Red fox

| Red fox Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene – present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Vulpes |

| Species: | V. vulpes

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vulpes vulpes | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Distribution of the red fox native

introduced presence uncertain | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is the largest of the

The red fox originated from smaller-sized ancestors from Eurasia during the Middle Villafranchian period,[5] and colonised North America shortly after the Wisconsin glaciation.[6] Among the true foxes, the red fox represents a more progressive form in the direction of carnivory.[7] Apart from its large size, the red fox is distinguished from other fox species by its ability to adapt quickly to new environments. Despite its name, the species often produces individuals with other colourings, including leucistic and melanistic individuals.[7] Forty-five subspecies are currently recognised,[8] which are divided into two categories: the large northern foxes and the small, basal southern grey desert foxes of Asia and North Africa.[7]

Red foxes are usually found in pairs or small groups consisting of families, such as a

The species has a long history of association with humans, having been extensively hunted as a pest and

Terminology

Males are called tods or dogs, females are called vixens, and young are known as cubs or kits.[14] Although the Arctic fox has a small native population in northern Scandinavia, and while the corsac fox's range extends into European Russia, the red fox is the only fox native to Western Europe, and so is simply called "the fox" in colloquial British English.

Etymology

The word "fox" comes from

The scientific term vulpes derives from the Latin word for fox, and gives the adjectives vulpine and vulpecular.[15]

Evolution

The red fox is considered to be a more specialised form of Vulpes than the

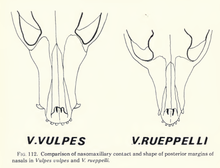

The sister lineage to the red fox is the Rüppell's fox, but the two species are surprisingly closely related through mitochondrial DNA markers, with Rüppell's fox nested inside the lineages of red foxes.[16][17] Such a nesting of one species within another is called paraphyly. Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain this,[16] including (1) recent divergence of Rüppell's fox from a red fox lineage, (2) incomplete lineage sorting, or introgression of mtDNA between the two species. Based on fossil record evidence, the last scenario seems most likely, which is further supported by the clear ecological and morphological differences between the two species.[citation needed]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Origins

The species is Eurasian in origin, and may have evolved from either Vulpes alopecoides or the related Chinese V. chikushanensis, both of which lived during the Middle

Colonisation of North America

Red foxes colonised the North American continent in two waves: before and during the

Although European foxes (V. v. crucigera) were introduced to portions of the United States in the 1900s, recent genetic investigation indicates an absence of European fox mitochondrial haplotypes in any North American populations.

Subspecies

The 3rd edition of Mammal Species of the World[8] listed 45 subspecies as valid. In 2010, a distinct 46th subspecies, the Sacramento Valley red fox (V. v. patwin), which inhabits the grasslands of the Sacramento Valley, was identified through mitochondrial haplotype studies.[28] Castello (2018) recognized 30 subspecies of the Old World red fox and nine subspecies of the North American red fox as valid.[29]

Substantial

Red fox subspecies in Eurasia and North Africa are divided into two categories:[7]

- Northern foxes are large and brightly coloured.

- Southern grey desert foxes include the Asian subspecies V. v. griffithi, V. v. pusilla, and V. v. flavescens. These foxes display transitional features between the northern foxes and other, smaller fox species; their skulls possess more primitive, neotenous traits than the northern foxes[7] and they are much smaller; the maximum sizes attained by southern grey desert foxes are invariably less than the average sizes of northern foxes. Their limbs are also longer and their ears larger.[7]

Red foxes living in Middle Asia show physical traits intermediate to the northern foxes and southern grey desert foxes.[7]

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Trinomial authority (year) | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scandinavian red fox V. v. vulpes ( nominate subspecies )

|

Linnaeus | 1758 | A large subspecies measuring 70–90 cm in length and weighing 5–10 kg; the maximum length of the skull for males is 163.2 mm. The fur is bright red with a strongly developed whitish and yellow ripple on the lower back.[7] | Urals and probably Central and Western Europe

|

alopex (Linnaeus, 1758) communis (Burnett, 1829) |

| British Columbia red fox[34] V. v. abietorum |

Merriam | 1900 | Generally similar to V. v. alascensis, but with a lighter, longer and more slender skull[35] | Southern North-West Territories, northern Alberta, the interior of British Columbia and in the adjoining coastal southeast Alaska (US).[36]

|

sitkaensis (Brass, 1911) |

| Northern Alaskan fox V. v. alascensis |

Merriam | 1900 | A large, long-tailed, small-eared form with golden-fulvous fur[35] | The Andreafsky Wilderness, Alaska, U.S. | |

| Eastern Transcaucasian fox V. v. alpherakyi |

Satunin

|

1906 | A small subspecies weighing 4 kg; its maximum skull length is 132–39 mm in males and 121–26 mm in females. The fur is rusty grey or rusty brown, with a brighter rusty stripe along the spine. The coat is short, coarse and sparse.[7] | Geok Tepe, Aralsk, Kazakhstan

|

|

| Anatolian fox V. v. anatolica |

Thomas | 1920 | Izmir, the Aegean Region, Turkey

|

||

| Arabian red fox V. v. arabica |

Thomas | 1920 | Dhofar and the Hajar Mountains, Oman | ||

| Atlas fox V. v. atlantica |

Wagner | 1841 | The Atlas Mountains, Mila Province, Algeria | algeriensis (Loche, 1858) | |

| Labrador fox V. v. bangsi |

Merriam | 1900 | Similar to V. v. fulva, but with smaller ears and less pronounced black markings on the ears and legs.[35] | ||

| Barbary fox V. v. barbara |

Shaw | 1800 | The Barbary Coast, northwestern Africa | acaab (Cabrera, 1916) | |

| Anadyr fox V. v. beringiana |

Middendorff | 1875 | A large subspecies; it is the most brightly coloured of the Old World red foxes, the fur being saturated bright-reddish and almost lacking the bright ripple along the back and flanks. The coat is fluffy and soft.[7] | The shores of the Bering Strait, northeastern Siberia | anadyrensis (J. A. Allen, 1903) beringensis (Merriam, 1902) |

| Cascade red fox V. v. cascadensis |

Merriam | 1900 | A short-tailed, small-toothed subspecies with yellow rather than fulvous fur; it is the subspecies most likely to produce "cross" colour morphs.[35] | The Skamania County, Washington , U.S.

|

|

| North Caucasian fox V. v. caucasica |

Dinnik | 1914 | A large subspecies; its coat is variable in colour, ranging from reddish to red-grey and nearly grey. The fur is short and coarse. This subspecies could be a hybrid caused by mixing the populations of V. v. stepensis and V. v. karagan.[7] | Near Vladikavkaz, the Caucasus, Russia | |

| European fox V. v. crucigera |

Bechstein | 1789 | A medium-sized subspecies; its yellowish-fulvous or reddish-brown pelt lacks the whitish shading on the upper back. The tail is not grey, as in most other red fox subspecies.[37] It is primarily distinguished from V. v. vulpes by its slightly smaller size, distinctly smaller teeth and widely spaced premolars. Red foxes present in Great Britain (and therefore Australia) are usually ascribed to this subspecies, though many populations there display a great degree of tooth compaction not present in continental European red fox populations.[9] | All of Europe except Scandinavia, the Iberian Peninsula and some islands of the Mediterranean Sea; introduced to Australia and North America | alba (Borkhausen, 1797) cinera (Bechstein, 1801) |

| Trans-Baikal fox V. v. daurica |

Ognev | 1931 | A large subspecies; the colour along its spine is light, dull yellowish-reddish with a strongly developed white ripple and greyish longitudinal stripes on the anterior side of the limbs. The coat is coarse but fluffy.[7] | Kharangoi, 45 km west of Troizkosavsk, Siberia | ussuriensis (Dybowski, 1922) |

| Newfoundland fox V. v. deletrix |

Bangs | 1898 | A very pale-coloured form; its light, straw-yellow fur deepens to golden yellow or buff-fulvous in some places. The tail lacks the usual black basal spot. The hind feet and claws are very large.[35] | St. George's Bay, Newfoundland, Canada | |

| Ussuri fox V. v. dolichocrania |

Ognev | 1926 | Sidemi, southern Ussuri, southeastern Siberia | ognevi (Yudin, 1986) | |

| V. v. dorsalis | J. E. Gray | 1838 | |||

| Turkmenian fox V. v. flavescens |

J. E. Gray | 1838 | A small subspecies with an infantile-looking skull and an overall grey-coloured coat; its body length is 49–57.5 cm and it weighs 2.2–3.2 kg.[7] | Northern Iran | cinerascens (Birula, 1913) splendens (Thomas, 1902) |

| American red fox V. v. fulva |

Desmarest | 1820 | This is a smaller subspecies than V. v. vulpes, with a smaller, sharper face, a shorter tail, a lighter pelt more profusely mixed with whitish and darker limbs.[35] | Eastern Canada and the eastern U.S. | pennsylvanicus (Rhoads, 1894) |

| Afghan red fox V. v. griffithi |

Blyth | 1854 | Slightly smaller than V. v. montana; it has a more extensively hoary and silvered pelt.[38]: 121 | Kandahar, Afghanistan | flavescens (Hutton, 1845) |

| Kodiak fox V. v. harrimani |

Merriam | 1900 | This large subspecies has an enormous tail and coarse, wolf-like fur on the tail and lower back. The hairs on the neck and shoulders are greatly elongated and form a ruff.[35] | Kodiak Island, Alaska, U.S. | |

| South Chinese fox V. v. hoole |

R. Swinhoe | 1870 | [39] | Near Amoy, Fukien , southern China

|

aurantioluteus (Matschie, 1907) lineiventer (R. Swinhoe, 1871) |

| Sardinian fox V. v. ichnusae |

Miller | 1907 | A small subspecies with proportionately small ears.[37] | English Midlands[30] : 6

|

|

| Cyprus fox V. v. indutus |

Miller | 1907 | Cape Pyla, Cyprus | ||

| Yakutsk fox V. v. jakutensis |

Ognev | 1923 | This subspecies is large, but smaller than V. v. beringiana. The back, neck and shoulders are brownish-rusty, while the flanks are bright ocherous reddish-yellow.[7] | The taiga south of Yakutsk, eastern Siberia | sibiricus (Dybowski, 1922) |

| Japanese fox V. v. japonica |

Ognev | 1923 | Japan, except for Hokkaido | ||

| Karaganka fox V. v. karagan |

Erxleben | 1777 | A smaller subspecies than V. v. vulpes; its fur is short, coarse and of a light sandy-yellow or yellowish-grey colour.[7] | The Khirgizia , Russia

|

ferganensis (Ognev, 1926) melanotus (Pallas, 1811) |

| Kenai Peninsula fox V. v. kenaiensis |

Merriam | 1900 | One of the largest North American subspecies; it has softer fur than V. v. harrimani.[35] | The Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, U.S. | |

| Transcaucasian montane fox V. v. kurdistanica |

Satunin | 1906 | A form intermediate in size between V. v. alpheryaki and V. v. caucasica; its fur is pale yellow or light grey, sometimes brownish-reddish and is fluffier and denser than that of the other two Caucasian red fox subspecies.[7] | Northeastern Turkey | alticola (Ognev, 1926) |

| Wasatch Mountains fox V. v. macroura |

Baird | 1852 | This fox is similar to V. v. fulvus, but with a much longer tail, larger hind feet and more extensive blackening of the limbs.[35] | Named for the Wasatch Mountains near the Great Salt Lake, Utah, found in the Rocky Mountains from Colorado and Utah, western Wyoming and Montana through Idaho north to southern Alberta

|

|

| Hill fox V. v. montana |

Pearson

|

1836 | This subspecies is distinguished from V. v. vulpes by its smaller size, proportionately smaller skull and teeth and coarser fur. The hairs on the sole of the feet are copiously mixed with softer, woolly hairs.[38]: 111 | The Himalayas and northern Indian subcontinent | alopex (Blanford, 1888) himalaicus (Ogilby, 1837) |

| Sierra Nevada red fox or High Sierra fox V. v. necator |

Merriam | 1900 | Externally similar to V. v. fulvus; it has a short tail, but cranially it is more like V. v. macroura[35] | The High Sierra , California

|

|

| Nile fox V. v. niloticus |

E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire | 1803 | A small subspecies; it measures 76.7–105.3 cm in body length, 30.2–40.1 cm in tail length and weighs 1.8–3.8 kg. It is ruddy to grey-brown above and darker on the back of the neck. The flanks are greyer and tinged with buff.[40] It is larger than V. v. arabica and V. v. palaestina.[41] | Egypt and Sudan | aegyptiacus (Sonnini, 1816) anubis (Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1833) |

| Turkestan fox V. v. ochroxantha |

Ognev | 1926 | Semirechye, eastern Russian Turkestan , Kirgizia

|

||

| Palestinian fox V. v. palaestina |

Thomas | 1920 | |||

| Korean fox V. v. peculiosa |

Kishida | 1924 | Northeastern China, Southeastern Russia, and Korea | kiyomassai (Kishida and Mori, 1929) | |

| White-footed fox V. v. pusilla |

Blyth | 1854 | Slightly smaller than V. v. griffithii;[38]: 123 it closely resembles the Bengal fox (V. bengalensis) in size, but is distinguished by its longer tail and hind feet.[38]: 129 | The Salt Range, Punjab, Pakistan | leucopus (Blyth, 1854) persicus (Blanford, 1875) |

| Northern plains fox V. v. regalis |

Merriam | 1900 | The largest North American red fox subspecies; it has very large and broad ears and a very long tail. It is a golden-yellow colour with pure black feet.[35] | The Sherburne County, Minnesota , US

|

|

| Nova Scotia fox V. v. rubricosa |

Bangs | 1898 | A large-sized subspecies with a large, broad tail and larger teeth and rostrum than V. v. fulvus; it is the deepest-coloured subspecies.[35] | Digby County, Nova Scotia, Canada | bangsi (Merriam, 1900) deletrix (Bangs, 1898) |

| Ezo red fox V. v. schrencki |

Kishida | 1924 | Sakhalin, Russia and Hokkaido, Japan | ||

| Iberian fox V. v. silacea |

Miller | 1907 | Though equal in size to V. v. vulpes, it has smaller teeth and more widely spaced premolars. The fur is dull buff without any yellowish or reddish tints. The hindquarters are frosted with white and the tail is clear grey in colour.[42] | The Iberian Peninsula | |

| Kurile Islands fox V. v. splendidissima |

Kishida | 1924 | The northern and central Kurile Islands , Russia

|

||

| Steppe red fox V. v. stepensis |

Brauner | 1914 | This subspecies is slightly smaller and more lightly coloured than V. v. crucigera, with shorter, coarser fur. Specimens from the Crimean Mountains have brighter, fluffier and denser fur.[7] | The steppes near Kherson, Ukraine | krymeamontana (Brauner, 1914) crymensis (Brauner, 1914) |

| Tobolsk fox V. v. tobolica |

Ognev | 1926 | This large subspecies has yellowish-rusty or dirty-reddish fur with a well-developed cross and often a black area on the belly. The coat is long and fluffy.[7] | Obdorsk, Tobolsk , Russia

|

|

| North Chinese fox V. v. tschiliensis |

Matschie | 1907 | Slightly larger than V. v. hoole, but unlike other Chinese red foxes, it closely approaches V. v. vulpes in size.[43] | Hebei province , China

|

huli (Sowerby, 1923) |

Description

Build

The red fox has an elongated body and relatively short limbs. The tail, which is longer than half the body length

Their

Dimensions

Red foxes are the largest species of the genus Vulpes.[46] However, relative to dimensions, red foxes are much lighter than similarly sized dogs of the genus Canis. Their limb bones, for example, weigh 30 percent less per unit area of bone than expected for similarly sized dogs.[47] They display significant individual, sexual, age and geographical variation in size. On average, adults measure 35–50 cm (14–20 in) high at the shoulder and 45–90 cm (18–35 in) in body length with tails measuring 30–55.5 cm (11.8–21.9 in). The ears measure 7.7–12.5 cm (3.0–4.9 in) and the hind feet 12–18.5 cm (4.7–7.3 in). Weights range from 2.2–14 kg (4.9–30.9 lb), with vixens typically weighing 15–20% less than males.[48][49] Adult red foxes have skulls measuring 129–167 mm (5.1–6.6 in), while those of vixens measure 128–159 mm (5.0–6.3 in).[7] The forefoot print measures 60 mm (2.4 in) in length and 45 mm (1.8 in) in width, while the hind foot print measures 55 mm (2.2 in) long and 38 mm (1.5 in) wide. They trot at a speed of 6–13 km/h (3.7–8.1 mph), and have a maximum running speed of 50 km/h (31 mph). They have a stride of 25–35 cm (9.8–13.8 in) when walking at a normal pace.[47]: 36 North American red foxes are generally lightly built, with comparatively long bodies for their mass and have a high degree of sexual dimorphism. British red foxes are heavily built, but short, while continental European red foxes are closer to the general average among red fox populations.[50] The largest red fox on record in Great Britain was a 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) long male, that weighed 17.2 kg (38 lb), killed in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, in early 2012.[51]

Fur

The winter fur is dense, soft, silky and relatively long. For the northern foxes, the fur is very long, dense and fluffy, but it is shorter, sparser and coarser in southern forms.

Colour morphs

Atypical colouration in the red fox usually represents stages toward full melanism,[7] and mostly occurs in cold regions.[10]

| Colour morph | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Red |

|

The typical colouration (see fur above) |

| Smokey | The rump and spine is brown or grey with light yellowish bands on the guard hairs. The cross on the shoulders is brown, rusty brown or reddish-brown. The limbs are brown.[7] | |

Cross

|

|

The fur has a darker colouration than the colour morph listed directly above. The rump and lower back are dark brown or dark grey, with varying degrees of silver on the guard hairs. The cross on the shoulders is black or brown, sometimes with light silvery fur. The head and feet are brown.[7] |

| Blackish-brown | The melanistic colour morph of the Eurasian red foxes. Has blackish-brown or black skin with a light brownish tint. The skin area usually has a variable admixture of silver. Reddish hairs are either completely absent or in small quantities.[7] | |

| Silver |

|

The melanistic colour morph of the North American red foxes, but introduced to the Old World by the fur trade. Characterised by pure black colour with skin that usually has a variable admixture of silver (covering 25–100% of the skin area)[7] |

| Platinum |

|

Distinguished from the silver colour morph by its pale, almost silvery-white fur with a bluish cast[13]: 251 |

| Amber |

|

|

| Samson |

|

Distinguished by its woolly pelt, which lacks guard hairs[13]: 230 |

Senses

Red foxes have

Scent glands

Red foxes have a pair of

Distribution and habitat

The red fox is a wide-ranging species. Its range covers nearly 70,000,000 km2 (27,000,000 sq mi) including as far north as the Arctic Circle. It occurs all across Europe, in Africa north of the Sahara Desert, throughout Asia apart from extreme Southeast Asia, and across North America apart from most of the southwestern United States and Mexico. It is absent in Greenland, Iceland, the Arctic islands, the most northern parts of central Siberia, and in extreme deserts.[1] It is not present in New Zealand and is classed as a "prohibited new organism" under the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, which does not allow import.[55]

Australia

In Australia, estimates in 2012 indicated that there were more than 7.2 million red foxes,

The red fox has been implicated in the extinction or decline of several native Australian species, particularly those of the family

Sardinia, Italy

The origin of the ichnusae subspecies in Sardinia, Italy is uncertain, as it is absent from Pleistocene deposits in their current homeland. It is possible it originated during the Neolithic following its introduction to the island by humans. It is likely then that Sardinian fox populations stem from repeated introductions of animals from different localities in the Mediterranean. This latter theory may explain the subspecies' phenotypic diversity.[21]

Behaviour

Social and territorial behaviour

Red foxes either establish stable home ranges within particular areas or are itinerant with no fixed abode.

Reproduction and development

Red foxes reproduce once a year in spring. Two months prior to

The average litter size consists of four to six kits, though litters of up to 13 kits have occurred.[7] Large litters are typical in areas where fox mortality is high.[47]: 93 Kits are born blind, deaf and toothless, with dark brown fluffy fur. At birth, they weigh 56–110 g (2.0–3.9 oz) and measure 14.5 cm (5.7 in) in body length and 7.5 cm (3.0 in) in tail length. At birth, they are short-legged, large-headed and have broad chests.[7] Mothers remain with the kits for 2–3 weeks, as they are unable to thermoregulate. During this period, the fathers or barren vixens feed the mothers.[9] Vixens are very protective of their kits, and have been known to even fight off terriers in their defence.[30]: 21–22 If the mother dies before the kits are independent, the father takes over as their provider.[30]: 13 The kits' eyes open after 13–15 days, during which time their ear canals open and their upper teeth erupt, with the lower teeth emerging 3–4 days later.[7] Their eyes are initially blue, but change to amber at 4–5 weeks. Coat colour begins to change at three weeks of age, when the black eye streak appears. By one month, red and white patches are apparent on their faces. During this time, their ears erect and their muzzles elongate.[9] Kits begin to leave their dens and experiment with solid food brought by their parents at the age of 3–4 weeks. The lactation period lasts 6–7 weeks.[7] Their woolly coats begin to be coated by shiny guard hairs after 8 weeks.[9] By the age of 3–4 months, the kits are long-legged, narrow-chested and sinewy. They reach adult proportions at the age of 6–7 months.[7] Some vixens may reach sexual maturity at the age of 9–10 months, thus bearing their first litters at one year of age.[7] In captivity, their longevity can be as long as 15 years, though in the wild they typically do not survive past 5 years of age.[70]

Denning behaviour

Outside the

Communication

Body language

Red fox body language consists of movements of the ears, tail and postures, with their body markings emphasising certain gestures. Postures can be divided into aggressive/dominant and fearful/submissive categories. Some postures may blend the two together.[47]: 42–43 Inquisitive foxes will rotate and flick their ears whilst sniffing. Playful individuals will perk their ears and rise on their hind legs. Male foxes courting females, or after successfully evicting intruders, will turn their ears outwardly, and raise their tails in a horizontal position, with the tips raised upward. When afraid, red foxes grin in submission, arching their backs, curving their bodies, crouching their legs and lashing their tails back and forth with their ears pointing backwards and pressed against their skulls. When merely expressing submission to a dominant animal, the posture is similar, but without arching the back or curving the body. Submissive foxes will approach dominant animals in a low posture, so that their muzzles reach up in greeting. When two evenly matched foxes confront each other over food, they approach each other sideways and push against each other's flanks, betraying a mixture of fear and aggression through lashing tails and arched backs without crouching and pulling their ears back without flattening them against their skulls. When launching an assertive attack, red foxes approach directly rather than sideways, with their tails aloft and their ears rotated sideways.[47] During such fights, red foxes will stand on each other's upper bodies with their forelegs, using open mouthed threats. Such fights typically only occur among juveniles or adults of the same sex.[9]

Vocalisations

Red foxes have a wide vocal range, and produce different sounds spanning five octaves, which grade into each other.[47]: 28 Recent analyses identify 12 different sounds produced by adults and 8 by kits.[9] The majority of sounds can be divided into "contact" and "interaction" calls. The former vary according to the distance between individuals, while the latter vary according to the level of aggression.[47]: 28

- Contact calls: The most commonly heard contact call is a three to five syllable barking "wow wow wow" sound, which is often made by two foxes approaching one another. This call is most frequently heard from December to February (when they can be confused with the territorial calls of tawny owls). The "wow wow wow" call varies according to individual; captive foxes have been recorded to answer pre-recorded calls of their pen-mates, but not those of strangers. Kits begin emitting the "wow wow wow" call at the age of 19 days, when craving attention. When red foxes draw close together, they emit trisyllabic greeting warbles similar to the clucking of chickens. Adults greet their kits with gruff huffing noises.[47]: 28

- Interaction calls: When greeting one another, red foxes emit high pitched whines, particularly submissive animals. A submissive fox approached by a dominant animal will emit a ululating siren-like shriek. During aggressive encounters with conspecifics, they emit a throaty rattling sound, similar to a ratchet, called "gekkering". Gekkering occurs mostly during the courting season from rival males or vixens rejecting advances.[47]: 28

Another call that does not fit into the two categories is a long, drawn-out, monosyllabic "waaaaah" sound. As it is commonly heard during the breeding season, it is thought to be emitted by vixens summoning males. When danger is detected, foxes emit a monosyllabic bark. At close quarters, it is a muffled cough, while at long distances it is sharper. Kits make warbling whimpers when nursing, these calls being especially loud when they are dissatisfied.[47]: 28

Ecology

Diet, hunting and feeding behaviour

Red foxes are

Red foxes are implicated in the predation of

While the popular consensus is that

Red foxes prefer to hunt in the early morning hours before sunrise and late evening.[7] Although they typically forage alone, they may aggregate in resource-rich environments.[70] When hunting mouse-like prey, they first pinpoint their prey's location by sound, then leap, sailing high above their quarry, steering in mid-air with their tails, before landing on target up to 5 m (16 ft) away.[1] They typically only feed on carrion in the late evening hours and at night.[7] They are extremely possessive of their food and will defend their catches from even dominant animals.[47]: 58 Red foxes may occasionally commit acts of surplus killing; during one breeding season, four red foxes were recorded to have killed around 200 black-headed gulls each, with peaks during dark, windy hours when flying conditions were unfavourable. Losses to poultry and penned game birds can be substantial because of this.[9][47]: 164 Red foxes seem to dislike the taste of moles, but will nonetheless catch them alive and present them to their kits as playthings.[47]: 41

A 2008–2010 study of 84 red foxes in the Czech Republic and Germany found that successful hunting in long vegetation or under snow appeared to involve an alignment of the red fox with the Earth's magnetic field.[79][80]

Enemies and competitors

Red foxes typically dominate other fox species. Arctic foxes generally escape competition from red foxes by living farther north, where food is too scarce to support the larger-bodied red species. Although the red species' northern limit is linked to the availability of food, the Arctic species' southern range is limited by the presence of the former. Red and Arctic foxes were both introduced to almost every island from the Aleutian Islands to the Alexander Archipelago during the 1830s–1930s by fur companies. The red foxes invariably displaced the Arctic foxes, with one male red fox having been reported to have killed off all resident Arctic foxes on a small island in 1866.[47] Where they are sympatric, Arctic foxes may also escape competition by feeding on lemmings and flotsam rather than voles, as favoured by red foxes. Both species will kill each other's kits, given the opportunity.[7] Red foxes are serious competitors of corsac foxes, as they hunt the same prey all year. The red species is also stronger, is better adapted to hunting in snow deeper than 10 cm (3.9 in) and is more effective in hunting and catching medium-sized to large rodents. Corsac foxes seem to only outcompete red foxes in semi-desert and steppe areas.[7][81] In Israel, Blanford's foxes escape competition with red foxes by restricting themselves to rocky cliffs and actively avoiding the open plains inhabited by red foxes.[47]: 84–85 Red foxes dominate kit and swift foxes. Kit foxes usually avoid competition with their larger cousins by living in more arid environments, though red foxes have been increasing in ranges formerly occupied by kit foxes due to human-induced environmental changes. Red foxes will kill both species and compete with them for food and den sites.[10] Grey foxes are exceptional, as they dominate red foxes wherever their ranges meet. Historically, interactions between the two species were rare, as grey foxes favoured heavily wooded or semiarid habitats as opposed to the open and mesic ones preferred by red foxes. However, interactions have become more frequent due to deforestation, allowing red foxes to colonise grey fox-inhabited areas.[10]

Wolves may kill and eat red foxes in disputes over carcasses.[7][82] In areas in North America where red fox and coyote populations are sympatric, red fox ranges tend to be located outside coyote territories. The principal cause of this separation is believed to be active avoidance of coyotes by the red foxes. Interactions between the two species vary in nature, ranging from active antagonism to indifference. The majority of aggressive encounters are initiated by coyotes, and there are few reports of red foxes acting aggressively toward coyotes except when attacked or when their kits were approached. Foxes and coyotes have sometimes been seen feeding together.[83] In Israel, red foxes share their habitat with golden jackals. Where their ranges meet, the two canids compete due to near-identical diets. Red foxes ignore golden jackal scents or tracks in their territories and avoid close physical proximity with golden jackals themselves. In areas where golden jackals become very abundant, the population of red foxes decreases significantly, apparently because of competitive exclusion.[84] There is however one record of multiple red foxes interacting peacefully with a golden jackal in southwestern Germany.[85]

Red foxes dominate

Red foxes may kill small

Red foxes may compete with striped hyenas on large carcasses. Red foxes may give way to striped hyenas on unopened carcasses, as the latter's stronger jaws can easily tear open flesh that is too tough for red foxes. Red foxes may harass striped hyenas, using their smaller size and greater speed to avoid the hyena's attacks. Sometimes, red foxes seem to deliberately torment striped hyenas even when there is no food at stake. Some red foxes may mis-time their attacks and are killed.[47]: 77–79 Red fox remains are often found in striped hyena dens and striped hyenas may steal red foxes from traps.[7]

In Eurasia, red foxes may be preyed upon by leopards, caracals and Eurasian lynxes. The Eurasian lynxes chase red foxes into deep snow, where their long legs and larger paws give them an advantage over red foxes, especially when the depth of the snow exceeds one meter.[7] In the Velikoluksky District in Russia, red foxes are absent or are seen only occasionally where Eurasian lynxes establish permanent territories.[7] Researchers consider Eurasian lynxes to represent considerably less danger to red foxes than wolves do.[7] North American felid predators of red foxes include cougars, Canada lynxes and bobcats.[44]

Red foxes compete with various birds of prey such as common buzzards (Buteo buteo) and northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis) and even steal their kills.[89][90] In turn, golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) regularly takes young red foxes and prey on adults if needed.[91][92] Other large eagles such as wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax), eastern imperial eagles (Aquila heliaca), white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla), and steller's sea eagles (Haliaeetus pelagicus) have also been known to kill red foxes less frequently.[93][94][95][96][97] Additionally, large owls such as Eurasian eagle-owls (Bubo bubo) and snowy owls (Bubo scandiacus) will prey on young foxes, and adults on exceptional occasions.[98][99][100]

Diseases and parasites

Red foxes are the most important

Red foxes are not readily prone to infestation with

Up to 60

Relationships with humans

In folklore, religion and mythology

Red foxes feature prominently in the folklore and mythology of human cultures with which they are sympatric. In Greek mythology, the Teumessian fox,[106] or Cadmean vixen, was a gigantic fox that was destined never to be caught. The fox was one of the children of Echidna.[107]

In

Chinese folk tales tell of fox-spirits called

The cunning Fox is commonly found in

Hunting

The earliest historical records of fox hunting come from the 4th century BC;

The grays furnished more fun, the reds more excitement. The grays did not run so far, but usually kept near home, going in a circuit of six or eight miles. 'An old red, generally so called irrespective of age, as a tribute to his prowess, might lead the dogs all day, and end by losing them as evening fell, after taking them a dead stretch for thirty miles. The capture of a gray was what men boasted of; a chase after 'an old red' was what they 'yarned' about.[113]

Red foxes are still widely persecuted as pests, with human-caused deaths among the highest causes of mortality in the species. Annual red fox kills are: UK 21,500–25,000 (2000); Germany 600,000 (2000–2001); Austria 58,000 (2000–2001); Sweden 58,000 (1999–2000); Finland 56,000 (2000–2001); Denmark 50,000 (1976–1977); Switzerland 34,832 (2001); Norway 17,000 (2000–2001); Saskatchewan (Canada) 2,000 (2000–2001); Nova Scotia (Canada) 491 (2000–2001); Minnesota (US) 4,000–8,000 (average annual trapping harvest 2002–2009);[114] New Mexico (US) 69 (1999–2000).[86]

Fur use

Red foxes are among the most important

North American red foxes, particularly those of northern Alaska, are the most valued for their fur, as they have guard hairs of a silky texture which, after dressing, allow the wearer unrestricted mobility. Red foxes living in southern Alaska's coastal areas and the Aleutian Islands are an exception, as they have extremely coarse pelts that rarely exceed one-third of the price of their northern Alaskan cousins.[13]: 231 Most European peltries have coarse-textured fur compared to North American varieties. The only exceptions are the Nordic and Far Eastern Russian peltries, but they are still inferior to North American peltries in terms of silkiness.[13]: 235

Livestock and pet predation

Red foxes may on occasion prey on lambs. Usually, lambs targeted by red foxes tend to be physically weakened specimens, but not always. Lambs belonging to small breeds, such as the Scottish Blackface, are more vulnerable than larger breeds, such as the Merino. Twins may be more vulnerable to red foxes than singlets, as ewes cannot effectively defend both simultaneously. Crossbreeding small, upland ewes with larger, lowland rams can cause difficult and prolonged labour for ewes due to the heaviness of the resulting offspring, thus making the lambs more at risk to red fox predation. Lambs born from gimmers (ewes breeding for the first time) are more often killed by red foxes than those of experienced mothers, who stick closer to their young.[47]: 166–167

Red foxes may prey on domestic rabbits and guinea pigs if they are kept in open runs or are allowed to range freely in gardens. This problem is usually averted by housing them in robust hutches and runs. Urban red foxes frequently encounter cats and may feed alongside them. In physical confrontations, the cats usually have the upper hand. Authenticated cases of red foxes killing cats usually involve kittens. Although most red foxes do not prey on cats, some may do so and may treat them more as competitors rather than food.[47]: 180–181

Taming and domestication

In their unmodified wild state, red foxes are generally unsuitable as pets.[116] Many supposedly abandoned kits are adopted by well-meaning people during the spring period, though it is unlikely that vixens would abandon their young. Actual orphans are rare and the ones that are adopted are likely kits that simply strayed from their den sites.[117] Kits require almost constant supervision; when still suckling, they require milk at four-hour intervals day and night. Once weaned, they may become destructive to leather objects, furniture and electric cables.[47]: 56 Though generally friendly toward people when young, captive red foxes become fearful of humans, save for their handlers, once they reach 10 weeks of age.[47]: 61 They maintain their wild counterparts' strong instinct of concealment and may pose a threat to domestic birds, even when well-fed.[30]: 122 Although suspicious of strangers, they can form bonds with cats and dogs, even ones bred for fox hunting. Tame red foxes were once used to draw ducks close to hunting blinds.[30]: 132–133

White to black individual red foxes have been selected and raised on fur farms as "

Urban red foxes

Distribution

Red foxes have been exceedingly successful in colonising built-up environments, especially lower-density suburbs,

In 2006, it was estimated that there were 10,000 red foxes in London.[121] City-dwelling red foxes may have the potential to consistently grow larger than their rural counterparts as a result of abundant scraps and a relative lack of predators. In cities, red foxes may scavenge food from litter bins and bin bags, although much of their diet is similar to rural red foxes.[citation needed]

Behaviour

Urban red foxes are most active at dusk and dawn, doing most of their hunting and scavenging at these times. It is uncommon to spot them during the day, but they can be caught sunbathing on roofs of houses or sheds. Urban red foxes will often make their homes in hidden and undisturbed spots in urban areas as well as on the edges of a city, visiting at night for sustenance. They sleep at night in dens. While urban red foxes will scavenge successfully in the city (and the red foxes tend to eat anything that humans eat) some urban residents will deliberately leave food out for the animals, finding them endearing. Doing this regularly can attract urban red foxes to one's home; they can become accustomed to human presence, warming up to their providers by allowing themselves to be approached and in some cases even played with, particularly young kits.[120]

Urban red fox control

Urban red foxes can cause problems for local residents. They have been known to steal chickens, disrupt rubbish bins and damage gardens. Most complaints about urban red foxes made to local authorities occur during the breeding season in late January/early February or from late April to August when the new kits are developing.[120] In the U.K., hunting red foxes in urban areas is banned and shooting them in an urban environment is not suitable. One alternative to hunting urban red foxes has been to trap them, which appears to be a more viable method.[122] However, killing red foxes has little effect on the population in an urban area; those that are killed are very soon replaced, either by new kits during the breeding season or by other red foxes moving into the territory of those that were killed. A more effective method of urban red fox control is to deter them from the specific areas they inhabit. Deterrents such as creosote, diesel oil, or ammonia can be used. Cleaning up and blocking access to den locations can also discourage an urban red fox's return.[120]

Relationship between urban and rural red foxes

In January 2014 it was reported that "Fleet", a relatively tame urban red fox tracked as part of a wider study by the

-

An urban red fox crossing a street

-

An urban red fox in central London

-

An urban red fox eating from a bag of biscuits in Dorset, England

-

"Fleet", the urban red fox from the BBC TV series Winterwatch

-

An urban red fox with a discarded KFC bag

References

- ^ . Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Vulpes vulpes". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). "Canis Vulpes". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. Tomus I (decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 40.

- ^ "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Invasive Species Specialist Group. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Kurtén, Björn (1968). Pleistocene Mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ^ ISBN 9780231037334.

- ^ ISBN 978-1886106819.

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- ^ ISBN 978-0906282656.

- ^ ISBN 9780801874161.

- ^ "Red Fox Predators". Wildlife Online. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- S2CID 39202154.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bachrach, M. (1953). Fur: A Practical Treatise (Third ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ "10 Fascinating Facts About Foxes (With Photos)". PETA UK. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Vulpine". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 16341006.

- ^ PaleoDatabase collection No. 35369 Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, authorized by Alan Turner, Liverpool John Moores University. Entry by H. O'Regan, 8 December 2003

- ^ David M. Alba, Saverio Bartolini Lucenti, Joan Madurell Malapeira, 2021, Middle Pleistocene fox from the Vallparadís Section (Vallès-Penedès Basin, NE Iberian Peninsula) and the earliest records of the extant red fox Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, Vol.127, pp.179-187, DOI:10.13130/2039-4942/15229, Retrieved on 26 October 2021

- ^ a b Spagnesi & De Marina Marinis 2002, p. 222

- ^ S2CID 11518843. Archived from the original(PDF) on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- S2CID 25466489.

- ISBN 0931079055.

- .

- S2CID 2995171.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Castello, Jose, 2018. Canids of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dale, Thomas Francis (1906). The Fox. London, New York, Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- PMID 21774815.

- PMID 23738594.

- from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Preble, Edward Alexander (1908). "Mammals". A biological investigation of the Athabaska-Mackenzie region. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 217.

- ^ ISBN 9780665167928.

- ISBN 9781602231160.

- ^ a b Spagnesi & De Marina Marinis 2002, p. 221

- ^ Pocock, Reginald Innes (1941). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma: Mammalia Volume 2, Carnivora: Aeluroidea, Arctoidea. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Allen, G. M. (1938). The mammals of China and Mongolia. Volume 1. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

- ISBN 978-977-416-254-1.

- ^ a b Osborn, Dale J. & Helmy, Ibrahim (1980). The Contemporary Land Mammals of Egypt (including Sinai). Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 376, 679. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Miller, Gerrit Smith (1912). Catalogue of the Mammals of Western Europe (Europe Exclusive of Russia) in the Collection of the British Museum, British Museum (Natural History). Department of Zoology.

- ^ Allen 1938, p. 353

- ^ a b c Larivière, Serge & Pasitschniak-Arts, Maria (1996). Vulpes vulpes (PDF). American Society of Mammalogists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, pp. 132–133

- ^ Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 129

- ^ ISBN 9780044401995.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ISBN 0789477645

- ^ Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 130

- ^ Wilkes, David (5 March 2012). "'Largest fox killed in UK' shot on Aberdeenshire farm". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- S2CID 87183522.

- ^ Albone, E. S. & Grönnerberg, T. O. "Lipids of the anal sac secretions of the red fox, Vulpes vulpes and of the lion, Panthera leo". Journal of Lipid Research. 18.4 (1977): 474–479.

- S2CID 35030583 – via SpringerLink.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 2003 – Schedule 2 Prohibited new organisms". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "Impacts of Feral Animals". Game Council of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- S2CID 54100368.

- .

- ISBN 0731364244. Archived(PDF) from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-521-68660-0.)

- ^ "Latest Physical Evidence of Foxes in Tasmania". Department of Primary Industries and Water, Tasmania website. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- S2CID 15328275.

- ISBN 978-0-19-850796-3.

- S2CID 36332457.

- PMID 10321819.

- S2CID 254144483.

- ISBN 978-0-520-25378-0.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-15227-1.

- ^ Holland, Jennifer S. (July 2011). "40 winks?". National Geographic. 220 (1).

- ISSN 1616-5047.

- ISSN 0003-3472.

- ^ Fox, David L. (2007). "Vulpes vulpes Red fox". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Asa, C. S. & Mech, D. (1995). "A review of the sensory organs in wolves and their importance to life history," in Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World eds. Carbyn, L. D.; Fritts, S. H. & Seip, D. R. (Edmonton: Canadian Circumpolar Institute): 287–291.

- ^ Osterholm, H. (1964). "The significance of distance reception in the feeding behaviour of fox (Vulpes vulpes L.)". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 106 1–31.

- ^ Yong, Ed (11 January 2011). "Foxes use the Earth's magnetic field as a targeting system - Not Exactly Rocket Science". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- PMID 21227977.

- ^ Heptner & Naumov 1998, pp. 453–454

- ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- JSTOR 1381437. Archived from the originalon 14 November 2007.

- (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- .

- ^ a b c Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 134

- ISBN 978-1886106819.

- ISBN 978-1886106819.

- ^ Jankowiak, L. & Tryjanowski, P. (2013). "Cooccurrence and food niche overlap of two common predators (red fox Vulpes vulpes and common buzzard Buteo buteo) in an agricultural landscape". Turkish Journal of Zoology. 37 (2): 157–162.

- ^ Ziesemer, F. (1981). "Methods of assessing goshawk predation". Understanding the goshawk, 144–150.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-1420-9.

- ^ Sulkava, Seppo, et al. "Changes in the diet of the Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos and small game populations in Finland in 1957-96." Ornis Fennica 76 (1999): 1-16.

- ^ Lewis, C. F. (1957). Wedge-tailed eagle takes a fox. Victorian Naturalist, 74, 89-90.

- ^ Heptner, Vladimir G., ed. Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume 2 Part 2 Carnivora (Hyenas and Cats). Vol. 2. Brill, 1989.

- ^ Vrezec, A.; Bordjan, D.; Perušek, M. & Hudoklin, A. (2009). "Population and ecology of the White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) and its conservation status in Slovenia". Denisia. 27: 103–114.

- ^ Utekhina, I.; Potapov, E. & McGrady, M.J. (2000). "Diet of the Steller's Sea Eagle in the northern Sea of Okhotsk". In Ueta, M. & McGrady, M.J. (eds.). First Symposium on Steller's and White-tailed Sea Eagles in East Asia. Tokyo, Japan: Wild Bird Society of Japan. pp. 71–92.

- ^ Larivière, S., & Pasitschniak-Arts, M. (1996). Vulpes vulpes. Mammalian species, (537), 1-11.

- ^ "Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) - Information, Pictures, Sounds". The Owl Pages. 23 October 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Skrifter. (1963). Norway: I Kommisjon Hos Jacob Dybwad.

- ^ Dixon, Charles C. (1970). "Red Fox Predated by Snowy Owl". Blue Jay. 33 (2).

- PMID 23340229.

- PMID 36941973.

- PMID 691132.

- PMID 26624401.

- PMID 31286360.

- Teumessos"; Teumessos was an ancient city in Boeotia.

- ISBN 978-1-86189-297-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-4524-2.

- ^ Goff, Janet (1997). "Foxes in Japanese culture: Beautiful or beastly?" (PDF). Japan Quarterly. 44 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-8248-2102-9.

- ISBN 978-1-86105-831-7.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-533-9.

- ^ a b c Potts, Allen (1912). Fox Hunting in America. Washington: The Carnahan Press. pp. 7, 38. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Dexter, Margaret (8 December 2009). Trapping Harvest Statistics (PDF). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. p. 282 (Table 5). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "NAFA February 2013 Fur Auction Results". Trapping Today. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Jones, Lucy (7 May 2016). "Why we love keeping foxes at home - despite the smell". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Karim, Fariha (8 September 2016). "Why having Mr Fox to stay is not such a fantastic idea after all". The Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- S2CID 120981396. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Urban foxes: Overview". The fox website. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0905483474.

- ^ "10,000 Foxes Roam London". National Geographic. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Fieldsports Britain: How to call in great big bucks". Fieldsports Channel. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021.

- ^ "BBC Two - Winterwatch, Urban Fox Diary: Part 2". BBC. 23 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Fleet the Sussex fox breaks British walking record". BBC. 22 January 2014. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

Further reading

- Osborn, Dale. J. & Helmy, Ibrahim (1980). "The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai)". Fieldiana. New Series (5). Field Museum of Natural History.

- Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Hoffman, Michael & MacDonald, David W. (2004). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs – 2004 Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISBN 978-2-8317-0786-0. Archived from the originalon 6 October 2011.

- Spagnesi, Mario & De Marina Marinis, Maria (2002). "Mammiferi d'Italia". Quaderni di Conservazione della Natura. ISSN 1592-2901.

External links

- "Vulpes vulpes (Linnaeus, 1758)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- Red Fox, National Geographic

- Natural History of the Red Fox, Wildlife Online

- Sacramento Valley red fox info1

- Red Fox, Fletcher Wildlife Garden