River delta

A river delta is a landform shaped like a triangle, created by the deposition of sediment that is carried by a river and enters slower-moving or stagnant water.[1][2] This occurs at a river mouth, when it enters an ocean, sea, estuary, lake, reservoir, or (more rarely) another river that cannot carry away the supplied sediment. It is so named because its triangle shape resembles the uppercase Greek letter delta, Δ. The size and shape of a delta are controlled by the balance between watershed processes that supply sediment, and receiving basin processes that redistribute, sequester, and export that sediment.[3][4] The size, geometry, and location of the receiving basin also plays an important role in delta evolution.

River deltas are important in human

Etymology

A river delta is so named because the shape of the

As a

Formation

River deltas form when a river carrying sediment reaches a body of water, such as a lake, ocean, or a

As the gradient of the river channel decreases, the amount of shear stress on the bed decreases, which results in the deposition of sediment within the channel and a rise in the channel bed relative to the floodplain. This destabilizes the river channel. If the river breaches its natural levees (such as during a flood), it spills out into a new course with a shorter route to the ocean, thereby obtaining a steeper, more stable gradient.[13] Typically, when the river switches channels in this manner, some of its flow remains in the abandoned channel. Repeated channel-switching events build up a mature delta with a distributary network.

Another way these distributary networks form is from the deposition of

In both of these cases, depositional processes force redistribution of deposition from areas of high deposition to areas of low deposition. This results in the smoothing of the planform (or map-view) shape of the delta as the channels move across its surface and deposit sediment. Because the sediment is laid down in this fashion, the shape of these deltas approximates a fan. The more often the flow changes course, the shape develops as closer to an ideal fan, because more rapid changes in channel position result in more uniform deposition of sediment on the delta front. The Mississippi and Ural River deltas, with their bird's-feet, are examples of rivers that do not avulse often enough to form a symmetrical fan shape. Alluvial fan deltas, as seen by their name, avulse frequently and more closely approximate an ideal fan shape.

Most large river deltas discharge to intra-cratonic basins on the trailing edges of passive margins due to the majority of large rivers such as the

There are many other lesser factors that could explain why the majority of river deltas form along passive margins rather than active margins. Along active margins, orogenic sequences cause tectonic activity to form over-steepened slopes, brecciated rocks, and volcanic activity resulting in delta formation to exist closer to the sediment source.[16][17] When sediment does not travel far from the source, sediments that build up are coarser grained and more loosely consolidated, therefore making delta formation more difficult. Tectonic activity on active margins causes the formation of river deltas to form closer to the sediment source which may affect channel avulsion, delta lobe switching, and auto cyclicity.[17] Active margin river deltas tend to be much smaller and less abundant but may transport similar amounts of sediment.[16] However, the sediment is never piled up in thick sequences due to the sediment traveling and depositing in deep subduction trenches.[16]

Types

Deltas are typically classified according to the main control on deposition, which is a combination of river, wave, and tidal processes,[18][19] depending on the strength of each.[20] The other two factors that play a major role are landscape position and the grain size distribution of the source sediment entering the delta from the river.[21]

Fluvial-dominated deltas

Fluvial-dominated deltas are found in areas of low tidal range and low wave energy.

Fluvial-dominated deltas are further distinguished by the relative importance of the inertia of rapidly flowing water, the importance of turbulent bed friction beyond the river mouth, and buoyancy. Outflow dominated by inertia tend to form Gilbert type deltas. Outflow dominated by turbulent friction is prone to channel bifurcation, while buoyancy-dominated outflow produces long distributaries with narrow subaqueous natural levees and few channel bifurcations.[23]

The modern Mississippi River delta is a good example of a fluvial-dominated delta whose outflow is buoyancy-dominated. Channel abandonment has been frequent, with seven distinct channels active over the last 5000 years. Other fluvial-dominated deltas include the Mackenzie delta and the Alta delta.[14]

Gilbert deltas

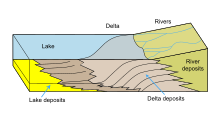

A Gilbert delta (named after Grove Karl Gilbert) is a type of fluvial-dominated[24] delta formed from coarse sediments, as opposed to gently-sloping muddy deltas such as that of the Mississippi. For example, a mountain river depositing sediment into a freshwater lake would form this kind of delta.[25] [26] It is commonly a result of homopycnal flow.[22] Such deltas are characterized by a tripartite structure of topset, foreset, and bottomset beds. River water entering the lake rapidly deposits its coarser sediments on the submerged face of the delta, forming steeping dipping foreset beds. The finer sediments are deposited on the lake bottom beyond this steep slope as more gently dipping bottomset beds. Behind the delta front, braided channels deposit the gently dipping beds of the topset on the delta plain.[27][28]

While some authors describe both lacustrine and marine locations of Gilbert deltas,

Wave-dominated deltas

In wave dominated deltas, wave-driven sediment transport controls the shape of the delta, and much of the sediment emanating from the river mouth is deflected along the coast line.[18] The relationship between waves and river deltas is quite variable and largely influenced by the deepwater wave regimes of the receiving basin. With a high wave energy near shore and a steeper slope offshore, waves will make river deltas smoother. Waves can also be responsible for carrying sediments away from the river delta, causing the delta to retreat.[6] For deltas that form further upriver in an estuary, there are complex yet quantifiable linkages between winds, tides, river discharge, and delta water levels.[30][31]

Tide-dominated deltas

Erosion is also an important control in tide-dominated deltas, such as the Ganges Delta, which may be mainly submarine, with prominent sandbars and ridges. This tends to produce a "dendritic" structure.[32] Tidal deltas behave differently from river-dominated and wave-dominated deltas, which tend to have a few main distributaries. Once a wave-dominated or river-dominated distributary silts up, it is abandoned, and a new channel forms elsewhere. In a tidal delta, new distributaries are formed during times when there is a lot of water around – such as floods or storm surges. These distributaries slowly silt up at a more or less constant rate until they fizzle out.[32]

Tidal freshwater deltas

A tidal freshwater delta

Estuaries

Other rivers, particularly those on coasts with significant

Inland deltas

In rare cases the river delta is located inside a large valley and is called an

In some cases, a river flowing into a flat arid area splits into channels that evaporate as it progresses into the desert. The Okavango Delta in Botswana is one example.[47] See endorheic basin.

Mega deltas

The generic term mega delta can be used to describe very large Asian river deltas, such as the

Sedimentary structure

The formation of a delta is complicated, multiple, and cross-cutting over time, but in a simple delta three main types of bedding may be distinguished: the bottomset beds, foreset/frontset beds, and topset beds. This three part structure may be seen in small scale by

- The bottomset beds are created from the lightest suspended particles that settle farthest away from the active delta front, as the river flow diminishes into the standing body of water and loses energy. This suspended load is deposited by sediment gravity flow, creating a turbidite. These beds are laid down in horizontal layers and consist of the finest grain sizes.

- The foreset beds in turn are deposited in inclined layers over the bottomset beds as the active lobe advances. Foreset beds form the greater part of the bulk of a delta, (and also occur on the lee side of sand dunes).[51] The sediment particles within foreset beds consist of larger and more variable sizes, and constitute the bed load that the river moves downstream by rolling and bouncing along the channel bottom. When the bed load reaches the edge of the delta front, it rolls over the edge, and is deposited in steeply dipping layers over the top of the existing bottomset beds. Under water, the slope of the outermost edge of the delta is created at the angle of repose of these sediments. As the foresets accumulate and advance, subaqueouslandslides occur and readjust overall slope stability. The foreset slope, thus created and maintained, extends the delta lobe outward. In cross section, foresets typically lie in angled, parallel bands, and indicate stages and seasonal variations during the creation of the delta.

- The topset beds of an advancing delta are deposited in turn over the previously laid foresets, truncating or covering them. Topsets are nearly horizontal layers of smaller-sized sediment deposited on the top of the delta and form an extension of the landward alluvial plain.[51] As the river channels meander laterally across the top of the delta, the river is lengthened and its gradient is reduced, causing the suspended load to settle out in nearly horizontal beds over the delta's top. Topset beds are subdivided into two regions: the upper delta plain and the lower delta plain. The upper delta plain is unaffected by the tide, while the boundary with the lower delta plain is defined by the upper limit of tidal influence.[52]

Existential threats to deltas

Human activities in both deltas and the

The extensive anthropogenic activities in deltas also interfere with

While nearly all deltas have been impacted to some degree by humans, the Nile Delta and Colorado River Delta are some of the most extreme examples of the devastation caused to deltas by damming and diversion of water.[61][62]

Historical data documents show that during the Roman Empire and Little Ice Age (times where there was considerable anthropogenic pressure), there was significant sediment accumulation in deltas. The industrial revolution has only amplified the impact of humans on delta growth and retreat.[63]

Deltas in the economy

Ancient deltas are a benefit to the economy due to their well sorted

Urban areas and human habitation tends to locate in lowlands near water access for transportation and

Examples

The Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta, which spans most of Bangladesh and West Bengal and empties into the Bay of Bengal, is the world's largest delta.[66]

The

Deltas on Mars

Researchers have found a number of examples of deltas that formed in Martian lakes. Finding deltas is a major sign that Mars once had large amounts of water. Deltas have been found over a wide geographical range. Below are pictures of a few.[67]

-

Delta in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

-

Delta in Lunae Palus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

-

Delta in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle as seen by THEMIS

-

Probable delta inEberswalde crater, as seen by Mars Global Surveyor. Image in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle.

See also

- Alluvial fan – Fan-shaped deposit of sediment

- Avulsion (river) – Rapid abandonment of a river channel and formation of a new channel

- Estuary – Partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water

- Levee – Ridge or wall to hold back water

- Nile Delta – Delta produced by the Nile River at its mouth in the Mediterranean Sea

- Regressive delta

- Pearl River Delta – Complex delta in south-east China

References

- ^ Miall, A. D. 1979. Deltas. in R. G. Walker (ed) Facies Models. Geological Association of Canada, Hamilton, Ontario.

- ^ Elliot, T. 1986. Deltas. in H. G. Reading (ed.). Sedimentary environments and facies. Backwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

- S2CID 140714394.

- ^ S2CID 129080402.

- ISSN 1439-037X.

- ^ .

- S2CID 253145418. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ S2CID 143811840.

- ^ "Word Stories: Unexpected Relatives for Xmas". Druide. January 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-22. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ^ "How a Delta Forms Where River Meets Lake". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Dr. Gregory B. Pasternack – Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: TFD Modeling". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ISBN 0131547283.

- ^ Slingerland, R. and N. D. Smith (1998), "Necessary conditions for a meandering-river avulsion", Geology (Boulder), 26, 435–438.

- ^ a b Boggs 2006, p. 295.

- ISBN 9781405177832.

- ^ S2CID 22727856.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Galloway, W.E., 1975, Process framework for describing the morphologic and stratigraphic evolution of deltaic depositional systems, in Brousard, M.L., ed., Deltas, Models for Exploration: Houston Geological Society, Houston, Texas, pp. 87–98.

- ^ Nienhuis, J.H., Ashton, A.D., Edmonds, D.A., Hoitink, A.J.F., Kettner, A.J., Rowland, J.C. and Törnqvist, T.E., 2020. Global-scale human impact on delta morphology has led to net land area gain. Nature, 577(7791), pp.514-518.

- ^ Perillo, G. M. E. 1995. Geomorphology and Sedimentology of Estuaries. Elsevier Science B.V., New York.

- .

- ^ a b c Boggs 2006, p. 293.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 294.

- ^ Boggs 2006, pp. 293–294.

- ^ a b c Characteristics of deltas. (Available archived at [1] – checked Dec 2008.)

- ISBN 2-7108-0802-1. Editions TECHNIP, 2002. Partial texton Google Books.

- ^ Gilbert, G.K. (1885). The topographic features of lake shores. US Government Printing Office. pp. 104–107. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- S2CID 129299341.

- ^ ISBN 1-55791-668-3. Pages 2–17. Partial texton Google Books.

- ^ "Dr. Gregory B. Pasternack – Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: TFD Hydrometeorology". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- .

- ^ a b Fagherazzi S., 2008, Self-organization of tidal deltas, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 105 (48): 18692–18695,

- ^ "Gregory B. Pasternack – Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: Tidal Freshwater Deltas". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- OCLC 49850378.

- S2CID 25962433.

- .

- S2CID 85961542.

- JSTOR 211476.

- .

- S2CID 85128464.

- .

- .

- .

- S2CID 84968414.

- S2CID 111027461.

- .

- S2CID 33284178.

- .

- S2CID 205251150.

- ^ D.G.A Whitten, The Penguin Dictionary of Geology (1972)

- ^ AGI(1984)

- ^ Hori, K. and Saito, Y. Morphology and Sediments of Large River Deltas. Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo Geographical Society, 2003

- ISSN 0272-7714.

- ^ ISSN 1752-0908.

- ISSN 1748-9326.

- S2CID 128976925.

- PMID 30344619.

- S2CID 129784677.

- S2CID 210166330.

- PMID 31822705.

- ISSN 1687-4285.

- PMID 24646976.

- PMID 23722597.

- ^ "Mineral Photos – Sand and Gravel". Mineral Information Institute. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- ^ A., Stefan (2017-05-22). "Why are cities located where they are?". This City Knows. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ "Appendix A: The Major River Deltas Of The World" (PDF). Louisiana State University. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- ^ Irwin III, R. et al. 2005. An intense terminal epoch of widespread fluvial activity on early Mars: 2. Increased runoff and paleolake development. Journal of Geophysical Research: 10. E12S15

Bibliography

- Renaud, F. and C. Kuenzer 2012: The Mekong Delta System – Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta, Springer, , pp. 7–48

- KUENZER C. and RENAUD, F. 2012: Climate Change and Environmental Change in River Deltas Globally. In (eds.): Renaud, F. and C. Kuenzer 2012: The Mekong Delta System – Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta, Springer, , pp. 7–48

- Ottinger, M.; Kuenzer, C.; LIU; Wang, S.; Dech, S. (2013). "Monitoring Land Cover Dynamics in the Yellow River Delta from 1995 to 2010 based on Landsat 5 TM". Applied Geography. 44: 53–68. .

External links

- Louisiana State University Geology – World Deltas

- http://www.wisdom.eoc.dlr.de WISDOM Water related Information System for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong Delta

- Wave-dominated river deltas on coastalwiki.org – A coastalwiki.org page on wave-dominated river deltas