Roman calendar

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. Although the term is primarily used for Rome's pre-Julian calendars, it is often used inclusively of the Julian calendar established by the reforms of the Dictator Julius Caesar and Emperor Augustus in the late 1st century BC.[a]

According to most Roman accounts,

Romulus's successor

.Modern historians dispute various points of this account. It is possible the original calendar was agriculturally based, observational of the seasons and stars rather the moon, with ten months of varying length filling the entire year. If this ever existed, it would have changed to the lunisolar system later credited to Numa during the kingdom or

It is clear that, for a variety of reasons, the intercalation necessary for the system's accuracy was not always observed. Astronomical events recorded in

Victorious in civil war, Caesar

At 365.25 days, the Julian calendar remained slightly longer than the solar year (365.24 days). By the 16th century, the date of Easter had shifted so far away from the vernal equinox that Pope Gregory XIII ordered a further correction to the calendar method, resulting in the establishment of the modern Gregorian calendar.

History

Prehistoric calendar

The original Roman

Against this,

Legendary 10-month calendar

The Romans themselves usually described their first organized year as one with ten fixed months,

Later Roman writers usually credited this calendar to

| English | Latin | Meaning | Length in days[17][18] |

|---|---|---|---|

| March | Mensis Martius | Month of Mars | 31 |

| April | Mensis Aprilis |

Month of Apru (Aphrodite)[29] | 30 |

| May | Mensis Maius |

Month of Maia[30]

|

31 |

| June | Mensis Iunius | Month of Juno | 30 |

| July | Mensis Quintilis Mensis Quinctilis[31] |

Fifth Month | 31 |

| August | Mensis Sextilis |

Sixth Month | 30 |

| September | Mensis September | Seventh Month | 30 |

| October | Mensis October | Eighth Month | 31 |

| November | Mensis November | Ninth Month | 30 |

| December | Mensis December | Tenth Month | 30 |

| Length of the year: | 304 | ||

Other traditions existed alongside this one, however. Plutarch's Parallel Lives recounts that Romulus's calendar had been solar but adhered to the general principle that the year should last for 360 days. Months were employed secondarily and haphazardly, with some counted as 20 days and others as 35 or more.[32][33] Plutarch records that while one tradition is that Numa added two new months to a ten-month calendar, another version is that January and February were originally the last two months of the year and Numa just moved them to the start of the year, so that January (named after a peaceful ruler called Janus) would come before March (which was named for Mars, the god of war).[34]

Rome's 8-day week, the

Republican calendar

The attested calendar of the

According to Livy, it was Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome (715–673 BC), who divided the year into twelve lunar months (History of Rome, I.19). Fifty days, says Censorinus, were added to the calendar and a day taken from each month of thirty days to provide for the two winter months: Januarius (January) and Februarius (February), both of which had 28 days (The Natal Day, XX). This was a lunar year of 354 days but, because of the Roman superstition about even numbers, an additional day was added to January to make the calendar 355 days long. Auspiciously, each month now had an odd number of days: Martius (March), Maius (May), Quinctilis (July), and October continued to have 31; the other months, 29, except for February, which had 28 days. Considered unlucky, it was devoted to rites of purification (februa) and expiation appropriate to the last month of the year. (Although these legendary beginnings attest to the venerability of the lunar calendar of the Roman Republic, its historical origin probably was the publication of a revised calendar by the Decemviri in 450 BC as part of the Twelve Tables, Rome's first code of law.) [4]

The inequality between the lunar year of 355 days and the

These Pythagorean-based changes to the Roman calendar were generally credited by the Romans to

According to Livy's

| English | Latin | Meaning | Length in days[45][46][32][33] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year (cmn.) |

2nd year (leap) |

3rd year (cmn.) |

4th year (leap) | ||||||||

| 1. | January | I. | Mensis Ianuarius

|

Month of Janus | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| 2. | February | II. | Mensis Februarius

|

Month of the Februa | 28 |

23 |

28 |

23 | |||

| Intercalary Month | Intercalaris Mensis (Mercedonius) | Month of Wages | 27 |

28 | |||||||

| 3. | March | III. | Mensis Martius | Month of Mars | 31 |

31 |

31 |

31 | |||

| 4. | April | IV. | Mensis Aprilis

|

Month of Aphrodite – from which the Etruscan Apru might have been derived | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| 5. | May | V. | Mensis Maius

|

Month of Maia | 31 |

31 |

31 |

31 | |||

| 6. | June | VI. | Mensis Iunius | Month of Juno | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| 7. | July | VII. | Mensis Quintilis

|

Fifth Month (from the earlier calendar starting in March) | 31 |

31 |

31 |

31 | |||

| 8. | August | VIII. | Mensis Sextilis

|

Sixth Month | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| 9. | September | IX. | Mensis September | Seventh Month | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| 10. | October | X. | Mensis October | Eighth Month | 31 |

31 |

31 |

31 | |||

| 11. | November | XI. | Mensis November | Ninth Month | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| 12. | December | XII. | Mensis December | Tenth Month | 29 |

29 |

29 |

29 | |||

| Whole year: | 355 | 377 | 355 | 378 | |||||||

According to the later writers Censorinus and Macrobius, to correct the mismatch of the correspondence between months and seasons due to the excess of one day of the Roman average year over the tropical year, the insertion of the intercalary month was modified according to the scheme: common year (355 days), leap year with 23-day February followed by 27-day Mercedonius (377 days), common year, leap year with 23-day February followed by 28-day Mercedonius (378 days), and so on for the first 16 years of a 24-year cycle. In the last 8 years, the intercalation took place with the month of Mercedonius only 27 days, except the last intercalation which did not happen. Hence, there would be a typical common year followed by a leap year of 377 days for the next 6 years and the remaining 2 years would sequentially be common years. The result of this twenty-four-year pattern was of great precision for the time: 365.25 days, as shown by the following calculation:

The consuls' terms of office were not always a modern calendar year, but ordinary consuls were elected or appointed annually. The traditional list of Roman consuls used by the Romans to date their years began in 509 BC.[47]

Flavian reform

Julian reform

Later reforms

After

In large part, this calendar continued unchanged under the

Days

Roman dates were

- Nones (Nonae or Non.), the 7th day of "full months"[55][f] and 5th day of hollow ones,[54] 8 days—"nine" by Roman reckoning—before the Ides in every month

- Ides (Idus, variously Eid. or Id.), the 15th day of "full months"[55][f] and the 13th day of hollow ones,[54] one day earlier than the middle of each month.

These are thought to reflect a prehistoric lunar calendar, with the kalends proclaimed after the sighting of the first sliver of the new crescent moon a day or two after the

The day before each was known as its eve (pridie); the day after each (postridie) was considered particularly unlucky.The days of the month were expressed in early Latin using the

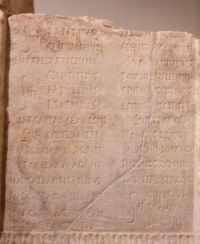

The kalends were the day for payment of debts and the account books (kalendaria) kept for them gave English its word calendar. The public Roman calendars were the fasti, which designated the religious and legal character of each month's days. The Romans marked each day of such calendars with the letters:[60]

- F (fastus, "permissible") on days when it was legal to initiate action in the courts of civil law (dies fasti, "allowed days")

- C (comitialis) on fasti days during which the Roman people could hold assemblies(dies comitiales)

- N (nefastus) on days when political and judicial activities were prohibited (dies nefasti)

- NP (uncertain)[g] on public holidays (feriae)

- QRCF (uncertain)rex sacrorum) could convene an assembly

- EN (endotercissus, an archaic form of intercissus, "halved") on days when most political and religious activities were prohibited in the morning and evening due to sacrifices being prepared or offered but were acceptable for a period in the middle of the day

Each day was also marked by a letter from A to H to indicate its place within the

Weeks

The

The

Months

The names of Roman months originally functioned as adjectives (e.g., the January kalends occur in the January month) before being treated as substantive nouns in their own right (e.g., the kalends of January occur in January). Some of their etymologies are well-established: January and March honor the gods

attempted to add themselves to the calendar after Augustus, but without enduring success.In classical Latin, the days of each month were usually reckoned as:[58]

| Days in month | 31d | 31d | 30d | 29d | 28d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Months before Julian reform |

Mar May Jul Oct |

Jan Apr Jun Aug Sep Nov Dec |

Feb | ||||

Months after Julian reform |

Mar May Jul Oct |

Jan Aug Dec |

Apr Jun Sep Nov |

(Feb) | Feb | ||

| Day name in English | Day name in Latin | Abbr | [f][i] | [j] | [k] | [l] | [m] |

| On the Kalends | Kalendis | Kal. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| The day after the Kalends | postridie Kalendas | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| The 6th day before the Nones | ante diem sextum Nonas | a.d. VI Non. | 2 | ||||

| The 5th day before the Nones | ante diem quintum Nonas | a.d. V Non. | 3 | ||||

| The 4th day before the Nones | ante diem quartum Nonas | a.d. IV Non. | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| The 3rd day before the Nones | ante diem tertium Nonas | a.d. III Non. | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| On the day before the Nones | Pridie Nonas | Prid. Non. | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| On the Nones | Nonis | Non. | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| The day after the Nones | postridie Nonas | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| The 8th day before the Ides | ante diem octavum Idus | a.d. VIII Eid. | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| The 7th day before the Ides | ante diem septimum Idus | a.d. VII Eid. | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| The 6th day before the Ides | ante diem sextum Idus | a.d. VI Eid. | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| The 5th day before the Ides | ante diem quintum Idus | a.d. V Eid. | 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| The 4th day before the Ides | ante diem quartum Idus | a.d. IV Eid. | 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| The 3rd day before the Ides | ante diem tertium Idus | a.d. III Eid. | 13 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| On the day before the Ides | Pridie Idus | Prid. Eid. | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| On the Ides | Idibus | Eid. | 15 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| The day after the Ides | postridie Idus | 16 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | |

| The 19th day before the Kalends | ante diem undevicesimum Kalendas | a.d. XIX Kal. | 14 | ||||

| The 18th day before the Kalends | ante diem duodevicesimum Kalendas | a.d. XVIII Kal. | 15 | 14 | |||

| The 17th day before the Kalends | ante diem septimum decimum Kalendas | a.d. XVII Kal. | 16 | 16 | 15 | 14 | |

| The 16th day before the Kalends | ante diem sextum decimum Kalendas | a.d. XVI Kal. | 17 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 |

| The 15th day before the Kalends | ante diem quintum decimum Kalendas | a.d. XV Kal. | 18 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 |

| The 14th day before the Kalends | ante diem quartum decimum Kalendas | a.d. XIV Kal. | 19 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 |

| The 13th day before the Kalends | ante diem tertium decimum Kalendas | a.d. XIII Kal. | 20 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 |

| The 12th day before the Kalends | ante diem duodecimum Kalendas | a.d. XII Kal. | 21 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 18 |

| The 11th day before the Kalends | ante diem undecimum Kalendas | a.d. XI Kal. | 22 | 22 | 21 | 20 | 19 |

| The 10th day before the Kalends | ante diem decimum Kalendas | a.d. X Kal. | 23 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| The 9th day before the Kalends | ante diem nonum Kalendas | a.d. IX Kal. | 24 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 |

| The 8th day before the Kalends | ante diem octavum Kalendas | a.d. VIII Kal. | 25 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 22 |

| The 7th day before the Kalends | ante diem septimum Kalendas | a.d. VII Kal. | 26 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 23 |

| The 6th day before the Kalends | ante diem sextum Kalendas | a.d. VI Kal. | 27 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 24[n] |

| The 5th day before the Kalends | ante diem quintum Kalendas | a.d. V Kal. | 28 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 |

| The 4th day before the Kalends | ante diem quartum Kalendas | a.d. IV Kal. | 29 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 |

| The 3rd day before the Kalends | ante diem tertium Kalendas | a.d. III Kal. | 30 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 |

| On the day before the Kalends | Pridie Kalendas | Prid. Kal. | 31 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 28 |

Dates after the ides count forward to the kalends of the next month and are expressed as such. For example, March 19 was expressed as "the 14th day before the April Kalends" (a.d. XIV Kal. Apr.), without a mention of March itself. The day after a kalends, nones, or ides was also often expressed as the "day after" (postridie) owing to their special status as particularly unlucky "black days".

The anomalous status of the new 31-day months under the Julian calendar was an effect of Caesar's desire to avoid affecting the festivals tied to the nones and ides of various months. However, because the dates at the ends of the month all counted forward to the next kalends, they were all shifted by one or two days by the change. This created confusion with regard to certain anniversaries. For instance, Augustus's birthday on the 23rd day of September was a.d. VIII Kal. Oct. in the old calendar but a.d. IX Kal. Oct. under the new system. The ambiguity caused honorary festivals to be held on either or both dates.

Intercalation

The Republican calendar only had 355 days, which meant that it would quickly unsynchronize from the solar year, causing, for example, agricultural festivals to occur out of season. The Roman solution to this problem was to periodically lengthen the calendar by adding extra days within February. February was broken into two parts, each with an odd number of days. The first part ended with the Terminalia on the 23rd (a.d. VII Kal. Mart.), which was considered the end of the religious year; the five remaining days beginning with the Regifugium on the 24th (a.d. VI Kal. Mart.) formed the second part; and the intercalary month Mercedonius was inserted between them. In such years, the days between the ides and the Regifugium were counted down to either the Intercalary Kalends or to the Terminalia. The intercalary month counted down to nones and ides on its 5th and 13th day in the manner of the other short months. The remaining days of the month counted down towards the March Kalends, so that the end of Mercedonius and the second part of February were indistinguishable to the Romans, one ending on a.d. VII Kal. Mart. and the other picking up at a.d. VI Kal. Mart. and bearing the normal festivals of such dates.

Apparently because of the confusion of these changes or uncertainty as to whether an intercalary month would be ordered, dates after the February ides are attested as sometimes counting down towards the

rather than the intercalary or March kalends.The third-century writer Censorinus says:

When it was thought necessary to add (every two years) an intercalary month of 22 or 23 days, so that the civil year should correspond to the natural (solar) year, this intercalation was in preference made in February, between the Terminalia [23rd] and Regifugium [24th].[77]

The fifth-century writer Macrobius says that the Romans intercalated 22 and 23 days in alternate years;[78] the intercalation was placed after February 23 and the remaining five days of February followed.[79] To avoid the nones falling on a nundine, where necessary an intercalary day was inserted "in the middle of the Terminalia, where they placed the intercalary month".[80] This appears to have been generally correct. In 170 BC, Intercalaris began on the second day after February 23[81] and, in 167 BC, it began on the day after February 23.[82]

There is another theory which says that in intercalary years February had 23 or 24 days and Intercalaris had 27. No date is offered for the Regifugium in 378-day years.[84] Macrobius describes a further refinement whereby, in one 8-year period within a 24-year cycle, there were only three intercalary years, each of 377 days. This refinement brings the calendar back in line with the seasons and averages the length of the year to 365.25 days over 24 years.

The Pontifex Maximus determined when an intercalary month was to be inserted. On average, this happened in alternate years. The system of aligning the year through intercalary months broke down at least twice: the first time was during and after the

Although there are many stories to interpret the intercalation, a period of 22 or 23 days is always 1⁄4 synodic month short. Obviously, the month beginning shifts forward (from the new moon, to the third quarter, to the full moon, to the first quarter, back the new moon) after intercalation.

Years

As mentioned above, Rome's legendary 10-month calendar notionally lasted for 304 days but was usually thought to make up the rest of the

The

The Romans did not have records of their early calendars but, like modern historians, assumed the year originally began in March on the basis of the names of the months following June. The consul

In addition to

Conversion to Julian or Gregorian dates

The continuity of names from the Roman to the

Given the paucity of records regarding the state of the calendar and its intercalation, historians have reconstructed the correspondence of Roman dates to their Julian and Gregorian equivalents from disparate sources. There are detailed accounts of the decades leading up to the Julian reform, particularly the speeches and letters of

See also

- List of calendars

- Alexandrian, Byzantine, & Gregorian calendars

- Calendar of 354

- List of Roman consuls and ab urbe condita dating

- General Roman Calendar of the Catholic Church

- Roman festivals

- Undecimber

Notes

- ancient Greek calendars; and the Gregorian calendar, which refined the Julian system to bring it into still closer alignment with the tropical year.

- ^ Two days in a row were given the same date. This practice continued well into the sixteenth century.

- ^ Plutarch reports this tradition while claiming that the months had more probably predated or originated with Romulus.[32][33]

- ^ This equivalence was first described by Stanyan in his history of ancient Greece.[40]

- ^ There are some documents which state the month had been renamed as early as 26 or 23 BC, but the date of the Lex Pacuvia is certain.

- ^ a b c The original 31-day months of the Roman calendar were March, May, Quintilis or July, and October.

- ^ The NP days are sometimes thought to mark days when political and judicial activities were prohibited only until noon, standing for nefastus priore.

- ^ The QRCF days are sometimes supposed, on the basis of the Fasti Viae Lanza which gives it as Q. Rex C. F., to stand for "Permissible when the King Has Entered the Comitium" (Quando Rex Comitiavit Fas).[61]

- ^ The 31-day months of prior to the Julian reform, March, May, Quintilis (July), and October, continued using the old system with their Nones on the 9th and Ides on the 15th.

- ^ The 31-day months established by the Julian reform, January, Sextilis (August), and December, used a new system with their Nones on the 7th and Ides on the 13th.

- ^ The 30-day months established by the Julian reform were April, June, September, and November.

- ^ In leap years late in the imperial period, February was reckoned as a 29 day month with all days lasting 24 hours.

- ^ In leap years early period after the Julian reform, February had 29 days but was reckoned as a 28 day month by treating the sixth day before the March Kalends as lasting for 48 hours.

- ^ After the Julian reform until late in the imperial period, this day was reckoned to last 48 hours during a leap year.

References

Citations

- ^ Enc. Brit. (1911), p. 193.

- ^ Mommsen & al. (1864), p. 216.

- ^ Michels (1949), pp. 323–324.

- ^ a b c d e Grout (2023).

- ^ a b c d e f g Mommsen & al. (1864), p. 218.

- ^ a b c Michels (1949), p. 330.

- The Natal Day, Ch. XXII.

- On Agriculture.

- Farming.

- Vergil, Georgics.

- On Farming.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History.

- On Farming.

- ^ Wissowa (1896).

- ^ Michels (1949), p. 322.

- ^ a b Michels (1949), p. 331.

- ^ a b c d Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 12, §3.

- ^ a b Kaster (2011), p. 137.

- ^ Mommsen & al. (1864), p. 217.

- ^ Censorinus, Macrobius, and Solinus, cited in Key (1875)

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 12, §39.

- ^ Kaster (2011), p. 155.

- ^ The Natal Day, Ch. XX.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 13, §20.

- ^ Kaster (2011), p. 165.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 12, §§5 & 38.

- ^ Kaster (2011), pp. 137 & 155.

- ^ a b Rüpke (2011), p. 23.

- ^ "April". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Randomhouse Inc. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ "May". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Randomhouse Inc. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ Blackburn & al. (1999), p. 669.

- ^ a b c d e Plutarch, Life of Numa section XVIII.

- ^ a b c d e Perrin (1914), pp. 368 ff.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Numa section XIX

- ^ Rüpke (2011), p. 40

- ^ Mommsen & al. (1864), p. 219.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 12, §34.

- ^ Kaster (2011), p. 153.

- ^ Roberts (1905), Book I, Ch. 19, §6.

- ^ Stanyan (1707), p. 330.

- ^ 47.13 and 47.14: "[47.13] In the five hundred and ninety-eighth year after the founding of the city, the consuls began to enter upon their office on 1 January. [47.14] The cause of this change in the date of the elections was a rebellion in Hispania."

- ^ Ovid, Book II.

- ^ Kline (2004), Book II, Introduction.

- ^ Fowler (1899), p. 5.

- ^ Macrobius.

- ^ a b c Kaster (2011).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mathieson (2003), p. 14.

- ^ Michels (1949), p. 340.

- ^ Lanfranchi (2013).

- ^ Pliny, Book XVIII, Ch. 211.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 14, §2.

- ^ Rotondi (1912), p. 441.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 12.

- ^ a b c d Beck (1838), p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e Beck (1838), p. 176.

- ^ Ovid, Book I, ll. 55–56.

- ^ Kline (2004), Book I, Introduction.

- ^ a b Beck (1838), p. 177.

- ^ Smyth (1920), §§1582–1587.

- ^ Scullard (1981), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Rüpke (2011), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Brind'Amour (1983), pp. 256–275.

- ^ "January, n.", OED.

- ^ "March, n.2", OED.

- ^ "July, n.", OED.

- ^ "August, n.", OED.

- ^ "†quintile, n.2", OED.

- ^ "sextile, adj. and n.", OED.

- ^ a b "September, n.", OED.

- ^ "October, n.", OED.

- ^ "November, n.", OED.

- ^ "December, n.", OED.

- ^ "February, n.", OED.

- ^ "May, n.2", OED.

- ^ "June, n.", OED.

- which?]

- ^ Censorinus, The Natal Day, 20.28, tr. William Maude, New York 1900, available at [1].

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 13, §12.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 13, §15.

- ^ Macrobius, Book I, Ch. 13, §16, 19.

- ^ Livy, Book XLIII, Ch. 11, §13.

- ^ Livy, Book XLV, Ch. 44, §3.

- ^ a b Varro, On the Latin language, 6.13, tr. Roland Kent, London 1938, available at [2].

- ^ Michels (1967).

- ^ Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum I, CIL VI.

- ^ a b Mathieson (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Roberts (1905), Book XLVII.

- ^ Roberts (1905).

Bibliography

- "Fasti", Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. X, New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911, pp. 192–193.

- Beck, Charles (1838), "Of the Roman Calendar", Latin Syntax, Chiefly from the German of C.G. Zumpt, Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown.

- Blackburn, Bonnie; et al. (1999), The Oxford Companion to the Year, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brind'Amour, P. (1983), Le Calendrier Romain: Recherches Chronologiques (in French), Ottawa

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - De Agri Culture(in Latin).

- Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- De Die Natali(in Latin).

- Censorinus (1900), De Die Natali ("The Natal Day"), translated by Maude, William, New York: Cambridge Encyclopedia Press.

- De Re Rustica(in Latin).

- Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (1745), Of Husbandry in Twelve Books and His Book Concerning Trees..., London: Andrew Millar, anonymous translation.

- Fowler, W. Warde(1899), The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic, New York: Macmillan & Co.

- Grout, James (2023), "The Roman Calendar", Encyclopaedia Romana, Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Key, Thomas Hewitt (1875), "Calendarium", A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, London: John Murray, pp. 223–233.

- Lanfranchi, Thibaud (October 3, 2013), "À Propos de la Carrière de Cn. Flavius", Mélanges de l'École Française de Rome: Antiquité, vol. 125, . (in French)

- Ab Urbe Condita(in Latin).

- Titus Livius (1905), The History of Rome, Everyman's Library, vol. I, translated by Roberts, Canon; et al., London: J.M. Dent & Sons, archived from the original on April 29, 2017.

- Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, Saturnalia (in Latin).

- ISBN 9780674996496.

- Mathieson, Ralph W. (2003), People, Personal Expression, and Social Relations in Late Antiquity, Vol. II, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Michels, Agnes Kirsopp Lake (1949), "The 'Calendar of Numa' and the Pre-Julian Calendar", Transactions & Proceedings of the APA, vol. 80, Philadelphia: American Philological Association, pp. 320–346.

- ISBN 9781400849789).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Mommsen, Theodor (1864), Dickson, William Purdie (ed.), The History of Rome, Vol. I: The Period Anterior to the Abolition of the Monarchy, London: Richard Bentley. [ 1 ]

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Fastorum Libri VI (in Latin).

- Publius Ovidius Naso (2004), On the Roman Calendar, translated by Kline, Anthony S., Poetry in Translation.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- De Re Rustica(in Latin).

- Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius (1807), The Fourteen Books of Palladius Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus on Agriculture, translated by Owen, Thomas, London: J. White.

- Historia Naturalis(in Latin).

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (1855), The Natural History, translated by Bostock, John; et al., London: Taylor & Francis.

- Plutarch, Βίοι Παράλληλοι [Parallel Lives] (in Ancient Greek).

- Plutarch (1914), "The Life of Numa", The Parallel Lives, Vol. I, Loeb Classical Library, translated by Perrin, Bernadotte, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Rotondi, Giovanni (1912), Leges Publicae Populi Romani (in Latin), Milan: Società Editrice Libraria.

- ISBN 978-0-470-65508-5.

- Scullard, Howard Hayes (1981), Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920), A Greek Grammar for Colleges, New York: American Book Co..

- Stanyan, Temple (1707), Grecian History, London: J. & R. Tonson.

- Wissowa, Georg Otto August (1896), "Augures", Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, vol. II, Part 2, translated by Stokes, Felix, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzlersche Buchhandlung, pp. 2313–2344.

- Rerum Rusticarum Libri III(in Latin).

- Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Publius Vergilius Maro, Georgica (in Latin).

- Publius Vergilius Maro (1910), The Eclogues and Georgics of Virgil, translated by Mackail, John William, London: Longmans, Green, & Co.

External links

- Chris Bennett's reconstruction of early Roman dates in terms of the Julian calendar

- Early Roman Calendar – History

- Roman Date Calculator The North American Institute of Living Latin Studies

- "Theological commentary on the daily Gospel Reading". Apostolic Movement (Roman Catholic Church) (in English, French, and Spanish).