Romain Gary

Romain Gary | |

|---|---|

La vie devant soi | |

| Notable awards | Prix Goncourt (1956 and 1975) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

Romain Gary (pronounced

Early life

Gary was born Roman Kacew (

Career

Despite completing all parts of his course successfully, Gary was the only one of almost 300 cadets in his class not to be commissioned as an officer. He believed the military establishment was distrustful of him because he was a foreigner and a

As Émile Ajar

In a memoir published in 1981, Gary's nephew Paul Pavlowitch claimed that Gary also produced several works under the pseudonym Émile Ajar. Gary recruited Pavlowitch to portray Ajar in public appearances, allowing Gary to remain unknown as the true producer of the Ajar works, and thus enabling him to win the 1975 Goncourt Prize, a second win in violation of the prize's usual rules.[12]

Gary also published under the pseudonyms Shatan Bogat and Fosco Sinibaldi.[12]

Literary work

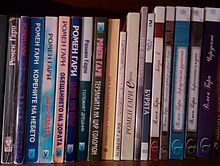

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the

In addition to his success as a novelist, he wrote the screenplay for the motion picture The Longest Day and co-wrote and directed the film Kill! (1971),[16] which starred his wife at the time, Jean Seberg. In 1979, he was a member of the jury at the 29th Berlin International Film Festival.[17]

Diplomatic career

After the end of the hostilities, Gary began a career as a

Personal life and final years

Gary's first wife was the British writer,

After learning that Jean Seberg had had an affair with Clint Eastwood, Gary challenged him to a duel, but Eastwood declined.[19]

Gary died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on 2 December 1980 in Paris. He left a note which said that his death had no relation to Seberg's suicide the previous year. He also stated in his note that he was Émile Ajar.[20]

Gary was cremated in Père Lachaise Cemetery and his ashes were scattered in the Mediterranean Sea near Roquebrune-Cap-Martin.[21]

Legacy

The name of Romain Gary was given to a promotion of the École nationale d'administration (2003–2005), the Institut d'études politiques de Lille (2013), the Institut régional d'administration de Lille (2021–2022) and the Institut d'études politiques de Strasbourg (2001–2002), in 2006 at Place Romain-Gary in the 15th arrondissement of Paris and at the Nice Heritage Library. The French Institute in Jerusalem also bears the name of Romain Gary.

On 16 May 2019, his work appeared in two volumes in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade under the direction of Mireille Sacotte.

In 2007, a statue of Romualdas Kvintas, «The Boy with a Galoche», was unveiled, depicting the 9-year-old little hero of the Promise of Dawn, preparing to eat a shoe to seduce his little neighbor, Valentina. It is placed in Vilnius, in front of the Basanavičius, where the novelist lived.

A plaque to his name is affixed in the Pouillon building of the Faculty of Law and Political Science of Aix-Marseille where he studied.

In 2022, Denis Ménochet portrayed Gary in White Dog (Chien blanc), a film adaptation by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette of Gary's 1970 book.[22]

Bibliography

As Romain Gary

- French: Éducation européenne (1945); translated as Forest of Anger

- French: Tulipe (1946); republished and modified in 1970.

- Le Grand Vestiaire (1949); translated as The Company of Men (1950)

- Les Couleurs du jour (1952); translated as The Colors of the Day (1953); filmed as The Man Who Understood Women (1959)

- Les Racines du ciel — 1956 Prix Goncourt; translated as The Roots of Heaven (1957); filmed as The Roots of Heaven(1958)

- Lady L (1958); self-translated and published in French in 1963; filmed as Lady L(1965)

- La Promesse de l'aube (1960); translated as Promise at Dawn (1961); filmed as Promise at Dawn (1970) and Promise at Dawn (2017)

- Johnie Cœur (1961, a theatre adaptation of "L'homme à la colombe")

- Gloire à nos illustres pionniers (1962, short stories); translated as "Hissing Tales" (1964)

- The Ski Bum (1965); self-translated into French as Adieu Gary Cooper (1969)

- Pour Sganarelle (1965, literary essay)

- Les Mangeurs d'étoiles (1966); self-translated into French and first published (in English) as The Talent Scout (1961)

- La Danse de Gengis Cohn (1967); self-translated into English as The Dance of Genghis Cohn

- La Tête coupable (1968); translated as The Guilty Head (1969)

- Chien blanc (1970); self-translated as White Dog (1970); filmed as White Dog (1982)

- Les Trésors de la mer Rouge (1971)

- Europa (1972); translated in English in 1978.

- The Gasp (1973); self-translated into French as Charge d'âme (1978)

- Les Enchanteurs (1973); translated as The Enchanters (1975)

- La nuit sera calme (1974, interview)

- Au-delà de cette limite votre ticket n'est plus valable (1975); translated as Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1977); filmed as Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1981)

- Clair de femme (1977); filmed as Womanlight (1979)

- La Bonne Moitié (1979, play)

- Les Clowns lyriques (1979); new version of the 1952 novel, Les Couleurs du jour (The Colors of the Day)

- Les Cerfs-volants (1980); translated as The Kites (2017)

- Vie et Mort d'Émile Ajar (1981, posthumous)

- L'Homme à la colombe (1984, definitive posthumous version)

- L'Affaire homme (2005, articles and interviews)

- L'Orage (2005, short stories and unfinished novels)

- Un humaniste, short story

As Émile Ajar

- Gros câlin(1979)

- La vie devant soi — 1975 Prix Goncourt; filmed as Madame Rosa (1977); translated as "Momo" (1978); re-released as The Life Before Us (1986). Filmed as The Life Ahead(2020)

- Pseudo(1976)

- L'Angoisse du roi Salomon (1979); translated as King Solomon (1983).

- Gros câlin – new version including final chapter of the original and never published version.

As Fosco Sinibaldi

- L'homme à la colombe (1958)

As Shatan Bogat

- Les têtes de Stéphanie (1974)

Filmography

As screenwriter

- 1958: The Roots of Heaven

- 1962: The Longest Day

- 1978: La vie devant soi

As actor

- 1936: Nitchevo – Le jeune homme au bastingage

- 1967: The Road to Corinth – (uncredited) (final film role)

As director

- 1968: Birds in Peru (Birds in Peru) starring Jean Seberg

- 1971: Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill! also starring Jean Seberg

In popular culture

- 2019: Seberg , joué par Yvan Attal

References

- ^ a b c Ivry, Benjamin (21 January 2011). "A Chameleon on Show". Daily Forward.

- ^ Romain Gary et la Lituanie Archived 26 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-2-207-24835-5, pp. ??

- ^ "Romain Gary". Encyclopédie sur la mort. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ISBN 0-8122-3646-7.

- ^ Schwartz, Madeleine. "Romain Gary: A Short Biography". The Harvard Advocate.

- ^ Passports of mother Mina Kacew and nurse-maid Aniela Voiciechowics. See Lithuaninan Central State Archives, F. 53, 122, 5351 and F. 15, 2, 1230. Copies of the documents are in the personal archive of a Moscow historian Alexander Vasin.

- ^ a b c d Marzorati 2018

- ^ "Romain Gary: The greatest literary conman ever?".

- ^ "Ordre de la Libération". Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Bellos, David (2010). Romain Gary: A Tall Story. pp. ??.

- ^ a b Prial, Frank J. (2 July 1981). "Gary won '75 Goncourt under Pseudonym 'Ajar'". The New York Times.

- ISBN 978-2-07-026351-6.

- ISBN 978-90-420-2426-7.

- ISBN 2-909240-70-3.

- ^ "Romain Gary". IMDb. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Berlinale 1979: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ Paris Match No.3136

- ^ Bellos, David (12 November 2010). "Romain Gary: au revoir et merci". The Telegraph. UK.

- ^ D. Bona, Romain Gary, Paris, Mercure de France-Lacombe, 1987, p. 397–398.

- ISBN 978-2-7491-1350-0

- ^ Demers, Maxime (2 November 2022). "«Chien blanc»: le goût du risque d'Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette". Le Journal de Montréal. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

Further reading

- Ajar, Émile (Romain Gary), Hocus Bogus, ISBN 978-0-300-14976-0 (translation of Pseudo by David Bellos, includes The Life and Death of Émile Ajar)

- Anissimov, Myriam, Romain Gary, le caméléon (Denoël 2004)

- ISBN 978-1-84343-170-1

- Bellos, David. 2009. The cosmopolitanism of Romain Gary. Darbair ir Dienos (Vilnius) 51:63–69.

- Gary, Romain, Promise at Dawn (Revived Modern Classic), ISBN 978-0-8112-1016-4

- ISBN 978-2-7427-0313-5

- Bona, Dominique, Romain Gary (Mercure de France, 1987) ISBN 2-7152-1448-0

- Cahier de l'Herne, Romain Gary (L'Herne, 2005)

- ISBN 978-2-07-274141-8

- Schoolcraft, Ralph W. (2002). Romain Gary: The Man Who Sold his Shadow. ISBN 0-8122-3646-7.

- ISBN 978-2-268-06724-7

- Marret, Carine, Romain Gary – Promenade à Nice (Baie des Anges, 2010)

- Marzorati, Michel (2018). Romain Gary: des racines et des ailes. Info-Pilote, 742 pp. 30–33

- Spire, Kerwin, Monsieur Romain Gary, Gallimard, 2021, ISBN 978-2-07-293006-5

- Stjepanovic-Pauly, Marianne. Romain Gary La mélancolie de l'enchanteur. Editions du Jasmin, ISBN 978-2-35284-141-8

External links

- Romain Gary at IMDb