Red panda

| Red panda Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ailuridae |

| Genus: | Ailurus F. Cuvier, 1825 |

| Species: | A. fulgens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ailurus fulgens F. Cuvier, 1825

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Range of the red panda | |

The red panda (Ailurus fulgens), also known as the lesser panda, is a small mammal native to the eastern Himalayas and southwestern China. It has dense reddish-brown fur with a black belly and legs, white-lined ears, a mostly white muzzle and a ringed tail. Its head-to-body length is 51–63.5 cm (20.1–25.0 in) with a 28–48.5 cm (11.0–19.1 in) tail, and it weighs between 3.2 and 15 kg (7.1 and 33.1 lb). It is well adapted to climbing due to its flexible joints and curved semi-retractile claws.

The red panda was formally described in 1825. The two currently recognised subspecies, the Himalayan and the Chinese red panda, genetically diverged about 250,000 years ago. The red panda's place on the evolutionary tree has been debated, but modern genetic evidence places it in close affinity with raccoons, weasels, and skunks. It is not closely related to the giant panda, which is a bear, though both possess elongated wrist bones or "false thumbs" used for grasping bamboo. The evolutionary lineage of the red panda (Ailuridae) stretches back around 25 to 18 million years ago, as indicated by extinct fossil relatives found in Eurasia and North America.

The red panda inhabits

Community-based conservation programmes have been initiated in Nepal, Bhutan and northeastern India; in China, it benefits from nature conservation projects. Regional captive breeding programmes for the red panda have been established in zoos around the world. It is featured in animated movies, video games, comic books and as the namesake of companies and music bands.

Etymology

The origin of the name panda is uncertain, but one of the most likely theories is that it derived from the Nepali word "ponya".[3] The word पञ्जा pajā or पौँजा pañjā means "ball of the foot" and "claws".[4] The Nepali words "nigalya ponya" has been translated as "bamboo footed" and is thought to be the red panda's Nepali name; in English, it was simply called panda, and was the only animal known under this name for more than 40 years; it became known as the red panda or lesser panda to distinguish it from the giant panda, which was formally described and named in 1869.[3]

The genus name Ailurus is adopted from the

Taxonomy

The red panda was

Subspecies and species

The modern red panda is the only recognised species in the genus Ailurus. It is traditionally divided into two subspecies: the Himalayan red panda (A. f. fulgens) and the Chinese red panda (A. f. styani). The Himalayan subspecies has a straighter profile, a lighter coloured forehead and ochre-tipped hairs on the lower back and rump. The Chinese subspecies has a more curved forehead and sloping snout, a darker coat with a less white face and more contrast between the tail rings.[11]

In 2020, results of a genetic analysis of red panda samples showed that the red panda populations in the Himalayas and China were separated about 250,000 years ago. The researchers suggested that the two subspecies should be treated as distinct species. Red pandas in southeastern Tibet and northern Myanmar were found to be part of styani, while those of southern Tibet were of fulgens in the strict sense.

Phylogeny

The placement of the red panda on the

| Six genes from 76 Carnivora species[16] |

|---|

| 46 genes from 75 musteloid species[17] |

|---|

| Mitogenomes from 220 mammal species[18] |

|---|

Fossil record

The family Ailuridae appears to have evolved in Europe in either the

Later and more

The earliest fossil record of the modern genus Ailurus dates no earlier than the Pleistocene and appears to have been limited to Asia. The modern red panda's lineage became adapted for a specialised bamboo diet, having molar-like premolars and more elevated cusps.[21] The false thumb would secondarily gain a function in feeding.[19][20]

Genomics

Analysis of 53 red panda samples from Sichuan and Yunnan showed a high level of

Description

The red panda's

The red panda has a relatively small head, though proportionally larger than in similarly sized raccoons, with a reduced snout and triangular ears, and nearly evenly lengthed limbs.[28][29] It has a head-body length of 51–63.5 cm (20.1–25.0 in) with a 28–48.5 cm (11.0–19.1 in) tail. The Himalayan red panda is recorded to weigh 3.2–9.4 kg (7.1–20.7 lb), while the Chinese red panda weighs 4–15 kg (8.8–33.1 lb) for females and 4.2–13.4 kg (9.3–29.5 lb) for males.[28] It has five curved digits on each foot, each with curved semi-retractile claws that aid in climbing.[29] The pelvis and hindlimbs have flexible joints, adaptations for an arboreal quadrupedal lifestyle.[31] While not prehensile, the tail helps the animal balance while climbing.[29]

The forepaws possess a "false thumb", which is an extension of a wrist bone, the radial

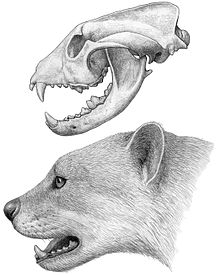

The red panda's skull is wide, and its lower jaw is robust.

Both sexes have paired anal glands that emit a secretion consisting of long-chain fatty acids, cholesterol, squalene and 2-Piperidinone; the latter is the most odoriferous compound and is perceived by humans as having an ammoniacal or pepper-like odour.[33]

Distribution and habitat

The red panda inhabits Nepal, the states of Sikkim, West Bengal and Arunachal Pradesh in India, Bhutan, southern Tibet, northern Myanmar and China's Sichuan and Yunnan provinces.[1] The global potential habitat of the red panda has been estimated to comprise 47,100 km2 (18,200 sq mi) at most; this habitat is located in the temperate climate zone of the Himalayas with a mean annual temperature range of 18–24 °C (64–75 °F).[34] Throughout this range, it has been recorded at elevations of 2,000–4,300 m (6,600–14,100 ft).[35][36][37][38][39]

| Country | Estimated size[34] |

|---|---|

| Nepal | 22,400 km2 (8,600 sq mi) |

| China | 13,100 km2 (5,100 sq mi) |

| India | 5,700 km2 (2,200 sq mi) |

| Myanmar | 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) |

| Bhutan | 900 km2 (350 sq mi) |

| Total | 47,100 km2 (18,200 sq mi) |

In Nepal, it lives in six protected area complexes within the

The red panda prefers

Behaviour and ecology

The red panda is difficult to observe in the wild,

Social spacing

Adult pandas are generally

Diet and feeding

The red panda is largely herbivorous and feeds primarily on bamboo, mainly the genera

The diet of red pandas monitored at three sites in

The red panda grabs food with one of its front paws and usually eats sitting down or standing. When foraging for bamboo, it grabs the plant by the stem and pulls it down towards its jaws. It bites the leaves with the side of the

Communication

At least seven different vocalisations have been recorded from the red panda, comprising growls, barks, squeals, hoots, bleats, grunts and twitters. Growling, barking, grunting and squealing are produced during fights and aggressive chasing. Hooting is made in response to being approached by another individual. Bleating is associated with scent-marking and sniffing. Males may bleat during mating, while females twitter.[71] During both play fighting and aggressive fighting, individuals curve their backs and tails while slowly moving their heads up and down. They then turn their heads while jaw-clapping, move their heads laterally and lift a forepaw to strike. They stand on their hind legs, raise the forelimbs above the head and then pounce. Two red pandas may "stare" at each other from a distance.[29]

Reproduction and parenting

Red pandas are

As the reproductive season begins, males and females interact more, and will rest, move, and feed near each other. An oestrous female will spend more time marking and males will inspect her anogenital region. Receptive females make tail-flicks and position themselves in a lordosis pose, with the front lowered to the ground and the spine curved. Copulation involves the male mounting the female from behind and on top, though face-to-face matings as well as belly-to-back matings while lying on the sides also occur. The male will grab the female by the sides with his front paws instead of biting her neck. Intromission is 2–25 minutes long, and the couple groom each other between each bout.[72]

Gestation lasts about 131 days.[73] Prior to giving birth, the female selects a denning site, such as a tree, log or stump hollow or rock crevice, and builds a nest using material from nearby, such as twigs, sticks, branches, bark bits, leaves, grass and moss.[57] Litters typically consist of one to four cubs that are born fully furred but blind. They are entirely dependent on their mother for the first three to four months until they first leave the nest. They nurse for their first five months.[73] The bond between mother and offspring lasts until the next mating season. Cubs are fully grown at around 12 months and at around 18 months they reach sexual maturity.[29] Two radio-collared cubs in eastern Nepal separated from their mothers at the age of 7–8 months and left their birth areas three weeks later. They reached new home ranges within 26–42 days and became residents after exploring them for 42–44 days.[41]

Mortality and diseases

The red panda's lifespan in captivity reaches 14 years.

Threats

The red panda is primarily threatened by the destruction and fragmentation of its habitat, the causes of which include increasing human population, deforestation, the unlawful taking of non-wood forest material and disturbances by herders and livestock.[1] Trampling by livestock inhibits bamboo growth,[74] and clearcutting decreases the ability of some bamboo species to regenerate.[83] The cut lumber stock in Sichuan alone reached 2,661,000 m3 (94,000,000 cu ft) in 1958–1960, and around 3,597.9 km2 (1,389.2 sq mi) of red panda habitat were logged between the mid-1970s and late 1990s.[48] Throughout Nepal, the red panda habitat outside protected areas is negatively affected by solid waste, livestock trails and herding stations, and people collecting firewood and medicinal plants.[43][84] Threats identified in Nepal's Lamjung District include grazing by livestock during seasonal transhumance, human-made forest fires and the collection of bamboo as cattle fodder in winter.[85] Vehicular traffic is a significant barrier to red panda movement between habitat patches.[60]

Poaching is also a major threat.[1] In Nepal, 121 red panda skins were confiscated between 2008 and 2018. Traps meant for other wildlife have been recorded killing red pandas.[86] In Myanmar, the red panda is threatened by hunting using guns and traps; since roads to the border with China were built starting in the early 2000s, red panda skins and live animals have been traded and smuggled across the border.[39] In southwestern China, the red panda is hunted for its fur, especially for the highly valued bushy tails, from which hats are produced. The red panda population in China has been reported to have decreased by 40 per cent over the last 50 years, and the population in western Himalayan areas are considered to be smaller.[48] Between 2005 and 2017, 35 live and seven dead red pandas were confiscated in Sichuan, and several traders were sentenced to 3–12 years of imprisonment. A month-long survey of 65 shops in nine Chinese counties in the spring of 2017 revealed only one in Yunnan offered hats made of red panda skins, and red panda tails were offered in an online forum.[87]

Conservation

The red panda is listed in

A red panda anti-poaching unit and community-based monitoring have been established in Langtang National Park. Members of Community Forest User Groups also protect and monitor red panda habitats in other parts of Nepal.[91] Community outreach programs have been initiated in eastern Nepal using information boards, radio broadcasting and the annual International Red Panda Day in September; several schools endorsed a red panda conservation manual as part of their curricula.[92]

Since 2010, community-based conservation programmes have been initiated in 10 districts in Nepal that aim to help villagers reduce their dependence on natural resources through improved herding and food processing practices and alternative income possibilities. The Nepali government ratified a five-year Red Panda Conservation Action Plan in 2019.[93] From 2016 to 2019, 35 ha (86 acres) of high-elevation rangeland in Merak, Bhutan, was restored and fenced in cooperation with 120 herder families to protect the red panda forest habitat and improve communal land.[94] Villagers in Arunachal Pradesh established two community conservation areas to protect the red panda habitat from disturbance and exploitation of forest resources.[46] China has initiated several projects to protect its environment and wildlife, including Grain for Green, The Natural Forest Protection Project and the National Wildlife/Natural Reserve Construction Project. For the last project, the red panda is not listed as a key species for protection but may benefit from the protection of the giant panda and golden snub-nosed monkey, with which it overlaps in range.[95]

In captivity

The

In 1978, a

Cultural significance

The red panda's role in the culture and folklore of local people is limited. A drawing of a red panda exists on a 13th-century Chinese scroll.

The red panda was recognised as the

References

- ^ a b c d e f Glatston, A.; Wei, F.; Than Zaw & Sherpa, A. (2017) [errata version of 2015 assessment]. "Ailurus fulgens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T714A110023718. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ Turner, R. L. (1931). "पञ्जा pañjā". A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 359. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "αἴλουρος". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Lewis, C. T. A. & Short, C. (1879). "fulgens". Latin Dictionary (Revised, enlarged, and in great part rewritten ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- S2CID 244938631.

- ^ Cuvier, F. (1825). "Panda". In Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, E.; Cuvier, F. (eds.). Histoire naturelle des mammifères, avec des figures originales, coloriées, dessinées d'après des animaux vivans: publié sous l'autorité de l'administration du Muséum d'Histoire naturelle (in French). Vol. 5. Paris: A. Belin. p. LII 1–3.

- ^ Cuvier, G. (1829). "Le Panda éclatant". Le règne animal distribué d'après son organisation (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Chez Déterville. p. 138.

- ^ Hardwicke, T. (1827). "Description of a new genus of the class Mammalia, from the Himalaya chain of hills between Nepal and the Snowy Mountains". The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. XV: 161–165.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- PMID 32133395.

- S2CID 231811193.

- PMID 33420314.

- PMID 8568209.

- ^ PMID 16012099.

- ^ PMID 28472434.

- ^ PMID 33591975.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ PMID 16387860.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ S2CID 4432191.

- S2CID 4214900.

- S2CID 82000411.

- PMID 11371595.

- PMID 28096377.

- PMID 29168616.

- ^ S2CID 243824295.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-0691154275.

- S2CID 13035672.

- PMID 17118063.

- .

- ^ .

- ^ a b Mallick, J. K. (2010). "Status of Red Panda Ailurus fulgens in Neora Valley National Park, Darjeeling District, West Bengal, India". Small Carnivore Conservation. 43: 30–36. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ S2CID 84332758.

- ^ PMID 33306732.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 9780128237540. Archivedfrom the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- .

- ^ PMID 34906253.

- ^ PMID 32963325.

- ^ a b c Panthi, S.; Aryal, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Lord, J. & Adhikari, B. (2012). "Summer diet and distribution of the Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens fulgens) in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Nepal" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 51 (5): 701–709. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Khatiwara, S. & Srivastava, T. (2014). "Red Panda Ailurus fulgens and other small carnivores in Kyongnosla Alpine Sanctuary, East Sikkim, India". Small Carnivore Conservation. 50: 35–38. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- .

- ^ S2CID 87668179.

- .

- ^ .

- .

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 22039497.

- ^ from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ PMID 32953073.

- ^ S2CID 86350625.

- ^ a b Zhou, X.; Jiao, H.; Dou, Y.; Aryal, A.; Hu, J.; Hu, J. & Meng, X. (2013). "The winter habitat selection of Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens) in the Meigu Dafengding National Nature Reserve, China" (PDF). Current Science. 105 (10): 1425–1429. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- S2CID 232763016.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 34720409.

- ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- .

- S2CID 85588401.

- .

- from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- .

- ^ .

- PMID 28306740.

- PMID 24498390.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-823753-3.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- .

- PMID 28894643.

- S2CID 238250774.

- PMID 10749446.

- PMID 31342874.

- PMID 29433401.

- PMID 30891398.

- PMID 33109179.

- ^ ISBN 2-8317-0046-9. Archived(PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- S2CID 92988737.

- .

- ^ S2CID 213958948.

- ^ Xu, L. & Guan, J. (2018). Red Panda market research findings in China (PDF). Cambridge: Traffic. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Datta, A.; Naniwadekar, R. & Anand, M. O. (2008). "Occurrence and conservation status of small carnivores in two protected areas in Arunachal Pradesh, north-east India". Small Carnivore Conservation. 39: 1–10. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ Bista, D. (2018). "Communities in frontline in Red Panda conservation, eastern Nepal" (PDF). The Himalayan Naturalist. 1 (1): 11–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- .

- S2CID 243813871.

- S2CID 243805749.

- .

- PMID 29512188.

- PMID 27795893.

- .

- ^ S2CID 243805192.

Notes

External links

- Red Panda Network – a non-profit organization committed to the conservation of wild red pandas