Heart failure

| Heart failure | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Congestive heart failure (CHF), congestive cardiac failure (CCF) |

| Frequency | 40 million (2015),[8] 1–2% of adults (developed countries)[6][9] |

| Deaths | 35% risk of death in first year[10] |

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a

Common causes of heart failure include

Diagnosis is based on symptoms, physical findings, and

Heart failure is a common, costly, and potentially fatal condition,[22] and is the leading cause of hospitalization and readmission in older adults.[23][24] Heart failure often leads to more drastic health impairments than failure of other, similarly complex organs such as the kidneys or liver.[25] In 2015, it affected about 40 million people worldwide.[8] Overall, heart failure affects about 2% of adults,[22] and more than 10% of those over the age of 70.[6] Rates are predicted to increase.[22] The risk of death in the first year after diagnosis is about 35%, while the risk of death in the second year is less than 10% in those still alive.[10] The risk of death is comparable to that of some cancers.[10] In the United Kingdom, the disease is the reason for 5% of emergency hospital admissions.[10] Heart failure has been known since ancient times; it is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus around 1550 BCE.[26]

Definition

Heart failure is not a disease but a syndrome – a combination of signs and symptoms – caused by the failure of the heart to pump blood to support the circulatory system at rest or during activity.[6]: 3612 [3] It develops when the heart fails to properly fill with blood during diastole, resulting in a decrease in intracardiac pressures or in ejection during systole, reducing cardiac output to the rest of the body.[6]: 3612 [4]: e272 The filling failure and high intracardiac pressure can lead to fluid accumulation in the veins and tissue. This manifests as water retention and swelling due to fluid accumulation (edema) called congestion. Impaired ejection can lead to inadequate blood flow to the body tissues, resulting in ischemia.[27][28]

Signs and symptoms

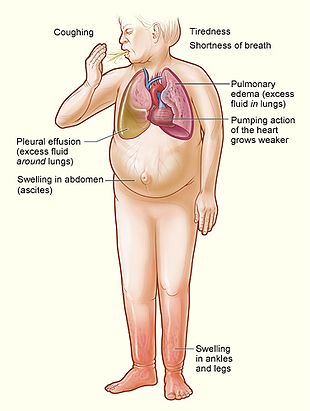

Congestive heart failure is a

Symptoms of heart failure are traditionally divided into left-sided and right-sided because the left and right ventricles supply different parts of the circulation. In biventricular heart failure, both sides of the heart are affected. Left-sided heart failure is the more common.[30]

Left-sided failure

The left side of the heart takes oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it to the rest of the

Other signs of left ventricular failure include a laterally displaced apex beat (which occurs when the heart is enlarged) and a gallop rhythm (additional heart sounds), which may be heard as a sign of increased blood flow or increased intracardiac pressure. Heart murmurs may indicate the presence of valvular heart disease, either as a cause (e.g., aortic stenosis) or as a consequence (e.g., mitral regurgitation) of heart failure.[32]

Reverse insufficiency of the left ventricle causes congestion in the blood vessels of the lungs, so that symptoms are predominantly respiratory. Reverse insufficiency can be divided into the failure of the left atrium, the left ventricle, or both within the left circuit. Patients will experience

Right-sided failure

Right-sided heart failure is often caused by pulmonary heart disease (cor pulmonale), which is typically caused by issues with pulmonary circulation such as pulmonary hypertension or pulmonic stenosis. Physical examination may reveal pitting peripheral edema, ascites, liver enlargement, and spleen enlargement. Jugular venous pressure is frequently assessed as a marker of fluid status, which can be accentuated by testing hepatojugular reflux. If the right ventricular pressure is increased, a parasternal heave which causes the compensatory increase in contraction strength may be present.[35]

Backward failure of the right ventricle leads to congestion of systemic capillaries. This generates excess fluid accumulation in the body. This causes swelling under the skin (peripheral edema or anasarca) and usually affects the dependent parts of the body first, causing foot and ankle swelling in people who are standing up and sacral edema in people who are predominantly lying down. Nocturia (frequent night-time urination) may occur when fluid from the legs is returned to the bloodstream while lying down at night. In progressively severe cases, ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity causing swelling) and liver enlargement may develop. Significant liver congestion may result in impaired liver function (congestive hepatopathy), jaundice, and coagulopathy (problems of decreased or increased blood clotting).[36]

Biventricular failure

Dullness of the lung fields when percussed and reduced breath sounds at the base of the lungs may suggest the development of a pleural effusion (fluid collection between the lung and the chest wall). Though it can occur in isolated left- or right-sided heart failure, it is more common in biventricular failure because pleural veins drain into both the systemic and pulmonary venous systems. When unilateral, effusions are often right-sided.[37]

If a person with a failure of one ventricle lives long enough, it will tend to progress to failure of both ventricles. For example, left ventricular failure allows pulmonary edema and pulmonary hypertension to occur, which increase stress on the right ventricle. Though still harmful, right ventricular failure is not as deleterious to the left side.[38]

Causes

Since heart failure is a syndrome and not a disease, establishing the underlying cause is vital to diagnosis and treatment.[39][30] In heart failure, the structure or the function of the heart or in some cases both are altered.[6]: 3612 Heart failure is the potential end stage of all heart diseases.[40]

Common causes of heart failure include

High-output heart failure

Acute decompensation

Chronic stable heart failure may easily decompensate. This most commonly results from a concurrent illness (such as

Other factors that may worsen CHF include: anemia, hyperthyroidism, excessive fluid or salt intake, and medication such as

Medications

A number of medications may cause or worsen the disease. This includes

By inhibiting the formation of

Breast cancer patients are at high risk of heart failure due to several factors.[55] After analysing data from 26 studies (836,301 patients), the recent meta-analysis found that breast cancer survivors demonstrated a higher risk heart failure within first ten years after diagnosis (hazard ratio = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.1, 1.33).[56] The pooled incidence of heart failure in breast cancer survivors was 4.44 (95% CI 3.33-5.92) per 1000 person-years of follow-up.[56]

Supplements

Certain

Pathophysiology

Heart failure is caused by any condition that reduces the efficiency of the heart muscle, through damage or overloading. Over time, these increases in workload, which are mediated by long-term activation of neurohormonal systems such as the renin–angiotensin system and the sympathoadrenal system, lead to fibrosis, dilation, and structural changes in the shape of the left ventricle from elliptical to spherical.[22]

The heart of a person with heart failure may have a reduced force of contraction due to overloading of the

Diagnosis

No diagnostic criteria have been agreed on as the gold standard for heart failure, especially heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

In the

The European Society of Cardiology defines the diagnosis of heart failure as symptoms and signs consistent with heart failure in combination with "objective evidence of cardiac structural or functional abnormalities".[6] This definition is consistent with an international 2021 report termed "Universal Definition of Heart Failure".[6]: 3613 Score-based algorithms have been developed to help in the diagnosis of HFpEF, which can be challenging for physicians to diagnose.[6]: 3630 The AHA/ACC/HFSA defines heart failure as symptoms and signs consistent with heart failure in combination with shown "structural and functional alterations of the heart as the underlying cause for the clinical presentation", for HFmrEF and HFpEF specifically requiring "evidence of spontaneous or provokable increased left ventricle filling pressures".[4]: e276–e277

Algorithms

The European Society of Cardiology has developed a diagnostic algorithm for HFpEF, named HFA-PEFF.[6]: 3630 [58] HFA-PEFF considers symptoms and signs, typical clinical demographics (obesity, hypertension, diabetes, elderly, atrial fibrillation), and diagnostic laboratory tests, ECG, and echocardiography.[4]: e277 [58]

Classification

"Left", "right" and mixed heart failure

One historical method of categorizing heart failure is by the side of the heart involved (left heart failure versus right heart failure). Right heart failure was thought to compromise blood flow to the lungs compared to left heart failure compromising blood flow to the aorta and consequently to the brain and the remainder of the body's systemic circulation. However, mixed presentations are common and left heart failure is a common cause of right heart failure.[59]

By ejection fraction

More accurate classification of heart failure type is made by measuring ejection fraction, or the proportion of blood pumped out of the heart during a single contraction.[60] Ejection fraction is given as a percentage with the normal range being between 50 and 75%.[60] The types are:

- Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF): Synonyms no longer recommended are "heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction" and "systolic heart failure".[61] HFrEF is associated with an ejection fraction less than 40%.[62]

- Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), previously called "heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction",[63] is defined by an ejection fraction of 41–49%.[63]

- Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): Synonyms no longer recommended include "diastolic heart failure" and "heart failure with normal ejection fraction."[10][18] HFpEF occurs when the left ventricle contracts normally during systole, but the ventricle is stiff and does not relax normally during diastole, which impairs filling.[10]

Heart failure may also be classified as acute or chronic. Chronic heart failure is a long-term condition, usually kept stable by the treatment of symptoms.

Several terms are closely related to heart failure and may be the cause of heart failure, but should not be confused with it.

Ultrasound

An

-

Ultrasound showing severe systolic heart failure[69]

-

Ultrasound showing severe systolic heart failure[69]

-

Ultrasound of the lungs showing edema due to severe systolic heart failure[69]

-

Ultrasound showing severe systolic heart failure[69]

-

Ultrasound showing severe systolic heart failure[69]

Chest X-ray

-

Congestive heart failure with small bilateral effusions

-

Kerley B lines

Electrophysiology

An

Blood tests

N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) is the favoured biomarker for the diagnosis of heart failure, according to guidelines published 2018 by NICE in the UK.[3] Brain natriuretic peptide 32 (BNP) is another biomarker commonly tested for heart failure.[72][6][73] An elevated NT-proBNP or BNP is a specific test indicative of heart failure. Additionally, NT-proBNP or BNP can be used to differentiate between causes of dyspnea due to heart failure from other causes of dyspnea. If myocardial infarction is suspected, various cardiac markers may be used.

Hyponatremia (low serum sodium concentration) is common in heart failure. Vasopressin levels are usually increased, along with renin, angiotensin II, and catecholamines to compensate for reduced circulating volume due to inadequate cardiac output. This leads to increased fluid and sodium retention in the body; the rate of fluid retention is higher than the rate of sodium retention in the body, this phenomenon causes hypervolemic hyponatremia (low sodium concentration due to high body fluid retention). This phenomenon is more common in older women with low body mass. Severe hyponatremia can result in accumulation of fluid in the brain, causing cerebral edema and intracranial hemorrhage.[74]

Angiography

Staging

Heart failure is commonly stratified by the degree of functional impairment conferred by the severity of the heart failure, as reflected in the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification.[76] The NYHA functional classes (I–IV) begin with class I, which is defined as a person who experiences no limitation in any activities and has no symptoms from ordinary activities. People with NYHA class II heart failure have slight, mild limitations with everyday activities; the person is comfortable at rest or with mild exertion. With NYHA class III heart failure, a marked limitation occurs with any activity; the person is comfortable only at rest. A person with NYHA class IV heart failure is symptomatic at rest and becomes quite uncomfortable with any physical activity. This score documents the severity of symptoms and can be used to assess response to treatment. While its use is widespread, the NYHA score is not very reproducible and does not reliably predict the walking distance or exercise tolerance on formal testing.[77]

In its 2001 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association working group introduced four stages of heart failure:[78]

- Stage A: People at high risk for developing HF in the future, but no functional or structural heart disorder

- Stage B: A structural heart disorder, but no symptoms at any stage

- Stage C: Previous or current symptoms of heart failure in the context of an underlying structural heart problem, but managed with medical treatment

- Stage D: Advanced disease requiring hospital-based support, a heart transplant, or palliative care

The ACC staging system is useful since stage A encompasses "pre-heart failure" – a stage where intervention with treatment can presumably prevent progression to overt symptoms. ACC stage A does not have a corresponding NYHA class. ACC stage B would correspond to NYHA class I. ACC stage C corresponds to NYHA class II and III, while ACC stage D overlaps with NYHA class IV.

- The degree of coexisting illness: i.e. heart failure/systemic hypertension, heart failure/pulmonary hypertension, heart failure/diabetes, heart failure/kidney failure, etc.

- Whether the problem is primarily increased venous back pressure (preload), or failure to supply adequate arterial perfusion (afterload)

- Whether the abnormality is due to low cardiac output with high systemic vascular resistanceor high cardiac output with low vascular resistance (low-output heart failure vs. high-output heart failure)

Histopathology

Histopathology can diagnose heart failure in autopsies. The presence of siderophages indicates chronic left-sided heart failure, but is not specific for it.[79] It is also indicated by congestion of the pulmonary circulation.

Prevention

A person's risk of developing heart failure is inversely related to level of

Diabetes is a major risk factor for heart failure. For women with Coronary Heart disease (CHD), diabetes was the strongest risk factor for heart failure.[83] Diabetic women with depressed creatinine clearance or elevated BMI were at the highest risk of heart failure. While the annual incidence rate of heart failure for non-diabetic women with no risk factors is 0.4%, the annual incidence rate for diabetic women with elevated body mass index (BMI) and depressed creatinine clearance was 7% and 13%, respectively.[84]

Management

Treatment focuses on improving the symptoms and preventing the progression of the disease. Reversible causes of heart failure also need to be addressed (e.g.

Acute decompensation

In

Chronic management

The goals of the treatment for people with chronic heart failure are the prolongation of life, prevention of acute decompensation, and reduction of symptoms, allowing for greater activity.

Heart failure can result from a variety of conditions. In considering therapeutic options, excluding reversible causes is of primary importance, including

Advance care planning

The latest evidence indicates that advance care planning (ACP) may help to increase documentation by medical staff regarding discussions with participants, and improve an individual's depression.[89] This involves discussing an individual's future care plan in consideration of the individual's preferences and values. The findings are however, based on low-quality evidence.[89]

Monitoring

The various measures often used to assess the progress of people being treated for heart failure include

Lifestyle

Behavior modification is a primary consideration in chronic heart failure management program, with

Exercise and physical activity

Exercise should be encouraged and tailored to suit individual's capabilities. A meta-analysis found that centre-based group interventions delivered by a physiotherapist are helpful in promoting physical activity in HF.[95] There is a need for additional training for physiotherapists in delivering behaviour change intervention alongside an exercise programme. An intervention is expected to be more efficacious in encouraging physical activity than the usual care if it includes Prompts and cues to walk or exercise, like a phone call or a text message. It is extremely helpful if a trusted clinician provides explicit advice to engage in physical activity (Credible source). Another highly effective strategy is to place objects that will serve as a cue to engage in physical activity in the everyday environment of the patient (Adding object to the environment; e.g., exercise step or treadmill). Encouragement to walk or exercise in various settings beyond CR (e.g., home, neighbourhood, parks) is also promising (Generalisation of target behaviour). Additional promising strategies are Graded tasks (e.g., gradual increase in intensity and duration of exercise training), Self-monitoring, Monitoring of physical activity by others without feedback, Action planning, and Goal-setting.[96] The inclusion of regular physical conditioning as part of a cardiac rehabilitation program can significantly improve quality of life and reduce the risk of hospital admission for worsening symptoms, but no evidence shows a reduction in mortality rates as a result of exercise.

Home visits and regular monitoring at heart-failure clinics reduce the need for hospitalization and improve life expectancy.[97]

Medication

Quadruple medical therapy using a combination of

There is no convincing evidence for pharmacological treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).[6] Medication for HFpEF is symptomatic treatment with diuretics to treat congestion.[6] Managing risk factors and comorbidities such as hypertension is recommended in HFpEF.[6]

Inhibitors of the

In people who are intolerant of ACE-I and ARB or who have significant kidney dysfunction, the use of combined hydralazine and a long-acting nitrate, such as isosorbide dinitrate, is an effective alternate strategy. This regimen has been shown to reduce mortality in people with moderate heart failure.[105] It is especially beneficial in the black population.[a][105]

Use of a

SGLT2 inhibitors are used for heart failure.[4]

Other medications

Second-line medications for CHF do not confer a mortality benefit. Digoxin is one such medication. Its narrow therapeutic window, a high degree of toxicity, and the failure of multiple trials to show a mortality benefit have reduced its role in clinical practice. It is now used in only a small number of people with refractory symptoms, who are in atrial fibrillation, and/or who have chronic hypotension.[106][107]

Diuretics have been a mainstay of treatment against symptoms of fluid accumulation, and include diuretics classes such as

Anemia is an independent factor in mortality in people with chronic heart failure. Treatment of anemia significantly improves quality of life for those with heart failure, often with a reduction in severity of the NYHA classification, and also improves mortality rates.

The decision to anticoagulate people with HF, typically with left ventricular ejection fractions <35% is debated, but generally, people with coexisting atrial fibrillation, a prior embolic event, or conditions that increase the risk of an embolic event such as amyloidosis, left ventricular noncompaction, familial dilated cardiomyopathy, or a thromboembolic event in a first-degree relative.[78]

Vasopressin receptor antagonists can also be used to treat heart failure. Conivaptan is the first medication approved by US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of euvolemic hyponatremia in those with heart failure.[74] In rare cases hypertonic 3% saline together with diuretics may be used to correct hyponatremia.[74]

Ivabradine is recommended for people with symptomatic heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction who are receiving optimized guideline-directed therapy (as above) including the maximum tolerated dose of beta-blocker, have a normal heart rhythm and continue to have a resting heart rate above 70 beats per minute.[111] Ivabradine has been found to reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure exacerbations in this subgroup of people with heart failure.[111]

Implanted devices

In people with severe cardiomyopathy (left ventricular ejection fraction below 35%), or in those with recurrent VT or malignant arrhythmias, treatment with an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD) is indicated to reduce the risk of severe life-threatening arrhythmias. The AICD does not improve symptoms or reduce the incidence of malignant arrhythmias but does reduce mortality from those arrhythmias, often in conjunction with antiarrhythmic medications. In people with left ventricular ejection (LVEF) below 35%, the incidence of

Cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) is a treatment for people with moderate to severe left ventricular systolic heart failure (NYHA class II–IV), which enhances both the strength of ventricular contraction and the heart's pumping capacity. The CCM mechanism is based on stimulation of the cardiac muscle by nonexcitatory electrical signals, which are delivered by a pacemaker-like device. CCM is particularly suitable for the treatment of heart failure with normal QRS complex duration (120 ms or less) and has been demonstrated to improve the symptoms, quality of life, and exercise tolerance.[21][112][113][114][115] CCM is approved for use in Europe, and was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States in 2019.[116][117][118]

About one-third of people with

Surgical therapies

People with the most severe heart failure may be candidates for ventricular assist devices, which have commonly been used as a bridge to heart transplantation, but have been used more recently as a destination treatment for advanced heart failure.[121]

In select cases, heart transplantation can be considered. While this may resolve the problems associated with heart failure, the person must generally remain on an immunosuppressive regimen to prevent rejection, which has its own significant downsides.[122] A major limitation of this treatment option is the scarcity of hearts available for transplantation.

Palliative care

People with heart failure often have significant symptoms, such as shortness of breath and chest pain. Palliative care should be initiated early in the HF trajectory, and should not be an option of last resort.[123] Palliative care can not only provide symptom management, but also assist with advanced care planning, goals of care in the case of a significant decline, and making sure the person has a medical power of attorney and discussed his or her wishes with this individual.[124] A 2016 and 2017 review found that palliative care is associated with improved outcomes, such as quality of life, symptom burden, and satisfaction with care.[123][125]

Without transplantation, heart failure may not be reversible and heart function typically deteriorates with time. The growing number of people with stage IV heart failure (intractable symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest pain at rest despite optimal medical therapy) should be considered for palliative care or hospice, according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.[124]

Prognosis

Prognosis in heart failure can be assessed in multiple ways, including clinical prediction rules and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Clinical prediction rules use a composite of clinical factors such as laboratory tests and blood pressure to estimate prognosis. Among several clinical prediction rules for prognosticating acute heart failure, the 'EFFECT rule' slightly outperformed other rules in stratifying people and identifying those at low risk of death during hospitalization or within 30 days.[126] Easy methods for identifying people that are low-risk are:

- ADHERE Tree rule indicates that people with systolic blood pressureat least 115 mm Hg have less than 10% chance of inpatient death or complications.

- BWH rule indicates that people with systolic blood pressure over 90 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 30 or fewer breaths per minute, serum sodium over 135 mmol/L, and no new ST–T wave changes have less than 10% chance of inpatient death or complications.

A very important method for assessing prognosis in people with advanced heart failure is cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX testing). CPX testing is usually required prior to heart transplantation as an indicator of prognosis. CPX testing involves measurement of exhaled oxygen and carbon dioxide during exercise. The peak oxygen consumption (VO2 max) is used as an indicator of prognosis. As a general rule, a VO2 max less than 12–14 cc/kg/min indicates poor survival and suggests that the person may be a candidate for a heart transplant. People with a VO2 max <10 cc/kg/min have a clearly poorer prognosis. The most recent International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines[127] also suggest two other parameters that can be used for evaluation of prognosis in advanced heart failure, the heart failure survival score and the use of a criterion of VE/VCO2 slope > 35 from the CPX test. The heart failure survival score is calculated using a combination of clinical predictors and the VO2 max from the CPX test.

Heart failure is associated with significantly reduced physical and mental health, resulting in a markedly decreased quality of life.[128][129] With the exception of heart failure caused by reversible conditions, the condition usually worsens with time. Although some people survive many years, progressive disease is associated with an overall annual mortality rate of 10%.[130]

Around 18 of every 1000 persons will experience an ischemic stroke during the first year after diagnosis of HF. As the duration of follow-up increases, the stroke rate rises to nearly 50 strokes per 1000 cases of HF by 5 years.[131]

Epidemiology

In 2022, heart failure affected about 64 million people globally.[132] Overall, around 2% of adults have heart failure.[22] In those over the age of 75, rates are greater than 10%.[22]

Rates are predicted to increase.[22] Increasing rates are mostly because of increasing lifespan, but also because of increased risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity) and improved survival rates from other types of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, valvular disease, and arrhythmias).[133][134][135] Heart failure is the leading cause of hospitalization in people older than 65.[136]

United States

In the United States, heart failure affects 5.8 million people, and each year 550,000 new cases are diagnosed.[137] In 2011, heart failure was the most common reason for hospitalization for adults aged 85 years and older, and the second-most common for adults aged 65–84 years.[138] An estimated one in five adults at age 40 will develop heart failure during their remaining lifetimes and about half of people who develop heart failure die within 5 years of diagnosis.[139] Heart failure – much higher in African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and recent immigrants from Eastern Europe countries – has been linked in these ethnic minority populations to high incidence of diabetes and hypertension.[140]

Nearly one of every four people (24.7%) hospitalized in the U.S. with congestive heart failure are readmitted within 30 days.[141] Additionally, more than 50% of people seek readmission within 6 months after treatment and the average duration of hospital stay is 6 days. Heart failure is a leading cause of hospital readmissions in the U.S. People aged 65 and older were readmitted at a rate of 24.5 per 100 admissions in 2011. In the same year, people under Medicaid were readmitted at a rate of 30.4 per 100 admissions, and uninsured people were readmitted at a rate of 16.8 per 100 admissions. These are the highest readmission rates for both categories. Notably, heart failure was not among the top-10 conditions with the most 30-day readmissions among the privately insured.[142]

United Kingdom

In the UK, despite moderate improvements in prevention, heart failure rates have increased due to population growth and ageing.[143] Overall heart failure rates are similar to the four most common causes of cancer (breast, lung, prostate, and colon) combined.[143] People from deprived backgrounds are more likely to be diagnosed with heart failure and at a younger age.[143]

Developing world

In tropical countries, the most common cause of heart failure is valvular heart disease or some type of cardiomyopathy. As underdeveloped countries have become more affluent, the incidences of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity have increased, which have in turn raised the incidence of heart failure.[citation needed]

Sex

Men have a higher incidence of heart failure, but the overall prevalence rate is similar in both sexes since women survive longer after the onset of heart failure.[144] Women tend to be older when diagnosed with heart failure (after menopause), they are more likely than men to have diastolic dysfunction, and seem to experience a lower overall quality of life than men after diagnosis.[144]

Ethnicity

Some sources state that people of Asian descent are at a higher risk of heart failure than other ethnic groups.[145] Other sources however have found that rates of heart failure are similar to rates found in other ethnic groups.[146]

History

For centuries, the disease entity which would include many cases of what today would be called heart failure was dropsy; the term denotes generalized edema, a major manifestation of a failing heart, though also caused by other diseases. Writings of ancient civilizations include evidence of their acquaintance with dropsy and heart failure: Egyptians were the first to use

One of the earliest treatments of heart failure, relief of swelling by bloodletting with various methods, including

Economics

In 2011, nonhypertensive heart failure was one of the 10 most expensive conditions seen during inpatient hospitalizations in the U.S., with aggregate inpatient hospital costs more than $10.5 billion.[162]

Heart failure is associated with a high health expenditure, mostly because of the cost of hospitalizations; costs have been estimated to amount to 2% of the total budget of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, and more than $35 billion in the United States.[163][164]

Research directions

Some research indicates that

The maintenance of heart function depends on appropriate gene expression that is regulated at multiple levels by epignetic mechanisms including DNA methylation and histone post-translational modification.[167][168] Currently, an increasing body of research is directed at understanding the role of perturbations of epigenetic processes in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrotic scarring.[167][168]

Notes

References

- ISBN 978-0-7020-4900-2. Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Congestive heart failure (CHF)". Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ S2CID 247882156.

- S2CID 235707832.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ PMID 22741186.

- ^ PMID 27733282.

- ^ S2CID 38678826.

- ^ PMID 22741186.

- ^ "What is Heart Failure?". www.heart.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-1080-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-7746-6.

- ^ from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ PMID 22741186.

- ^ from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ PMID 30695817.

- ^ PMID 22741186.

- ^ PMID 22965336.

- ^ PMID 24265466.

- ^ S2CID 34893221.

- PMID 23386663.

- PMID 22179539.

- ^ "Do we expect the body to be a "One Hoss Shay"?". The Evolution and Medicine Review. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-19-957772-9. Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- PMID 29226815.

- ^ PMID 29885957.

- ^ "Pulse pressure". Cleveland Clinic. 28 July 2021. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

A narrow pulse pressure — sometimes called a low pulse pressure — is where your pulse pressure is one-fourth or less of your systolic pressure (the top number). This happens when your heart isn't pumping enough blood, which is seen in heart failure and certain heart valve diseases.

- ^ a b Types of heart failure. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021 – via National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - from the original on 13 March 2021, retrieved 11 May 2022

- ^ "Heart Murmur: Types & Causes". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "What is Exercise Intolerance?". WebMD. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Heart Failure Signs and Symptoms". heart.org. American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- PMC 7123149.

- from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- PMC 7122716.

- ^ Ponikowski et al. 2016, p. 2136.

- ^ PMID 10617530.

- PMID 26383716.

- PMID 30072851.

- PMID 26215765.

- PMID 32327422.

- PMID 32293640.

- ^ a b "high-output heart failure" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- PMID 26567494.

- PMID 35158878.

- S2CID 20912905.

- (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- PMID 23726390.

- PMID 30165516.

- PMID 31668726.

- ^ PMID 27400984.

- PMID 26987914.

- ^ PMID 37499186.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-3256-8.

- ^ from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "Heart Failure: Signs and Symptoms". UCSF Medical Center. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Ejection Fraction". Heart Rhythm Society. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- PMID 35460242.

- ^ "Ejection Fraction Heart Failure Measurement". American Heart Association. 11 February 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b "2021 ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure". European Society of Cardiology. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- PMID 19324967.

- S2CID 253409509.

- PMID 34685747.

- S2CID 52280408.

- PMID 34019437.

- ^ a b c d e "UOTW #48 – Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 23 May 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- PMID 25176151.

- ISBN 978-0-07-147693-5.

- from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- S2CID 35294486.

- ^ from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Angiography – Consumer Information – InsideRadiology". InsideRadiology. 23 September 2016. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Criteria Committee, New York Heart Association (1964). Diseases of the heart and blood vessels. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis (6th ed.). Boston: Little, Brown. p. 114.

- PMID 17005715.

- ^ PMID 16160202.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974892-1. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- PMID 26438781.

- ^ "Heart Failure: Am I at Risk, and Can I Prevent It?". Webmd. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "2019 Updated Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Guidelines Announced - Johns Hopkins Medicine". clinicalconnection.hopkinsmedicine.org. 17 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Thom, T., Haase, N., Rosamond, W., Howard, V., Rumsfeld, J., & Manolio, T. et al. (2006). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2006 Update. Circulation, 113(6). https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.105.171600 Archived 9 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo, K., Lin, F., & Vittinghoff, E. (2005). Predictors of heart failure among women with coronary disease. ACC Current Journal Review, 14(2), 35–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accreview.2004.12.100 Archived 9 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 224780668.

- ^ "Acute heart failure with dyspnoea. First-choice treatments". Prescrire International. 27 (194): 160–162. 2018.

- PMID 27072018.

- S2CID 73725232.

- ^ PMID 32104908.

- PMID 16061743.

- PMID 28108430.

- from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "Lifestyle Changes for Heart Failure". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015.

- S2CID 53241717.

- PMID 34108272.

- PMID 34108272.

- S2CID 262525144.

- S2CID 232299815.

- PMID 33653703.

- ISBN 978-0-323-08787-2.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 108: Chronic heart failure – managements (ARBs) of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. London, August 2010.

- PMID 27098105.

- (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- PMID 24599093.

- ^ a b c National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) (August 2010). "Chapter 5: Treating heart failure". Chronic Heart Failure: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Management in Primary and Secondary Care (Partial Update [Internet]. ed.). London (UK): Royal College of Physicians. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Congestive Heart Failure". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 7 August 2020. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Digoxin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- S2CID 7441258.

- PMID 19522961.

- ^ Nunez-Gil MI, Peraira-Moral MJ (19 January 2012). "Anaemia in heart failure: intravenous iron therapy". e-Journal of the ESC Council for Cardiology Practice. 10 (16). Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ PMID 28455343.

- PMID 23229137.

- PMID 24975782.

- S2CID 10484257.

- PMID 25662055.

- ^ Kuschyk J (2014). "Der Besondere Stellenwert der Kardialen Kontraktilitätsmodulation in der Devicetherapie". Herzmedizin. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT01381172 for "Evaluate Safety and Efficacy of the OPTIMIZER System in Subjects With Moderate-to-Severe Heart Failure: FIX-HF-5C (FIX-HF-5C)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "FDA Approves Optimizer Smart System for Heart Failure Patients". Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology (DAIC). 21 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- PMID 23741058.

- (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- PMID 23135811.

- PMID 15596559.

- ^ PMID 28982506.

- ^ PMID 20026792.

- PMID 27893131.

- PMID 17449141.

- PMID 16962464.

- PMID 11847161.

- PMID 12445536.

- S2CID 1481349.

- PMID 17675064.

- PMID 35078371.

- ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6. Archivedfrom the original on 14 October 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-4377-2788-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4377-2788-3.

- PMID 10618565.

- PMID 21060326.

- ^ Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C (September 2013). "Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #162. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- PMID 23239837.

- ^ "Heart disease facts". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 May 2023. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. Hospitals by Diagnosis, 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #153. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2013. "Statistical Brief #153". Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ PMID 29174292.

- ^ S2CID 41171172.

- ISBN 978-1-4471-6656-6.

- PMID 27541646.

- from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ S2CID 5216806.

- ^ PMID 15685783.

- ^ PMID 31620262.

- ^ S2CID 210890303.

- PMID 4896254.

- PMID 9185118.

- ^ PMID 13437417.

- PMID 28510104.

- ^ PMID 15880332.

- PMID 8672051.

- ^ a b c d Ventura HO. "A Glimpse of Yesterday: Treatment of "Dropsy" (Slides with Transcript)". Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- PMID 16760707.

- S2CID 116245349.

- PMID 18610472.

- ^ Torio CM, Andrews RM. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. August 2013. "Statistical Brief #160". Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- S2CID 12765307.

- PMID 18086926.

- ^ PMID 28012165.

- PMID 24778175.

- ^ a b Papait R, Serio S, Condorelli G. Role of the Epigenome in Heart Failure. Physiol Rev. 2020 Oct 1;100(4):1753-1777. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2019. Epub 2020 Apr 23. PMID 32326823

- ^ a b Zhao K, Mao Y, Li Y, Yang C, Wang K, Zhang J. The roles and mechanisms of epigenetic regulation in pathological myocardial remodeling. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Aug 26;9:952949. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.952949. PMID 36093141; PMCID: PMC9458904

External links

- Heart failure, American Heart Association – information and resources for treating and living with heart failure

- Heart Failure Matters – patient information website of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology

- Heart failure in children by Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK

- "Heart Failure". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure - Guideline Hub at American College of Cardiology, jointly with the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. JACC article link, quick references, slides, perspectives, education, apps and tools, and patient resources. April, 2022

- 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure - European Society of Cardiology resource webpage with links to Full text and related materials, scientific presentation at ESC Congress 2021, news article, TV interview, app, slide set, and ESC Pocket Guidelines; plus previous versions. August, 2021.

![Ultrasound showing severe systolic heart failure[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/UOTW_48_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_5.jpg/120px-UOTW_48_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_5.jpg)