Rail transport

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails.[1] Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to road transport. It is used for about 8% of passenger and freight transport globally,[2] thanks to its energy efficiency[2] and potentially high speed.

| Part of a series on |

| Rail transport |

|---|

|

|

|

| Infrastructure |

|

|

| Service and rolling stock |

|

| Special systems |

|

|

| Miscellanea |

|

|

Rolling stock on rails generally encounters lower frictional resistance than rubber-tyred road vehicles, allowing rail cars to be coupled into longer trains. Power is usually provided by diesel or electrical locomotives. While railway transport is capital-intensive and less flexible than road transport, it can carry heavy loads of passengers and cargo with greater energy efficiency and safety.[a]

Precursors of railways driven by human or animal power have existed since antiquity, but modern rail transport began with the invention of the

In the 1880s,

History

Smooth, durable

For example, evidence indicates that a 6 to 8.5 km long Diolkos paved trackway transported boats across the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece from around 600 BC. The Diolkos was in use for over 650 years, until at least the 1st century AD.[3] Paved trackways were also later built in Roman Egypt.[4]

Pre-steam modern systems

Wooden rails introduced

In 1515,

Wagonways (or tramways) using wooden rails, hauled by horses, started appearing in the 1550s to facilitate the transport of ore tubs to and from mines and soon became popular in Europe. Such an operation was illustrated in Germany in 1556 by Georgius Agricola in his work De re metallica.[7] This line used "Hund" carts with unflanged wheels running on wooden planks and a vertical pin on the truck fitting into the gap between the planks to keep it going the right way. The miners called the wagons Hunde ("dogs") from the noise they made on the tracks.[8]

There are many references to their use in central Europe in the 16th century.[9] Such a transport system was later used by German miners at Caldbeck, Cumbria, England, perhaps from the 1560s.[10] A wagonway was built at Prescot, near Liverpool, sometime around 1600, possibly as early as 1594. Owned by Philip Layton, the line carried coal from a pit near Prescot Hall to a terminus about one-half mile (800 m) away.[11] A funicular railway was also made at Broseley in Shropshire some time before 1604. This carried coal for James Clifford from his mines down to the River Severn to be loaded onto barges and carried to riverside towns.[12] The Wollaton Wagonway, completed in 1604 by Huntingdon Beaumont, has sometimes erroneously been cited as the earliest British railway. It ran from Strelley to Wollaton near Nottingham.[13]

The Middleton Railway in Leeds, which was built in 1758, later became the world's oldest operational railway (other than funiculars), albeit now in an upgraded form. In 1764, the first railway in the Americas was built in Lewiston, New York.[14]

Metal rails introduced

In the late 1760s, the

A system was introduced in which unflanged wheels ran on L-shaped metal plates, which came to be known as plateways. John Curr, a Sheffield colliery manager, invented this flanged rail in 1787, though the exact date of this is disputed. The plate rail was taken up by Benjamin Outram for wagonways serving his canals, manufacturing them at his Butterley ironworks. In 1803, William Jessop opened the Surrey Iron Railway, a double track plateway, erroneously sometimes cited as world's first public railway, in south London.[16]

These two systems of constructing iron railways, the "L" plate-rail and the smooth edge-rail, continued to exist side by side until well into the early 19th century. The flanged wheel and edge-rail eventually proved its superiority and became the standard for railways.

Cast iron used in rails proved unsatisfactory because it was brittle and broke under heavy loads. The wrought iron invented by John Birkinshaw in 1820 replaced cast iron. Wrought iron, usually simply referred to as "iron", was a ductile material that could undergo considerable deformation before breaking, making it more suitable for iron rails. But iron was expensive to produce until Henry Cort patented the puddling process in 1784. In 1783 Cort also patented the rolling process, which was 15 times faster at consolidating and shaping iron than hammering.[17] These processes greatly lowered the cost of producing iron and rails. The next important development in iron production was hot blast developed by James Beaumont Neilson (patented 1828), which considerably reduced the amount of coke (fuel) or charcoal needed to produce pig iron.[18] Wrought iron was a soft material that contained slag or dross. The softness and dross tended to make iron rails distort and delaminate and they lasted less than 10 years. Sometimes they lasted as little as one year under high traffic. All these developments in the production of iron eventually led to the replacement of composite wood/iron rails with superior all-iron rails. The introduction of the Bessemer process, enabling steel to be made inexpensively, led to the era of great expansion of railways that began in the late 1860s. Steel rails lasted several times longer than iron.[19][20][21] Steel rails made heavier locomotives possible, allowing for longer trains and improving the productivity of railroads.[22] The Bessemer process introduced nitrogen into the steel, which caused the steel to become brittle with age. The open hearth furnace began to replace the Bessemer process near the end of the 19th century, improving the quality of steel and further reducing costs. Thus steel completely replaced the use of iron in rails, becoming standard for all railways.

The first passenger horsecar or tram, Swansea and Mumbles Railway was opened between Swansea and Mumbles in Wales in 1807.[23] Horses remained the preferable mode for tram transport even after the arrival of steam engines until the end of the 19th century, because they were cleaner compared to steam-driven trams which caused smoke in city streets.

Steam power introduced

In 1784 James Watt, a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer, patented a design for a steam locomotive. Watt had improved the steam engine of Thomas Newcomen, hitherto used to pump water out of mines, and developed a reciprocating engine in 1769 capable of powering a wheel. This was a large stationary engine, powering cotton mills and a variety of machinery; the state of boiler technology necessitated the use of low-pressure steam acting upon a vacuum in the cylinder, which required a separate condenser and an air pump. Nevertheless, as the construction of boilers improved, Watt investigated the use of high-pressure steam acting directly upon a piston, raising the possibility of a smaller engine that might be used to power a vehicle. Following his patent, Watt's employee William Murdoch produced a working model of a self-propelled steam carriage in that year.[24]

The first full-scale working railway steam locomotive was built in the United Kingdom in 1804 by Richard Trevithick, a British engineer born in Cornwall. This used high-pressure steam to drive the engine by one power stroke. The transmission system employed a large flywheel to even out the action of the piston rod. On 21 February 1804, the world's first steam-powered railway journey took place when Trevithick's unnamed steam locomotive hauled a train along the tramway of the Penydarren ironworks, near Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales.[25][26] Trevithick later demonstrated a locomotive operating upon a piece of circular rail track in Bloomsbury, London, the Catch Me Who Can, but never got beyond the experimental stage with railway locomotives, not least because his engines were too heavy for the cast-iron plateway track then in use.[27]

The first commercially successful steam locomotive was

This was followed in 1813 by the locomotive

In 1814

Steam power continued to be the dominant power system in railways around the world for more than a century.

Electric power introduced

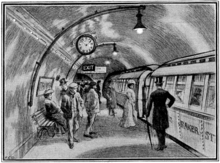

The first use of electrification on a main line was on a four-mile section of the Baltimore Belt Line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) in 1895 connecting the main portion of the B&O to the new line to New York through a series of tunnels around the edges of Baltimore's downtown. Electricity quickly became the power supply of choice for subways, abetted by the Sprague's invention of multiple-unit train control in 1897. By the early 1900s most street railways were electrified.

The

The first practical

In 1894, Hungarian engineer Kálmán Kandó developed a new type 3-phase asynchronous electric drive motors and generators for electric locomotives. Kandó's early 1894 designs were first applied in a short three-phase AC tramway in Évian-les-Bains (France), which was constructed between 1896 and 1898.[39][40]

In 1896, Oerlikon installed the first commercial example of the system on the

Italian railways were the first in the world to introduce electric traction for the entire length of a main line rather than a short section. The 106 km Valtellina line was opened on 4 September 1902, designed by Kandó and a team from the Ganz works.[41][42] The electrical system was three-phase at 3 kV 15 Hz. In 1918,[43] Kandó invented and developed the rotary phase converter, enabling electric locomotives to use three-phase motors whilst supplied via a single overhead wire, carrying the simple industrial frequency (50 Hz) single phase AC of the high voltage national networks.[42]

An important contribution to the wider adoption of AC traction came from SNCF of France after World War II. The company conducted trials at AC 50 Hz, and established it as a standard. Following SNCF's successful trials, 50 Hz, now also called industrial frequency was adopted as standard for main-lines across the world.[44]

Diesel power introduced

Track consists of two parallel steel rails, anchored

Rail gauges are usually categorized as

The track guides the conical, flanged wheels, keeping the cars on the track without active steering and therefore allowing trains to be much longer than road vehicles. The rails and ties are usually placed on a foundation made of compressed earth on top of which is placed a bed of ballast to distribute the load from the ties and to prevent the track from buckling as the ground settles over time under the weight of the vehicles passing above.

The ballast also serves as a means of drainage. Some more modern track in special areas is attached directly without ballast. Track may be prefabricated or assembled in place. By

On curves, the outer rail may be at a higher level than the inner rail. This is called superelevation or

Points and switches – also known as

Spikes in wooden ties can loosen over time, but split and rotten ties may be individually replaced with new wooden ties or concrete substitutes. Concrete ties can also develop cracks or splits, and can also be replaced individually. Should the rails settle due to soil subsidence, they can be lifted by specialized machinery and additional ballast tamped under the ties to level the rails.

Periodically, ballast must be removed and replaced with clean ballast to ensure adequate drainage. Culverts and other passages for water must be kept clear lest water is impounded by the trackbed, causing landslips. Where trackbeds are placed along rivers, additional protection is usually placed to prevent streambank erosion during times of high water. Bridges require inspection and maintenance, since they are subject to large surges of stress in a short period of time when a heavy train crosses.

Gauge incompatibility

The use of different track gauges in different regions of the world, and sometimes within the same country, can impede the movement of passengers and freight. Often elaborate transfer mechanisms are installed where two lines of different gauge meet to facilitate movement across the break of gauge. Countries with multiple gauges in use, such as India and Australia, have invested heavily to unify their rail networks. China is developing a modernized Eurasian Land Bridge to move goods by rail to Western Europe.

Train inspection systems

The inspection of railway equipment is essential for the safe movement of trains. Many types of defect detectors are in use on the world's railroads. These devices use technologies that vary from a simplistic paddle and switch to infrared and laser scanning, and even ultrasonic audio analysis. Their use has avoided many rail accidents over the 70 years they have been used.

Signalling

The signalling process is traditionally carried out in a

Electrification

The electrification system provides electrical energy to the trains, so they can operate without a prime mover on board. This allows lower operating costs, but requires large capital investments along the lines. Mainline and tram systems normally have overhead wires, which hang from poles along the line. Grade-separated rapid transit sometimes use a ground third rail.

Power may be fed as direct (DC) or alternating current (AC). The most common DC voltages are 600 and 750 V for tram and rapid transit systems, and 1,500 and 3,000 V for mainlines. The two dominant AC systems are 15 kV and 25 kV.

Stations

Platforms are used to allow easy access to the trains, and are connected to each other via

Operations

Ownership

Since the 1980s, there has been an increasing trend to split up railway companies, with companies owning the rolling stock separated from those owning the infrastructure. This is particularly true in Europe, where this arrangement is required by the European Union. This has allowed open access by any train operator to any portion of the European railway network. In the UK, the railway track is state owned, with a public controlled body (Network Rail) running, maintaining and developing the track, while Train Operating Companies have run the trains since privatization in the 1990s.[59]

In the U.S., virtually all rail networks and infrastructure outside the

Financing

The main source of income for railway companies is from

Governments may choose to give subsidies to rail operation, since rail transport has fewer

Safety

Some trains travel faster than road vehicles. They are heavy and unable to deviate from the track, and have longer stopping distances. Possible accidents include derailment (jumping the track) and collisions with another train or a road vehicle, or with pedestrians at level crossings, which account for the majority of all rail accidents and casualties. To minimize the risk, the most important safety measures are strict operating rules, e.g. railway signalling, and gates or grade separation at crossings. Train whistles, bells, or horns warn of the presence of a train, while trackside signals maintain the distances between trains. Another method used to increase safety is the addition of platform screen doors to separate the platform from train tracks. These prevent unauthorised incursion on to the train tracks which can result in accidents that cause serious harm or death, as well as providing other benefits such as preventing litter build up on the tracks which can pose a fire risk.

On many high-speed inter-city networks, such as Japan's Shinkansen, the trains run on dedicated railway lines without any level crossings. This is an important element in the safety of the system as it effectively eliminates the potential for collision with automobiles, other vehicles, or pedestrians, and greatly reduces the probability of collision with other trains. Another benefit is that services on the inter-city network remain punctual.

Maintenance

As in any infrastructure asset, railways must keep up with periodic inspection and maintenance to minimise the effect of infrastructure failures that can disrupt freight revenue operations and passenger services. Because passengers are considered the most crucial cargo and usually operate at higher speeds, steeper grades, and higher capacity/frequency, their lines are especially important. Inspection practices include track geometry cars or walking inspection. Curve maintenance especially for transit services includes gauging, fastener tightening, and rail replacement.

Rail corrugation is a common issue with transit systems due to the high number of light-axle, wheel passages which result in grinding of the wheel/rail interface. Since maintenance may overlap with operations, maintenance windows (nighttime hours,

Unlike

Social, economical, and energetic aspects

Energy

Transport by rail is an

A typical modern wagon can hold up to 113 tonnes (125 short tons) of freight on two four-wheel

In addition, the presence of track guiding the wheels allows for very long trains to be pulled by one or a few engines and driven by a single operator, even around curves, which allows for economies of scale in both manpower and energy use; by contrast, in road transport, more than two articulations causes fishtailing and makes the vehicle unsafe.

Energy efficiency

Considering only the energy spent to move the means of transport, and using the example of the urban area of Lisbon, electric trains seem to be on average 20 times more efficient than automobiles for transportation of passengers, if we consider energy spent per passenger-distance with similar occupation ratios.[68] Considering an automobile with a consumption of around 6 L/100 km (47 mpg‑imp; 39 mpg‑US) of fuel, the average car in Europe has an occupancy of around 1.2 passengers per automobile (occupation ratio around 24%) and that one litre of fuel amounts to about 8.8 kWh (32 MJ), equating to an average of 441 Wh (1,590 kJ) per passenger-km. This compares to a modern train with an average occupancy of 20% and a consumption of about 8.5 kW⋅h/km (31 MJ/km; 13.7 kW⋅h/mi), equating to 21.5 Wh (77 kJ) per passenger-km, 20 times less than the automobile.

Usage

Due to these benefits, rail transport is a major form of passenger and freight transport in many countries.[67] It is ubiquitous in Europe, with an integrated network covering virtually the whole continent. In India, China, South Korea and Japan, many millions use trains as regular transport. In North America, freight rail transport is widespread and heavily used, but intercity passenger rail transport is relatively scarce outside the Northeast Corridor, due to increased preference of other modes, particularly automobiles and airplanes.[63][page needed][69] However, implementing new and improved ways such as making it easily accessible within neighborhoods can aid in reducing commuters from using private vehicles and airplanes.[70]

South Africa, northern Africa and Argentina have extensive rail networks, but some railways elsewhere in Africa and South America are isolated lines. Australia has a generally sparse network befitting its population density but has some areas with significant networks, especially in the southeast. In addition to the previously existing east–west transcontinental line in Australia, a line from north to south has been constructed. The highest railway in the world is the

Social and economic impact

Modernization

Historically, railways have been considered central to modernity and ideas of progress.[72] The process of modernization in the 19th century involved a transition from a spatially oriented world to a time-oriented world. Timekeeping became of heightened importance, resulting in clock towers for railway stations, clocks in public places, and pocket watches for railway workers and travellers. Trains followed exact schedules and never left early, whereas in the premodern era, passenger ships left whenever the captain had enough passengers. In the premodern era, local time was set at noon, when the sun was at its highest; this changed with the introduction of standard time zones. Printed timetables were a convenience for travellers, but more elaborate timetables, called train orders, were essential for train crews, the maintenance workers, the station personnel, and for the repair and maintenance crews. The structure of railway timetables were later adapted for different uses, such as schedules for buses, ferries, and airplanes, for radio and television programmes, for school schedules, and for factory time clocks.[73]

The invention of the electrical telegraph in the early 19th century also was crucial for the development and operation of railroad networks. If bad weather disrupted the system, telegraphers relayed immediate corrections and updates throughout the system. Additionally, most railroads were single-track, with sidings and signals to allow lower priority trains to be sidetracked and have scheduled meets.

Nation-building

Scholars have linked railroads to successful nation-building efforts by states.[74]

Model of corporate management

According to historian Henry Adams, a railroad network needed:

- the energies of a generation, for it required all the new machinery to be created – capital, banks, mines, furnaces, shops, power-houses, technical knowledge, mechanical population, together with a steady remodelling of social and political habits, ideas, and institutions to fit the new scale and suit the new conditions. The generation between 1865 and 1895 was already mortgaged to the railways, and no one knew it better than the generation itself.[75]

The impact can be examined through five aspects: shipping, finance, management, careers, and popular reaction.

Shipping freight and passengers

Railroads form an efficient network for shipping freight and passengers across a large national market; their development thus was beneficial to many aspects of a nation's economy, including manufacturing, retail and wholesale, agriculture, and finance. By the 1940s, the United States had an integrated national market comparable in size to that of Europe, but free of internal barriers or tariffs, and supported by a common language, financial system, and legal system.[76]

Financial system

Financing of railroads provided the basis for a dramatic expansion of the private (non-governmental) financial system. Construction of railroads was far more expensive than factories: in 1860, the combined total of railroad stocks and bonds was $1.8 billion; in 1897, it reached $10.6 billion (compared to a total national debt of $1.2 billion).[77]

Funding came from financiers in the Northeastern United States and from Europe, especially Britain.[78] About 10 percent of the funding came from the government, particularly in the form of land grants that were realized upon completion of a certain amount of trackage.[79] The emerging American financial system was based on railroad bonds, and by 1860, New York was the dominant financial market. The British invested heavily in railroads around the world, but nowhere more than in the United States; the total bond value reached about $3 billion by 1914. However, in 1914–1917, the British liquidated their American assets to pay for war supplies.[80][81]

Modern management

Railroad management designed complex systems that could handle far more complicated simultaneous relationships than those common in other industries at the time. Civil engineers became the senior management of railroads. The leading American innovators were the

Career paths

The development of railroads led to the emergence of private-sector careers for both blue-collar workers and white-collar workers. Railroading became a lifetime career for young men; women were almost never hired. A typical career path would see a young man hired at age 18 as a shop labourer, be promoted to skilled mechanic at age 24, brakemen at 25, freight conductor at 27, and passenger conductor at age 57. White-collar career paths likewise were delineated: educated young men started in clerical or statistical work and moved up to station agents or bureaucrats at the divisional or central headquarters, acquiring additional knowledge, experience, and human capital at each level. Being very hard to replace, they were virtually guaranteed permanent jobs and provided with insurance and medical care.

Hiring, firing, and wage rates were set not by foremen, but by central administrators, to minimize favouritism and personality conflicts. Everything was done by the book, whereby an increasingly complex set of rules dictated to everyone exactly what should be done in every circumstance, and exactly what their rank and pay would be. By the 1880s, career railroaders began retiring, and pension systems were invented for them.[83]

Transportation

Railways contribute to social vibrancy and economic competitiveness by transporting multitudes of customers and workers to

Military role

Rail transport can be important for military activity. During the 1860s, railways provided a means for rapid movement of troops and supplies during the American Civil War,[87] as well as in the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian Wars[88] Throughout the 20th century, rail was a key element of war plans for rapid military mobilization, allowing for the quick and efficient transport of large numbers of reservists to their mustering-points, and infantry soldiers to the front lines.[89] So-called strategic railways were or are constructed for a primarily military purpose. The Western Front in France during World War I required many trainloads of munitions a day.[90] Conversely, owing to their strategic value, rail yards and bridges in Germany and occupied France were major targets of Allied air raids during World War II.[91] Rail transport and infrastructure continues to play an important role in present-day conflicts like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where sabotage of railways in Belarus and in Russia also influenced the course of the war.

Positive impacts

Railways channel growth towards dense city

Negative impacts

There has also been some opposition to the development of railway networks. For instance, the arrival of railways and

Pollution

A 2018 study found that the opening of the

Modern rail as economic development indicator

European

Subsidies

In 2010, annual rail spending in China was ¥840 billion (US$173 billion in 2019), from 2014 to 2017 China had an annual target of ¥800 billion (US$164 billion in 2019) and planned to spend ¥3.5 trillion (US$30 trillion in 2019) over 2016–2020.[98]

The Indian Railways are subsidized by around ₹260 billion (US$5 billion in 2019), of which around 60% goes to commuter rail and short-haul trips.[99]

According to the 2017 European Railway Performance Index for intensity of use, quality of service and safety performance, the top tier European national rail systems consists of Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Austria, Sweden, and France.[101] Performance levels reveal a positive correlation between public cost and a given railway system's performance, and also reveal differences in the value that countries receive in return for their public cost. Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland capture relatively high value for their money, while Luxembourg, Belgium, Latvia, Slovakia, Portugal, Romania, and Bulgaria underperform relative to the average ratio of performance to cost among European countries.[101]

| Country | Subsidy in billions of Euros | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 17.0 | 2014[102] | |

| 13.2 | 2013[103] | |

| 8.1 | 2009[104] | |

| 5.8 | 2012[105] | |

| 5.1 | 2015[106] | |

| 4.5 | 2015[107] | |

| 3.4 | 2008[100] | |

| 2.5 | 2014[108] | |

| 2.3 | 2009[100] | |

| 1.7 | 2008[100] | |

| 1.6 | 2009[109] | |

| 1.4 | 2008[110] | |

| 0.91 | 2008[110] |

Russia

In 2016 Russian Railways received 94.9 billion roubles (around US$1.4 billion) from the government.[111]

North America

United States

In 2015, funding from the U.S. federal government for Amtrak was around US$1.4 billion.[112] By 2018, appropriated funding had increased to approximately US$1.9 billion.[113]

See also

- Derailment

- Environmental design in rail transportation

- History of transport

- International Union of Railways

- List of countries by rail transport network size

- List of countries by rail usage

- List of railroad-related periodicals

- List of railway companies

- List of railway industry occupations

- Passenger rail terminology

- Rail transport by country

- Mega project

- Mine railway

- Outline of rail transport

- Railway systems engineering

- Track gauge

- Highway dimension

Notes

- ^ According to [Norman Bradbury (November 2002). Face the facts on transport safety (PDF). Railwatch (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010.], railways are the safest on both a per-mile and per-hour basis, whereas air transport is safe only on a per-mile basis.

- ^ Heilmann evaluated both AC and DC electric transmission for his locomotives, but eventually settled on a design based on Thomas Edison's DC system.[37]

References

- ^ "Railroad | History, Invention, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 27 November 2023. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b IEA (2019). The Future of Rail. Paris: International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Lewis, M. J. T. (2001). "Railways in the Greek and Roman world" (PDF). In Guy, A.; Rees, J. (eds.). Early Railways. A Selection of Papers from the First International Early Railways Conference. pp. 8–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- JSTOR 3855873.

- ^ "Der Reiszug: Part 1 – Presentation". Funimag. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ Kriechbaum, Reinhard (15 May 2004). "Die große Reise auf den Berg". der Tagespost (in German). Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ Georgius Agricola (trans Hoover), De re metallica (1913), p. 156.

- OCLC 1591369.

- ^ Lewis, Early wooden railways, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Warren Allison, Samuel Murphy and Richard Smith, An Early Railway in the German Mines of Caldbeck in G. Boyes (ed.), Early Railways 4: Papers from the 4th International Early Railways Conference 2008 (Six Martlets, Sudbury, 2010), pp. 52–69.

- ISBN 978-1-84674-298-9.

- ^ Peter King, The First Shropshire Railways in G. Boyes (ed.), Early Railways 4: Papers from the 4th International Early Railways Conference 2008 (Six Martlets, Sudbury, 2010), pp. 70–84.

- ^ "Huntingdon Beaumont's Wollaton to Strelley Waggonway". Nottingham Hidden History. 30 July 2013. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-665-78347-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7195-5746-0.

- ^ "Surrey Iron Railway 200th – 26th July 2003". Early Railways. Stephenson Locomotive Society. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-521-09418-4.

- ^ Landes 1969, pp. 92

- ISBN 978-0-543-72474-8.

RECENT ECONOMIC CHANGES AND THEIR EFFECT ON DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH AND WELL BEING OF SOCIETY WELLS.

- ^ Grübler, Arnulf (1990). The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures: Dynamics of Evolution and Technological Change in Transport (PDF). Heidelberg and New York: Physica-Verlag. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-1148-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-27367-1.

- ^ "Early Days of Mumbles Railway". BBC. 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- ^ Gordon, W. J. (1910). Our Home Railways, volume one. London: Frederick Warne and Co. pp. 7–9.

- ^ "Richard Trevithick's steam locomotive". National Museum Wales. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Steam train anniversary begins". BBC. 21 February 2004. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

A south Wales town has begun months of celebrations to mark the 200th anniversary of the invention of the steam locomotive. Merthyr Tydfil was the location where, on 21 February 1804, Richard Trevithick took the world into the railway age when he set one of his high-pressure steam engines on a local iron master's tram rails

- ^ Hamilton Ellis (1968). The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. The Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 12.

- ^ "'Puffing Billy' locomotive | Science Museum Group Collection". collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Hamilton Ellis (1968). The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. The Hamlyn Publishing Group. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Ellis, Hamilton (1968). The Pictorial Encyclopedia of Railways. Hamlyn Publishing Group.

- ^ "First in the world: The making of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway". Science and Industry Museum. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-415-06042-4.

- ^ Gordon, William (1910). "The Underground Electric". Our Home Railways. Vol. 2. London: Frederick Warne and Co. p. 156.

- ^ Renzo Pocaterra, Treni, De Agostini, 2003

- ^

"Richmond Union Passenger Railway". IEEE History Center. Archived from the originalon 1 December 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ "A brief history of the Underground". Transport for London.gov.uk. 15 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Duffy (2003), pp. 39–41.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 129.

- ISBN 978-0-9665734-2-8.

Evian-les-Bains kando.

- ISBN 978-0-912404-04-2.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 120–121.

- ^ a b Hungarian Patent Office. "Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931)". mszh.hu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 137.

- ^ Duffy (2003), p. 273.

- ^ "Motive power for British Railways" (PDF), The Engineer, vol. 202, p. 254, 24 April 1956, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2014, retrieved 11 October 2017

- – via Haithi Trust,

A small double cylinder engine has been mounted upon a truck, which is worked on a temporary line of rails, in order to show the adaptation of a petroleum engine for locomotive purposes, on tramways

- ^ Diesel Railway Traction, vol. 17, 1963, p. 25,

In one sense a dock authority was the earliest user of an oil-engined locomotive, for it was at the Hull docks of the North Eastern Railway that the Priestman locomotive put in its short period of service in 1894

- ISBN 978-0-691-02776-0.

- ISBN 978-3-344-70767-5.

- ISBN 978-1-349-05013-0.

- ^ US 1154785, Lemp, Hermann, "Controlling mechanism for internal-combustion engines", issued 1915-09-28

- ISBN 978-0-89024-026-7.

- ^ STANDS4 LLC, 2020, TPH Archived 19 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, abbreviations.com, accessed 19 July 2020

- ^ a b c d e f American Railway Engineering and Maintenance of Way Association Committee 24 – Education and Training. (2003). Practical Guide to Railway Engineering. AREMA, 2nd Ed.

- ^ "Rail freight in the next decade: Potential for performance improvements?". Global Railway Review. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Environmental Issues". The Environmental Blog. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- OCLC 1133662497.

- S2CID 246043093.

- ^ "About Us". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014.

- ISSN 2227-7390.

- ^ "Shipping Tariffs | Old Dominion Freight Line". www.odfl.com. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "EU Technical Report 2007". Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ OCLC 209631579.

- ^ "Statistics database for transports". epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu (statistical database). Eurostat, European Commission. 20 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Vojtech Eksler, ed. (5 May 2013). "Intermediate report on the development of railway safety in the European Union 2013" (PDF). www.era.europa.eu (report). Safety Unit, European Railway Agency & European Union. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ American Association of Railroads. "Railroad Fuel Efficiency Sets New Record". Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ a b "What is Rail Transport? Definition of Rail Transport, Rail Transport Meaning". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Publicada por João Pimentel Ferreira. "Carro ou comboio?". Veraveritas.eu. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Public Transportation Ridership Statistics". American Public Transportation Association. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "New height of world's railway born in Tibet". Xinhua News Agency. 24 August 2005. Archived from the original on 13 September 2005. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ Schivelbusch, G. (1986) The Railway Journey: Industrialization and Perception of Time and Space in the 19th Century. Oxford: Berg.

- ^ Tony Judt, When the Facts Change: Essays 1995–2010 (2015) pp. 287–288.

- ISSN 0007-1234.

- ^ Adams, Henry (1918). "The Press (1868)". The Education of Henry Adams. p. 240. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- S2CID 154883188.

- ^ Edward C. Kirkland, Industry comes of age: Business, labor, and public policy, 1860–1897 (1961) pp. 52, 68–74.

- S2CID 154702721.

- ^ Kirkland, Industry comes of age (1961) pp. 57–68.

- S2CID 153714837.

- ^ Saul Engelbourg, The man who found the money: John Stewart Kennedy and the financing of the western railroads (1996).

- ^ Alfred D. Chandler and Stephen Salsbury. "The railroads: Innovators in modern business administration." in Bruce Mazlish, ed., The Railroad and the Space Program (MIT Press, 1965) pp. 127–162

- ISBN 9780691047003.

- ^ Hong Kong Information Services Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Hong Kong 2009

- S2CID 38806085.

- ISBN 978-1-4831-8916-1.[page needed]

- ^ Christopher R. Gabel, "Railroad Generalship: Foundations of Civil War Strategy" (Army Command And General Staff College, Combat Studies Inst, 1997) online Archived 7 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dennis E. Showalter, Railroads and Rifles: soldiers, technology, and the unification of Germany (1975).

- .

- ^ Denis Bishop and W. J. K. Davies, Railways and War Before 1918 (London: Blandford Press, 1972); Bishop and Davies, Railways and War Since 1917 (1974).

- ProQuest 1296644342.

- ^ Lewandowski, Krzysztof (December 2015). "New coefficients of rail transport usage" (PDF). International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology. 5 (6): 89–91. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Squires, G. Ed. (2002) Urban Sprawl: Causes, Consequences, & Policy Responses. The Urban Institute Press.

- ^ Puentes, R. (2008). A Bridge to Somewhere: Rethinking American Transportation for the 21st Century. Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Report: Blueprint for American Prosperity series report.

- .

- .

- ^ Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (1 July 2013). "Transportation Infrastructure and Country Attractiveness". Revue Analyse Financière. Paris. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "China plans to spend $115 billion on railways in 2017: Xinhua". Reuters. 4 January 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Govt defends fare hike, says rail subsidy burden was too heavy". The Times of India. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "ANNEX to Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 concerning the opening of the market for domestic passenger transport services by rail" (PDF) (Commission Staff Working Document: Impact Assessment). Brussels: European Commission. 2013. pp. 6, 44, 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2013.

2008 data is not provided for Italy, so 2007 data is used instead

- ^ a b "the 2017 European Railway Performance Index". Boston Consulting Group. 18 April 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "German Railway Financing" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Efficiency indicators of Railways in France" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015.

- ^ "The age of the train" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Facts and arguments in favour of Swiss public transport". p. 24. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

6.3 billion Swiss francs

- ^ "Spanish railways battle profit loss with more investment". 17 September 2015. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "GB rail industry financial information 2014–15" (PDF). 9 March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

£3.5 billion

- ^ "ProRail report 2015" (PDF). p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "The evolution of public funding to the rail sector in 5 European countries – a comparison" (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ a b "European rail study report" (PDF). pp. 44, 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2013.

Includes both "Railway subsidies" and "Public Service Obligations".

- ^ "Government support for Russian Railways". Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "FY15 Budget, Business Plan 2015" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations and Consolidated Financial Statements With Report of Independent Auditors" (PDF). Amtrak. 28 January 2019. p. 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

Sources

- Duffy, Michael C. (2003). Electric Railways 1880–1990. ISBN 978-0-85296-805-5.

Further reading

- Burton, Anthony. Railway Empire: How the British Gave Railways to the World (2018) excerpt

- Chant, Christopher. The world's railways: the history and development of rail transport (Chartwell Books, 2001).

- Faith, Nicholas. The World the Railways Made (2014) excerpt

- Freeman, Michael. "The Railway as Cultural Metaphor: 'What Kind of Railway History?' Revisited." Journal of Transport History 20.2 (1999): 160–167.

- Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita. Imperial Technology and 'Native'Agency: A Social History of Railways in Colonial India, 1850–1920 (Taylor & Francis, 2018).

- Nock, O. S. Railways then and now: a world history (1975) online

- Nock, O. S. World atlas of railways (1978) online

- Nock, O. S. 150 years of main line railways (1980) online

- Pirie, Gordon. "Tracking railway histories." Journal of Transport History 35.2 (2014): 242–248.

- Sawai, Minoru, ed. The Development of Railway Technology in East Asia in Comparative Perspective (#Sringer, 2017)

- Trains Magazine. The Historical Guide to North American Railroads (3rd ed. 2014)

- Wolmar, Christian. Blood, iron, and gold: How the railroads transformed the world (Public Affairs, 2011).