Richard F. Heck

Richard F. Heck | |

|---|---|

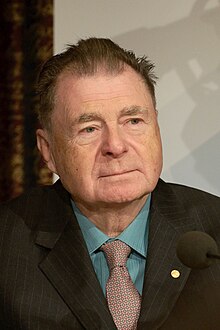

Heck in 2010 | |

| Born | Richard Frederick Heck August 15, 1931 Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 9, 2015 (aged 84) Manila, Philippines |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | UCLA (BS, PhD) |

| Known for | Heck reaction |

| Spouse | Socorro Nardo-Heck (died 2012) |

| Awards | Glenn T. Seaborg Medal (2011) Nobel Prize in Chemistry (2010) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | University of Delaware Hercules ETH Zurich De La Salle University |

| Thesis | Methoxyl and aryl groups in substitution and rearrangement (1955) |

| Doctoral advisor | Saul Winstein |

Richard Frederick Heck (August 15, 1931 – October 9, 2015) was an American chemist noted for the discovery and development of the

is an example of a compound that is prepared industrially using the Heck reaction.For his work in

Early life and education

Heck was born in

Career

At Hercules, Heck soon became interested in

During the early 1970s, Tsutomu Mizoroki independently reported the use of the less toxic aryl halides as the coupling partner in the reaction.[7][8] Heck became a professor of chemistry at the University of Delaware's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in 1971, where he continued to improve the transformation, developing it into a powerful synthetic method for organic synthesis.[3]

The importance of this reaction grew as it was taken up by others in the organic synthesis community.[9][10] In 1982, Heck was able to write an Organic Reactions chapter that covered all the known instances in just 45 pages.[11] By 2002, applications had grown to the extent that the Organic Reactions chapter published that year, limited to intramolecular Heck reactions, covered 377 pages. These reactions, a small part of the total, couple two parts of the same molecule.[12] The reaction is now one of the most widely used methods for the creation of

Heck's contributions were not limited to the activation of halides by the oxidative addition of palladium. He was the first to fully characterize a π-allyl metal complex,[4] and the first to elucidate the mechanism of alkene hydroformylation.[5]

Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions

Heck's work set the stage for a variety of other

Of the several reactions developed by Heck, the greatest societal impact has been from the palladium-catalyzed coupling of an alkyne with an aryl halide. This is the reaction that was used to couple fluorescent dyes to DNA bases, allowing the automation of DNA sequencing and the examination of the human genome; the reaction also allows biologically important proteins to be tracked.[16][17] In Sonogashira's original report of what is now known as the Sonogashira coupling, his group modified an alkyne coupling procedure previously reported by Heck, by adding a copper(I) salt.[18]

Later life and death

Heck retired from the University of Delaware in 1989, where he became the Willis F. Harrington Professor Emeritus in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Its annual lectureship was named in his honor in 2004. In 2005, he was awarded the

Heck died on October 9, 2015, in Manila in a public hospital. His wife predeceased him by 2 years.[25][26]

Honorary degrees

Heck received honorary doctorates from the Faculty of Pharmacy at Uppsala University in 2011[27] and De La Salle University in 2012.[28]

See also

References

- ^ a b Press release 6 October 2010, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, retrieved October 6, 2010

- Boston Globe.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- ^ .

- . and six further articles, pages 5526–5548

- .

- .

- PMID 11749313.

- PMID 21677934.

- ISBN 0471264180.

- ISBN 0471264180.

- OCLC 233173519.

- PMID 22573393.

- .

- S2CID 46474691.

- PMID 25025771.

- .

- ^ "Richard Heck, professor emeritus and Nobel laureate, dies". udel.edu. October 10, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "2006 ACS National Award Winners". C&EN. 84 (6): 34–38. February 6, 2006. Archived from the original on August 6, 2007..

- ^ "Richard F. Heck – Interview". Nobelprize.org. October 7, 2010. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ "BBC News – Molecule building work wins Nobel". bbc.co.uk. October 6, 2010. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ Suarez, Larissa Mae (October 7, 2010). "US scientist residing in Philippines wins 2010 chemistry Nobel". GMANews.tv.

- ^ Quismundo, Tarra. "He's the only Nobel winner living in RP". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010.

- New York Times. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Francisco, Rosemarie (October 10, 2015). "Nobel laureate chemist Richard Heck, 84, dies in Manila". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "Honorary Doctors of the Faculty of Pharmacy". uu.se. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ "Make Life Simple" Through Chemistry, Nobel Laureate Dr. Richard Heck's Goal"". nast.ph. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

External links

- Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Delaware

- Richard F. Heck on Nobelprize.org