Reverse proxy

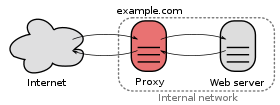

In computer networks, a reverse proxy (or surrogate server) is a proxy server that appears to any client (such as a browser) to be an ordinary web server, but in reality merely acts as an intermediary that forwards the client's requests to one or more ordinary web servers.[1][2] Reverse proxies help increase scalability, performance, resilience, and security, but they also carry a number of risks.

Description

Companies that run web servers often set up reverse proxies to facilitate the communication between an Internet user's browser and the web servers. An important advantage of doing so is that the web servers can be hidden behind a firewall on a company-internal network, and only the reverse proxy needs to be directly exposed to the Internet.

Reverse proxies should not be confused with

Implementations

Reverse proxy servers are implemented in popular open-source web servers, such as Apache, Nginx, and Caddy, which makes them a hybrid between a reverse proxy server and a web server. Dedicated reverse proxy servers, such as the open source software HAProxy and Squid, are used by some of the biggest websites on the Internet.

Uses

Large websites and content delivery networks use reverse proxies, together with other techniques, to balance the load between internal servers. Reverse proxies can keep a cache of static content, which further reduces the load on these internal servers and the internal network. It is also common for reverse proxies to add features such as compression or TLS encryption to the communication channel between the client and the reverse proxy.[3]

- Reverse proxies can inspect HTTP headers, which, for example, allows them to present a single IP addressto the Internet while relaying requests to different internal servers based on the URL of the HTTP request.

- Reverse proxies can hide the existence and characteristics of origin servers. This can make it more difficult to determine the actual location of the origin server / website and, for instance, more challenging to initiate legal action such as takedowns or block access to the website, as the IP address of the website may not be immediately apparent. Additionally, the reverse proxy may be located in a different jurisdiction with different legal requirements, further complicating the takedown process.

- Application firewall features can protect against common web-based attacks, like a denial-of-service attack (DoS) or distributed denial-of-service attacks (DDoS). Without a reverse proxy, removing malware or initiating takedowns (while simultaneously dealing with the attack) on one's own site, for example, can be difficult.

- In the case of secure websites, a web server may not perform TLS encryption itself, but instead offload the task to a reverse proxy that may be equipped with TLS acceleration hardware. (See TLS termination proxy.)

- A reverse proxy can distribute the load from incoming requests to several servers, with each server supporting its own application area. In the case of reverse proxying web servers, the reverse proxy may have to rewrite the URL in each incoming request in order to match the relevant internal location of the requested resource.

- A reverse proxy can reduce load on its origin servers by caching static content and dynamic content, known as web acceleration. Proxy caches of this sort can often satisfy a considerable number of website requests, greatly reducing the load on the origin server(s).

- A reverse proxy can optimize content by compressing it in order to speed up loading times.

- In a technique named "spoon-feeding",[4] a dynamically generated page can be produced all at once and served to the reverse proxy, which can then return it to the client a little bit at a time. The program that generates the page need not remain open, thus releasing server resources during the possibly extended time the client requires to complete the transfer.

- Reverse proxies can operate wherever multiple web-servers must be accessible via a single public IP address. The web servers listen on different ports in the same machine, with the same local IP address or, possibly, on different machines with different local IP addresses. The reverse proxy analyzes each incoming request and delivers it to the right server within the local area network.

- Reverse proxies can perform A/B testing and multivariate testing without placing JavaScript tags or code into pages.

- A reverse proxy can add access authentication to a web server that does not have any authentication.[5][6]

Risks

- A reverse proxy can track all IP addresses making requests through it and it can also read and modify any non-encrypted traffic. Thus, it can log passwords or inject malware, and might do so if compromised or run by a malicious party.

- When the transit traffic is TLS certificateand its corresponding private key, extending the number of systems that can have access to non-encrypted data and making it a more valuable target for attackers.

- The vast majority of external data breaches happen either when hackers succeed in abusing an existing reverse proxy that was intentionally deployed by an organisation, or when hackers succeed in converting an existing Internet-facing server into a reverse proxy server. Compromised or converted systems allow external attackers to specify where they want their attacks proxied to, enabling their access to internal networks and systems.

- Applications that were developed for the internal use of a company are not typically hardened to public standards and are not necessarily designed to withstand all hacking attempts. When an organisation allows external access to such internal applications via a reverse proxy, they might unintentionally increase their own attack surface and invite hackers.

- If a reverse proxy is not configured to filter attacks or it does not receive daily updates to keep its attack signature database up to date, a zero-dayvulnerability can pass through unfiltered, enabling attackers to gain control of the system(s) that are behind the reverse proxy server.

- Using the reverse proxy of a third party (e.g., triad of confidentiality, integrity and availabilityin the hands of the third party who operates the proxy.

- If a reverse proxy is fronting many different domains, its outage (e.g., by a misconfiguration or DDoS attack) could bring down all fronted domains.[7]

- Reverse proxies can also become a single point of failure if there is no other way to access the back end server.

See also

References

- ^ "Forward and reverse proxies". The Apache Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^

Reese, Will (September 2008). "Nginx: the high-performance web server and reverse proxy". Linux Journal (173).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Proxy servers and tunneling". MDN Web Docs. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "squid-cache wiki entry on "SpoonFeeding"". Francesco Chemolli. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Possible to add basic HTTP access authentication via HAProxy?". serverfault.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "forward_auth (Caddyfile directive) - Caddy Documentation". caddyserver.com. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Cloudflare outage knocks out major sites and services, including Discord". finance.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.