Restriction enzyme

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or restrictase is an

These enzymes are found in bacteria and archaea and provide a defense mechanism against invading viruses.[4][5] Inside a prokaryote, the restriction enzymes selectively cut up foreign DNA in a process called restriction digestion; meanwhile, host DNA is protected by a modification enzyme (a methyltransferase) that modifies the prokaryotic DNA and blocks cleavage. Together, these two processes form the restriction modification system.[6]

More than 3,600 restriction endonucleases are known which represent over 250 different specificities.[7] Over 3,000 of these have been studied in detail, and more than 800 of these are available commercially.[8] These enzymes are routinely used for DNA modification in laboratories, and they are a vital tool in molecular cloning.[9][10][11]

History

The term restriction enzyme originated from the studies of phage λ, a virus that infects bacteria, and the phenomenon of host-controlled restriction and modification of such bacterial phage or bacteriophage.[12] The phenomenon was first identified in work done in the laboratories of Salvador Luria, Jean Weigle and Giuseppe Bertani in the early 1950s.[13][14] It was found that, for a bacteriophage λ that can grow well in one strain of Escherichia coli, for example E. coli C, when grown in another strain, for example E. coli K, its yields can drop significantly, by as much as 3-5 orders of magnitude. The host cell, in this example E. coli K, is known as the restricting host and appears to have the ability to reduce the biological activity of the phage λ. If a phage becomes established in one strain, the ability of that phage to grow also becomes restricted in other strains. In the 1960s, it was shown in work done in the laboratories of Werner Arber and Matthew Meselson that the restriction is caused by an enzymatic cleavage of the phage DNA, and the enzyme involved was therefore termed a restriction enzyme.[4][15][16][17]

The restriction enzymes studied by Arber and Meselson were type I restriction enzymes, which cleave DNA randomly away from the recognition site.

Origins

Restriction enzymes likely evolved from a common ancestor and became widespread via

Recognition site

Restriction enzymes recognize a specific sequence of nucleotides[2] and produce a double-stranded cut in the DNA. The recognition sequences can also be classified by the number of bases in its recognition site, usually between 4 and 8 bases, and the number of bases in the sequence will determine how often the site will appear by chance in any given genome, e.g., a 4-base pair sequence would theoretically occur once every 4^4 or 256bp, 6 bases, 4^6 or 4,096bp, and 8 bases would be 4^8 or 65,536bp.[28] Many of them are palindromic, meaning the base sequence reads the same backwards and forwards.[29] In theory, there are two types of palindromic sequences that can be possible in DNA. The mirror-like palindrome is similar to those found in ordinary text, in which a sequence reads the same forward and backward on a single strand of DNA, as in GTAATG. The inverted repeat palindrome is also a sequence that reads the same forward and backward, but the forward and backward sequences are found in complementary DNA strands (i.e., of double-stranded DNA), as in GTATAC (GTATAC being complementary to CATATG).[30] Inverted repeat palindromes are more common and have greater biological importance than mirror-like palindromes.

EcoRI digestion produces "sticky" ends,

whereas SmaI restriction enzyme cleavage produces "blunt" ends:

Recognition sequences in DNA differ for each restriction enzyme, producing differences in the length, sequence and strand orientation (

Different restriction enzymes that recognize the same sequence are known as neoschizomers. These often cleave in different locales of the sequence. Different enzymes that recognize and cleave in the same location are known as isoschizomers.

Types

Naturally occurring restriction endonucleases are categorized into five groups (Types I, II, III, IV, and V) based on their composition and

- Type I enzymes (EC 3.1.21.3) cleave at sites remote from a recognition site; require both ATP and S-adenosyl-L-methionine to function; multifunctional protein with both restriction digestion and methylase (EC 2.1.1.72) activities.

- Type II enzymes (EC 3.1.21.4) cleave within or at short specific distances from a recognition site; most require magnesium; single function (restriction digestion) enzymes independent of methylase.

- Type III enzymes (EC 3.1.21.5) cleave at sites a short distance from a recognition site; require ATP (but do not hydrolyse it); S-adenosyl-L-methionine stimulates the reaction but is not required; exist as part of a complex with a modification methylase (EC 2.1.1.72).

- Type IV enzymes target modified DNA, e.g. methylated, hydroxymethylated and glucosyl-hydroxymethylated DNA

- Type V enzymes utilize guide RNAs (gRNAs)

Type l

Type I restriction enzymes were the first to be identified and were first identified in two different strains (K-12 and B) of

Type II

| Type II site-specific deoxyribonuclease-like | |

|---|---|

Typical type II restriction enzymes differ from type I restriction enzymes in several ways. They form

Type IIB restriction enzymes (e.g., BcgI and BplI) are

Type III

Type III restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoP15) recognize two separate non-palindromic sequences that are inversely oriented. They cut DNA about 20–30 base pairs after the recognition site.

Type IV

Type IV enzymes recognize modified, typically methylated DNA and are exemplified by the McrBC and Mrr systems of E. coli.[35]

Type V

Type V restriction enzymes (e.g., the cas9-gRNA complex from CRISPRs[46]) utilize guide RNAs to target specific non-palindromic sequences found on invading organisms. They can cut DNA of variable length, provided that a suitable guide RNA is provided. The flexibility and ease of use of these enzymes make them promising for future genetic engineering applications.[46][47]

Artificial restriction enzymes

Artificial restriction enzymes can be generated by fusing a natural or engineered

In 2013, a new technology CRISPR-Cas9, based on a prokaryotic viral defense system, was engineered for editing the genome, and it was quickly adopted in laboratories.[57] For more detail, read CRISPR (Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats).

In 2017, a group from University of Illinois reported using an Argonaute protein taken from Pyrococcus furiosus (PfAgo) along with guide DNA to edit DNA in vitro as artificial restriction enzymes.[58]

Artificial ribonucleases that act as restriction enzymes for RNA have also been developed. A PNA-based system, called a PNAzyme, has a Cu(II)-2,9-dimethylphenanthroline group that mimics ribonucleases for specific RNA sequence and cleaves at a non-base-paired region (RNA bulge) of the targeted RNA formed when the enzyme binds the RNA. This enzyme shows selectivity by cleaving only at one site that either does not have a mismatch or is kinetically preferred out of two possible cleavage sites.[59]

Nomenclature

| Derivation of the EcoRI name | ||

|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation | Meaning | Description |

| E | Escherichia | genus |

| co | coli | specific species |

| R | RY13 | strain |

| I | First identified | order of identification in the bacterium |

Since their discovery in the 1970s, many restriction enzymes have been identified; for example, more than 3500 different Type II restriction enzymes have been characterized.[60] Each enzyme is named after the bacterium from which it was isolated, using a naming system based on bacterial genus, species and strain.[61][62] For example, the name of the EcoRI restriction enzyme was derived as shown in the box.

Applications

Isolated restriction enzymes are used to manipulate DNA for different scientific applications.

They are used to assist insertion of genes into

Restriction enzymes can also be used to distinguish gene

In a similar manner, restriction enzymes are used to digest

Artificial restriction enzymes created by linking the FokI DNA cleavage domain with an array of DNA binding proteins or zinc finger arrays, denoted zinc finger nucleases (ZFN), are a powerful tool for host genome editing due to their enhanced sequence specificity. ZFN work in pairs, their dimerization being mediated in-situ through the FokI domain. Each zinc finger array (ZFA) is capable of recognizing 9–12 base pairs, making for 18–24 for the pair. A 5–7 bp spacer between the cleavage sites further enhances the specificity of ZFN, making them a safe and more precise tool that can be applied in humans. A recent Phase I clinical trial of ZFN for the targeted abolition of the CCR5 co-receptor for HIV-1 has been undertaken.[69]

Others have proposed using the bacteria R-M system as a model for devising human anti-viral gene or genomic vaccines and therapies since the RM system serves an innate defense-role in bacteria by restricting tropism by bacteriophages.

Examples

Examples of restriction enzymes include:[76]

| Enzyme | Source | Recognition Sequence | Cut |

|---|---|---|---|

| EcoRI | Escherichia coli |

5'GAATTC 3'CTTAAG |

5'---G AATTC---3' 3'---CTTAA G---5' |

EcoRII |

Escherichia coli |

5'CCWGG 3'GGWCC |

5'--- CCWGG---3' 3'---GGWCC ---5' |

| BamHI | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens |

5'GGATCC 3'CCTAGG |

5'---G GATCC---3' 3'---CCTAG G---5' |

| HindIII | Haemophilus influenzae |

5'AAGCTT 3'TTCGAA |

5'---A AGCTT---3' 3'---TTCGA A---5' |

| TaqI | Thermus aquaticus |

5'TCGA 3'AGCT |

5'---T CGA---3' 3'---AGC T---5' |

| NotI | Nocardia otitidis |

5'GCGGCCGC 3'CGCCGGCG |

5'---GC GGCCGC---3' 3'---CGCCGG CG---5' |

| HinFI | Haemophilus influenzae |

5'GANTC 3'CTNAG |

5'---G ANTC---3' 3'---CTNA G---5' |

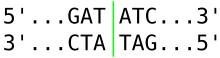

| Sau3AI | Staphylococcus aureus |

5'GATC 3'CTAG |

5'--- GATC---3' 3'---CTAG ---5' |

| PvuII* | Proteus vulgaris |

5'CAGCTG 3'GTCGAC |

5'---CAG CTG---3' 3'---GTC GAC---5' |

| SmaI* | Serratia marcescens |

5'CCCGGG 3'GGGCCC |

5'---CCC GGG---3' 3'---GGG CCC---5' |

| HaeIII* | Haemophilus aegyptius |

5'GGCC 3'CCGG |

5'---GG CC---3' 3'---CC GG---5' |

| HgaI[77] | Haemophilus gallinarum |

5'GACGC 3'CTGCG |

5'---NN NN---3' 3'---NN NN---5' |

| AluI* | Arthrobacter luteus |

5'AGCT 3'TCGA |

5'---AG CT---3' 3'---TC GA---5' |

| EcoRV* | Escherichia coli |

5'GATATC 3'CTATAG |

5'---GAT ATC---3' 3'---CTA TAG---5' |

| EcoP15I | Escherichia coli |

5'CAGCAGN25NN 3'GTCGTCN25NN |

5'---CAGCAGN25 NN---3' 3'---GTCGTCN25NN ---5' |

| KpnI[78] | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

5'GGTACC 3'CCATGG |

5'---GGTAC C---3' 3'---C CATGG---5' |

| PstI[78] | Providencia stuartii |

5'CTGCAG 3'GACGTC |

5'---CTGCA G---3' 3'---G ACGTC---5' |

| SacI[78] | Streptomyces achromogenes |

5'GAGCTC 3'CTCGAG |

5'---GAGCT C---3' 3'---C TCGAG---5' |

| SalI[78] | Streptomyces albus |

5'GTCGAC 3'CAGCTG |

5'---G TCGAC---3' 3'---CAGCT G---5' |

| ScaI*[78] | Streptomyces caespitosus |

5'AGTACT 3'TCATGA |

5'---AGT ACT---3' 3'---TCA TGA---5' |

| SpeI | Sphaerotilus natans |

5'ACTAGT 3'TGATCA |

5'---A CTAGT---3' 3'---TGATC A---5' |

| SphI[78] | Streptomyces phaeochromogenes |

5'GCATGC 3'CGTACG |

5'---GCATG C---3' 3'---C GTACG---5' |

| StuI*[79][80] | Streptomyces tubercidicus |

5'AGGCCT 3'TCCGGA |

5'---AGG CCT---3' 3'---TCC GGA---5' |

| XbaI[78] | Xanthomonas badrii

|

5'TCTAGA 3'AGATCT |

5'---T CTAGA---3' 3'---AGATC T---5' |

Key:

* = blunt ends

N = C or G or T or A

W = A or T

See also

- BglII – a restriction enzyme

- EcoRI – a restriction enzyme

- HindIII – a restriction enzyme

- Homing endonuclease

- List of homing endonuclease cutting sites

- List of restriction enzyme cutting sites

- Molecular-weight size marker

- REBASE (database)

- Star activity

References

- PMID 795607.

- ^ PMID 2172084.

- ISBN 0-89603-234-5.

- ^ PMID 4897066.

- PMID 6314109.

- PMID 11557807.

- PMID 15840723.

- PMID 17202163.

- ISBN 0-632-03712-1.

- ISBN 0-8053-3040-2.

- ISBN 1-55581-176-0.

- ISBN 0-89573-614-4.

- ^ PMID 12999684.

- PMID 13034700.

- S2CID 4172829.

- PMID 13888713.

- PMID 14187389.

- PMID 15840723.

- PMID 5312500.

- PMID 5312501.

- PMID 24141096.

- PMID 4332003.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". The Nobel Foundation. 1978. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

for the discovery of restriction enzymes and their application to problems of molecular genetics

- PMID 358198.

- PMID 7628720.

- S2CID 19989648.

- S2CID 31128438.

- ^ Cooper S (2003). "Restriction Map". bioweb.uwlax.edu. University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ PMID 11557805.

- ISBN 0-12-175551-7.

- S2CID 222199041.

- ^ PMID 8336674.

- PMID 4949033.

- PMID 6267988.

- ^ a b Types of Restriction Endonucleases | NEB

- ^ S2CID 1929381.

- S2CID 29672999.

- ^ PMID 10839821.

- ISBN 3-540-20502-0.

- ISBN 978-0-470-08766-4.

- PMID 22610857.

- PMID 24966351.

- PMID 11557806.

- S2CID 4354056.

- PMID 12595133.

- ^ S2CID 3888761.

- S2CID 17960960.

- PMID 8577732.

- S2CID 205484701.

- PMID 19404258.

- S2CID 4323298.

- PMID 18554175.

- PMID 19628861.

- PMID 21029755.

- PMID 20660643.

- PMID 20699274.

- PMID 24906146.

- ^ "Revolutionizing Biotechnology with Artificial Restriction Enzymes". Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2021. (reporting on Programmable DNA-Guided Artificial Restriction Enzymes)

- PMID 20545354.

- ISBN 9783642188510.

- PMID 4588280.

- PMID 12654995.

- ^ Geerlof A. "Cloning using restriction enzymes". European Molecular Biology Laboratory - Hamburg. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ISBN 0-87969-576-5.

- PMID 18330346.

- PMID 15980518.

- ^ "Mapping". Nature.

- ISBN 0-7167-4684-0.

- PMID 24597865.

- ^ Wayengera M (2003). "HIV and Gene Therapy: The proposed [R-M enzymatic] model for a gene therapy against HIV". Makerere Med J. 38: 28–30.

- ^ Wayengera M, Kajumbula H, Byarugaba W (2007). "Frequency and site mapping of HIV-1/SIVcpz, HIV-2/SIVsmm and Other SIV gene sequence cleavage by various bacteria restriction enzymes: Precursors for a novel HIV inhibitory product". Afr J Biotechnol. 6 (10): 1225–1232.

- PMID 22718830.

- PMID 24284874.

- PMID 18724932.

- PMID 18396111.

- PMID 6243774.

- PMID 2835753.

- ^ ISBN 0-7167-4366-3.

- ^ "Stu I from Streptomyces tubercidicus". Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- PMID 6260571.

External links

- DNA Restriction Enzymes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Firman K (2007-11-24). "Type I Restriction-Modification". University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Goodsell DS (2000-08-01). "Restriction Enzymes". Molecule of the Month. RCSB Protein Data Bank. Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Simmer M, Secko D (2003-08-01). "Restriction Endonucleases: Molecular Scissors for Specifically Cutting DNA". The Science Creative Quarterly. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Roberts RJ, Vincze T, Posfai, J, Macelis D. "REBASE". Archived from the original on 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

Restriction Enzyme Database