Returns from Troy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

| Trojan War |

|---|

|

The Returns from Troy are the stories of how the Greek leaders returned after their victory in the

The sack of Troy

The Achaeans entered the city using the

Of the women of the royal family,

The Returns

News of Troy's fall quickly reached the Achaean kingdoms through

But though the message was brought fast and with ease, the heroes were not to return this way. The Gods were very angry over the destruction of their temples and other sacrilegious acts by the Achaeans and decided that most would not return. A storm fell on the returning fleet off

- Agamemnon had made it back to his kingdom safely with Cassandra in his possession after some stormy weather. He and Cassandra were slain by Aegisthus (in the oldest versions of the story) or by Clytemnestra or by both of them. Electra and Orestes later avenged their father, but Orestes was the one who was chased by the Furies. See below for further details.

- Nestor, who had the best conduct in Troy and did not take part in the looting, was the only hero who had a good, fast and safe return.[9] Those of his army that survived the war also reached home with him safely.

- The archer ).

- In Roman myths the kingdom of Phtia was taken over by Helenus, who married Andromache. They offered hospitality to other Trojan refugees, including Aeneas who paid a visit there during his wanderings.

- According to Roman traditions, he had some adventures and founded a colony in Italy.

- Petilia, Old Crimissa, and Chone, between Croton and Thurii.[20] After making war on the Leucanians, he founded there a sanctuary of Apollo the Wanderer to whom also he dedicated his bow.[21]

- For Homer, Asia Minor where he died.[24]

Among the lesser Achaeans very few reached their homes.

- Cinyps river.[25]

- Antiphus, son of Thessalus from Cos, settled in Pelasgiotis and renamed it Thessaly after his father Thessalus.[21]

- Prothous from Magnesia settled in Crete[25]

- Melos[21]

- Theseus' descendants ruled Athens for four more generations.[28]

- The army of Apollonia.

- Balearic islands.[21]

- Podalirius, following the instructions of the oracle at Delphi, settled in Caria.[29]

House of Atreus

According to the Odyssey, Menelaus's fleet was blown by storms to Crete and Egypt where they were unable to sail away because the wind was calm.[30] Only 5 of his ships survived.[31] Menelaus had to catch Proteus, a shape-shifting sea god to find out what sacrifices to which gods he would have to make to guarantee safe passage.[32] Proteus told Menelaus that he was destined for Elysium (the Fields of the Blessèd) after his death. Menelaus returned to Sparta with Helen 8 years after he had left Troy.[33]

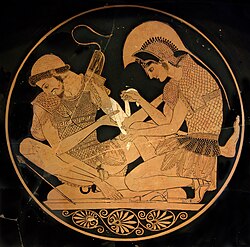

Agamemnon returned home with Cassandra to Mycenae. His wife Clytemnestra (Helen's sister) was having an affair with Aegisthus, son of Thyestes, Agamemnon's cousin who had conquered Argos before Agamemnon himself retook it. Possibly out of vengeance for the death of Iphigenia, Clytemnestra plotted with her lover to kill Agamemnon. Cassandra foresaw this murder, and warned Agamemnon, but he disregarded her. He was killed, either at a feast or in his bath[34] according to different versions. Cassandra was also killed.[35] Agamemnon's son Orestes, who had been away, returned and conspired with his sister Electra to avenge their father.[36] He killed Clytemnestra and Aegisthus and succeeded to his father's throne yet he was chased by the Furies until he was acquitted by Athena.[37][38]

The Odyssey

Odysseus (or Ulysses), attempting to travel home, underwent a series of trials, tribulations and setbacks that stretched his journey to ten years' time. These are detailed in Homer's epic poem the Odyssey.

At first they landed in the land of the Ciconians in

The rest then set sail and landed at the land of Polyphemus, son of Poseidon. After a few were killed by him Odysseus blinded him and managed to escape, but earned Poseidon's wrath.

They went next to the isle of Aeolus, god of winds. Odysseus was received hospitably by the Aeolus who gave him a favorable wind and a bag that contained the unfavorable wind. When Odysseus fell asleep in sight of Ithaca his crew opened the bag, and the ships were driven away.

In the next of the Laestrygonians next they neared, where the cannibalistic inhabitants sank his fleet (except Odysseus' ship) and ate the crew.

Next they landed on Circe's island, who transformed most of the crew into pigs, but Odysseus managed to force her to transform them back and left.

Odysseus wished to speak to Tiresias, so he went the river Acheron in Hades, where they performed sacrifices which allowed them to speak to the dead. They gave them advice on how to proceed. Then, he went to Circe's island again.

From there he set sail through the pass of the Sirens, whose sweet singing lure sailors to their doom. He had stopped up the ears of his crew with wax, and Odysseus alone listened while tied to the mast.

Next was the pass of

Odysseus was washed ashore on Ogygia, where the nymph Calypso lived. She made him her lover for seven years and would not let him leave, promising him immortality if he stayed. On behalf of Athena, Zeus intervened and sent Hermes to tell Calypso to let Odysseus go.

Odysseus left on a small raft furnished with provisions of water, wine and food by Calypso, only to be hit by a storm and washed up on the island of

There Odysseus traveled disguised as an old beggar by Athena he was recognized by his dog Argus, who died in his lap. Then he discovered his wife Penelope had been faithful to him all these years despite the countless suitors, including Antinous and Eurymachus, that were eating and spending his property all these years. With his son Telemachus' help and that of Athena and Eumaeus the swineherd, killed all of them except Medon, who had been polite to Penelope, and Phemius, a local singer who had only been forced to help the suitors against Penelope. Penelope tested him by saying they'd move his immovable bed, which correctly Odysseus pointed out couldn't be done, and he forgave her. On the next day the suitor's relatives, led by Eupeithes, the father of the suitor Antinous, tried to take revenge on him but they were stopped by Athena.

Years later Odysseus' son by Circe,

See also

References

- ^ Homer Iliad Γ.347-353

- ^ Apollodorus Epitome 5.21

- ^ Proclus Chrestomathy 2, The Sack of Ilium; Apollodorus Epitome 5.22

- ^ Apollodorus Epitome 5.23

- ^ Euripides, Hecabe 109

- ^ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiv.210-328

- ^ Aeschylus, Agamemnon 268-317

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.11

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.24

- ^ Apollodorus Epitome 6.6

- ^ Scholiast on Homer's Iliad 13.66

- ^ Pausanias 1.28.11

- ^ Pausanias 8.15.7

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.12

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.13

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.14

- ^ Plutarch, Parallel lives Greeks and Romans 23

- ^ Pausanias 1.28.9

- ^ Tzetzes ad Lycophronem 609

- ^ Strabo 6.1.3

- ^ a b c d Apollodorus, Epitome 6.15b

- ^ Homer Odyssey γ 1.91

- ^ Vergil, Aeneid 3.400

- ^ Scholiast on Homer Odyssey ν 259

- ^ a b Apollodorus, Epitome 6.15a

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.15

- ^ Pausanias 8.5.2

- ^ Pausanias 1.3.3

- ^ Pausanias 3.26.10; Apollodorus, Epitome 6.18

- ^ Odyssey δ 360

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.24

- ^ Odyssey δ 382

- ^ Apollodorus Epitome 6.29

- ^ Pausanias 2.16.6

- ^ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.23

- ^ Odyssey α 30, 298

- ^ Pausanias 2.16.7

- ^ Sophocles Electra 1405

- ^ "Solinus, Polyhistor". ToposText.