Rheumatic fever

| Rheumatic fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) |

myocardium) | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Fever, multiple painful joints, involuntary muscle movements, erythema marginatum[1] |

| Complications | Rheumatic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, infection of the valves[1] |

| Usual onset | 2–4 weeks after a streptococcal throat infection, age 5–14 years[2] |

| Causes | Autoimmune disease triggered by Streptococcus pyogenes[1] |

| Risk factors | Genetics, malnutrition, poverty[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and infection history[3] |

| Prevention | Antibiotics for strep throat, improved sanitation[1][4] |

| Treatment | Prolonged periods of antibiotics, valve replacement surgery, valve repair[1] |

| Frequency | 325,000 children a year[1] |

| Deaths | 319,400 (2015)[5] |

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain.[1] The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a streptococcal throat infection.[2] Signs and symptoms include fever, multiple painful joints, involuntary muscle movements, and occasionally a characteristic non-itchy rash known as erythema marginatum.[1] The heart is involved in about half of the cases.[1] Damage to the heart valves, known as rheumatic heart disease (RHD), usually occurs after repeated attacks but can sometimes occur after one.[1] The damaged valves may result in heart failure, atrial fibrillation and infection of the valves.[1]

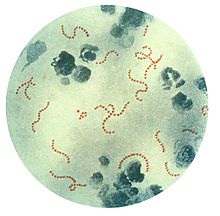

Rheumatic fever may occur following an infection of the throat by the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes.[1] If the infection is left untreated, rheumatic fever occurs in up to three percent of people.[6] The underlying mechanism is believed to involve the production of antibodies against a person's own tissues.[1] Due to their genetics, some people are more likely to get the disease when exposed to the bacteria than others.[1] Other risk factors include malnutrition and poverty.[1] Diagnosis of RF is often based on the presence of signs and symptoms in combination with evidence of a recent streptococcal infection.[3]

Treating people who have strep throat with

Rheumatic fever occurs in about 325,000 children each year and about 33.4 million people currently have rheumatic heart disease.

Signs and symptoms

The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a

Pathophysiology

Rheumatic fever is a

S. pyogenes has a

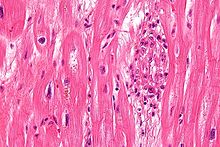

In rheumatic fever, these lesions can be found in any layer of the heart causing different types of

Rheumatic heart disease

Chronic rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is characterized by repeated inflammation with fibrinous repair. The cardinal anatomic changes of the valve include leaflet thickening, commissural fusion, and shortening and thickening of the tendinous cords.

Molecular mimicry occurs when epitopes are shared between host antigens and Streptococcus antigens.[21] This causes an autoimmune reaction against native tissues in the heart that are incorrectly recognized as "foreign" due to the cross-reactivity of antibodies generated as a result of epitope sharing. The valvular endothelium is a prominent site of lymphocyte-induced damage. CD4+ T cells are the major effectors of heart tissue autoimmune reactions in RHD.[22] Normally, T cell activation is triggered by the presentation of bacterial antigens. In RHD, molecular mimicry results in incorrect T cell activation, and these T lymphocytes can go on to activate B cells, which will begin to produce self-antigen-specific antibodies. This leads to an immune response attack mounted against tissues in the heart that have been misidentified as pathogens. Rheumatic valves display increased expression of VCAM-1, a protein that mediates the adhesion of lymphocytes.[23] Self-antigen-specific antibodies generated via molecular mimicry between human proteins and streptococcal antigens up-regulate VCAM-1 after binding to the valvular endothelium. This leads to the inflammation and valve scarring observed in rheumatic valvulitis, mainly due to CD4+ T cell infiltration.[23]

While the mechanisms of genetic predisposition remain unclear, a few genetic factors have been found to increase susceptibility to autoimmune reactions in RHD. The dominant contributors are a component of

Diagnosis

| Type | WBC (per mm3) | % neutrophils | Viscosity | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <200 | 0 | High | Transparent |

| Osteoarthritis | <5000 | <25 | High | Clear yellow |

| Trauma | <10,000 | <50 | Variable | Bloody |

| Inflammatory | 2,000–50,000 | 50–80 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Septic arthritis | >50,000 | >75 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Gonorrhea | ~10,000 | 60 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Tuberculosis | ~20,000 | 70 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Inflammatory: Arthritis, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever | ||||

The original method of diagnosing rheumatic heart disease was through heart auscultation, specifically listening for the sound of blood regurgitation from possibly dysfunctional valves. However, studies have shown that

Major criteria

- Joint manifestations are the unique clinical signs that have different implications for different population-risk categories : Only polyarthritis[42] (a temporary migrating inflammation of the large joints, usually starting in the legs and migrating upwards) is considered as a major criterion in low-risk populations, whereas monoarthritis, polyarthritis and polyarthralgia (joint pain without swelling) are all included as major criteria in high-risk populations.[34]

- Carditis: Carditis can involve the pericardium (pericarditis which resolves without sequelae), some regions of the myocardium (which might not provoke systolic dysfunction), and more consistently the endocardium in the form of valvulitis.[43] Carditis is diagnosed clinically (palpitations, shortness of breath, heart failure, or a new heart murmur) or by echocardiography/Doppler studies revealing mitral or aortic valvulitis. Both of clinical and subclinical carditis are now considered a major criterion.[34][43]

- Subcutaneous nodules: Painless, firm collections of collagen fibers over bones or tendons. They commonly appear on the back of the wrist, the outside elbow, and the front of the knees.[citation needed]

- macules, which spread outward and clear in the middle to form rings, which continue to spread and coalesce with other rings, ultimately taking on a snake-like appearance. This rash typically spares the face and is made worse with heat.[citation needed]

- Sydenham's chorea (St. Vitus' dance): A characteristic series of involuntary rapid movements of the face and arms. This can occur very late in the disease for at least three months from onset of infection.[citation needed]

Minor criteria

- Arthralgia: Polyarthralgia in low-risk populations and monoarthralgia in others.[34] However, joint manifestations cannot be considered in both major and minor categories in the same patient.[34]

- Fever: ≥ 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) in low-incidence populations and ≥ 38 °C (100.4 °F) in high-risk populations.[34]

- Raised C reactive protein (>3.0 mg/dL).[34]

- after accounting for age variability (Cannot be included if carditis is present as a major symptom)

Prevention

Rheumatic fever can be prevented by effectively and promptly treating

In those who have previously had rheumatic fever, antibiotics may be used in a preventative manner as

Vaccine

No vaccines are currently available to protect against S. pyogenes infection, although research is underway to develop one.[50] Difficulties in developing a vaccine include the wide variety of strains of S. pyogenes present in the environment and the large amount of time and number of people that will be needed for appropriate trials for safety and efficacy of the vaccine.[51]

Treatment

The management of rheumatic fever is directed toward the reduction of inflammation with

Infection

People with positive cultures for Streptococcus pyogenes should be treated with penicillin as long as allergy is not present. The use of antibiotics will not alter cardiac involvement in the development of rheumatic fever.[42] Some suggest the use of benzathine benzylpenicillin.[citation needed]

Monthly injections of long-acting penicillin must be given for a period of five years in patients having one attack of rheumatic fever. If there is evidence of carditis, the length of therapy may be up to 40 years. Another important cornerstone in treating rheumatic fever includes the continual use of low-dose antibiotics (such as penicillin, sulfadiazine, or erythromycin) to prevent recurrence.[citation needed]

Inflammation

Aspirin at high doses has historically been used for treatment of rheumatic fever.

Heart failure

Some patients develop significant

Epidemiology

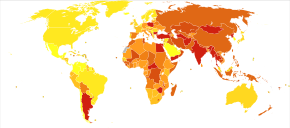

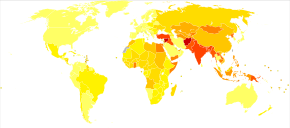

About 33 million people are affected by rheumatic heart disease with an additional 47 million having asymptomatic damage to their heart valves.[46] As of 2010 globally it resulted in 345,000 deaths, down from 463,000 in 1990.[57]

In Western countries, rheumatic fever has become fairly rare since the 1960s, probably due to the widespread use of antibiotics to treat streptococcus infections. While it has been far less common in the United States since the beginning of the 20th century, there have been a few outbreaks since the 1980s.[58] The disease is most common among Indigenous Australians (particularly in central and northern Australia), Māori, and Pacific Islanders, and is also common in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Indian subcontinent, and North Africa.[59]

Rheumatic fever primarily affects children between ages 5 and 17 years and occurs approximately 20 days after strep throat. In up to a third of cases, the underlying strep infection may not have caused any symptoms.[citation needed]

The rate of development of rheumatic fever in individuals with untreated strep infection is estimated to be 3%. The incidence of recurrence with a subsequent untreated infection is substantially greater (about 50%).[60] The rate of development is far lower in individuals who have received antibiotic treatment. Persons who have had a case of rheumatic fever have a tendency to develop flare-ups with repeated strep infections.[citation needed]

The recurrence of rheumatic fever is relatively common in the absence of maintenance of low dose antibiotics, especially during the first three to five years after the first episode. Recurrent bouts of rheumatic fever can lead to valvular heart disease. Heart complications may be long-term and severe, particularly if valves are involved. In countries in Southeast-Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Oceania, the percentage of people with rheumatic heart disease detected by listening to the heart was 2.9 per 1000 children and by echocardiography it was 12.9 per 1000 children.[61][62][63][64] To assist in the identification of RHD in low resource settings and where prevalence of GAS infections is high, the World Heart Federation has developed criteria for RHD diagnosis using echocardiography, supported by clinical history if available.[65] The WHF additionally defines criteria for use in people younger than age 20 to diagnose "borderline" RHD, as identification of cases of RHD among children is a priority to prevent complications and progression.[46] However, spontaneous regression is more likely in borderline RHD than in definite cases, and its natural history may vary between populations.[46]

Echocardiographic

See also

- Rapid strep test

- Chronic post–RF arthropathy – joint changes that may arise following multiple episodes of rheumatic fever, also called Jaccoud's arthropathy[68]

References

- ^ S2CID 20197628.

- ^ PMID 22318812.

- ^ a b "Rheumatic Fever 1997 Case Definition". cdc.gov. 3 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ PMID 34881426.

- ^ PMID 27733281.

- rheumatic heart disease.

- PMID 27733282.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- PMID 25530442.

- PMID 1775859.

- ^ "rheumatic fever" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "4.2 Biocompatibility and the Relationship to Standards: Meaning and Scope of Biomaterials Testing". Comprehensive Biomaterials II. Elsevier. 2017. pp. 7–29.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-2403-3.

- ^ "Streptococcus pyogenes – Pathogen Safety Data Sheets". Public Health Agency of Canada. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- PMID 16622036.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8. Archived from the originalon 10 September 2005.

- PMID 14170842.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-59259-918-9.

- S2CID 13330575.

- S2CID 16987808.

- S2CID 16987808.

- PMID 2786783.

- ^ PMID 11133385.

- ^ PMID 14680508.

- S2CID 252865544.

- PMID 18602696.

- PMID 18400978.

- S2CID 202570077.

- ISBN 978-0-19-991494-4.

- PMID 30725799. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- PMID 28163427.

- .

- from the original on 31 December 2005.

- ^ S2CID 46209822.

- ^ "Antistreptolysin O (ASO)". 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Anti-DNase B". 28 June 2021.

- ^ Parrillo SJ. "Rheumatic Fever". eMedicine. DO, FACOEP, FACEP. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- PMID 1404745.

- S2CID 23052280.

- PMID 23703332.

- ^ a b Ed Boon, Davidson's General Practice of Medicine, 20th edition. P. 617.

- ^ a b c "WHO | Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ S2CID 51702921.

- ^ Aly A (2008). "Rheumatic Fever". Core Concepts of Pediatrics. University of Texas. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ PMID 19246689.

- ^ PMID 27886787.

- ^ PMID 27773865.

- ^ PMID 37603629. National Library of Medicine Bookshelf ID NBK594238.

- ^ PMID 24603191.

- ^ "Collaboration aims for rheumatic fever vaccine". sciencemediacentre.co.nz. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ "Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR) – Group A Streptococcus". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Aspirin Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- PMID 14517527.

- PMID 28621087.

- ^ PMID 26017576. Art. No. CD003176.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- S2CID 1541253.

- ^ "Rheumatic fever". Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. NLM/NIH. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Rheumatic heart disease". Menzies Institute for Medical Research. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-7087-3.

- S2CID 28936439.

- PMID 25433627.

- PMID 27437661.

- PMID 22626741.

- PMID 22371105.

- PMID 33471029.

- ^ PMID 34767321.

- PMID 5496065.

External links

- "Jones major criteria". Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.