Precision and recall

In

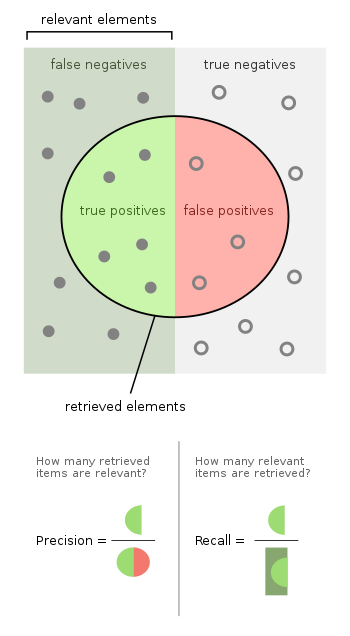

Precision (also called

Recall (also known as sensitivity) is the fraction of relevant instances that were retrieved. Written as a formula:

Both precision and recall are therefore based on relevance.

Consider a computer program for recognizing dogs (the relevant element) in a digital photograph. Upon processing a picture which contains ten cats and twelve dogs, the program identifies eight dogs. Of the eight elements identified as dogs, only five actually are dogs (true positives), while the other three are cats (false positives). Seven dogs were missed (false negatives), and seven cats were correctly excluded (true negatives). The program's precision is then 5/8 (true positives / selected elements) while its recall is 5/12 (true positives / relevant elements).

Adopting a

More generally, recall is simply the complement of the type II error rate (i.e., one minus the type II error rate). Precision is related to the type I error rate, but in a slightly more complicated way, as it also depends upon the

The above cat and dog example contained 8 − 5 = 3 type I errors (false positives) out of 10 total cats (true negatives), for a type I error rate of 3/10, and 12 − 5 = 7 type II errors (false negatives), for a type II error rate of 7/12. Precision can be seen as a measure of quality, and recall as a measure of quantity. Higher precision means that an algorithm returns more relevant results than irrelevant ones, and high recall means that an algorithm returns most of the relevant results (whether or not irrelevant ones are also returned).

Introduction

In a

Precision and recall are not particularly useful metrics when used in isolation. For instance, it is possible to have perfect recall by simply retrieving every single item. Likewise, it is possible to have near-perfect precision by selecting only a very small number of extremely likely items.

In a classification task, a precision score of 1.0 for a class C means that every item labelled as belonging to class C does indeed belong to class C (but says nothing about the number of items from class C that were not labelled correctly) whereas a recall of 1.0 means that every item from class C was labelled as belonging to class C (but says nothing about how many items from other classes were incorrectly also labelled as belonging to class C).

Often, there is an inverse relationship between precision and recall, where it is possible to increase one at the cost of reducing the other. Brain surgery provides an illustrative example of the tradeoff. Consider a brain surgeon removing a cancerous tumor from a patient's brain. The surgeon needs to remove all of the tumor cells since any remaining cancer cells will regenerate the tumor. Conversely, the surgeon must not remove healthy brain cells since that would leave the patient with impaired brain function. The surgeon may be more liberal in the area of the brain they remove to ensure they have extracted all the cancer cells. This decision increases recall but reduces precision. On the other hand, the surgeon may be more conservative in the brain cells they remove to ensure they extracts only cancer cells. This decision increases precision but reduces recall. That is to say, greater recall increases the chances of removing healthy cells (negative outcome) and increases the chances of removing all cancer cells (positive outcome). Greater precision decreases the chances of removing healthy cells (positive outcome) but also decreases the chances of removing all cancer cells (negative outcome).

Usually, precision and recall scores are not discussed in isolation. A precision-recall curve plots precision as a function of recall; usually precision will decrease as the recall increases. Alternatively, values for one measure can be compared for a fixed level at the other measure (e.g. precision at a recall level of 0.75) or both are combined into a single measure. Examples of measures that are a combination of precision and recall are the

Definition

For classification tasks, the terms true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives (see Type I and type II errors for definitions) compare the results of the classifier under test with trusted external judgments. The terms positive and negative refer to the classifier's prediction (sometimes known as the expectation), and the terms true and false refer to whether that prediction corresponds to the external judgment (sometimes known as the observation).

Let us define an experiment from P positive instances and N negative instances for some condition. The four outcomes can be formulated in a 2×2 contingency table or confusion matrix, as follows:

| Predicted condition | Sources: [4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] | ||||

| Total population = P + N |

Predicted Positive (PP) | Predicted Negative (PN) | Informedness, bookmaker informedness (BM) = TPR + TNR − 1 |

Prevalence threshold (PT) = √TPR × FPR - FPR/TPR - FPR | |

| Positive (P) [a] | False negative (FN), miss, underestimation |

power = TP/P = 1 − FNR |

type II error [c] = FN/P = 1 − TPR | ||

| Negative (N)[d] | False positive (FP),

false alarm, overestimation |

type I error [f] = FP/N = 1 − TNR |

specificity (SPC), selectivity = TN/N = 1 − FPR | ||

| Prevalence = P/P + N |

precision = TP/PP = 1 − FDR |

False omission rate (FOR) = FN/PN = 1 − NPV |

Positive likelihood ratio (LR+) = TPR/FPR |

Negative likelihood ratio (LR−) = FNR/TNR | |

| Accuracy (ACC) = TP + TN/P + N |

False discovery rate (FDR) = FP/PP = 1 − PPV |

Negative predictive value (NPV) = TN/PN = 1 − FOR |

Markedness (MK), deltaP (Δp) = PPV + NPV − 1 |

Diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) = LR+/LR− | |

| Balanced accuracy (BA) = TPR + TNR/2 |

F1 score = 2 PPV × TPR/PPV + TPR = 2 TP/2 TP + FP + FN |

Fowlkes–Mallows index (FM) = √PPV × TPR |

Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) = √TPR × TNR × PPV × NPV - √FNR × FPR × FOR × FDR |

Threat score (TS), critical success index (CSI), Jaccard index = TP/TP + FN + FP | |

- ^ the number of real positive cases in the data

- ^ A test result that correctly indicates the presence of a condition or characteristic

- ^ Type II error: A test result which wrongly indicates that a particular condition or attribute is absent

- ^ the number of real negative cases in the data

- ^ A test result that correctly indicates the absence of a condition or characteristic

- ^ Type I error: A test result which wrongly indicates that a particular condition or attribute is present

Precision and recall are then defined as:[13]

Recall in this context is also referred to as the true positive rate or

Precision vs. Recall

Both precision and recall may be useful in cases where there is imbalanced data. However, it may be valuable to prioritize one over the other in cases where the outcome of a false positive or false negative is costly. For example, in medical diagnosis, a false positive test can lead to unnecessary treatment and expenses. In this situation, it is useful to value precision over recall. In other cases, the cost of a false negative is high. For instance, the cost of a false negative in fraud detection is high, as failing to detect a fraudulent transaction can result in significant financial loss. [14]

Probabilistic Definition

Precision and recall can be interpreted as (estimated) conditional probabilities:[15] Precision is given by while recall is given by ,[16] where is the predicted class and is the actual class (i.e. means the actual class is positive). Both quantities are, therefore, connected by Bayes' theorem.

No-Skill Classifiers

The probabilistic interpretation allows to easily derive how a no-skill classifier would perform. A no-skill classifiers is defined by the property that the joint probability is just the product of the unconditional probabilites since the classification and the presence of the class are

For example the precision of a no-skill classifier is simply a constant i.e. determined by the probability/frequency with which the class P occurs.

A similar argument can be made for the recall: which is just (the typically threshold dependent) probability for a positive classification.

Some very specific no-skill classifiers are implemented in sklearn and are named dummy classifiers there.[17]

Imbalanced data

Accuracy can be a misleading metric for imbalanced data sets. Consider a sample with 95 negative and 5 positive values. Classifying all values as negative in this case gives 0.95 accuracy score. There are many metrics that don't suffer from this problem. For example, balanced accuracy[18] (bACC) normalizes true positive and true negative predictions by the number of positive and negative samples, respectively, and divides their sum by two:

For the previous example (95 negative and 5 positive samples), classifying all as negative gives 0.5 balanced accuracy score (the maximum bACC score is one), which is equivalent to the expected value of a random guess in a balanced data set. Balanced accuracy can serve as an overall performance metric for a model, whether or not the true labels are imbalanced in the data, assuming the cost of FN is the same as FP.

The TPR and FPR are a property of a given classifier operating at a specific threshold. However, the overall number of TPs, FPs etc depend on the class imbalance in the data via the class ratio . As the recall (or TPR) depends only on positive cases, it is not affected by , but the precision is. We have that

Thus the precision has an explicit dependence on .[19] Starting with balanced classes at and gradually decreasing , the corresponding precision will decrease, because the denominator increases.

Another metric is the predicted positive condition rate (PPCR), which identifies the percentage of the total population that is flagged. For example, for a search engine that returns 30 results (retrieved documents) out of 1,000,000 documents, the PPCR is 0.003%.

According to Saito and Rehmsmeier, precision-recall plots are more informative than ROC plots when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced data. In such scenarios, ROC plots may be visually deceptive with respect to conclusions about the reliability of classification performance.[20]

Different from the above approaches, if an imbalance scaling is applied directly by weighting the confusion matrix elements, the standard metrics definitions still apply even in the case of imbalanced datasets.[21] The weighting procedure relates the confusion matrix elements to the support set of each considered class.

F-measure

A measure that combines precision and recall is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, the traditional F-measure or balanced F-score:

This measure is approximately the average of the two when they are close, and is more generally the harmonic mean, which, for the case of two numbers, coincides with the square of the geometric mean divided by the arithmetic mean. There are several reasons that the F-score can be criticized, in particular circumstances, due to its bias as an evaluation metric.[1] This is also known as the measure, because recall and precision are evenly weighted.

It is a special case of the general measure (for non-negative real values of ):

Two other commonly used measures are the measure, which weights recall higher than precision, and the measure, which puts more emphasis on precision than recall.

The F-measure was derived by van Rijsbergen (1979) so that "measures the effectiveness of retrieval with respect to a user who attaches times as much importance to recall as precision". It is based on van Rijsbergen's effectiveness measure , the second term being the weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall with weights . Their relationship is where .

Limitations as goals

There are other parameters and strategies for performance metric of information retrieval system, such as the area under the

See also

- Uncertainty coefficient, also called proficiency

- Sensitivity and specificity

- Confusion matrix

- Scoring rule

- Base rate fallacy

References

- ^ a b c d Powers, David M W (2011). "Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F-Measure to ROC, Informedness, Markedness & Correlation" (PDF). Journal of Machine Learning Technologies. 2 (1): 37–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-11-14.

- S2CID 17104364.

- ^ Powers, David M. W. (2012). "The Problem with Kappa". Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL2012) Joint ROBUS-UNSUP Workshop.

- ^

Balayla, Jacques (2020). "Prevalence threshold (ϕe) and the geometry of screening curves". PLOS ONE. 15 (10): e0240215. PMID 33027310.

- ^

Fawcett, Tom (2006). "An Introduction to ROC Analysis" (PDF). Pattern Recognition Letters. 27 (8): 861–874. S2CID 2027090.

- ^

Piryonesi S. Madeh; El-Diraby Tamer E. (2020-03-01). "Data Analytics in Asset Management: Cost-Effective Prediction of the Pavement Condition Index". Journal of Infrastructure Systems. 26 (1): 04019036. S2CID 213782055.

- ^ Powers, David M. W. (2011). "Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F-Measure to ROC, Informedness, Markedness & Correlation". Journal of Machine Learning Technologies. 2 (1): 37–63.

- ^

Ting, Kai Ming (2011). Sammut, Claude; Webb, Geoffrey I. (eds.). Encyclopedia of machine learning. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-30164-8.

- ^ Brooks, Harold; Brown, Barb; Ebert, Beth; Ferro, Chris; Jolliffe, Ian; Koh, Tieh-Yong; Roebber, Paul; Stephenson, David (2015-01-26). "WWRP/WGNE Joint Working Group on Forecast Verification Research". Collaboration for Australian Weather and Climate Research. World Meteorological Organisation. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^

Chicco D, Jurman G (January 2020). "The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation". BMC Genomics. 21 (1): 6-1–6-13. PMID 31898477.

- ^

Chicco D, Toetsch N, Jurman G (February 2021). "The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is more reliable than balanced accuracy, bookmaker informedness, and markedness in two-class confusion matrix evaluation". BioData Mining. 14 (13): 13. PMID 33541410.

- ^ Tharwat A. (August 2018). "Classification assessment methods". Applied Computing and Informatics. 17: 168–192. .

- ^ ISBN 3-540-76916-1

- ^ https://www.v7labs.com/blog/precision-vs-recall-guide#accuracy-precision-or-recallwhen-to-use-what

- ^ Fatih Cakir, Kun He, Xide Xia, Brian Kulis, Stan Sclaroff, Deep Metric Learning to Rank, In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019.

- ISBN 978-3-031-02328-6.

- ^ "Sklearn.dummy.DummyClassifier".

- PMID 15826309.

- ISSN 0899-7667.

- PMID 25738806.

- Suzanne Ekelund (March 2017). "Precision-recall curves – what are they and how are they used?". Acute Care Testing.

- S2CID 225136860.

- ^ Zygmunt Zając. What you wanted to know about AUC. http://fastml.com/what-you-wanted-to-know-about-auc/

- Baeza-Yates, Ricardo; Ribeiro-Neto, Berthier (1999). Modern Information Retrieval. New York, NY: ACM Press, Addison-Wesley, Seiten 75 ff. ISBN 0-201-39829-X

- Hjørland, Birger (2010); The foundation of the concept of relevance, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(2), 217-237

- Makhoul, John; Kubala, Francis; Schwartz, Richard; and Weischedel, Ralph (1999); Performance measures for information extraction, in Proceedings of DARPA Broadcast News Workshop, Herndon, VA, February 1999

- van Rijsbergen, Cornelis Joost "Keith" (1979); Information Retrieval, London, GB; Boston, MA: Butterworth, 2nd Edition, ISBN 0-408-70929-4