Rat

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

| Rats | |

|---|---|

| |

| Brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Mirorder: | Simplicidentata |

| Order: | Rodentia |

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed

Rats are typically distinguished from

Species and description

The best-known rat species are the black rat (Rattus rattus) and the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). This group, generally known as the Old World rats or true rats, originated in Asia. Rats are bigger than most Old World mice, which are their relatives, but seldom weigh over 500 grams (17+1⁄2 oz) in the wild.[2]

The term rat is also used in the names of other small

Male rats are called bucks; unmated females, does, pregnant or parent females, dams; and infants, kittens or pups. A group of rats is referred to as a mischief.[6]

The common species are opportunistic survivors and often live with and near

Wild rodents, including rats, can carry many different

Rats become sexually mature at age 6 weeks, but reach social maturity at about 5 to 6 months of age. The average lifespan of rats varies by species, but many only live about a year due to predation.[11]

The black and brown rats diverged from other Old World rats in the forests of Asia during the beginning of the Pleistocene.[12]

Rat tails

The characteristic long tail of most rodents is a feature that has been extensively studied in various rat species models, which suggest three primary functions of this structure:

Multiple studies have explored the thermoregulatory capacity of rodent tails by subjecting test organisms to varying levels of physical activity and quantifying

On the other hand, the tail's ability to function as a proprioceptive sensor and modulator has also been investigated. As aforementioned, the tail demonstrates a high degree of muscularization and subsequent

The characteristic tail of murids also displays a unique defense mechanism known as

As pets

Specially bred rats have been kept as pets at least since the late 19th century. Pet rats are typically variants of the species

Tamed rats are generally friendly and can be taught to perform selected behaviors.Selective breeding has brought about different color and marking varieties in rats. Genetic mutations have also created different fur types, such as rex and hairless. Congenital malformation in selective breeding have created the dumbo rat, a popular pet choice due to their low, saucer-shaped ears.[22] A breeding standard exists for rat fanciers wishing to breed and show their rat at a rat show.[23]

As subjects for scientific research

In 1895,

The

The rat's larynx has been used in experimentations that involve inhalation toxicity, allograft rejection, and irradiation responses. One experiment described four features of the rat's larynx. The first being the location and attachments of the thyroarytenoid muscle, the alar cricoarytenoid muscle, and the superior cricoarytenoid muscle, the other of the newly named muscle that ran from the arytenoid to a midline tubercle on the cricoid. The newly named muscles were not seen in the human larynx. In addition, the location and configuration of the laryngeal alar cartilage was described. The second feature was that the way the newly named muscles appear to be familiar to those in the human larynx. The third feature was that a clear understanding of how MEPs are distributed in each of the laryngeal muscles was helpful in understanding the effects of botulinum toxin injection. The MEPs in the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle, lateral cricoarytenoid muscle, cricothyroid muscle, and superior cricoarytenoid muscle were focused mostly at the midbelly. In addition, the medial thyroarytenoid muscle were focused at the midbelly while the lateral thyroarytenoid muscle MEPs were focused at the anterior third of the belly. The fourth and final feature that was cleared up was how the MEPs were distributed in the thyroarytenoid muscle.[29]

Laboratory rats have also proved valuable in psychological studies of learning and other mental processes (Barnett 2002), as well as to understand

Domestic rats differ from wild rats in many ways. They are calmer and less likely to bite; they can tolerate greater crowding; they breed earlier and produce more offspring; and their brains, livers, kidneys, adrenal glands, and hearts are smaller (Barnett 2002).

Entirely new

General intelligence

Early studies found evidence both for and against measurable intelligence using the "g factor" in rats.[37][38] Part of the difficulty of understanding animal cognition, generally, is determining what to measure.[39] One aspect of intelligence is the ability to learn, which can be measured using a maze like the T-maze.[39] Experiments done in the 1920s showed that some rats performed better than others in maze tests, and if these rats were selectively bred, their offspring also performed better, suggesting that in rats an ability to learn was heritable in some way.[39]

As food

Rat meat is a food that, while

Working rats

Rats have been used as working animals. Tasks for working rats include the sniffing of gunpowder residue,

As pests

Rats have long been considered deadly pests. Once considered a modern myth, the

Most urban areas battle rat infestations. A 2015 study by the

Chicago was declared the "rattiest city" in the US by the pest control company Orkin in 2020, for the sixth consecutive time. It's followed by Los Angeles, New York, Washington, DC, and San Francisco.[49] To help combat the problem, a Chicago animal shelter has placed more than 1000 feral cats (sterilized and vaccinated) outside of homes and businesses since 2012, where they hunt and catch rats while also providing a deterrent simply by their presence.[50]

Rats have the ability to swim up sewer pipes into toilets.[51][52] Rats will infest any area that provides shelter and easy access to sources of food and water, including under sinks, near garbage, and inside walls or cabinets.[53]

In the spread of disease

Rats can serve as

Rats are also associated with human

As invasive species

When introduced into locations where rats previously did not exist, they can wreak an enormous degree of

The ship or wharf rat has contributed to the extinction of many species of wildlife, including birds, small mammals, reptiles, invertebrates, and plants, especially on islands. True rats are omnivorous, capable of eating a wide range of plant and animal foods, and have a very high birth rate. When introduced to a new area, they quickly reproduce to take advantage of the new food supply. In particular, they prey on the eggs and young of forest birds, which on isolated islands often have no other predators and thus have no fear of predators.[61] Some experts believe that rats are to blame for between forty percent and sixty percent of all seabird and reptile extinctions, with ninety percent of those occurring on islands. Thus man has indirectly caused the extinction of many species by accidentally introducing rats to new areas.[62]

Rat-free areas

Rats are found in nearly all areas of Earth which are inhabited by human beings. The only rat-free continent is

As part of

In January 2015, an international "Rat Team" set sail from the

The Canadian province of Alberta is notable for being the largest inhabited area on Earth which is free of true rats due to very aggressive government rat control policies. It has large numbers of native pack rats, also called bushy-tailed wood rats, but they are forest-dwelling vegetarians which are much less destructive than true rats.[70]

Alberta was settled relatively late in North American history and only became a province in 1905. Black rats cannot survive in its climate at all, and brown rats must live near people and in their structures to survive the winters. There are numerous predators in Canada's vast natural areas which will eat non-native rats, so it took until 1950 for invading rats to make their way over land from Eastern Canada.[71] Immediately upon their arrival at the eastern border with Saskatchewan, the Alberta government implemented an extremely aggressive rat control program to stop them from advancing further. A systematic detection and eradication system was used throughout a control zone about 600 kilometres (400 mi) long and 30 kilometres (20 mi) wide along the eastern border to eliminate rat infestations before the rats could spread further into the province. Shotguns, bulldozers, high explosives, poison gas, and incendiaries were used to destroy rats. Numerous farm buildings were destroyed in the process. Initially, tons of arsenic trioxide were spread around thousands of farm yards to poison rats, but soon after the program commenced the rodenticide and medical drug warfarin was introduced, which is much safer for people and more effective at killing rats than arsenic.[72]

Forceful government control measures, strong public support and enthusiastic citizen participation continue to keep rat infestations to a minimum.[73] The effectiveness has been aided by a similar but newer program in Saskatchewan which prevents rats from even reaching the Alberta border. Alberta still employs an armed rat patrol to control rats along Alberta's borders. About ten single rats are found and killed per year, and occasionally a large localized infestation has to be dug out with heavy machinery, but the number of permanent rat infestations is zero.[74]

In culture

On the Isle of Man, there is a taboo against the word "rat".[76]

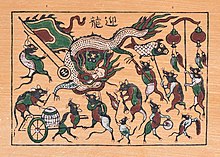

Asian cultures

The rat (sometimes referred to as a mouse) is the first of the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. People born in this year are expected to possess qualities associated with rats, including creativity, intelligence, honesty, generosity, ambition, a quick temper and wastefulness. People born in a year of the rat are said to get along well with "monkeys" and "dragons", and to get along poorly with "horses".

In Indian tradition, rats are seen as the vehicle of

European cultures

European associations with the rat are generally negative. For instance, "Rats!" is used as a substitute for various vulgar

Rats are often used in scientific experiments; animal rights activists allege the treatment of rats in this context is cruel. The term "lab rat" is used, typically in a self-effacing manner, to describe a person whose job function requires them to spend a majority of their work time engaged in bench-level research (such as postgraduate students in the sciences).

Terminology

Rats are frequently blamed for damaging food supplies and other goods, or spreading disease. Their reputation has carried into common parlance: in the

Among trade unions, the word "rat" is also a term for nonunion employers or breakers of union contracts, and this is why unions use inflatable rats.[78]

Fiction

Depictions of rats in fiction are historically inaccurate and negative. The most common falsehood is the squeaking almost always heard in otherwise realistic portrayals (i.e. non

The actual portrayals of rats vary from negative to positive with a majority in the negative and ambiguous..

Selfish helpfulness —those willing to help for a price— has also been attributed to fictional rats.[79] Templeton, from E. B. White's Charlotte's Web, repeatedly reminds the other characters that he is only involved because it means more food for him, and the cellar-rat of John Masefield's The Midnight Folk requires bribery to be of any assistance.

By contrast, the rats appearing in the Doctor Dolittle books tend to be highly positive and likeable characters, many of whom tell their remarkable life stories in the Mouse and Rat Club established by the animal-loving doctor.

Some fictional works use rats as the main characters. Notable examples include the society created by O'Brien's

In

Wererats,

The Pied Piper

One of the oldest and most historic stories about rats is "

See also

References

- ^ "Rat Fact Sheet". Nature. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- ^ "Habits, Habitat & Types of Mice". Live Science. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ a b Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Chicago, IL: Britannica Digital Learning. 2017 – via Credo Reference.

- ^ "Bandicota Gray, 1873". www.gbif.org. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "ITIS - Report: Bandicota bengalensis". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "Creature Feature Rats". ABC.net.au. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- PMID 19206089. Archived from the originalon 2012-12-17.

- .

- S2CID 205694138.

- PMID 4321688.

- ^ "How old is a rat in human years?". RatBehavior.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- PMID 22073158.

- ^ "Rat Tails". Rat Behavior and Biology. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ Grant, Karen. "Degloving Injury". Rat Health Guide. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- PMID 28814636.

- PMID 27227066.

- S2CID 40356618.

- PMID 20729800.

- ^ Milcheski, Dimas (2012). "Development of an experimental model of degloving injury in rats". Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 27: 514–17.

- ^ "Wild Rats in Captivity and Domestic Rats in the Wild". Ratbehaviour.org. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ "Merk Veterinary Manual Global Zoonoses Table". Merckvetmanual.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-17. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- PMID 21637698.

- ^ "AFRMA OFFICIAL RAT STANDARD". American Fancy Rat & Mouse Association. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Rat - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2024-04-09.

- ^ Research, National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral (1988), "Benefits Derived from the Use of Animals", Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral Research, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 2024-04-09

- ^ PMID 20345858.

- from the original on 2017-08-18.

- PMID 20345858.

- S2CID 30325002.

- ^ "Why do we use rats?". Cambridge University. 28 October 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Ramsden, Edmund; Adams, Jon (January 2008). "Escaping the Laboratory: The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun & Their Cultural Influence" (PDF). Department of Economic History at London School of Economics. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- PMID 17346969. Archived from the originalon 3 July 2012.

- ^ "Rats Capable Of Reflecting On Mental Processes". Sciencedaily.com. 2007-03-09. Archived from the original on 2012-10-10. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Gibbs RA et al.: Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution.: Nature. 2004 April 1; 428(6982):475–6.

- ^ "Animal studies in psychology". American Psychological Association. January 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "Genome project". www.ensembl.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ^ Lashley, K., Brain Mechanisms and Intelligence, Dover Publications, New York, 1929/1963, 186 pp.

- ^ Thorndike, R (1935). "Organization of behavior in the albino rat". Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 17: 1–70.

- ^ PMID 28981308.

- ^ Newvision Archive (2005-03-10). "Rats for dinner, a delicacy to some, a taboo to many". Newvision.co.ug. Archived from the original on 2012-09-22. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "Video of Bart Weetjens talk on use of rats as odour detectors". Ted.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ "Massive plagues of rats swarm across India every fifty years". Io9.com. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ "The Black Plague". University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2013-03-01. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ Maev Kennedy (2011-08-17). "Black Death study lets rats off the hook". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ "CDC – Diseases directly transmitted by rodents – Rodents". Centers for Disease Control. 2011-06-07. Archived from the original on 2013-03-17. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ Clark, Patrick (2017-01-17). "The Most Vermin-Infested American Cities". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- ^ Wilsey, Sean (2005-03-17). "Sean Wilsey reviews 'Rats' by Robert Sullivan · LRB 17 March 2005". London Review of Books. Lrb.co.uk. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ "Questions and Answers Regarding New York State Pest Management Program". DOEC of NY State. Archived from the original on 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ^ "Rats! Chicago Tops Orkin's Rattiest Cities List for Sixth Consecutive Time". PR Newswire. 13 Oct 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Guzman, Joseph (11 May 2021). "1,000 feral cats released onto Chicago streets to tackle rat explosion". The Hill. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Klein, Stephanie (2014-10-17). "How to keep the rats from coming up through your toilet". Archived from the original on 2015-09-01. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ^ "See How Easily a Rat Can Wriggle Up Your Toilet". video.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 2015-08-21. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ^ "Identify and Prevent Rodent Infestations". epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ "Information on other rodent-related diseases – Leptospirosis Information". Leptospirosis Information. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ^ Mench, Chris (4 February 2022). "New York City's Rats Could Have Their Own Strain of COVID-19". Thrillist. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Watson, J. (2008). New building, old parasite: Mesostigmatid mites—an ever-present threat to barrier rodent facilities. ILAR journal, 49(3), 303–309.

- PMID 9868661.

- ^ "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ "Predation by exotic rats on Australian offshore islands of less than 1000 km2 (100,000 ha) listing advice" (PDF). Government of Australia. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "Species – Brown Rat". The Mammal Society. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "Rattus rattus (mammal)". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "Humans outdone by Rats for causing Extinctions". Science Avenger. 2007-12-05. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "Preventing the introduction of non-native species to Antarctica". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Rosen, Yereth (2009-06-13). "Hawadax Island Is Rat-Free". Reuters. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ Cooper, John (2022-12-13). "Pioneering rodent eradication in the sub-Antarctic: the Campbell Island Rat Eradication Project". Mouse-Free Marion. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "Eradication—The Clearance of Campbell Island". New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- JSTOR 24053177.

- ^ Guthrie, Kate (2020-03-22). "Rat eradication breakthrough — Breaksea Island 1988". Predator Free NZ Trust. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ Gill, First= Victoria (23 January 2015). "South Georgia rat eradication mission sets sail". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Bushy-Tailed Woodrat (Pack Rat)". Pest Control Canada. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "Rattus norvegicus (mammal) – Details of this species in Alberta". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "The History of Rat Control In Alberta". Alberta Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Rat Control in Alberta". Alberta Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Giovannetti, Justin (26 November 2015). "On the frontlines of Alberta's war against rats". Toronto Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "NATURE NOTES: Mus Maximus". www.wigantoday.net. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- ^ MacKinnon, J. B. (September 26, 2023). "In Defense of the Rat". hakaimagazine.com. Hakai Magazine. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Nevada Journal: Louts and the Rat World". Nj.npri.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-19869-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7407-7179-8.

Remy, the earnest little rat who is its hero, is such a lovable, determined, gifted rodent that I want to know what happens to him next, now that he has conquered the summit of French cuisine.

- ^ ISBN 0-8803-8738-6.

- Paizo Publishing, 2003).

- ISBN 1-56504-428-2.

- ^ Fusco, Virginia (2015). Monstrous Figurations: Notes for a Feminist Reading (Tesis doctoral). Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. pp. 4, 122.

- ^ Kadushin, Raphael (3 September 2020). "The grim truth behind the Pied Piper". BBC Travel.

Further reading

- List of books and articles about rats, is a non-fiction list.

External links

- High-Resolution Images of the Rat Brain (archived 3 March 2016)

- National Bio Resource Project for the Rat in Japan (archived 29 April 2005)

- Rat Behaviour and Biology

- Rat Genome Database

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Rat". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Rat". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "