Resistance during World War II

| Timelines of World War II |

|---|

| Chronological |

| Prelude |

| By topic |

| By theatre |

| Part of a series on |

| Anti-fascism |

|---|

|

During World War II, resistance movements operated in German-occupied Europe by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation to propaganda, hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. In many countries, resistance movements were sometimes also referred to as The Underground.

The resistance movements in World War II can be broken down into two primary politically polarized camps:

- the anti-fascistresistance that existed in nearly every country in the world; and

- the various nationalist groups in German- or Soviet-occupied countries, such as the Republic of Poland, that opposed both Nazi Germanyand the Communists.

While historians and governments of some European countries have attempted to portray resistance to Nazi occupation as widespread among their populations,[1] only a small minority of people participated in organized resistance, estimated at one to three percent of the population of countries in western Europe. In eastern Europe where Nazi rule was more oppressive, a larger percentage of people were in organized resistance movements, for example, an estimated 10-15 percent of the Polish population. Passive resistance by non-cooperation with the occupiers was much more common.[2]

Summary of resistance movements by territory

Among the most notable resistance movements were:

Europe

- the Albanian resistance

- the Belgian Resistance

- the Czech resistance

- the Danish Resistance

- the Dutch Resistance (especially the "LO" (national hiding organisation))

- the French Resistance

- the Greek Resistance

- the Italian CLN)

- the Jewish Resistance in various German-occupied territories

- the Norwegian Resistance

- the Polish Home Army, that started the Warsaw Uprising on August 1, 1944, Leśni, and the greater Polish Underground State);

- Soviet partisans[a]

- Yugoslav Partisans

And the politically persecuted opposition in Germany itself (there were 16 main resistance groups and at least 27 failed attempts to assassinate Hitler with many more planned).

Far East

- the Chinese resistance

- the Korean Resistance in the Japan Occupied Korea and the Chinese Zone

Many countries had resistance movements dedicated to fighting or undermining the

Organization

After the first shock following the

There were many different types of groups, ranging in activity from humanitarian aid to armed resistance, and sometimes cooperated in varying degrees. Resistance usually arose spontaneously, but was encouraged and helped from London and Moscow.

Size

The six largest resistance movements in Europe were the Dutch, the French, the Italian (from 1943), the Polish, the Soviet, and the Yugoslav; overall their size can be seen as comparable, particularly in the years 1941–1944. Based on the percentage of the population actively fighting nazis, Yugoslavia was among top three countries in the EU, consisting of 400.000 fighters which was 2% of the population.

A number of sources note that the Polish Home Army was the largest resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Europe. Norman Davies writes that the "Armia Krajowa (Home Army), the AK,... could fairly claim to be the largest of European resistance [organizations]."[5] Gregor Dallas writes that the "Home Army (Armia Krajowa or AK) in late 1943 numbered around 400,000, making it the largest resistance organization in Europe."[6] Mark Wyman writes that the "Armia Krajowa was considered the largest underground resistance unit in wartime Europe."[7] However, the numbers of Soviet partisans were very similar to those of the Polish resistance,[8] as were the numbers of Yugoslav Partisans.[citation needed] For the French Resistance, François Marcot ventured an estimate of 200,000 activists and a further 300,000 with substantial involvement in Resistance operations.[9] For the Resistance in Italy, Giovanni di Capua estimates that, by August 1944, the number of partisans reached around 100,000, and it escalated to more than 250,000 with the final insurrection in April 1945.[10]

Forms of resistance

Various forms of resistance were:

- Non-violent

- Sabotage – the Arbeitseinsatz ("Work Contribution") forced locals to work for the Germans, but work was often done slowly or intentionally badly

- demonstrations

- Based on existing organizations, such as the churches, students, communists and doctors (professional resistance)

- Armed

- raids on distribution offices to get food coupons or various documents such as Ausweise or on birth registry offices to get rid of information about Jews and others to whom the Nazis paid special attention

- temporary liberation of areas, such as in Yugoslavia, Paris, and northern Italy, occasionally in cooperation with the Allied forces

- uprisings such as in Auschwitzin 1944

- continuing battle and

- Espionage, including sending reports of military importance (e.g. troop movements, weather reports etc.)

- Illegal press to counter Nazi propaganda

- Anti-Nazi propaganda including movies for example anti-Nazi color film Calling Mr. Smith (1943) about current Nazi crimes in German-occupied Poland.

- Covert listening to BBC broadcasts for news bulletins and coded messages

- Political resistance to prepare for the reorganization after the war

- Helping people to go into hiding (e.g., to escape the Arbeitseinsatz or deportation)—this was one of the main activities in the Netherlands, due to the large number of Jews and the high level of administration, which made it easy for the Germans to identify Jews.

- Escape and evasion lines to help Allied military personnel caught behind Axis lines

- Helping POWswith illegal supplies, breakouts, communication, etc.

- Forgery of documents

Resistance operations

1939–1940

On 15 September 1939, a member of the Czech resistance movement, Ctibor Novák, planted explosive devices in Berlin. His first bomb detonated in front of the Ministry of Aeronautics, and the second detonated in front of police headquarters. Both buildings were damaged and many Germans were injured.

On 28 October 1939 (the anniversary of the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918) there were large demonstrations against Nazi occupation in Prague, with about 100,000 Czechs. Demonstrators crowded the streets in the city. German police had to disperse the demonstrators, and began shooting in the evening. The first victim was baker Václav Sedláček, who was shot dead. The second victim was student Jan Opletal, who was critically injured, and died on 11 November. Another 15 people were badly injured and hundreds of people sustained minor injuries. About 400 people were arrested.

In March 1940, a

In 1940,

On the night of January 21–22, 1940, in the Soviet-occupied

1940 was the year of establishing the

One of the events that helped the growth of the French Resistance was the targeting of the French Jews, Communists, Romani, homosexuals, Catholics, and others, forcing many into hiding. This in turn gave the French Resistance new people to incorporate into their political structures.

Around May 1940, a resistance group formed around the Austrian priest Heinrich Maier, who until 1944 very successfully passed on the plans and production locations for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and airplanes (Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, etc.) to the Allies, so that they could target these important factories for destruction and on the other hand, for the after the war Central European states planned.[clarification needed] Very early on they passed on information about the mass murder of the Jews to the Allies.[17][18][19]

The

The organisation was officially dissolved on 15 January 1946.

1941

In February 1941, the Dutch Communist Party organized a general strike in Amsterdam and surrounding cities, known as the February strike, in protest against anti-Jewish measures by the Nazi occupying force and violence by fascist street fighters against Jews. Several hundreds of thousands of people participated in the strike. The strike was put down by the Nazis and some participants were executed.

In April 1941, the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation was established in the Province of Ljubljana. Its armed wing were the Slovene Partisans. It represented both the working class and the Slovene ethnicity.[21]

From April 1941,

Beginning in March 1941, Witold Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the

In May 1941, the Resistance Team "Elevtheria" (Freedom) was established in Thessaloniki by politicians Paraskevas Barbas, Apostolos Tzanis, Ioannis Passalidis, Simos Kerasidis, Athanasios Fidas, Ioannis Evthimiadis and military officer Dimitrios Psarros. Its armed wing comprised two armed forces; Athanasios Diakos led by Christodoulos Moschos (captain "Petros"), operating in Kroussia; and Odysseas Androutsos led by Athanasios Genios (captain "Lassanis"), operating in Visaltia.[24][25][26]

The first anti-soviet uprising during World War II began on June 22, 1941 (the start-date of Operation Barbarossa) in Lithuania. On the same day, the Sisak People's Liberation Partisan Detachment was formed in Croatia, near the town of Sisak. It was the first armed partisan unit in Croatia.

Communist-initiated

In July 1941

On 13 July 1941, in Italian-occupied Montenegro, Montenegrin separatist Sekula Drljević proclaimed an independent Kingdom of Montenegro as an Italian governorate, upon which a nationwide rebellion escalated raised by Partisans, Yugoslav Royal officers and various other armed personnel. It was the first organized armed uprising in then occupied Europe, and involved 32,000 people. Most of Montenegro was quickly liberated, except major cities where Italian forces were well fortified. On 12 August — after a major Italian offensive involving 5 divisions and 30,000 soldiers — the uprising collapsed as units were disintegrating; poor leadership occurred as well as collaboration. The final toll of July 13 uprising in Montenegro was 735 dead, 1120 wounded and 2070 captured Italians and 72 dead and 53 wounded Montenegrins.[citation needed]

In the

On 11 October 1941, in Bulgarian-occupied Prilep, Macedonians attacked post of the Bulgarian occupation police, which was the start of Macedonian resistance against the fascists who occupied Macedonia: Germans, Italians, Bulgarians and Albanians. The resistance finished successfully in August–November 1944 when the independent Macedonian state was formed, which was later added to the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.

At the time Hitler gave his anti-resistance .

1942

On February 16, 1942, the Greek Communist Party (

The Luxembourgish general strike of 1942 was a passive resistance movement organised within a short time period to protest against a directive that incorporated the Luxembourg youth into the Wehrmacht. A national general strike, originating mainly in Wiltz, paralysed the country and forced the occupying German authorities to respond violently by sentencing 21 strikers to death.

On 27 May 1942

In September 1942, the Council to Aid Jews (

On the night of 7–8 October 1942,

On 25 November, Greek guerrillas with the help of twelve British saboteurs

On 20 June 1942, the most spectacular escape from

The

1943

By the middle of 1943 partisan resistance to the Germans and their allies had grown from the dimensions of a mere nuisance to those of a major factor in the general situation. In many parts of occupied Europe Germany was suffering losses at the hands of partisans that he could ill afford. Nowhere were these losses heavier than in Yugoslavia.[38]

In early January 1943, the 20,000 strong main operational group of the

On 19 April 1943, three members of the

One of the bravest and most significant displays of public defiance against the Nazis is the rescue of the Danish Jews in October 1943. Nearly all of the Danish Jews were saved from concentration camps by the Danish resistance. However, the action was largely due to the personal intervention of German diplomat Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who both leaked news of the intended round up of the Jews to both the Danish opposition and Jewish groups and negotiated with the Swedes to ensure Danish Jews would be accepted in Sweden.

The

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising by the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto lasted from 19 April-16 May, and cost the Nazi forces 17 dead and 93 wounded by their own count, though some Jewish resistance figures claimed that German casualties were far higher.

On 30 September the

On October 9, 1943, the Kinabalu guerillas launched the

From November 1943,

1944

On 1 February 1944, the Resistance fighters of the Polish

In the spring of 1944, a plan was laid out by the Allies to kidnap General Müller, whose harsh repressive measures had earned him the nickname "the Butcher of Crete". The operation was led by Major Patrick Leigh Fermor, together with Captain W. Stanley Moss, Greek SOE agents and Cretan resistance fighters. However, Müller left the island before the plan could be carried out. Undeterred, Fermor decided to abduct General Heinrich Kreipe instead.

On the night of 26 April, General Kreipe left his headquarters in Archanes and headed without escort to his well-guarded residence, "Villa Ariadni", approximately 25 km outside Heraklion. Major Fermor and Captain Moss, dressed as German military policemen, waited for him 1 km (0.62 mi) before his residence. They asked the driver to stop and asked for their papers. As soon as the car stopped, Fermor quickly opened Kreipe's door, rushed in and threatened him with his guns while Moss took the driver's seat. After driving some distance the British left the car, with suitable decoy material being planted that suggesting an escape off the island had been made by submarine, and with the General began a cross-country march. Hunted by German patrols, the group moved across the mountains to reach the southern side of the island, where a British Motor Launch (ML 842, commanded by Brian Coleman) was to pick them up. Eventually, on 14 May 1944, they were picked up (from Peristeres beach near Rhodakino) and transferred to Egypt.

In April–May 1944, the

An intricate series of resistance operations were launched in France prior to, and during, Operation Overlord. On June 5, 1944, the

On 25 June 1944, the

Norwegian

As an initiation of their uprising, Slovakian rebels entered Banská Bystrica on the morning of 30 August 1944, the second day of the rebellion, and made it their headquarters. By 10 September, the insurgents gained control of large areas of central and eastern Slovakia. That included two captured airfields. As a result of the two-week-old insurgency, the Soviet Air Force was able to begin flying in equipment to Slovakian and Soviet partisans.

Resistance movements during World War II

- Albanian resistance movement

- National Liberation Movement

- Balli Kombëtar (anti-Italian and later anti-communist and anti-Yugoslav resistance movements)

- Legality Movement

- Austrian resistance movement (e.g. O5)

- Belgian Resistance

- Armée Belge Reconstituée(ABR)

- Armée secrète(AS)

- Comet Line

- Comité de Défense des Juifs(CDJ, Jewish resistance)

- Front de l'Indépendance (FI)

- Groupe G

- Kempische Legioen(KL)

- Légion Belge

- Milices Patriotiques (MP-PM)

- Mouvement National Belge (MNB)

- Mouvement National Royaliste(MNR-NKB)

- Organisation Militaire Belge de Résistance (OMBR)

- Partisans Armés (PA)

- Service D

- Witte Brigade

- Borneo resistance movement

- British resistance movements[4][54]

- SIS Section D and Section VII (planned Resistance organisations)

- Auxiliary Units (planned hidden commando force to operate during military anti-invasion campaign)

- Resistance to German occupation of the Channel Islands

- Bulgarian resistance movements

- Bulgarian resistance movement

- Goryani (anti-communist resistance from 1944)

- Burman resistance movements:

- Burma Independence Army (anti-British)

- Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League

- Forest Brothers")

- Chechen resistance movement (anti-Soviet)

- Chinese resistance movements

- Anti-Japanese Army For The Salvation Of The Country

- Chinese People's National Salvation Army

- Heilungkiang National Salvation Army

- Jilin Self-Defence Army

- Northeast Anti-Japanese National Salvation Army

- Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army

- Northeast People's Anti-Japanese Volunteer Army

- Northeastern Loyal and Brave Army

- Northeastern People's Revolutionary Army

- Northeastern Volunteer Righteous & Brave Fighters

- Hong Kong resistance movements

- Gangjiu dadui (Hong Kong-Kowloon brigade)

- East River Column (Dongjiang Guerrillas, Southern China and Hong Kong organisation)

- Islamic resistance movement against Japan

- Muslim Detachment (回民義勇隊 Huimin Zhidui)

- Muslim corps

- Czech resistance movement

- Danish resistance movement

- Dutch resistance movement

- The Stijkel Group, a Dutch resistance movement, which mainly operated around the S-Gravenhage area.

- Valkenburg resistance

- Estonian resistance movement

- Ethiopian resistance movement

- Pro-German resistance movement in Finland

- French resistance movement

- Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action (BCRA)

- Conseil National de la Résistance(CNR)

- Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP)

- Free French Forces(FFL)

- French Forces of the Interior (FFI)

- Maquis

- Pat O'Leary Line

- German anti-Nazi resistance movements

- Bästlein-Jacob-Abshagen Group

- Black Orchestra

- Confessing Church

- Edelweiss Pirates

- Ehrenfeld Group

- European Union

- Kreisau Circle

- National Committee for a Free Germany

- Neu Beginnen

- Red Orchestra

- Robert Uhrig Group

- Saefkow-Jacob-Bästlein Organization

- Solf Circle

- Vierergruppen in Hamburg, Munich and Vienna

- White Rose

- German pro-Nazi resistance in Allied-occupied areas

- Volkssturm – a German resistance group and militia created by the NSDAP near the end of World War II

- Werwolf – Nazi German resistance movement against the Allied occupation

- Greek Resistance

- List of Greek Resistance organizations

- Cretan resistance

- Greek People's Liberation Army(ELAS), EAM's guerrilla forces

- National Republican Greek League(EDES)

- National and Social Liberation (EKKA)

- Indian resistance movements:

- Quit India Movement

- Azad Hind

- Britain) in Southeast Asia and along India's easternmost borderlands

- Indonesian resistance movements

- Italian resistance movement

- Arditi del Popolo

- Assisi Network

- Brigate Fiamme Verdi

- Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale

- Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana

- DELASEM

- Democrazia Cristiana

- Four days of Naples

- Giustizia e Libertà

- Italian Civil War

- Air Force

- Italian Communist Party (PCI)

- Italian partisan republics

- Italian Socialist Party (PSI)

- Labour Democratic Party (PDL)

- Movimento Comunista d'Italia

- National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy

- Partito d'Azione

- Scintilla

- Italian resistance against the Allies

- Japanese anti-imperial resistance

- Japanese pro-imperial resistance

- Jewish resistance in German-occupied Europe (transnational)

- Korean resistance movement

- Latvian resistance movement

- Libyan resistance movement

- Lithuanian resistance during World War II

- Lithuanian Activist Front

- Lithuanian Freedom Army

- Luxembourgish resistance during World War II

- Malayan resistance movemment

- Moldovan resistance during World War II

- Norwegian resistance movement

- Milorg

- Nortraship

- Norwegian Independent Company 1 (Kompani Linge)

- Osvald Group

- XU

- Philippine resistance movement

- Filipino civilians).[55]

- Moro Muslim resistance movement

- Hukbalahap

- Polish resistance movement

- Armia Krajowa(Home Army—mainstream: Authoritarian/Western Democracy)

- Armia Ludowa(People's Army [Soviet proxy])

- Bataliony Chłopskie(Farmers' Battalions—mainstream, apolitical, stress on private property)

- Cursed soldiers (anti-communist)

- Gwardia Ludowa(People's Guard [Soviet proxy])

- Gwardia Ludowa WRN(The People's Guard Freedom Equality Independence—mainstream Polish Socialist Party's underground, progressive, anti—Nazi and anti—Soviet)

- Leśni (various "forest People")

- Narodowe Siły Zbrojne(National Armed Forces – Anti-Nazi, Anti-Communist)

- Polish Secret State

- Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB, Jewish Fighting Organisation in Poland)

- Żydowski Związek Walki(ŻZW, Jewish Fighting Union in Poland)

- Russian pro-Nazi German collaborationist movement

- Anti-Soviet partisans

- Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (Russian pro-Nazi German collaborationist resistance movement)

- GULAG Operation

- Lokot Autonomy

- Russian Fascist Party

- Russian Liberation Movement

- Union for the Struggle for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia

- White movement members within pro-Nazi circles

- Singaporean resistance movement

- Slovak resistance movement

- Soviet resistance movement

- Thai resistance movement

- Tigrayan resistance movement (anti-Ethiopian)

- Ukrainian resistance movements:

- Ukrainian Insurgent Army (anti-German, anti-Soviet and anti-Polish resistance movement)

- Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army (anti-German, anti-Soviet and anti-Polish resistance movement)

- Ustaše – Croatian nationalist and fascist resistance movement against the Kingdom of Yugoslavia/Chetniks and Yugoslav communists

- Viet Minh (Vietnamese resistance organization that fought Vichy France and the Japanese, and later against the French attempt to re-occupy Vietnam)

- Yugoslav resistance movement

- Axis, and anti-Yugoslav royalist anti-Chetniksresistance movement)

- Croatian Partisans

- Macedonian Partisans

- Serbian Partisans

- Slovene Partisans

-

- Blue Guard – Slovenian Chetniks

- TIGR (Slovene and Croat anti-Italian resistance movement, active between 1927 and 1941. Gradually absorbed into the Yugoslav Partisans throughout WWII.)[57][58]

Notable individuals

- Josip Broz Tito

- Charles De Gaulle

- Koča Popović

- Sava Kovačević

- Giorgio Amendola

- Tuvia Bielski

- Mordechaj Anielewicz

- Dawid Apfelbaum

- Yitzhak Arad

- Walter Audisio

- Georges Bidault

- Alexander Bogen

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer

- Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski

- Petr Braiko

- Pierre Brossolette

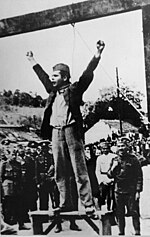

- Masha Bruskina

- Taras Bulba-Borovets

- Alexander Chekalin

- Danielle Casanova

- Marek Edelman

- Henri Honoré d'Estienne d'Orves

- D'Arcy Osborne, 12th Duke of Leeds

- Paul Eluard

- Oleksiy Fedorov

- Manolis Glezos

- Marianne Golz

- Stefan Grot-Rowecki

- Jens Christian Hauge

- Aris Velouchiotis

- Enver Hoxha

- Khasan Israilov

- Jan Karski

- Stanisław Aronson

- Vassili Kononov

- Oleg Koshevoy

- Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya

- Sydir Kovpak

- Nikolai Kuznetsov

- Albert Kwok

- Hans Litten

- Abbé Pierre

- Martin Linge

- Luigi Longo

- Zivia Lubetkin

- Juozas Lukša

- Pavel Luspekayev

- Max Manus

- Pyotr Masherov

- Ho Chi Minh

- Kim Ku

- Lee Bong-chang

- Yun Bong-gil

- Mustapha bin Harun

- Ma Benzhai (zh:馬本齋)

- Missak Manouchian

- Jean Moulin

- Omar Mukhtar

- Otomars Oškalns

- Ferruccio Parri

- Alexander Pechersky

- Motiejus Pečiulionis (lt)

- Salipada Pendatun

- Chin Peng

- Sandro Pertini

- Gumbay Piang

- Witold Pilecki

- Christian Pineau

- Panteleimon Ponomarenko

- Zinaida Portnova

- Lepa Radić

- Adolfas Ramanauskas

- Semyon Rudniev

- Alexander Saburov

- Hannie Schaft

- Pierre Schunck

- Sophie Scholl

- Baron Jean de Selys Longchamps

- Roman Shukhevych

- Henk Sneevliet

- Arturs Sproģis

- Ilya Starinov

- Claus von Stauffenberg

- Imants Sudmalis

- Ramon Magsaysay

- Gunnar Sønsteby

- Luis Taruc

- Palmiro Togliatti

- Aris Velouchiotis

- Pyotr Vershigora

- Nancy Wake

- Napoleon Zervas

- Henri Giraud

- Romain Gary

- Simcha Zorin

- Jonas Žemaitis

- Kaji Wataru

- Sanzo Nosaka

- Gijs van Hall

- Walraven van Hall

- Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema

- Velimir Đurić

- Yitzhak Zuckerman

- Mordecai Anielewicz

Documentaries

- Confusion was their business from the BBC series Secrets of World War II is a documentary about the SOE (Special Operations Executive) and its operations

- The Real Heroes of Telemark is a book and documentary by survival expert Ray Mears about the Norwegian sabotage of the German nuclear program (Norwegian heavy water sabotage)

- Making Choices: The Dutch Resistance during World War II (2005) This award-winning, hour-long documentary tells the stories of four participants in the Dutch Resistance and the miracles that saved them from certain death at the hands of the Nazis.

Dramatisations

- situation comedyabout the French resistance movement (a parody of Secret Army)

- L’Armée des ombres (1969) internal and external battles of the French resistance. Directed by Jean-Pierre Melville

- Fourth anti-Partisan Offensive(Fall Weiss), also known as The Battle for the Wounded

- Black Book (film) (2006) depicts double and triple crosses amongst the Dutch Resistance

- Bonhoeffer (2004 premier at the Acacia Theatre) is a play about Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a pastor in the Confessing Churchexecuted for his participation in the German resistance.

- Boško Buha (1978) tells the tale of a boy who conned his way into partisan ranks aged 15 and became legendary for his talent of destroying enemy bunkers

- Charlotte Gray (2001) – thought to be based on Nancy Wake

- Twentieth Century Fox.

- Come and See (1985) is a Soviet made film about partisans in Belarus, as well as war crimes committed by the war's various factions.

- Belorussia.

- Flame & Citron (2008) is a movie based on two Danish resistance fighters who were in the Holger Danske (resistance group).

- The Four Days of Naples (1962) is a movie based on the popular uprising against the German forces occupying the Italian city of Naples.

- GL

- The Heroes of Telemark (1965) is very loosely based on the Norwegian sabotage of the German nuclear program (the later Real Heroes of Telemark is more accurate)

- Het meisje met het rode haar (1982) (Dutch) is about Dutch resistance fighter Hannie Schaft

- Kanał (1956) (Polish) first film ever to depict Warsaw Uprising

- The Longest Day (1962) features scenes of the resistance operations during Operation Overlord

- Massacre in Rome (1973) is based on a true story about Nazi retaliation after a resistance attack in Rome

- My Opposition: the Diaries of Friedrich Kellner (2007) is a Canadian film about Justice Inspector Friedrich Kellner of Laubachwho challenged the Nazis before and during the war

- Resistance (2003): a film based on a 1995 book of the same title by Anita Shreve. The plot revolves around a downed American pilot who is sheltered by the Belgian resistance.

- Secret Army(1977) a television series about the Belgian resistance movement, based on real events

- Sea Of Blood (1971) a North Korean opera depicting Anti-Japanese resistance

- Soldaat van Oranje(1977) (Dutch) is about some Dutch students who enter the resistance in cooperation with England

- Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage (2005) is about the last days in the life of Sophie Scholl

- Stärker als die Nacht (1954) (East German) follows the story of a group of German Communist resistance fighters

- Fifth anti-Partisan Offensive(Fall Schwartz)

- Winter in Wartime (film), 2008 adaptation of Jan Terlouw's 1972 novel, about a Dutch youth whose favors for members of the Dutch Resistance during the last winter of World War II have a devastating impact on his family

- The Resistance Banker Bankier van het verzet (film), is a 2018 Dutch World-War-II-period drama film directed by Joram Lürsen. The film is based on the life of banker Walraven van Hall, who financed the Dutch resistance during the Second World War.

See also

- Anti-partisan operations in World War II

- Anti-Soviet partisans

Notes

a

Several sources note that Polish

After that point, the numbers of

The numbers of Tito's

The numbers of

References

- ^ Rosbottom, Ronald C. (2014), When Paris Went Dark, New York: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 198-199

- ^ Wieviorka, Olivier and Tebinka, Jacek, "Resisters: From Everyday Life to Counter-state," in Surviving Hitler and Mussolini (2006), eds: Robert Gildea, Olivier Wieviorka, and Anette Warring, Oxford: Berg, p. 153

- ISBN 978-1-47383-377-7.

- ^ a b "British Resistance Archive – Churchill's Auxiliary Units – A comprehensive online resource". www.coleshillhouse.com.

- ISBN 978-0-231-12819-3. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^

- ^ See, for example, Leonid D. Grenkevich, The Soviet Partisan Movement, 1941–44: A Critical Historiographical Analysis, p. 229, and Walter Laqueur, The Guerilla Reader: A Historical Anthology, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1990, p. 233.

- ISBN 978-2-221-09997-1.

- ^ Resistenzialismo versus resistenza

- ISBN 978-83-912237-0-3

- ISBN 978-0-7391-8535-3

- ISBN 978-0-8094-8925-1

- ]

- ISBN 978-83-912000-3-2

- ^ "Names of Righteous by Country". www.yadvashem.org. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ISBN 978-3-902494-83-2, p 299–305.

- ^ Peter Broucek "Die österreichische Identität im Widerstand 1938–1945" (2008), p 163.

- ^ Hansjakob Stehle "Die Spione aus dem Pfarrhaus (German: The spy from the rectory)" In: Die Zeit, 5 January 1996.

- ISBN 978-0-7146-5528-4.

- ISBN 961-213-129-5.

- ^ Halina Auderska, Zygmunt Ziółek, Akcja N. Wspomnienia 1939–1945 (Action N. Memoirs 1939–1945), Wydawnictwo Czytelnik, Warszawa, 1972 (in Polish)

- ^ Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Oxford University Presse, 1996, ISBN

- ^ newspaper Αυγή (Avgi), article: 68 years from the liberation of Thessaloniki from the nazis

- ^ newspaper Πρώτη Σελίδα (Proti Selida), article: 11th Reunion of Kilkisiotes, The Kilkisiotes of Athens honored the Holocaust of Kroussia Archived 2013-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ newspaper Ριζοσπάστης (Rizospastis), article: The murder of the members of the Macedonian Bureau of the Communist Party of Greece

- ^ Tessa Stirling et al., Intelligence Co-operation between Poland and Great Britain during World War II, vol. I: The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee, London, Vallentine Mitchell, 2005

- ^ Churchill, Winston Spencer (1951). The Second World War: Closing the Ring. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. p. 643.

- ^ Major General Rygor Slowikowski, "In the secret service – The lightning of the Torch", The Windrush Press, London 1988, s. 285

- ISBN 978-0-7864-0371-4.

- ^ Baczynska, Gabriela; JonBoyle (2008-05-12). "Sendler, savior of Warsaw Ghetto children, dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-05-12.[dead link]

- ^ Christopher M. Woodhouse, "The struggle for Greece, 1941–1949", Hart-Davis Mc-Gibbon, 1977, Google print, p.37

- ^ Richard Clogg, "A Short History of Modern Greece", Cambridge University Press, 1979 Google print, pp.142-143

- ^ Procopis Papastratis, "British policy towards Greece during the Second World War, 1941-1944", Cambridge University Press, 1984 Google print, p.129

- ^ Wojciech Zawadzki (2012), Eugeniusz Bendera (1906-po 1970). Przedborski Słownik Biograficzny, via Internet Archive.

- ISBN 83-7257-122-8

- ^ En.auschwitz.org Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Basil Davidson: PARTISAN PICTURE". www.znaci.net.

- ^ Operation WEISS – The Battle of Neretva

- ^ Battles & Campaigns during World War 2 in Yugoslavia

- ^ Barbagallo, Corrado, Napoli contro il terrore nazista. Maone, Naples.

- ^ Ordway, Frederick I., III. The Rocket Team. Apogee Books Space Series 36 (pp. 158, 173)

- ^ Piotr Stachniewicz, "Akcja" "Kutschera", Książka i Wiedza, Warszawa 1982,

- ISBN 978-3-86509-020-1

- ^ pp. 343-376, Eyre

- ISBN 9788682235408.

- ^ a b Leary (1995), p. 30

- ^ Ford (1992), p. 100

- ^ "US commemorates Serbian support during WWII". 21 November 2016.

- ^ Tomasevich (1975), p. 378

- ^ Leary (1995), p. 32

- ^ Kelly (1946), p. 62

- ISBN 978-1-47383-377-7.

- ^ "HyperWar: US Army in WWII: Triumph in the Philippines [Chapter 33]". www.ibiblio.org.

- ^ "Chetnik". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Milica Kacin Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi. Primorska 1925-1935 (Koper: Lipa, 1990)

- ^ Website of the TIGR Society

- ^ ]

- ^ a b Anna M. Cienciala, The coming of the War and Eastern Europe in World War II., History 557 Lecture Notes

- ^ Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland, Columbia University Press, 2005,

- ^ See for example: Leonid D. Grenkevich in The Soviet Partisan Movement, 1941-44: A Critical Historiographical Analysis, p.229 or Walter Laqueur in The Guerilla Reader: A Historical Anthology, (New York, Charles Scribiner, 1990, p.233.

- ISBN 978-0-275-99651-2. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-4022-0045-8. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

External links

- Jewish Armed Resistance and Rebellions on the Yad Vashem website

- Home of the British Resistance Movement

- European Resistance Archive

- Interviews from the Underground Eyewitness accounts of Russia's Jewish resistance during World War II; website & documentary film.

- Serials and Miscellaneous Publications of the Underground Movements in Europe During World War II, 1936-1945 From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Underground Movement Collection From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- "British Resistance in WW2". 2015.