Red-tailed hawk

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (January 2024) |

| Red-tailed hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Buteo |

| Species: | B. jamaicensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, 1788)

| |

| |

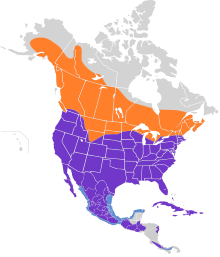

Breeding Year-round Nonbreeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Buteo borealis | |

The red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) is a

The 14 recognized subspecies vary in appearance and range, varying most often in color, and in the west of North America, red-tails are particularly often strongly polymorphic, with individuals ranging from almost white to nearly all black.[5] The subspecies Harlan's hawk (B. j. harlani) is sometimes considered a separate species (B. harlani).[6] The red-tailed hawk is one of the largest members of the genus Buteo, typically weighing from 690 to 1,600 g (1.5 to 3.5 lb) and measuring 45–65 cm (18–26 in) in length, with a wingspan from 110–141 cm (3 ft 7 in – 4 ft 8 in). This species displays sexual dimorphism in size, with females averaging about 25% heavier than males.[2][7]

The diet of red-tailed hawks is highly variable and reflects their status as opportunistic generalists, but in North America, they are most often predators of small mammals such as rodents of an immense diversity of families and species. Prey that is terrestrial and at least partially diurnal is preferred, so types such as ground squirrels are preferred where they naturally occur.[8] Over much of the range, smallish rodents such as voles alternated with larger rabbits and hares often collectively form the bulk of the diet. Large numbers of birds and reptiles can occur in the diet in several areas, and can even be the primary foods. Meanwhile, amphibians, fish and invertebrates can seem rare in the hawk's regular diet, but they are not infrequently taken by immature hawks. Red-tailed hawks may survive on islands absent of native mammals on diets variously including invertebrates such as crabs, as well as lizards or birds. Like many Buteo species, they hunt from a perch most often, but can vary their hunting techniques where prey and habitat demand it.[5][9] Because they are so common and easily trained as capable hunters, in the United States they are the most commonly captured hawks for falconry. Falconers are permitted to take only passage hawks (which have left the nest, are on their own, but are less than a year old) so as to not affect the breeding population. Passage red-tailed hawks are also preferred by falconers because they have not yet developed the adult behaviors that would make them more difficult to train.[10]

Taxonomy

The red-tailed hawk was

The red-tailed hawk is a member of the subfamily

At one time, the rufous-tailed hawk (B. ventralis), distributed in Patagonia and some other areas of southern South America, was considered part of the red-tailed hawk species. With a massive distributional gap consisting of most of South America, the rufous-tailed hawk is considered a separate species now, but the two hawks still compromise a "species pair" or superspecies, as they are clearly closely related. The rufous-tailed hawk, while comparatively little studied, is very similar to the red-tailed hawk, being about the same size and possessing the same wing structure, and having more or less parallel nesting and hunting habits. Physically, however, rufous-tailed hawk adults do not attain a bright brick-red tail as do red-tailed hawks, instead retaining a dark brownish-cinnamon tail with many blackish crossbars similar to juvenile red-tailed hawks.[2][23][24] Another, more well-known, close relative to the red-tailed hawk is the common buzzard (B. buteo), which has been considered as its Eurasian "broad ecological counterpart" and may also be within a species complex with red-tailed hawks. The common buzzard, in turn, is also part of a species complex with other Old World buzzards, namely the mountain buzzard (B. oreophilus), the forest buzzard (B. trizonatus ), and the Madagascar buzzard (B. brachypterus).[2][22][25] All six species, although varying notably in size and plumage characteristics, in the alleged species complex that contains the red-tailed hawk share with it the feature of the blackish patagium marking, which is missing in most other Buteo spp.[2][26]

Subspecies

At least 14 recognized subspecies of B. jamaicensis are described, which vary in range and in coloration. Not all authors accept every subspecies, though, particularly some of the insular races of the tropics (which differ only slightly in some cases from the nearest mainland forms) and particularly Krider's hawk, by far the most controversial red-tailed hawk race, as few authors agree on its suitability as a full-fledged subspecies.[5][9][27]

| Image | Subspecies | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

|

Jamaican red-tailed hawk (B. j. jamaicensis) | occurs throughout the West Indies (including Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles) except for the Bahamas and Cuba. |

|

Alaska red-tailed hawk (B. j. alascensis) | breeds (probably resident) from southeastern coastal Alaska to Haida Gwaii and Vancouver Island in British Columbia. |

|

Eastern red-tailed hawk (B. j. borealis) | breeds from southeast Canada and northern Florida .

|

|

Western red-tailed hawk (B. j. calurus) | greatest longitudinal breeding distribution of any race of red-tailed hawk. |

|

Central American red-tailed hawk (B. j. costaricensis) | from Nicaragua to Panama. |

|

Southwestern red-tailed hawk (B. j. fuertesi) | breeds from northern Chihuahua to South Texas. |

| Tres Marias red-tailed hawk (B. j. fumosus) | endemic to Islas Marías, Mexico. | |

| Mexican Highlands red-tailed hawk (B. j. hadropus) | native to the Mexican Highlands. | |

|

Harlan's hawk (B. j. harlani) | breeds from central Alaska to northwestern Canada, with the largest number of birds breeding in the Yukon or western Alaska, reaching their southern limit in north-central British Columbia. |

| Red-tailed hawk (kemsiesi) (B. j. kemsiesi) | a dark subspecies resident from Chiapas, Mexico, to Nicaragua. | |

|

Krider's hawk (B. j. kriderii) | breeds from southern Alberta, southern Saskatchewan, southern Manitoba, and extreme western Ontario south to south-central Montana, Wyoming, western Nebraska, and western Minnesota. |

| Socorro red-tailed hawk (B. j. socorroensis) | endemic to Socorro Island, Mexico. | |

| Cuban red-tailed hawk (B. j. solitudinis) | native to the Bahamas and Cuba. | |

|

Florida red-tailed hawk (B. j. umbrinus) | occurs year-round in peninsular Florida north to as far Tampa Bay and the Kissimmee Prairie south throughout the rest of peninsular Florida south to the Florida Keys. |

Description

Red-tailed hawk

Though the markings and color vary across the subspecies, the basic appearance of the red-tailed hawk is relatively consistent.

Overall, this species is blocky and broad in shape, often appearing (and being) heavier than other Buteos of similar length. They are the heaviest Buteos on average in eastern North America, albeit scarcely ahead of the larger winged rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus), and second only in size in the west to the ferruginous hawk (Buteo regalis). Red-tailed hawks may be anywhere from the fifth to the ninth heaviest Buteo in the world depending on what figures are used. However, in the northwestern United States, ferruginous hawk females are 35% heavier than female red-tails from the same area.[2] On average, western red-tailed hawks are relatively longer winged and lankier proportioned but are slightly less stocky, compact and heavy than eastern red-tailed hawks in North America. Eastern hawks may also have mildly larger talons and bills than western ones. Based on comparisons of morphology and function amongst all accipitrids, these features imply that western red-tails may need to vary their hunting more frequently to on the wing as the habitat diversifies to more open situations and presumably would hunt more variable and faster prey, whereas the birds of the east, which was historically well-wooded, are more dedicated perch hunters and can take somewhat larger prey but are likely more dedicated mammal hunters.[9][32][33] In terms of size variation, red-tailed hawks run almost contrary to Bergmann's rule (i.e. that northern animals should be larger in relation than those closer to the Equator within a species) as one of the northernmost subspecies, B. j. alascensis, is the second smallest race based on linear dimensions and that two of the most southerly occurring races in the United States, B. j. fuertesi and B. j. umbrinus, respectively, are the largest proportioned of all red-tailed hawks.[9][33][34] Red-tailed hawks tend have a relatively short but broad tails and thick, chunky wings.[30] Although often described as long-winged,[2][4] the proportional size of the wings is quite small and red-tails have high wing loading for a buteonine hawk. For comparison, two other widespread Buteo hawks in North America were found to weigh: 30 g (1.1 oz) for every square centimeter of wing area in the rough-legged buzzard (B. lagopus) and 44 g (1.6 oz)/cm2 in the red-shouldered hawk (B. lineatus). In contrast, the red-tailed hawk weighed considerably more for their wing area: 199 g (7.0 oz) per square cm.[35]

As is the case with many raptors, the red-tailed hawk displays sexual dimorphism in size, as females are on average 25% larger than males.

Male red-tailed hawks can measure 45 to 60 cm (18 to 24 in) in total length, females measuring 48 to 65 cm (19 to 26 in) long. Their wingspan typically can range from 105 to 141 cm (3 ft 5 in to 4 ft 8 in), although the largest females may possible span up to 147 cm (4 ft 10 in). In the standard scientific method of measuring wing size, the

Identification

Although they overlap in range with most other American diurnal raptors, identifying most mature red-tailed hawks to species is relatively straightforward, particularly if viewing a typical adult at a reasonable distance. The red-tailed hawk is the only North American hawk with a rufous tail and a blackish

Vocalization

The cry of the red-tailed hawk is a 2- to 3-second, hoarse, rasping scream, variously transcribed as kree-eee-ar, tsee-eeee-arrr or sheeeeee,[49] that begins at a high pitch and slurs downward.[2][27][50] This cry is often described as sounding similar to a steam whistle.[31][27] The red-tailed hawk frequently vocalizes while hunting or soaring, but vocalizes loudest and most persistently in defiance or anger, in response to a predator or a rival hawk's intrusion into its territory.[27][49] At close range, it makes a croaking guh-runk, possibly as a warning sound.[51] Nestlings may give peeping notes with a "soft, sleepy quality" that give way to occasional screams as they develop, but those are more likely to be a soft whistle rather than the harsh screams of the adults. Their latter hunger call, given from 11 days (as recorded in Alaska) to after fledgling (in California), is different, a two-syllabled, wailing klee-uk food cry exerted by the young when parents leave the nest or enter their field of vision.[5][52] A strange mechanical sound "not very unlike the rush of distant water" has been reported as uttered in the midst of a sky-dance.[5] A modified call of chirp-chwirk is given during courtship, while a low key, duck-like nasal gank may be given by pairs when they are relaxed.[27]

The fierce, screaming cry of the adult red-tailed hawk is frequently used as a generic raptor sound effect in television shows and other media, even if the bird featured is not a red-tailed hawk.[53][54] It is especially used in depictions of the bald eagle, which contributes to the common misconception that it is a bald eagle cry; actual bald eagle vocalizations are far softer and more chirpy than those of a red-tailed hawk.[55]

Distribution and habitat

The red-tailed hawk is one of the most widely distributed of all raptors in the Americas. It occupies the largest breeding range of any diurnal raptor north of the Mexican border, just ahead of the

Red-tailed hawks have shown the ability to become habituated to almost any habitat present in North and Central America. Their preferred habitat is mixed forest and

In the northern Great Plains, the widespread practices of wildfire suppression and planting of exotic trees by humans has allowed groves of aspen and various other trees to invade what was once vast, almost continuous prairie grasslands, causing grassland obligates such as ferruginous hawks to decline and allowing parkland-favoring red-tails to flourish.[5][64] To the contrary, clear-cutting of mature woodlands in New England, resulting in only fragmented and isolated stands of trees or low second growth remaining, was recorded to also benefit red-tailed hawks, despite being to the determent of breeding red-shouldered hawks.[65] The red-tailed hawk, as a whole, rivals the peregrine falcon and the great horned owl among raptorial birds in the use of diverse habitats in North America.[5][66] Beyond the high Arctic (as they discontinue as a breeder at the tree line), few other areas exist where red-tailed hawks are absent or rare in North and Central America. Some areas of unbroken forest, especially lowland tropical forests, rarely host red-tailed hawks, although they can occupy forested tropical highlands surprisingly well. In deserts, they can only occur where some variety of arborescent growth or ample rocky bluffs or canyons occur.[28][67][68]

Behavior

The red-tailed hawk is highly conspicuous to humans in much of its daily behavior. Most birds in resident populations, which are well more than half of all red-tailed hawks, usually split nonbreeding-season activity between territorial soaring flight and sitting on a perch. Often, perching is for hunting purposes, but many sit on a tree branch for hours, occasionally stretching on a single wing or leg to keep limber, with no signs of hunting intent.

Flight

In flight, this hawk soars with wings often in a slight dihedral, flapping as little as possible to conserve energy. Soaring is by far the most efficient method of flight for red-tailed hawks, so is used more often than not.[74] Active flight is slow and deliberate, with deep wing beats. Wing beats are somewhat less rapid in active flight than in most other Buteo hawks, even heavier species such as ferruginous hawks tend to flap more swiftly, due to the morphology of the wings.[75] In wind, it occasionally hovers on beating wings and remains stationary above the ground, but this flight method is rarely employed by this species.[9][28] When soaring or flapping its wings, it typically travels from 32 to 64 km/h (20 to 40 mph), but when diving may exceed 190 km/h (120 mph).[50] Although North American red-tailed hawks will occasionally hunt from flight, a great majority of flight by red-tails in this area is for non-hunting purpose.[74] During nest defense, red-tailed hawks may be capable of surprisingly swift, vigorous flight, while repeatedly diving at perceived threats.[76]

Migration

Red-tailed hawks are considered partial migrants, as in about the northern third of their distribution, which is most of their range in Canada and Alaska, they almost entirely vacate their breeding grounds.

Immature hawks migrate later than adults in spring on average, but not, generally speaking, in autumn. In the northern Great Lakes, immatures return in late May to early June, when adults are already well into their nesting season and must find unoccupied ranges.

Diet

The red-tailed hawk is

The talons and feet of red-tailed hawks are relatively large for a Buteo hawk; in an average-sized adult red-tail, the "hallux-claw" or rear talon, the largest claw on all accipitrids, averages about 29.7 mm (1.17 in).[32][90] In fact, the talons of red-tails in some areas averaged of similar size to those of ferruginous hawks which can be considerably heavier and notably larger than those of the only slightly lighter Swainson's hawk.[32][91][92] This species may exert an average of about 91 kg/cm2 (1,290 lbf/in2) of pressure through its feet.[32][93][94] Owing to its morphology, red-tailed hawks generally can attack larger prey than other Buteo hawks typically can, and are capable of selecting the largest prey of up to their own size available at the time of hunting, though in all likelihood numerically most prey probably weighs on average about 20% of the hawk's own weight (as is typical of many birds of prey).[9][39][95] Red-tailed hawks usually hunt by watching for prey activity from a high perch, also known as still hunting. Upon being spotted, prey is dropped down upon by the hawk. Red-tails often select the highest available perches within a given environment, since the greater the height they are at, the less flapping is required and the faster the downward glide they can attain toward nearby prey. If prey is closer than average, the hawk may glide at a steep downward angle with few flaps, if farther than average, it may flap a few swift wingbeats alternating with glides. Perch hunting is the most successful hunting method generally speaking for red-tailed hawks and can account for up to 83% of their daily activities (i.e. in winter).[9][5][96] Wintering pairs may join and aseasonally may join forces to group hunt agile prey that they may have trouble catching by themselves, such as tree squirrels. This may consist of stalking opposites sides of a tree, to surround the squirrel and almost inevitably drive the rodent to be captured by one after being flushed by the other hawk.[5][27]

The most common flighted hunting method for red-tail is to cruise around 10 to 50 m (33 to 164 ft) over the ground with flap-and-glide type flight, interspersed occasionally with

Mammals

Rodents are certainly the type of prey taken most often by frequency, but their contribution to prey biomass at nests can be regionally low, and the type, variety, and importance of rodent prey can be highly variable. In total, well over 100 rodent species have turned up the diet of red-tailed hawks.

By far, the most important prey among rodents is

In Kluane Lake, Yukon, 750 g (1.65 lb) Arctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus parryii) were the main overall food for Harlan's red-tailed hawks, making up 30.8% of a sample of 1074 prey items. When these ground squirrels enter their long hibernation, the breeding Harlan's hawks migrate south for the winter.[128] Nearly as important in Kluane Lake was the 200 g (7.1 oz) American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), which constituted 29.8% of the above sample. Red squirrels are highly agile dwellers on dense spruce stands, which has caused biologists to ponder how the red-tailed hawks are able to routinely catch them. It is possible that the hawks catch them on the ground such as when squirrels are digging their caches, but theoretically, the dark color of the Harlan's hawks may allow them to ambush the squirrels within the forests locally more effectively.[5][127][128] While American red squirrels turn up not infrequently as supplementary prey elsewhere in North America, other tree squirrels seem to be comparatively infrequently caught, at least during the summer breeding season. It is known that pairs of red-tailed hawks will cooperatively hunt tree squirrels at times, probably mostly between late fall and early spring. Fox squirrels (Sciurus niger), the largest of North America's tree squirrels at 800 g (1.8 lb), are relatively common supplemental prey but the lighter, presumably more agile 533 g (1.175 lb) eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) appears to be seldom caught based on dietary studies.[9][84][126][127][129] While adult marmot may be difficult for red-tailed hawks to catch, young marmots are readily taken in numbers after weaning, such as a high frequency of yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) in Boulder, Colorado.[130] Another grouping of squirrels but at the opposite end of the size spectrum for squirrels, the chipmunks are also mostly supplemental prey but are considered more easily caught than tree squirrels, considering that they are more habitual terrestrial foragers.[5][4][85] In central Ohio, eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus), the largest species of chipmunk at an average weight of 96 g (3.4 oz), were actually the leading prey by number, making up 12.3% of a sample of 179 items.[129][131]

Outside of rodents, the most important prey for North American red-tailed hawks is

In the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska, red-tails are fairly dependent on the snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), falling somewhere behind the great horned owl and ahead of the American goshawk in their regional reliance on this food source.[77][128][125] The hunting preferences of red-tails who rely on snowshoe hares are variable. In Rochester, Alberta, 52% of snowshoe hares caught were adults, such prey estimated to average 1,287 g (2.837 lb), and adults, in some years, were six times more often taken than juvenile hares, which averaged an estimated 560 g (1.23 lb). 1.9–7.1% of adults in the regional population of Rochester were taken by red-tails, while only 0.3–0.8 of juvenile hares were taken by them. Despite their reliance on it, only 4% (against 53.4% of the biomass) of the food by frequency here was made up of hares.[125] On the other hand, in Kluane Lake, Yukon, juvenile hares were taken roughly 11 times more often than adults, despite the larger size of adults here, averaging 1,406.6 g (3.101 lb), and that the overall prey base was less diverse at this more northerly clime. In both Rochester and Kluane Lake, the number of snowshoe hares taken was considerably lower than the number of ground squirrels taken. The differences in average characteristics of snowshoe hares that were hunted may be partially due to habitat (extent of bog openings to dense forest) or topography.[128][139] Another member of the Lagomorpha order has been found in the diet include juvenile white-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii) and the much smaller American pika (Ochotona princeps), at 150 g (5.3 oz).[91][140][141]

A diversity of mammals may be consumed opportunistically outside of the main food groups of rodents and leporids, but usually occur in low numbers. At least five species each are taken of

Birds

Like most (but not all)

Beyond galliforms, three other quite different families of birds make the most significant contributions to the red-tailed hawk's avian diet. None of these three families are known as particularly skilled or swift fliers, but are generally small enough that they would generally easily be more nimble in flight. One of these are the

Over 50 passerine species from various other families beyond corvids, icterids and starlings are included in the red-tailed hawks' prey spectrum but are caught so infrequently as to generally not warrant individual mention.

How large of a duck that red-tailed hawks can capture may be variable. In one instance, a red-tailed hawk failed to kill a healthy drake

Reptiles

Early reports claimed relatively little predation of reptiles by red-tailed hawks but these were regionally biased towards the east coast and the upper Midwest of the United States.[187] However, locally the predation on reptiles can be regionally quite heavy and they may become the primary prey where large, stable numbers of rodents and leporids are not to be found reliably. Nearly 80 species of reptilian prey have been recorded in the diet at this point.[5][85][86] Most predation is on snakes, with more than 40 species known in the prey spectrum. The most often found reptilian species in the diet (and sixth overall in 27 North American dietary studies) was the gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer). Red-tails are efficient predators of these large snakes, which average about 532 to 747 g (1.173 to 1.647 lb) in adults, although they also take many small and young gopher snakes.[89][122][188][189][190][191] Along the Columbia River in Washington, large colubrid snakes were found to be the primary prey, with the eastern racer (Coluber constrictor), which averages about 556 g (1.226 lb) in mature adults, the most often recorded at 21.3% of 150 prey items, followed by the gopher snake at 18%. This riverine region lacks ground squirrels and has low numbers of leporids. 43.2% of the overall diet here was made up of reptiles, while mammals, made up 40.6%.[188][192] In the Snake River NCA, the gopher snake was the second most regularly recorded (16.2% of 382 items) prey species over the course of the years and did not appear to be subject to the extreme population fluctuations of mammalian prey here.[89] Good numbers of smaller colubrids can be taken as well, especially garter snakes.[85][91][106] Red-tailed hawks may engage in avoidance behavior to some extent with regard to venomous snakes. For example, on the San Joaquin Experimental Range in California, they were recorded taking 225 gopher snakes against 83 western rattlesnakes (Crotalus oreganus). Based on surveys, however, the rattlesnakes were five times more abundant on the range than the gopher snakes.[5][119] Nonetheless, the red-tailed hawk's diet has recorded at least 15 venomous snakes.[85][86] Several predation on adult rattlesnakes have reported, including adult eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) about 126.4 cm (4 ft 2 in) in snout-to-vent length.[193] These rattlesnakes are the heaviest venomous snakes in America, with a mature size of about 2,300 g (5.1 lb), and can be hazardous to hawks, though an immature red-tail was photographed killing a "fairly large" eastern diamondback rattlesnake in one instance.[16][194][195] Additionally, eastern indigo snakes (Drymarchon couperi), North America's longest native snake can be taken as well.[196] While these large snakes are usually dispatched on the ground, red-tailed hawks have been seen flying off with snake prey that may exceed 153 cm (5 ft 0 in) in length in some cases.[9] At the opposite end of the scale in snake prey, the smallest known snake known to be hunted by red-tailed hawks is the 6 g (0.21 oz) redbelly snake (Storeria occipitomaculata).[197]

In North America, fewer lizards are typically recorded in the foods of red-tailed hawks than are snakes, probably because snakes are considerably better adapted to cooler, seasonal weather, with an extensive diversity of lizards found only in the southernmost reaches of the

Other prey

Records of predation on

Interspecies predatory relationships

As easily one of the most abundant of all American raptorial birds, red-tailed hawks have been recorded as interacting with every other diurnal bird of prey. Due to the extreme dietary plasticity of red-tails, the food habits of other birds of prey regularly overlap considerably with red-tails. Furthermore, due to its ability to nest in varied habitats, home ranges also frequently abut those of other raptor species.[5][9] The most obvious similar species in their range are other Buteo hawks, especially larger species with a similar ecological niche. Two of the larger, more widespread other Buteos are the Swainson's hawk and the ferruginous hawks and, as with many other birds of prey, red-tailed hawks occur in almost the entirety of these birds' breeding ranges.[9][211] These species have broadly similar breeding season diets, especially the ferruginous and red-tailed hawks. In some areas, such as Snake River NCA the diets of the two species consist of more than 90% of the same species and body mass of prey taken was similar.[89][91] Therefore, all three large Buteo hawks defend their territories from each other with almost the same degree of dedication that they defend from others of their own species. In some cases, territorial clashes of Swainson's hawks and red-tailed hawks can last up to 12 hours, however, the birds involved are usually careful to avoid physical contact.[5][212] Due to the similarities of the foods and their aggressive dispositions towards one another, these Buteos need some degree of partitioning in order to persist alongside one another and this usually is given by habitat preferences. The ferruginous hawk prefers open, practically treeless prairie while of these, the red-tailed hawks prefers the most wooded areas with large trees, while the Swainson's hawk prefer roughly intermediate areas.[91][212][8] Where the habitat is more open, such as in Cassia County, Idaho, the Swainson's and ferruginous hawks have the advantage in numbers and red-tails are scarce.[213] However, habitat alterations by humans, such as fire suppression and recovering pasture, usually favor the red-tailed hawk and are to the detriment of the other two species.[211][214][64] These practices have caused range expansions of many other species of birds but declines in many others.[215][216][217] Of these three Buteo species, the Swainson's hawk is most dissimilar, being a long-distance migrant which travels to South America each winter and, for much of the year, prefers to prey on insects (except for during breeding, when more nutritious food such as ground squirrels are mainly fed to the young). It also breeds notably later than the other two species.[218] Surprisingly, although it's slightly smaller in body mass and has notably smaller (and presumably weaker) feet than ferruginous and red-tailed hawks, the Swainson's is actually usually (but not invariably) dominant in territorial conflicts over the other two. Part of this advantage is that the Swainson's hawk is apparently a superior flier both in long and short-distance flights, with its more pointed wing shape and lower wing loading allowing it more agile, sustained and speedier flight that the bulkier hawks cannot match.[219] Therefore, in north-central Oregon, Swainson's hawks were shown to be more productive, in prairie located trees, and partially displaced prior-breeding red-tails several times, although overall breeding success rates were not perceptibly decreased in the latter hawk.[212][220] In the Chihuahuan Desert of Mexico, Swainson's hawks usually nested in lowlands and red-tails nested in highlands but interspecies conflicts nevertheless were apparently quite frequent. Usually, the habitat preferences of red-tailed hawks and ferruginous hawks are discrepant enough to keep serious territorial conflicts to a minimum.[89][212] However, red-tailed hawks and ferruginous hawks occasionally engaged in kleptoparasitism towards one another, usually during winter. Red-tails may be somewhat dominant based on prior reports in food conflicts but the ferruginous hawk may also win these.[4] Where they overlap, the hawk species may adjust their daily routine to minimize contact, which tends to be costly of time and energy and may cause the hawks to abandon their nests for long stretches of time, which in turn leaves their young vulnerable to predation.[5] When habitats change rapidly, often due to human interference, and they nest more closely than natural partitioning would allow, in all three nesting success can decline significantly.[8]

Beyond the Swainson's and ferruginous hawks, six other Buteos co-occur with red-tailed hawks in different parts of North America. Many of these are substantially smaller than red-tails and most serious territorial conflicts with them are naturally mitigated by nesting in deeper wooded areas.

Hawks and kites from outside the buteonine lineage are usually substantially smaller or at least different enough in diet and habitat to largely avoid heavy conflict with red-tailed hawks. On occasion, northern harriers (Circus hudsonius) which have much lower wing loading, will mob red-tailed hawks out of their home ranges but in winter the red-tails seem to be dominant over them in conflicts over food.[155][225] Among Accipiter hawks, the most similar to the red-tailed hawk in diet and size is the American goshawk. In some areas, the prey species of these can be very similar and North American populations of goshawks take many more squirrels and leporids than their Eurasian counterparts do.[128][226] It was found that the feet and striking force of hunting goshawks was more powerful than that of the red-tailed hawk, despite the red-tails being up to 10% heavier in some parts of North America.[94] Therefore, wild goshawks can dispatch larger prey both on average and at maximum prey size, with some victims of female goshawks such as adult hares and galliforms such as turkey and capercaillie weighing up to or exceeding roughly 4,000 g (8.8 lb).[227][228][229] In a comparative study in the Kaibab Plateau of Arizona, however, it was found that red-tailed hawks had several population advantages. Red-tails were more flexible in diet, although there was a very broad overlap in prey species selected, and nesting habitat than the goshawks were.[136] As red-tailed hawks in conflict with other more closely related Buteo hawks rarely (if ever) result in mortality on either side, goshawks and red-tailed hawks do seem to readily kill one another. Adults of both species have been shown to be able to kill adults of the other.[125][230][231][232][excessive citations]

The great horned owl occupies a similar ecological niche nocturnally to the red-tailed hawk.[88] There have been many studies that have contrasted the ecology of these two powerful raptors.[39][84][129] The great horned owl averages heavier and larger footed, with northern populations averaging up to 26% heavier in the owl than the hawk.[39] However, due in part to the red-tail's more extensive access to sizable prey such as ground squirrels, several contrasting dietary studies found that the estimated mean prey size of the red-tailed hawk, at 175 g (6.2 oz), was considerably higher than that of the great horned owl, at 76 g (2.7 oz).[88] Also, the diet of red-tailed hawk seems to be more flexible by prey type, as only just over 65% of their diet is made of mammals, whereas great horned owls were more restricted feeders on mammals, selecting them 87.6% of the time.[85][86][233] However, the overall prey spectrum of great horned owls includes more species of mammals and birds (but far less reptiles) and the great horned owl can attack prey of a wider size range, including much larger prey items than any taken by red-tailed hawks. Mean prey weights in different areas for great horned owls can vary from 22.5 to 610.4 g (0.79 to 21.53 oz), so is far more variable than that of red-tailed hawks (at 43.4 to 361.4 g (1.53 to 12.75 oz)) and can be much larger (by about 45%) than the largest estimated size known for the red-tailed hawk's mean prey weight but conversely the owl can also subsist on prey communities averaging much smaller in body size than can support the hawk.[234][235] Some prey killed by great horned owls was estimated to weigh up to 6,800 g (15.0 lb).[85][233][236] Great horned owls and red-tailed hawks compete not only for food but more seriously over nesting areas and home ranges. Great horned owls are incapable of constructing nests and readily expropriate existing red-tail nests. The habitat preferences of the two species are quite similar and the owl frequently uses old red-tail nests, but they do seem to prefer more enclosed nest locations where available over the generally open situation around red-tailed hawk nests. Sometimes in warmer areas, the owls may nest sufficiently early to have fledged young by the time red-tails start to lay. However, when there is a temporal overlap in reproductive cycles, the owl sometimes takes over an occupied red-tail nest, causing desertion. Red-tailed hawks have an advantage in staple prey flexibility as aforementioned, while great horned owl populations can be stressed when preferred prey is scarce, especially when they rely on leporids such as hares and jackrabbits.[5][88][128][112][excessive citations] For example, in Alberta, when snowshoe hares were at their population peak, red-tailed hawks did not increase in population despite taking many, with only a slight increase in mean clutch size, whereas the owls fluctuated in much more dramatic ways in accordance with snowshoe hare numbers. The red-tails migratory behavior was considered as the likely cause of this lack of effect, whereas great horned owls remained through the winter and was subject to winter-stress and greater risk of starvation.[237] As a nester, great horned owl has the advantage in terms of flexibility, being somewhat spread more evenly across different habitats whereas in undisturbed areas, red-tailed hawks seem to nest more so in clusters where habitat is favorable.[5][84][129][237][excessive citations] Predatory relationships between red-tailed hawks and great horned owls are quite one-sided, with the great horned owl likely the overall major predator of red-tails. On the other hand, red-tailed hawks are rarely (if ever) a threat to the great horned owl. Occasionally a red-tailed hawk can strike down an owl during the day but only in a few singular cases has this killed an owl.[238][239] Most predation by the owls on the hawks is directed at nestlings at the point where the red-tails' nestlings are old enough that the parents no longer roost around the nest at night. Up to at least 36% of red-tailed hawk nestlings in a population may be lost to great horned owls.[5][125] Adult and immature red-tailed hawks are also occasionally preyed upon at night by great horned owls in any season. In one case, a great horned owl seemed to have ambushed, killed and fed upon a full-grown migrating red-tail even in broad daylight.[5][65] Occasionally, both red-tails and great horned owls will engage each other during the day and, even though the red-tailed hawk has the advantage at this time of day, either may succeed in driving away the other.[4][65][237] Despite their contentious relations, the two species may nest quite close to one another. For example, in Saskatchewan, the smallest distance between nests was only 32 to 65 m (105 ft 0 in to 213 ft 3 in). In these close proximity areas all owl nests succeeded while only two red-tail nests were successful.[240] In Waterloo, Wisconsin, the two species were largely segregated by nesting times, as returning red-tailed hawks in April–June were usually able to successfully avoid nesting in groves holding great horned owls, which can begin nesting activities as early as February.[241] In Delaware County, Ohio and in central New York state, divergence of hunting and nesting times usually allowed both species to succeed in nesting. In all three areas, any time the red-tails tried to nest closer to great horned owls, their breeding success rates lowered considerably. It is presumable that sparser habitat and prey resources increased the closeness of nesting habits of the two species, to the detriment of the red-tails. Due to nesting proximity to great horned owls, mature red-tails may have losses ranging from 10 to 26%.[125][129][240][242][excessive citations]

Red-tailed hawks may face competition from a very broad range of predatory animals, including birds outside of typically active predatory families, carnivoran mammals and some reptiles such as snakes. Mostly these diverse kinds of predators are segregated by their hunting methods, primary times of activity and habitat preferences. In California, both the red-tails and western diamondback rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox) live mainly on California ground squirrel, but the rattlesnake generally attacks the squirrels in and around their burrows, whereas the hawks must wait until they leave the burrows to capture them.[243] Hawks have been observed following American badgers (Taxidea taxus) to capture prey they flush and the two are considered potential competitors, especially in sparse sub-desert areas where the rodent foods they both favor are scarce.[244] Competition over carcasses may occur with American crows, and several crows, usually about six or more, working together can displace a hawk.[245] Another avian scavenger, the turkey vulture (Cathartes aura), is dominated by red-tails and may be followed by red-tails in order to supplant a carcass found by the vulture with their keen sense of smell.[246] In some cases, red-tailed hawks may be considered lessened as food competitors by their lack of specialization. For instance, no serious competition probably occurs between them and Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) despite both living on snowshoe hares.[247]

Distinguishing territorial exclusionary behavior and anti-predator behavior is difficult in raptorial birds. However, as opposed to other medium to largish hawks which chase off red-tails most likely as competition, in much smaller raptors such as

In turn, red-tailed hawks may engage in behavior that straddles territorial exclusion and anti-predator behavior to the two much larger raptors in North America which actively hunt, the

Reproduction

Courtship and pre-laying behaviors

Pairs either court for the first time or engage in courtship rituals to strengthen pre-existing pair bonds before going into the breeding. The breeding season usually begins in late February through March, but can commence as early as late December in Arizona and late January in Wisconsin or to the opposite extreme as late as mid-April as in Alberta.[9][84][125][223][excessive citations] In this pre-nesting period, high-circling with much calling will occur. One or both members of a pair may be involved. The courtship display often involves dangling legs, at times the pair will touching each other's wings and male's feet may touch female's back, she may occasionally roll over and present talons. Food passes are rarely reported.[2][9][77] High soaring occurs aseasonally. Circling above territory tends to be done noisily and conspicuously, helping insure against possible takeovers. Spring circling of a pair can be a prelude to copulation.[27] A typical sky-dance involves the male hawk climbing high in flight with deep, exaggerated beats and then diving precipitously on half-closed wings at great speed, checking, and shooting back up, or often plunging less steeply and repeating process in a full rollercoaster across the sky. Sky-dances are done on periphery of the pair's territory and it appears to designate the territory limits, occasionally one male's sky-dance may also trigger a sky-dance by a neighboring male, who may even run a parallel course in the sky. Sky-dances no longer occur after late incubation.[2][5][65] Boundary flight displays may be engaged in by all four birds of 2 adjacent pairs.[27] Cartwheeling with interlocking talons is also seen occasionally in spring, almost always a territorial male expelling an intruding one, the latter often being a second or third year male that is newly mature. A perched display, with fluffed-out breast feathers may too occur at this time. Even males that are in spring migration have been recorded engaging in a separate display: circling at slow speed before partially closing wings, dropping legs with talons spread and tilting from side-to-side. A female hawk is usually around when migrating male does this but she does not engage in this display herself.[2][5] The area of occupancy of breeding territories by pairs is variable based on regional habitat composition. The highest recorded density of pairs was in California where each pair occurred on 1.3 km2 (0.50 sq mi), which was actually just ahead of Puerto Rico where pair occupancy averaged 1.56 km2 (0.60 sq mi) in peak habitat. The largest known average territory sizes were surprisingly in Ohio, where the average area of occupancy by pairs was recorded as 50 km2 (19 sq mi).[9][100][119] In Wisconsin mean ranges for males range from 1.17 to 3.9 km2 (0.45 to 1.51 sq mi) in males and from 0.85 to 1.67 km2 (0.33 to 0.64 sq mi) in females, respectively in summer and winter. Here and elsewhere, both members of the pair stay quite close together throughout winter if they are sedentary. On the other hand, migrant populations tend to separate while migrating and return to the same territory to find its prior mate, sometimes before they reach their home range.[9][100][241] In Alaska, returning migrant pairs were able to displace lone red-tailed hawks that had stayed on residence, especially lone males but sometimes even lone females.[77] In general, the red-tailed hawk will only take a new mate when its original mate dies.[271] Although pairs often mate for life, replacement of mates can often be quite fast for this common bird species. In one case in Baja California, when a female was shot on 16 May, the male of that pair was seen to have selected a new mate the following day.[5][272] In copulation, the female, when perched, tilts forward, allowing the male to land with his feet lodged on her horizontal back. The female twists and moves her tail feathers to one side, while the mounted male twists his cloacal opening around the female's cloaca. Copulation lasts 5 to 10 seconds and during pre-nesting courtship in late winter or early spring can occur numerous times each day.[273]

Nests

The pair constructs a stick

Eggs

In most of the interior

Hatching, development and brooding

After 28 to 35 days of incubation (averaging about three days longer in the Caribbean as does fledgling as compared to North American red-tails), the eggs hatch over 2 to 4 days.

Fledging and immaturity

Young typically leave the nest for the first time and attempt their first flights at about 42–46 days after hatching but usually they stay very near the nest for the first few days. During this period, the fledglings remain fairly sedentary, though they may chase parents and beg for food. Parents deliver food directly or, more commonly, drop it near the young. Short flights are typically undertaken for the first 3 weeks after fledgling and the young red-tails activity level often doubles. About 6 to 7 weeks after fledging, the young begin to capture their own prey, which often consists of insects and frogs that the young hawks can drop down to onto the ground with relative ease. At the point they are 15 weeks old, they may start attempts to hunt more difficult mammal and bird prey in sync with their newly developed skills for sustained flight, and most are efficient mammal predators fairly soon after their first attempts at such prey. Shortly thereafter, when the young are around 4 months of age, they become independent of their parents. In some extreme cases, juvenile red-tails may prolong their association with their parents to as long as they are half a year old, as was recorded in Wisconsin.[241][4][296][297][excessive citations] After dispersing from the parental territory, juveniles from several nests may congregate and interact in a juvenile staging area. Although post-fledgling siblings in their parents care are fairly social, they are rarely seen together post distribution from their parents range.[9][298] Usually, newly independent young hawks leave the breeding area and migrate, if necessary, earlier than adults do, however the opposite was true in the extreme north of Alaska, where adults were recorded to leave first.[298][299] Immature hawks in migratory populations tend to distribute further in winter than adults from these populations do.[300] Immatures attempting to settle for the winter often are harassed from territory to territory by older red-tails, settling only in small, marginal areas. In some cases, such as near urban regions, immatures may be driven to a small pockets of urban vegetation with less tree cover and limited food resources. When a distant adult appears, immatures may drop from a prominent perch to a more concealed one.[27][84] In some cases, hungry immature red-tails have been recorded making attempts at hunting prey beyond their capacities, expending valuable energy, such as healthy adults of larger carnivorans such as coyotes (Canis latrans), foxes and badgers and healthy flying passerines.[5] There are some cases of red-tailed hawks, presumably younger than two years of age, attempting to breed, often with an adult bird of the opposite sex. Such cases have been recorded in Alberta, Arizona and Wisconsin, with about half of these attempts being successful at producing young.[125][166][287][301][excessive citations] However, while adult plumage and technically sexual maturity is attained at two years old, many red-tails do not first successfully breed until they are around 3 years of age.[9]

Breeding success and longevity

Breeding success is variable due to many factors. Estimated nesting success usually falls between 58% and 93%.

Relationship with humans

Use in falconry

The red-tailed hawk is a popular bird in falconry, particularly in the United States where the sport of falconry is tightly regulated; this type of hawk is widely available and is frequently assigned to apprentice falconers.[308] Red-tailed hawks are highly tameable and trainable, with a more social disposition than all other falcons or hawks other than the Harris's hawk.[309] They are also long lived and fairly disease resistant, allowing a falconer to maintain a red-tailed hawk as a hunting companion for potentially up to two decades.[10] There are fewer than 5,000 falconers in the United States, so despite their popularity any effect on the red-tailed hawk population, estimated to be about one million in the United States, is negligible.[310]

Not being as swift as

In the course of a typical hunt, a falconer using a red-tailed hawk most commonly releases the hawk and allows it to perch in a tree or other high vantage point. The falconer, who may be aided by a dog, then attempts to flush prey by stirring up ground cover. A well-trained red-tailed hawk will follow the falconer and dog, realizing that their activities produce opportunities to catch game. Once a raptor catches game, it does not bring it back to the falconer. Instead, the falconer must locate the bird and its captured prey, "make in" (carefully approach) and trade the bird off its kill in exchange for a piece of offered meat.[10][311]

-

A trained red-tailed hawk working with a volunteer from the Ojai Raptor Center

-

A falconer's red-tailed hawk comes in for a landing

Feathers and Native American use

The

Citations

- ^ . Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7136-8026-3.

- ^ "Red-tailed Hawk". All About Birds. Cornell University. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Preston, C. R. (2000). Red-tailed Hawk. Stackpole Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw Palmer, R. S., ed. (1988). Handbook of North American birds. Volume 5 Diurnal Raptors (part 2).

- ISBN 978-1-62349-006-5.

- ^ "Red-tailed Hawk". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ PMID 7427802.

- ^ doi:10.2173/bna.52.

- ^ a b c Beebe, F. L. (1976). North American Falconry and Hunting Hawks. Hancock House Books (British Columbia).

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1788). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 1 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 266.

- ^ Latham, John (1781). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 1, Part 1. London: Printed for Benj. White. pp. 49–50.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 371.

- ^ Lacépède, Bernard Germain de (1799). "Tableau des sous-classes, divisions, sous-division, ordres et genres des oiseux". Discours d'ouverture et de clôture du cours d'histoire naturelle (in French). Paris: Plassan. p. 4. Page numbering starts at one for each of the three sections.

- ^ Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors". IOC World Bird List Version 10.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-84-87334-15-3.

- ^ Brodkorb, P. (1964). Catalogue of fossil birds: Part 2 (Anseriformes through Galliformes). University of Florida.

- S2CID 85907449.

- PMID 23922908.

- ^ Suarez, William (2004). "The Identity of the Fossil Raptor of the Genus Amplibuteo (Aves: Accipitridae) from the Quaternary of Cuba" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 40 (1): 120–125.

- ^ "Buteo jamaicensis (J. F. Gmelin, 1788)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ PMID 12695095.

- JSTOR 4082848.

- ^ Clark, W. S. (1986). "What is Buteo ventralis?" (PDF). Birds Prey Bull. 3: 115–118.

- S2CID 6270968. Archived from the original(PDF) on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- S2CID 84053997.

- ^ ISBN 978-1555214722.

- ^ a b c "Red-tailed Hawk" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ Clark, W.S. (2014). HARLAN’S HAWK differs from RED-TAILED HAWK Archived 13 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Global Raptor Information Network.

- ^ a b c "Buteo jamaicensis". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d Dewey, T.; Arnold, D. "Buteo jamaicensis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Pearlstine, E. V.; Thompson, D. B. (2004). "Geographic variation in morphology of four species of migratory raptors". Journal of Raptor Research. 38: 334–342.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, B. M.; Dunk, J. R. (1999). "Ecogeographic variation in morphology of Red-tailed Hawks in western North America". Journal of Raptor Research. 33 (4): 305–312.

- S2CID 11954818.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 3676627.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ S2CID 26662247.

- JSTOR 27639302.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Buteos" (PDF). Alaska Department of Fish & Game. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Craighead, J. J. and F. C. Craighead, Jr. (1956). Hawks, owls and wildlife. Stackpole Co. Harrisburg, PA.

- ^ a b Snyder, N. F. R. and Wiley, J. W. (1976). "Sexual size dimorphism in hawks and owls of North America" Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Ornithological Monographs, Vol. 20, pp. i–vi, 1–96.

- S2CID 84140038.

- ^ JSTOR 4761.

- ^ Franson, J. C., Thomas, N. J., Smith, M. R., Robbins, A. H., Newman, S., & McCartin, P. C. (1996). "A retrospective study of postmortem findings in red-tailed hawks". Journal of Raptor Research. 30 (1): 7–14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - JSTOR 4509472.

- ^ Red-tailed Hawk videos, photos and facts Archived 4 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Arkive.org. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- .

- ^ a b Robbins, C. S., Bruun, B., & Zim, H. S. (2001). Birds of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Macmillan.

- ^ Liguori, J. & Sullivan, B.L. (2010). "Comparison of Harlan's hawk with Eastern & Western Red-tailed Hawks". Birding: 30–37.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Red-tailed Hawk" (PDF). Sky-hunters.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ a b Day, Leslie. "The City Naturalist – Red Tailed Hawk". 79th Street Boat Basin Flora and Fauna Society. Archived from the original on 27 June 1997. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- ^ "Red-Tailed Hawk". Oregon Zoo. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ "Red-tailed Hawk – Buteo jamaicensis". The Hawk Conservancy Trust. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ^ "San Diego Zoo's Animal Bytes: Red-Tailed Hawk". San Diego Zoo. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Salon. 28 December 2013. Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2013.

- ^ Jessica Robinson, "Bald Eagle: A Mighty Symbol, With A Not-So-Mighty Voice"; NPR, July 2, 2012; accessed 2019.08.23.

- ^ a b American Ornithologists' Union. 1998a. Check-list of North American birds. 7th edition ed. Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

- ^ Tesky, Julie L. "Buteo jamaicensis". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ^ Bildstein, K. L., & Therrien, J. F. (2018). Urban birds of prey: a lengthy history of human-raptor cohabitation. In Urban Raptors (pp. 3–17). Island Press, Washington, DC.

- ^ Pale Male – Introduction – Red-tailed Hawk in New York City | Nature. PBS (May 2004). Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- ^ Geist, Bill (10 July 2003). "In Love With a Hawk". CBS.

- ^ Pale Male – the Central Park Red Tail Hawk Archived 29 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine website

- ^ a b c Winn, M. 1999. Red-tails in love. A Wildlife Drama in Central Park. New York, NY: Vintage Departures, Vintage Books, Random Haouse, Inc.

- ^ Minor, W. F. & Minor, M. (1981). "Nesting of Red-tailed Hawks and Great Horned Owls in central New York suburban areas" (PDF). Kingbird. 31: 68–76.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bent, A. C. 1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey, Part 1. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 170:295–357.

- ^ Garrigues, Jeff. "Biogeography of Red-tailed hawk". San Francisco State University Department of Geography. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- ^ Smith, E. L., Hoffman, S. W., Stahlecker, D. W., & Duncan, R. B. (1996). "Results of a raptor survey in southwestern New Mexico". J. Raptor Res. 30 (4): 183–188.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - S2CID 86710442.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 1368448.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Chandler, C. R., & Rose, R. K. (1988). "Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Visual and Auditory Stimuli on Avian Mobbing Behavior". Journal of Field Ornithology. 59 (3): 269–277.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISBN 978-1-4615-1531-9

- .

- JSTOR 1364723.

- ^ JSTOR 4086604.

- S2CID 2484938. Archived from the original(PDF) on 13 February 2019.

- doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1989.tb02739.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2019.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lowe, C. 1978. Certain life history aspects of the Red-tailed Hawk, central Oklahoma and interior Alaska. Master's Thesis, Univ. Alaska, Fairbanks.

- ^ Farmer, C. J., Bell, R. J., Drolet, B., Goodrich, L. J., Greenstone, E., Grove, D., & Sodergren, J. (2008). "Trends in autumn counts of migratory raptors in northeastern North America, 1974–2004" (PDF). Series in Ornithology. 3: 179–215.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Castaño R, A. M. & Colorado G.J. (2002). "First records of red-tailed hawk Buteo jamaicensis in Colombia". Cotinga. 18: 102.

- JSTOR 4159454.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 4083962.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 4512919.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Hoffman, S. W., Smith, J. P., & Meehan, T. D. (2002). "Breeding grounds, winter ranges, and migratory routes of raptors in the Mountain West". Journal of Raptor Research. 36 (2): 97–110.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ JSTOR 1365056.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Sherrod, S. K. (1978). "Diets of North American Falconiformes". Raptor Res. 12 (3/4): 49–121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Blumstein, D.T. (1986). The Diets and Breeding Biology of Red-tailed Hawks in Boulder County: 1985 Nesting Season. Colorado Division of Wildlife.

- doi:10.1139/z83-295.

- ^ JSTOR 4163598. Archived from the originalon 6 March 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ S2CID 1726706.

- PMID 28097061.

- ^ JSTOR 3247736.

- ^ Sarasola, J. H., & Negro, J. J. (2004). "Gender determination in the Swainson's Hawk (Buteo swainsoni) using molecular procedures and discriminant function analysis". Journal of Raptor Research. 38 (4): 357–361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - PMID 19946365.

- ^ JSTOR 4083840.

- ^ Marti, C. D., Korpimäki, E., & Jaksić, F. M. (1993). Trophic structure of raptor communities: a three-continent comparison and synthesis. In Current ornithology (pp. 47–137). Springer US.

- ^ Orde, C. J., & Harrell, B. E. (1977). "Hunting techniques and predatory efficiency of nesting Red-tailed Hawks". Journal of Raptor Research. 11: 82–85.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lee, Y. F., & Kuo, Y. M. (2001). "Predation on Mexican free-tailed bats by peregrine falcons and red-tailed hawks". Journal of Raptor Research. 35 (2): 115–123.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ JSTOR 4158291.

- doi:10.1111/mam.12060.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ JSTOR 2388188.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Goss, N. S. (1891). History of the Birds of Kansas. Geo. W. Crane and Co., Topeka, Kansas.

- JSTOR 4161573.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Richter R. (1985). "Red-tailed Hawk drowns Yellow-crowned Night Heron". Florida Field Naturalist. 13: 12–13.

- ^ Turner, Ashley S., L. Mike Conner, and Robert J. Cooper. "Supplemental feeding of northern bobwhite affects red‐tailed hawk spatial distribution." The Journal of Wildlife Management 72.2 (2008): 428–432.

- JSTOR 3504466.

- ^ JSTOR 3627354.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Fisher, Albert Kenrick. The hawks and owls of the United States in their relation to agriculture. No. 3. US Department of Agriculture, Division of Ornithology and Mammalogy, 1893.

- S2CID 253949975.

- JSTOR 4156331.

- .

- S2CID 26871857.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c

Smith, D. G., & Murphy, J. R. (1973). "Breeding ecology of raptors in the eastern Great Basin of Utah". Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series. 18 (3).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Verts, B. J., & Carraway, L. N. (1999). "Thomomys talpoides". Mammalian Species (618): 1–11. JSTOR 3504451.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^

Howard, W., & Childs, H. (1959). "Ecology of pocket gophers with emphasis on Thomomys bottae mewa". Hilgardia. 29 (7): 277–358. doi:10.3733/hilg.v29n07p277.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^

Armitage, K. B. (1981). "Sociality as a life-history tactic of ground squirrels". Oecologia. 48 (1): 36–49. S2CID 31942417.

- S2CID 13802495. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2019.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^

Owings, D. H., Borchert, M., & Virginia, R. (1977). "The behaviour of California ground squirrels". Animal Behaviour. 25: 221–230. S2CID 53158532.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^

Wilson, D. R., & Hare, J. F. (2004). "Animal communication: Ground squirrel uses ultrasonic alarms" (PDF). Nature. 430 (6999): 523. S2CID 4348026.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p

Fitch, H. S., Swenson, F., & Tillotson, D. F. (1946). "Behavior and food habits of the Red-tailed Hawk". The Condor. 48 (5): 205–237. JSTOR 1363939.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^

Tromborg, C. T., & Coss, R. G. (2015). "Isolation rearing reveals latent antisnake behavior in California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus becheeyi) searching for predatory threats" (PDF). Animal Cognition. 18 (4): 855–65. S2CID 17594129.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^

Rickart, E. A. (1987). "Spermophilus townsendii". Mammalian Species. 268: 1–6. doi:10.2307/0.268.1.

- ^ a b c Fitzner, R. E., Rickard, W. H., Cadwell, L. L., & Rogers, L. E. (1981). Raptors of the Hanford site and nearby areas of southcentral Washington (No. PNL-3212). Battelle Pacific Northwest Labs., Richland, WA (USA).

- ^ a b c

Seidensticker, J. C. (1970). "Food of nesting Red-tailed Hawks in south-central Montana". The Murrelet. 51 (3): 38–40. JSTOR 3534043.

- ^

Michener, G. R., & Koeppl, J. W. (1985). "Spermophilus richardsonii". Mammalian Species (243): 1–6. JSTOR 3503990.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d e f g h i j

Luttich, S., Rusch, D. H., Meslow, E. C., & Keith, L. B. (1970). "Ecology of Red-Tailed Hawk Predation in Alberta". Ecology. 51 (2): 190–203. JSTOR 1933655.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c

Errington, P. L., & Breckenridge, W. J. (1938). "Food habits of Buteo hawks in north-central United States". The Wilson Bulletin. 50 (2): 113–121. JSTOR 4156719.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c

Wootton, J. T. (1987). "The Effects of Body Mass, Phylogeny, Habitat, and Trophic Level on Mammalian Age at First Reproduction". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 41 (4): 732–749. S2CID 8217344.

- ^ a b c d e f g Doyle, F. I. (2001). Timing of reproduction by red-tailed hawks, northern goshawks and great horned owls in the Kluane Boreal Forest of Southwestern Yukon. PhD Thesis. University of British Columbia.

- ^ hdl:1811/22576.

- ^ a b Blumstein, D. T. (1989). "Food habits of red-tailed hawks in Boulder County, Colorado". J. Raptor Res. 23: 53–55.

- PMID 12637681.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 253951145.

- JSTOR 3504378.

- JSTOR 3503856.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 85350543.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d e f g Gatto, Angela E.; Grubb, Teryl G.; Chambers, Carol L. (2006). "Red-tailed Hawk dietary overlap with Northern Goshawks on the Kaibab Plateau, Arizona". Journal of Raptor Research. 39 (4): 439–444.

- ^ Millsap, B. A. (1981). Distributional status of falconiformes in westcentral Arizona: with notes on ecology, reproductive success and management. US Bureau of Land Management, Phoenix District Office.

- ^ Smith, Dwight G., and Joseph R. Murphy. "BREEDING RESPONSES OF RAPTORS TO JACKRABBIT DENSITY." Raptor Research 13.1 (1979): 1-14.

- JSTOR 3071790.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Murphy, Robert K. "Prey of nesting red-tailed hawks and great horned owls on Lostwood National Wildlife Refuge, north-western North Dakota." Blue jay 55.3 (1997).

- JSTOR 3504319.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Townsend's Mole in Canada. 0-662-33588-0. Ottawa: Environment Canada. 2003.

- JSTOR 3504286.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 198969062.

- ^ a b c d e "Study of North Virginia Ecology". Fairfax County Public Schools. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- JSTOR 3504148.

- ^ McDonough, C. M., & Loughry, W. J. (2013). The nine-banded armadillo: a natural history (Vol. 11). University of Oklahoma Press.

- ^ Powell, Roger A. "Evolution of black-tipped tails in weasels: predator confusion." The American Naturalist 119.1 (1982): 126–131.

- ^ Santana, Eduardo, and Stanley A. Temple. "Breeding biology and diet of Red-tailed Hawks in Puerto Rico." Biotropica (1988): 151–160.

- ^ Errington, Paul L., and Walter John Breckenridge. "Food habits of Buteo hawks in north-central United States." The Wilson Bulletin 50.2 (1938): 113–121.

- ^ "Red-tailed Hawk vs. Mink". fishers island conservancy. August 2018.

- ^ Platt, Steven G., and Thomas R. Rainwater. "RED-TAILED HAWK PREDATION OF A STRIPED SKUNK." (2012).

- S2CID 13646837.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 42678659.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d Bildstein, K. L. (1987). Behavioral ecology of red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), rough-legged hawks (Buteo lagopus), northern harriers (Circus cyaneus), and American kestrels (Falco sparverius) in south central Ohio (No. 04; USDA, QL696. F3 B5.).

- ^ Barney, M.D. (1959). "Red-tailed hawk killing a lamb". Condor. 61: 157–158.

- ^ Holdermann, D.A. & Holdermann, C.E. (1993). "Immature Red-tailed Hawk captures Montezuma Quail". NMOS Bulletin. 21: 31–33.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rollins, D., Taylor, B. D., Sparks, T. D., Buntyn, R. J., Lerich, S. E., Harveson, L. A., Waddell, T.E. & Scott, C. B. (2009). "Survival of female scaled quail during the breeding season at three sites in the Chihuahuan Desert". In National Quail Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 48.

- ^ a b McCluskey C. (1979). "Red-tailed Hawk preys on adult Sage Grouse in northern Utah". Raptor Research. 13: 123.

- S2CID 44811741.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 35346957.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - doi:10.2173/bna.68

- doi:10.2173/bna.36

- ^ "Sage Grouse Behavior". The Sage Grouse Initiative. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ JSTOR 4160255.

- Cooperative ExtensionPoultry. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00582.x.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 34064989.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 1364279.

- JSTOR 3809423.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Wiley, J. W., & Wiley, B. N. (1979). "The biology of the White-crowned Pigeon". Wildlife Monographs, (64), 3–54.

- JSTOR 4075306.

- doi:10.1016/0006-3207(95)00104-2.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - doi:10.2173/bna.406

- doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00171-X.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Evens, J. G., & Thorne, K. M. (2015). "Case Study, California Black Rail (Laterallus jamaicensis corturniculus)". Science Foundation Chapter 5, Appendix 5.1 in The Baylands and climate change: What can we do?. California State Coastal Conservancy.

- doi:10.2173/bna.154

- S2CID 86248829.

- S2CID 55754017.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Callaghan, C. T., & Brooks, D. M. (2016). "Ecology, behavior, and reproduction of invasive Egyptian Geese (Alopochen aegyptiaca) in Texas". Bulletin of the Texas Ornithological Society. 49: 37–45.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - doi:10.2173/bna.328

- JSTOR 1363880.

- ^ Cherry, M.J., Lane, V.R., Warren, R.J. & Conner, L.M. (2011). "Red-tailed hawk attacks Wild Turkey on bait: Can Baiting Affect Predation Risk?". The Oriole. 77: 19–24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - doi:10.2173/bna.105

- doi:10.2173/bna.31

- ^ a b c d Fisher, A. K. (1893). Hawks and owls of the United States in their relation to agriculture. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Bull. 3. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

- ^ a b Knight, R. L., & Erickson, A. W. (1976). "High incidence of snakes in the diet of nesting red-tailed hawks". Raptor Res. 10: 108–111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - S2CID 86184092.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ JSTOR 4156082.

- ^ Feldman, A., & Meiri, S. (2013). Length–mass allometry in snakes. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 108(1), 161–172.

- PMID 18254921.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Timmerman, W. W. "Home range, habitat use, and behavior of the eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) on the Ordway Preserve." Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 38 (1995): 127-158.

- ^ Heckel, Jens-Ove, D. Clay Sisson, and Charlotte F. Quist. "Apparent fatal snakebite in three hawks." Journal of Wildlife Diseases 30.4 (1994): 616-619.

- S2CID 51943383.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Kendrick, M. M., & Mengak, M. T. (2010). Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon couperi). Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, The University of Georgia.

- ^ Linzey, D.W. & Clifford, M.J. (1981). Snakes of Virginia. Univ. of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, VA.

- ^ Hollingsworth, B. D. (1998). "The systematics of chuckwallas (Sauromalus) with a phylogenetic analysis of other iguanid lizards". Herpetological Monographs, pp. 38–191.

- JSTOR 3893416.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - doi:10.1890/0012-9615(2002)072[0541:MSDSSA]2.0.CO;2.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Powell, R. & Henderson, R.W. (2008). "Avian predators of West Indian reptiles" (PDF). Iguana. 15 (1): 9–12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blázquez, M. Carmen, Ricardo Rodríguez‐Estrella, and Miguel Delibes. "Escape behavior and predation risk of mainland and island spiny‐tailed iguanas (Ctenosaura hemilopha)." Ethology 103.12 (1997): 990-998.

- .

- ^ Fitzpatrick, J. W., & Woolfenden, G. E. (1978). "Red-tailed hawk preys on juvenile gopher tortoise". Florida Field Naturalist. 6: 49.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - S2CID 86140137.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 1364022.

- JSTOR 1363092.

- ^ Fraiola, K. M. S. (2006). Juvenile Epilobocera sinuatifrons growth rates and ontogenetic shifts in feeding in wild populations. PhD Thesis, UGA.

- ^ Tepper, J. M. (2015). "Predators of koi". In 40th World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress, Bangkok, Thailand, 15–18 May 2015. Proceedings book. pp. 349–350. World Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- ^ Stalmaster, M. V. (1980). "Salmon carrion as a winter food source for red-tailed hawks". The Murrelet: 43–44.

- ^ a b c Johnsgard, P. A. (1990). Hawks, eagles, & falcons of North America: biology and natural history. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ JSTOR 1938060.

- JSTOR 27639274.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - JSTOR 3809619.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 86276981.

- S2CID 84426970.

- S2CID 85425945.

- ^ England, A. S., Bechard, M. J., & Houston, C. S. (1997). Swainson's hawk. American Ornithologists' Union.

- ^ Janes, S. W. (1985). INTERSPECIFIC INTERACTIONS AMONG GRASSLAND AND SHRUBSTEPPE RAPTORS: THE SMALLER SPECIES WINS. Behavioral interactions and habitat relations among grassland and shrubsteppe raptors, 7.

- JSTOR 1369063.

- ^ Mindell, D.P. (1983). Nesting raptors in southwestern Alaska: Status, distribution, and aspects of biology. Alaska Technical Report 8. Anchorage: Bureau of Land Management.

- ^ Bohall, P. G., & Collopy, M. W. (1984). "Seasonal abundance, habitat use, and perch sites of four raptor species in north-central Florida". Journal of Field Ornithology. 55: 181–189.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ JSTOR 4085450.

- JSTOR 4157521.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Bildstein, K. L. (1988). "Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus". In Handbook of North American birds. R. S. Palmer, ed. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 251–303

- ISBN 978-0-7136-6565-9.

- ^ Golet, G. H., Golet, H. T., & Colton, A. M. (2003). "Immature Northern Goshawk captures, kills, and feeds on adult-sized wild turkey". Journal of Raptor Research. 37 (4): 337–340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - S2CID 90797670.

- S2CID 3217469.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Smithers, B.L.; Boal, C.W.; Andersen, D.E. (2005). "Northern Goshawk diet in Minnesota: An analysis using video recording systems". Journal of Raptor Research. 39 (3): 264–273.

- ^ Reynolds, R. T., Joy, S.M. & Leslie, D.G. (1994). "Nest productivity, fidelity, and spacing of northern goshawks in northern Arizona". Stud. Avian Biol. 16: 106–113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Boal, C. W. (2005). "Productivity and mortality of northern goshawks in Minnesota". J. Raptor Res. 39 (3): 222–228.

- ^ a b Voous, K.H. 1988. Owls of the Northern Hemisphere. The MIT Press, 0262220350.

- ^ Jaksić, F. M., & Marti, C. D. (1984). Comparative food habits of Bubo owls in Mediterranean-type ecosystems. Condor, 288–296.

- ^ Donázar, J. A., Hiraldo, F., Delibes, M., & Estrella, R. R. (1989). Comparative food habits of the Eagle Owl Bubo bubo and the Great Horned Owl Bubo virginianus in six Palearctic and Nearctic biomes. Ornis Scandinavica, 298–306.

- ^ Cromrich, L. A., Holt, D. W., & Leasure, S. M. (2002). "Trophic niche of North American great horned owls". Journal of Raptor Research. 36 (1): 58–65.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d McInvaille, W. B. (1972). Predator-prey relations and breeding biology of the great horned owl and red-tailed hawk in central Alberta. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- ^ Wilson, P.W. & Grigsby, E.M. (1980). "Red-tailed Hawks Attack Great Horned Owl". Inland Bird Banding. 54: 80.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - JSTOR 4083679.

- ^ JSTOR 4084633.