wiltshire, England |

| Died | 17 October 1989 (aged 86) near Hereford, England |

| Spouse |

Lavinia Alington (m. 1945) |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor (1963) |

| Academic background | |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Classics |

| Institutions |

|

| Influenced |

|

Sir Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors

Mynors's career spanned most of the 20th century and straddled two of England's leading universities, Oxford and Cambridge. Educated at

Mynors held a reputation as one of Britain's foremost classicists.

Early life and secondary education

Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors was born in

Mynors attended

Academic career

Balliol College, Oxford

In 1922, Mynors won the Domus

His tenure at

In 1936, towards the end of his tenure at Balliol, Mynors met Eduard Fraenkel, then holder of a chair in Latin at Oxford. Having relocated to England because of the increasing discrimination against German Jews, Fraenkel was a leading exponent of Germany's scholarly tradition. His mentorship contributed to Mynors's transformation from amateur scholar to a professional critic of Latin texts. They maintained a close friendship, which exposed Mynors to other German philologists, including Rudolf Pfeiffer and Otto Skutsch.[11]

Mynors spent the winter of 1938 as a visiting scholar at

Pembroke College, Cambridge

In 1944, encouraged by Fraenkel,[13] Mynors took up an offer to assume the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at the University of Cambridge.[14] He also became a fellow of Pembroke College. In 1945,[2] shortly after moving to Cambridge, he married Lavinia Alington, a medical researcher[15] and daughter of his former teacher and Eton headmaster, Cyril Alington. The couple had no children.[16] The move to Cambridge meant an advancement of his academic career, but he soon came to contemplate a return to Oxford.[17] He applied unsuccessfully to become master of Balliol College after the position had been vacated by Sandie Lindsay in 1949. The historian David Keir was elected in his stead.[2]

His post at Cambridge caused changes to Mynors's profile as an academic. His duties at Balliol had centred on the supervision of undergraduates, while he was free to focus on palaeographical topics in his research. At Cambridge, Mynors was required to lecture extensively on Latin literature and to supervise research students, a task of which he had little experience. The duties of his university post left little time to get involved in the activities of the college, which led Mynors to regret his departure from Oxford, going so far as to describe the decision as a "fundamental error" in a personal letter.[17]

Although his post was chiefly that of a Latinist, his involvement in the publication of medieval texts intensified during the 1940s. After he was approached by V. H. Galbraith, a historian of the Middle Ages, Mynors became an editor on Nelson's Medieval Texts series in 1946. Working on the series first as a joint editor, and from 1962 as an advisory editor, he edited the Latin text for a number of volumes.[18] He was the principal author of editions of Walter Map's De nugis curialium and of Bede's Ecclesiastical History.[19] In 1947, he collaborated with the Oxford historian Alfred Brotherston Emden, who consulted Mynors for his own work on the history of the University of Oxford while assisting, in turn, with the Balliol catalogue.[20]

Corpus Christi College, Oxford

In 1953, Mynors was appointed

Retirement and death

In 1970, Mynors retired from his teaching duties and relocated to his estate at Treago Castle. In addition to an intense dedication to

On 17 October 1989, Mynors was killed in a road accident outside Hereford on his way back from a day working on the cathedral's manuscripts.[2] He was buried at St Weonards.[2] Meryl Jancey, the cathedral's Honorary Archivist, later revealed that Mynors had on the same day expressed his delight about his own scholarly work on the death of Bede: "He told me he was glad that he had translated for the Oxford Medieval Texts the account of Bede's death, and that Bede had not ceased in what he saw as his work for God until the very end."[25]

Contributions to scholarship

Cataloguing manuscripts

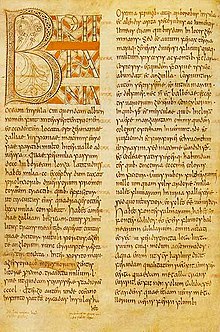

Mynors's chief interest lay in palaeography, the study of pre-modern manuscripts. He is credited with unravelling a number of complex manuscript relationships in his catalogues of the Balliol and Durham Cathedral libraries.[16] He had particular interest in the physical state of manuscripts, including examining blots and rulings. For the Balliol archivist Bethany Hamblen, this interest typifies the importance Mynors gave to formal features when evaluating hand-written books.[26]

Critical editions

A series of critical editions on Latin authors constitutes the entirety of Mynors's purely classical scholarship.

The first of his critical editions is of the Institutiones of Cassiodorus, the first produced since 1679. In the introduction, Mynors offered new insights into the complex manuscript tradition without resolving the fundamental question of how the original text was expanded in later copies.

In 1958, Mynors published an edition of the poems of Catullus.

His edition of Pliny's Epistulae employed a similar method but aimed to be an intermediate step rather than an overhaul of the text.[34] Mynors's edition of the complete works of Vergil revamped the text constructed by F. A. Hirtzel in 1900 which had become outdated.[35] He enlarged the manuscript base by drawing on 13 minor witnesses from the ninth century[36] and added an index of personal names.[37] Its judgement of these minor manuscripts, in particular, is described by the Latinist W. S. Maguinness as the edition's strength.[36] Given the incomplete state of the Aeneid, Vergil's epic poem on the wanderings of Aeneas, Mynors departed from his cautious editorial stance by printing a small number of modern conjectures.[38]

Mynors established a new text of Bede's Ecclesiastical History for the edition he published together with the historian Bertram Colgrave. His edition of this text followed that of Charles Plummer published in 1896. Collation of the Saint Petersburg Bede, an 8th-century manuscript unknown to Plummer, allowed Mynors to construct a new version of the M tradition.[39] Although he did not append a detailed critical apparatus and exegetical notes, his analysis of the textual history was praised by the Church historian Gerald Bonner as "lucid" and "excellently done".[40] Mynors himself considered the edition superficial and felt that its publication had been premature.[41] Winterbottom voices a similar opinion, writing that the text "hardly differ[ed] from Plummer's".[41]

Commentary on the Georgics

His scholarly legacy was enhanced by his posthumously published commentary on Vergil's Georgics. A comprehensive guide to Vergil's didactic poem on agriculture, the commentary has been lauded for its meticulous attention to technical detail and for Mynors's profound knowledge of agricultural practice.[42][43] In spite of its accomplishments, the classicist Patricia Johnston has noted that the commentary fails to engage seriously with contemporary scholarship on the text,[43] such as the tension between optimistic and pessimistic[c] readings.[23] In this regard, Mynors's last work reflects his lifelong scepticism towards literary criticism of any persuasion.[23]

Legacy

During his career, Mynors gained a reputation as "one of the leading classical scholars of his generation".[16] He drew praise from the scholarly community for his textual work. The Latinist Harold Gotoff states that he was an "extraordinary scholar",[3] while Winterbottom describes his critical editions as "distinguished".[44] His Oxford editions of the poets Catullus and Vergil in particular are singled out by Gotoff as "excellent";[3] they still serve as the standard editions of their texts in the early 21st century.[45]

Honours

Mynors was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1944 and made a Knight Bachelor in 1963. He was granted honorary fellowships by Balliol College, Oxford (1963), Pembroke College, Cambridge (1965), and Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1970). The Warburg Institute honoured him in the same way.[2] Mynors was also an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the Istituto Nazionale di Studi Romani (it). He held honorary degrees from the universities of Cambridge, Durham, Edinburgh, Sheffield, and Toronto.[46] In 1983, on his 80th birthday, Mynors's service to the study of Latin texts was honoured by the publication of Texts and Transmission: A Survey of the Latin Classics, edited by the Oxford Latinist L. D. Reynolds.[16] In 2020, an exhibition was held at Balliol to commemorate his scholarship on the college library.[47]

Publications

The following books were authored by Mynors:[48]

- Cassiodori Senatoris Institutiones. Clarendon Press. 1937. OCLC 3828537.

- Durham Cathedral Manuscripts to the End of the Twelfth Century. OCLC 7605487.

- C. Valerii Catulli Carmina (Reprinted ed.). Oxford University Press. 1958. ISBN 978-0-19-814604-9.

- Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Balliol College (Reprinted ed.). Oxford University Press. 1963. ISBN 978-0-19-818117-0.

- C. Plini Caecili Secundi: Epistularum Libri Decem (Reprinted ed.). Clarendon Press. 1963. ISBN 978-0-19-814643-8.

- XII Panegyrici Latini (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1964. ISBN 978-0-19-814647-6.

- Bede: Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Edited with ISBN 978-0-19-822202-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link - P. Vergili Maronis Opera. Clarendon Press. 1969. ISBN 978-0-19-814653-7.

- Walter Map: De Nugis Curialium. Courtiers' Trifles. Edited and translated by M. R. James. Revised with ISBN 978-0-19-822236-1.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link - Virgil, Georgics. Oxford University Press. 1990. ISBN 978-0-19-814978-1.

Notes

- ^ Transmission refers to the ways in which classical texts were circulated and preserved prior to the invention of printing.

- ^ Emendation occurs when a textual critic replaces the transmitted text with a supplement of his or her own creation.

- ^ In scholarship of Vergil, 'pessimism' describes readings of his poetry discerning a dark, downbeat outlook. The opposite view is termed 'optimism'.

References

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Nisbet 2004.

- ^ a b c d Gotoff 1991, p. 309.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 371.

- ^ a b Winterbottom 1993, p. 393.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Hamblen 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 375.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 377–380.

- ^ Gotoff 1991, pp. 310–311.

- ^ a b Winterbottom 1993, p. 381.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 382.

- ^ Gotoff 1991, p. 310.

- ^ Hamblen 2020, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sir Roger Mynors, Obituary". The Times. No. 63529. 19 October 1989. p. 16.

- ^ a b Winterbottom 1993, p. 383.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 384–388.

- ^ Hamblen 2020, p. 22.

- ^ a b Gotoff 1991, p. 311.

- ^ Hamblen 2020, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Winterbottom 1993, p. 396.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 395.

- ^ Hamblen 2020, p. 6.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 391.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Gaselee 1937, p. 189.

- ^ Souter 1937, p. 195.

- ^ a b Oliver 1959, p. 51.

- ^ Levine 1959, p. 416.

- ^ a b Harrison 2000, p. 67.

- ^ Fuchs 1966, p. 89.

- ^ Sewter 1970, p. 105.

- ^ a b Maguinness 1971, p. 198.

- ^ Maguinness 1971, p. 200.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 392.

- ^ Gatch 1970, p. 543.

- ^ Bonner 1970, p. 133.

- ^ a b Winterbottom 1993, p. 386.

- ^ Williams 1992, p. 89.

- ^ a b Johnston 1991.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, p. 389.

- ^ Trappes-Lomax 2007, p. 2.

- New York Times. 21 October 1989. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Hamblen 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Winterbottom 1993, pp. 400–401.

Bibliography

- Bonner, Gerald (1970). "Review of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Edited by Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors". ISSN 1469-7637.

- Fuchs, J. W. (1966). "Review of R. A. B. Mynors C. Caecilii Plinii Secundi Epistularum libri decem". ISSN 1568-525X.

- S2CID 162322683.

- Gatch, Milton (1970). "Review of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Edited by Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors". S2CID 161140635.

- Gotoff, Harold C. (1991). "Sir Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors (July 28, 1903 – October 17, 1989)". JSTOR 987037.

- Hamblen, Bethany (2020). 'Messing about with Manuscripts.' R. A. B. Mynors and Balliol's Medieval Library (PDF). Oxford: ISBN 978-1-83853-552-0.

- ISBN 978-3-89590-095-2.

- Johnston, Patricia (1991). "Review of Virgil, Georgics, Edited with a Commentary by R. A. B. Mynors, with a Preface by R. G. M. Nisbet". ISSN 1055-7660.

- Levine, Philip (1959). "Review of C. Valerii Catulli Carmina by R. A. B. Mynors" (PDF). JSTOR 292181.

- Maguinness, W. S. (1971). "A New Text of Virgil". S2CID 161190954.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39814. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- JSTOR 266211.

- Sewter, E. R. A. (1970). "Brief Reviews" (PDF). S2CID 248518852.

- JSTOR 23956521.

- Trappes-Lomax, John M. (2007). Catullus: A Textual Reappraisal. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-1-905125-15-9.

- Williams, Gordon (1992). "Virgil: Georgics". JSTOR 23040995.

- ISSN 0068-1202.