Romanian War of Independence

| Romanian War of Independence (1877–1878) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 | |||||||||

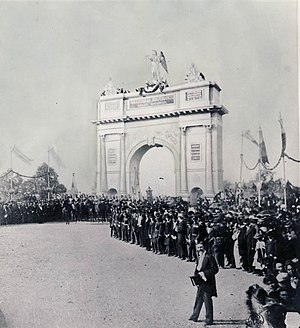

Romanian troops returning to Bucharest after the war, 8 October 1878. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

190 cannons 500 cannons[2] |

210 cannons | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

30,000 killed in battle, 50,000 died from wounds and diseases[5] (during the entire Russo-Turkish War)[6] 2 river monitors sunk[7][8] | ||||||||

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

The Romanian War of Independence is the name used in Romanian historiography to refer to the

Romanian proclamation of independence

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2016) |

On May 21 [O.S. May 9] 1877, in the Romanian parliament, Mihail Kogălniceanu read the act of independence of Romania as the will of the Romanian people. A day later, on May 22 [O.S. May 10] 1877, the act was signed by Prince Carol I. For symbolic reasons, the date of May 10 was celebrated as Independence Day, until 1947, since it also marked the celebration of the day when the German Prince Carol first came to Bucharest (May 10, 1866). After the Declaration, the Romanian government immediately cancelled paying tribute to the Ottoman Empire (914,000 lei), and the sum was given instead to the Romanian War Ministry.

Initially, before 1877, Russia did not wish to cooperate with Romania, since they did not wish Romania to participate in the peace treaties after the war, but the Russians encountered a very strong Ottoman army of 40,000 soldiers, led by Osman Pasha, at the Siege of Plevna (Pleven) where the Russian troops, led by Russian generals, suffered very heavy losses and were routed in several battles.[10]

Conflict

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2016) |

Due to great losses,

Prince Carol I accepted the Duke's proposal to become the Marshal of the Russian troops in addition to the command of his own Romanian army, thus being able to lead the combined armed forces to the conquest of Plevna and the formal surrender, after heavy fighting, of the Turkish General Osman Pasha. The Army won the battles of Grivitsa and Rahova, and on 28 November 1877 the Plevna citadel capitulated, and Osman Pasha surrendered the city, the garrison and his sword to the Romanian colonel Mihail Cerchez and Russian division commander Ivan Ganetsky. After the occupation of Plevna, the Romanian Army returned to the Danube and won the battles of Vidin and Smârdan.

On 19 January 1878, the Ottoman Empire requested an armistice, which was accepted by Russia and Romania. Romania won the war but at a cost of about 10,000 casualties. Additionally, another 19,084 soldiers fell sick during the campaign.

The Romanian Navy consisted of three gunboats: Ştefan cel Mare, România and Fulgerul and one spar torpedo boat, Rândunica.[14] The three gunboats displaced 352, 130 and 85 tons respectively.[15] Ştefan cel Mare and România were each armed with four guns and Fulgerul with one gun.[16] Despite its inferiority on paper, the Romanian Navy destroyed many Turkish river gunboats.[17]

According to the Russian-Romanian treaty signed in April that year, the Romanian spar torpedo boat Rândunica served under joint Romanian-Russian command. She was also known as Tsarevich by the Russians. Her crew consisted of two Russian Lieutenants, Dubasov and Shestakov, and three Romanians: Major Murgescu (the official liaison officer with the Russian headquarters), an engine mechanic and a navigator. The attack of Rândunica took place during the night of 25–26 May 1877, near Măcin. As she was approaching the Ottoman monitor Seyfi, the latter fired three rounds at her without any effect. Before she could fire the fourth round, Rândunica's spar struck her between the midships and the stern. A powerful explosion followed, with debris from the Ottoman warship rising up to 40 meters in the air. The half-sunk monitor then re-opened fire, but was struck once again, with the same devastating effects. The crew of Seyfi subsequently fired their rifles at Rândunica, as the latter was retreating and their monitor was sinking. Following this action, Ottoman warships throughout the remainder of the war would always retreat upon sighting spar torpedo boats. The Russian Lieutenants Dubasov and Shestakov were decorated with the Order of St. George, while Major Murgescu was decorated with the Order of Saint Vladimir as well as the Order of the Star of Romania. Rândunica was returned to full Romanian control in 1878, after the Russian ground forces had finished crossing the Danube.[18][19] The Ottoman monitor Seyfi was a 400-ton ironclad warship, with a maximum armor thickness of 76 mm and armed with two 120 mm guns.

Another Ottoman monitor, the Podgoriçe, was shelled and sunk by Romanian coastal artillery on 7 November 1877.[8]

Aftermath

The

The Convention between Russia and Romania, which established the transit of Russian troops through the country, is one by which Russia obliged itself "to maintain and have the political rights of Romanian state observed, such as they result from the internal laws and the existent tratatives and also to defend the present integrity of Romania".

The treaty was not recognised by the

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b Istoria Militară a Poporului Român (The Military History of the Romanian People), Centrul de Studii și Cercetări de Istorie și Teorie Militară, Editura Militară, București, 1987 (in Romanian)

- ^ Мерников А. Г., Спектор А. А. Всемирная история войн. — Минск: 2005. — С. 376.

- ^ Scafes, Cornel, et al., Armata Romania in Razvoiul de Independenta 1877–1878 (The Romanian Army in the War of Independence 1877–1878). Bucuresti, Editura Sigma, 2002, p. 149 (Romence)

- ^ Урланис Б. Ц. Войны и народонаселение Европы. — М.: 1960.

- ISBN 985-13-2607-0.

- ^ Kaminskii, L. S., și Novoselskii, S. A., Poteri v proșlîh voinah (Victimele războaielor trecute). Medgiz, Moscova, 1947, pp. 36, 37

- ^ Cristian Crăciunoiu, Romanian Navy Torpedo Boats, p. 19

- ^ a b Nicolae Petrescu, M. Drăghiescu, Istoricul principalelor puncte pe Dunăre de la gura Tisei până la Mare şi pe coastele mării de la Varna la Odessa, p. 160 (in Romanian)

- ^ "Demersuri româno-ruse privind implicarea armatei române la sud de Dunăre". Archived from the original on 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ^ a b https://archive.org/stream/reminiscencesofk00kremiala "Reminiscences of the KING OF ROMANIA", Edited from the original with an Introduction by Sidney Whitman, Authorized edition, Harper& Brothers: New York and London, 1899

- Jiu and Corabiathis demonstration is absolutely necessary to facilitate my movements.)

- ^ Dan Falcan (March 2022). "Războiul din 1877-1878, independența României și Marile Puteri". Historia (in Romanian). No. 38. pp. 10−11.

- ^ Manuel Stănescu (7 June 2017). "9 mai 1877: România independentă". historia.ro (in Romanian).

- ^ Cristian Crăciunoiu, Romanian Navy Torpedo Boats, p. 13

- ^ Constantin Olteanu, The Romanian armed power concept: a historical approach, p. 152

- ^ W. S. Cooke, The Ottoman Empire and its Tributary States, p. 117

- ^ Béla K. Kiraly, Gunther Erich Rothenberg, War and Society in East Central Europe: Insurrections, Wars, and the Eastern Crisis in the 1870s, p. 104

- ^ Mihai Georgescu, Warship International, 1987: The Romanian Navy's Torpedo Boat Rindunica

- ^ Cristian Crăciunoiu, Romanian navy torpedo boats, Modelism, 2003, pp. 13-18

- ^ "Treaty of San Stefano | Russia-Turkey [1878] | Britannica".

- ^ Istoria Romanilor de la Carol I la Nicolae Ceausescu By Ioan Scurtu, pp 132

- ^ Babcock, Alex (30 June 2017). "Russian Mediterranean Sea Interest Before World War I". Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (2016). The Roots and Consequences of 20th-Century Warfare. California: ABC-CLIO. p. 1.

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/reminiscencesofk00kremiala "Reminiscences of the KING OF ROMANIA", Edited from the original with an Introduction by Sidney Whitman, Authorized edition, Harper& Brothers: New York and London, 1899, pp.15–20.

External links

- The Plevna Delay Archived 2015-11-13 at the Wayback Machine by Richard T. Trenk Sr. (Originally published in Man At Arms magazine, Number Four, August, 1997)

- The Romanian Army of the Russo-Turkish War 1877–78

- Grivitsa Romanian Mausoleum in Bulgaria

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 931–936.