Sino-Roman relations

c. 1st century BCE - 1453

Sino-Roman relations comprised the (primarily indirect) contacts and flows of trade goods, information, and occasional travelers between the

The indirect exchange of goods on land along the

In

Geographical accounts and cartography

Roman geography

Beginning in the 1st century BC with Virgil, Horace, and Strabo, Roman historians offer only vague accounts of China and the silk-producing Seres people of the Far East, who were perhaps the ancient Chinese.[2][3] The 1st-century AD geographer Pomponius Mela asserted that the lands of the Seres formed the centre of the coast of an eastern ocean, flanked to the south by India and to the north by the Scythians of the Eurasian Steppe.[2] The 2nd-century AD Roman historian Florus seems to have confused the Seres with peoples of India, or at least noted that their skin complexions proved that they both lived "beneath another sky" than the Romans.[2] Roman authors generally seem to have been confused about where the Seres were located, in either Central Asia or East Asia.[4] The historian Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330 – c. 400 AD) wrote that the land of the Seres was enclosed by "lofty walls" around a river called Bautis, possibly a description of the Yellow River.[2]

The existence of China was known to

Classical geographers such as

From

Chinese geography

Detailed geographical information about the Roman Empire, at least its easternmost territories, is provided in traditional Chinese historiography. The Shiji by Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BC) gives descriptions of countries in Central Asia and West Asia. These accounts became significantly more nuanced in the Book of Han, co-authored by Ban Gu and his sister Ban Zhao, younger siblings of the general Ban Chao, who led military exploits into Central Asia before returning to China in 102 AD.[29] The westernmost territories of Asia as described in the Book of the Later Han compiled by Fan Ye (398–445 AD) formed the basis for almost all later accounts of Daqin.[29][note 1] These accounts seem to be restricted to descriptions of the Levant, particularly Syria.[29]

Historical linguist Edwin G. Pulleyblank explains that Chinese historians considered Daqin to be a kind of "counter-China" located at the opposite end of their known world.[30][31] According to Pulleyblank, "the Chinese conception of Dà Qín was confused from the outset with ancient mythological notions about the far west".[32][31] From the Chinese point of view, the Roman Empire was considered "a distant and therefore mystical country," according to Krisztina Hoppál.[33] The Chinese histories explicitly related Daqin and Lijian (also "Li-kan", or Syria) as belonging to the same country; according to Yule, D. D. Leslie, and K. H. G. Gardiner, the earliest descriptions of Lijian in the Shiji distinguished it as the Hellenistic-era Seleucid Empire.[34][35][36] Pulleyblank provides some linguistic analysis to dispute their proposal, arguing that Tiaozhi (條支) in the Shiji was most likely the Seleucid Empire and that Lijian, although still poorly understood, could be identified with either Hyrcania in Iran or even Alexandria in Egypt.[37]

The

The

Embassies and travel

Prelude

Some contact may have occurred between

Embassy to Augustus

The historian Florus described the visit of numerous envoys, including the "

Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus even Scythians and Sarmatians sent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, the Seres came likewise, and the Indians who dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours.[54][55]

In the entire corpus of

Envoy Gan Ying

The

In 97 AD, Ban Chao sent an envoy named Gan Ying to explore the far west. Gan made his way from the Tarim Basin to Parthia and reached the Persian Gulf.[60] Gan left a detailed account of western countries; he apparently reached as far as Mesopotamia, then under the control of the Parthian Empire. He intended to sail to the Roman Empire, but was discouraged when told that the trip was dangerous and could take two years.[61][62] Deterred, he returned to China bringing much new information on the countries to the west of Chinese-controlled territories,[63] as far as the Mediterranean Basin.[60]

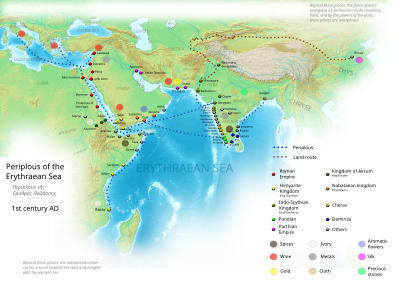

Gan Ying is thought to have left an account of the Roman Empire (Daqin in Chinese) that relied on secondary sources, most likely from sailors in the ports which he visited. The Book of the Later Han locates it in Haixi ("west of the sea", or Roman Egypt;[29][64] the sea is the one known to the Greeks and Romans as the Erythraean Sea, which included the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and Red Sea):[65]

Its territory extends for several thousands of li [a li during the Han dynasty equalled 415.8 metres].[66] They have established postal relays at intervals, which are all plastered and whitewashed. There are pines and cypresses, as well as trees and plants of all kinds. It has more than four hundred walled towns. There are several tens of smaller dependent kingdoms. The walls of the towns are made of stone.[67]

The Book of the Later Han gives a positive, if inaccurate, view of Roman governance:

Their kings are not permanent rulers, but they appoint men of merit. When a severe calamity visits the country, or untimely rain-storms, the king is deposed and replaced by another. The one relieved from his duties submits to his degradation without a murmur. The inhabitants of that country are tall and well-proportioned, somewhat like the Han [Chinese], whence they are called [Daqin].[68]

Yule noted that although the description of the Roman Constitution and products was garbled, the Book of the Later Han offered an accurate depiction of the coral fisheries in the Mediterranean.[69] Coral was a highly valued luxury item in Han China, imported among other items from India (mostly overland and perhaps also by sea), the latter region being where the Romans sold coral and obtained pearls.[70] The original list of Roman products given in the Book of the Later Han, such as sea silk, glass, amber, cinnabar, and asbestos cloth, is expanded in the Weilüe.[38][71] The Weilüe also claimed that in 134 AD the ruler of the Shule Kingdom (Kashgar), who had been a hostage at the court of the Kushan Empire, offered blue (or green) gems originating from Haixi as gifts to the Eastern Han court.[38] Fan Ye, the editor of the Book of the Later Han, wrote that former generations of Chinese had never reached these far western regions, but that the report of Gan Ying revealed to the Chinese their lands, customs and products.[72] The Book of the Later Han also asserts that the Parthians (Chinese: 安息; Anxi) wished "to control the trade in multi-coloured Chinese silks" and therefore intentionally blocked the Romans from reaching China.[64]

Possible Roman Greeks in Burma and China

It is possible that a group of Greek acrobatic performers, who claimed to be from a place "west of the seas" (Roman Egypt, which the Book of the Later Han related to the Daqin empire), were presented

First Roman embassy

The first group of people claiming to be an ambassadorial mission of Romans to China was recorded as having arrived in 166 AD by the Book of the Later Han. The embassy came to

"... 其王常欲通使於漢,而安息欲以漢繒彩與之交市,故遮閡不得自達。至桓帝延熹九年,大秦王安敦遣使自日南徼外獻象牙、犀角、瑇瑁,始乃一通焉。其所表貢,並無珍異,疑傳者過焉。"

"... The king of this state always wanted to enter into diplomatic relations with the Han. ButHou Hanshu (ch. 88)[83]

As Antoninus Pius died in 161 AD, leaving the empire to his adoptive son Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, and the envoy arrived in 166 AD,

Other Roman embassies

The

Yule mentions that in the early 3rd century AD a ruler of Daqin sent an envoy with gifts to the northern Chinese court of Cao Wei (220–266 AD) that included glassware of various colours.[92] Several years later a Daqin craftsman is mentioned as showing the Chinese how to make "flints into crystal by means of fire", a curiosity to the Chinese.[92]

Another embassy from Daqin is recorded as bringing tributary gifts to the Chinese

Fulin: Eastern Roman embassies

Chinese histories for the

Yule asserts that the additional Fulin embassies during the Tang period arrived in 711 and 719 AD, with another in 742 AD that may have been Nestorian monks.

The 719 AD a Fulin embassy ostensibly came from

The last diplomatic contacts with Fulin are recorded as having taken place in the 11th century AD. From the Wenxian Tongkao, written by historian

The

Within the

During the sixth year of Yuan-yu [1091] they sent two embassies, and their king was presented, by Imperial order, with 200 pieces of cloth, pairs of silver vases, and clothing with gold bound in a girdle. According to the historians of the T'ang dynasty, the country of Fulin was held to be identical with the ancient Ta-ts'in. It should be remarked, however, that, although Ta-ts'in has from the Later Han dynasty when Zhongguo was first communicated with, till down to the Chin and T'ang dynasties has offered tribute without interruption, yet the historians of the "four reigns" of the Sung dynasty, in their notices of Fulin, hold that this country has not sent tribute to court up to the time of Yuan-feng [1078–1086] when they sent their first embassy offering local produce. If we, now, hold together the two accounts of Fulin as transmitted by the two different historians, we find that, in the account of the T'ang dynasty, this country is said "to border on the great sea in the west"; whereas the Sung account says that "in the west you have still thirty days' journey to the sea;" and the remaining boundaries do also not tally in the two accounts; nor do the products and the customs of the people. I suspect that we have before us merely an accidental similarity of the name, and that the country is indeed not identical with Ta-ts'in. I have, for this reason, appended the Fulin account of the T'ang dynasty to my chapter on Ta-ts'in, and represented this Fulin of the Sung dynasty as a separate country altogether.[123]

The

Trade relations

Roman exports to China

Direct trade links between the Mediterranean lands and India had been established in the late 2nd century BC by the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt.[127] Greek navigators learned to use the regular pattern of the monsoon winds for their trade voyages in the Indian Ocean. The lively sea trade in Roman times is confirmed by the excavation of large deposits of Roman coins along much of the coast of India. Many trading ports with links to Roman communities have been identified in India and Sri Lanka along the route used by the Roman mission.[128] Archaeological evidence stretching from the Red Sea ports of Roman Egypt to India suggests that Roman commercial activity in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia declined heavily with the Antonine Plague of 166 AD, the same year as the first Roman embassy to Han China, where similar plague outbreaks had occurred from 151 AD.[129][130]

High-quality

From Chinese sources it is known that other Roman luxury items were esteemed by the Chinese. These include gold-embroidered

A maritime route opened up with the Chinese-controlled port of

The trade connection from Cattigara extended, via ports on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, all the way to Roman-controlled ports in

Chinese silk in the Roman Empire

During the 1st century BC silk was still a rare commodity in the Roman world; by the 1st century AD this valuable trade item became much more widely available.

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes ... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body.

— Seneca the Elder c. 3 BC – 65 AD, Excerpta Controversiae 2.7[153]

Trade items such as spice and silk had to be paid for with Roman gold coinage. There was some demand in China for Roman glass; the Han Chinese also produced glass in certain locations.[154][149] Chinese-produced glassware date back to the Western Han era (202 BC – 9 AD).[155] In dealing with foreign states such as the Parthian Empire, the Han Chinese were perhaps more concerned with diplomatically outmaneuvering their chief enemies, the nomadic Xiongnu, than with establishing trade, since mercantile pursuits and the merchant class were frowned upon by the gentry who dominated the Han government.[156]

Roman and Byzantine currency discovered in China

Shortly after the

The earliest gold

Even with the Byzantine production of silk starting in the 6th century AD, Chinese varieties were still considered to be of higher quality.

Human remains

In 2010,

A 2016 analysis of archaeological finds from Southwark in London, the site of the ancient Roman city Londinium in Roman Britain, suggests that two or three skeletons from a sample of twenty-two dating to the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD are of Asian ancestry, and possibly of Chinese descent. The assertion is based on forensics and the analysis of skeletal facial features. The discovery has been presented by Dr Rebecca Redfern, curator of human osteology at the Museum of London.[172][173] No DNA analysis has yet been done, the skull and tooth samples available offer only fragmentary pieces of evidence, and the samples that were used were compared with the morphology of modern populations, not ancient ones.[174]

Hypothetical military contact

The historian Homer H. Dubs speculated in 1941 that Roman prisoners of war who were transferred to the eastern border of the Parthian Empire might later have clashed with Han troops there.[175]

After a Roman army under the command of

There have been attempts to promote the Sino-Roman connection for tourism, but Dubs' synthesis of Roman and Chinese sources has not found acceptance among historians, on the grounds that it is highly speculative and reaches too many conclusions without sufficient hard evidence.[178][179] DNA testing in 2005 confirmed the Indo-European ancestry of a few inhabitants of modern Liqian; this could be explained by transethnic marriages with Indo-European people known to have lived in Gansu in ancient times,[180][181] such as the Yuezhi and Wusun. A much more comprehensive DNA analysis of more than two hundred male residents of the village in 2007 showed close genetic relation to the Han Chinese populace and great deviation from the Western Eurasian gene pool.[182] The researchers conclude that the people of Liqian are probably of Han Chinese origin.[182] The area lacks archaeological evidence of a Roman presence, such as coins, pottery, weaponry, architecture, etc.[180][181]

See also

- China–Greece relations

- China–Italy relations

- China–European Union relations

- Comparative studies of the Roman and Han empires

- Malay Chronicles: Bloodlines and Dragon Blade, films based on Sino-Roman relations

- Ancient Greece–Ancient India relations

Notes

- ^ For the assertion that the first Chinese mention of Daqin belongs to the Book of the Later Han, see: Wilkinson (2000), p. 730.

- Hira ("Ho-lat"). Going south of Palmyra and Emesa led one to the "Stony Land", which Hirth identified as Arabia Petraea, due to the text speaking how it bordered a sea (the Red Sea) where corals and real pearls were extracted. The text also explained the positions of border territories that were controlled by Parthia, such as Seleucia ("Si-lo").: Szu-lo).

Hill (September 2004), "Section 14 – Roman Dependencies", identified the dependent vassal states as Azania (Chinese: 澤散; pinyin: Zesan; Wade–Giles: Tse-san), Al Wajh (Chinese: 驢分; pinyin: Lüfen; Wade–Giles: Lü-fen), Wadi Sirhan (Chinese: 且蘭; pinyin: Qielan; Wade–Giles: Ch'ieh-lan), Leukos Limên, ancient site controlling the entrance to the Gulf of Aqaba near modern Aynūnah (Chinese: 賢督; pinyin: Xiandu; Wade–Giles: Hsien-tu), Petra (Chinese: 汜復; pinyin: Sifu; Wade–Giles: Szu-fu), al-Karak (Chinese: 于羅; pinyin: Yuluo; Wade–Giles: Yü-lo), and Sura (Chinese: 斯羅; pinyin: Siluo; Wade–Giles - Macedonian" origin betokens no more than his cultural affinity, and the name Maës is Semitic in origin, Cary (1956), p. 130.

- ^ The mainstream opinion, noted by Cary (1956), p. 130, note #7, based on the date of Marinus of Tyre, established by his use of many Trajanic foundation names but none identifiable with Hadrian.

- Sarikol.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 18; for a discussion of Tiaozhi (条支) and even its etymology possibly stemming from the Tajiks and Iranian peoples under ancient Chinese rule, see footnote #2 on p. 42.

- ^ a b Fan Ye, ed. (1965) [445]. "86: 南蠻西南夷列傳 (Nanman, Xinanyi liezhuan: Traditions of the Southern Savages and South-Western Tribes)". 後漢書 [Book of the Later Han]. Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing. p. 2851. "永寧元年,撣國王雍由調復遣使者詣闕朝賀,獻樂及幻人,能變化吐火,自支解,易牛馬頭。又善跳丸, 數乃至千。自言我海西人。海西即大秦也,撣國西南通大秦。明年元會,安帝作樂於庭,封雍由調爲漢大都尉,賜印綬、金銀、綵繒各有差也。"

A translation of this passage into English, in addition to an explanation of how Greek athletic performers figured prominently in the neighbouring Parthian and Kushan Empires of Asia, is offered by Christopoulos (August 2012), pp. 40–41:The first year of Yongning (120 AD), the southwestern barbarian king of the kingdom of Chan (Burma), Yongyou, proposed illusionists (jugglers) who could metamorphose themselves and spit out fire; they could dismember themselves and change an ox head into a horse head. They were very skilful in acrobatics and they could do a thousand other things. They said that they were from the "west of the seas" (Haixi–Egypt). The west of the seas is the Daqin (Rome). The Daqin is situated to the south-west of the Chan country. During the following year, Andi organized festivities in his country residence and the acrobats were transferred to the Han capital where they gave a performance to the court, and created a great sensation. They received the honours of the Emperor, with gold and silver, and every one of them received a different gift.

- ^ Raoul McLaughlin notes that the Romans knew Burma as India Trans Gangem (India Beyond the Ganges) and that Ptolemy listed the cities of Burma. See McLaughlin (2010), p. 58.

- ^ For information on Matteo Ricci and reestablishment of Western contact with China by the Portuguese Empire during the Age of Discovery, see: Fontana (2011), pp. 18–35, 116–118.

- Kingdom of Funan, see: Suárez (1999), p. 92.

- Kutaradja (Banda Aceh, Indonesia) as other plausible sites for that port. Mawer (2013), p. 38.

References

Citations

- ^ a b British Library. "Detailed record for Harley 7182". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Ostrovsky (2007), p. 44.

- ^ Lewis (2007), p. 143.

- ^ Schoff (1915), p. 237.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 1–2, 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Young (2001), p. 29.

- ^ Raoul McLaughlin (2010), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Suárez (1999), p. 92.

- ^ Wilford (2000), p. 38; Encyclopaedia Britannica (1903), p. 1540.

- ^ a b Parker (2008), p. 118.

- ^ a b Schoff (2004) [1912], Introduction. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Schoff (2004) [1912], Paragraph #64. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), footnote #2 on p. 43.

- ^ a b Mawer (2013), p. 38.

- ^ a b c McLaughlin (2014), p. 205.

- ^ a b Suárez (1999), p. 90.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2021). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 230.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 25.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 28.

- ^ Lieu (2009), p. 227.

- ^ a b c Luttwak (2009), p. 168.

- ^ a b c Luttwak (2009), pp. 168–169.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 29–31; footnote #3 on p. 31.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 30; footnote #2 on p. 30.

- ^ Yule (1915), p 29; footnote #4 on p. 29.

- ^ Haw (2006), pp. 170–171.

- ^ Wittfogel & Feng (1946), p. 2.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Friedrich Hirth (2000) [1885]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham University. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1999), p. 71.

- ^ a b See also Lewis (2007), p. 143.

- ^ a b Pulleyblank (1999), p. 78.

- ^ a b Hoppál, Krisztina (2019). "Chinese Historical Records and Sino-Roman Relations: A Critical Approach to Understand Problems on the Chinese Reception of the Roman Empire". RES Antiquitatis. 1: 63–81.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 41; footnote #4.

- ^ For a review of The Roman Empire as Known to Han China: The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources by D. D. Leslie; K. H. J. Gardiner, see Pulleyblank (1999), pp 71–79; for the specific claim about "Li-Kan" or Lijian see Pulleyblank (1999), p 73.

- ^ Fan, Ye (September 2003). Hill, John E. (ed.). "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan, "Chapter on the Western Regions", from Hou Hanshu 88, Second Edition (Extensively revised with additional notes and appendices): Section 11 – The Kingdom of Daqin 大秦 (the Roman Empire)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1999), pp 73–77; Lijian's identification as Hyrcania was put forward by Marie-Félicité Brosset (1828) and accepted by Markwart, De Groot, and Herrmann (1941). Paul Pelliot advanced the theory that Lijian was a transliteration of Alexandria in Roman Egypt.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Yu, Huan (September 2004). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265, Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi, Published in 429 AD". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Needham (1971), p. 662.

- ^ a b Yu, Huan (September 2004). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265, Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi, Published in 429 CE: Section 11 – Da Qin (Roman territory/Rome)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 46–48.

- ^ Ball (2016), pp. 152–153; see also endnote #114.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 48–49; for a brief summary of Gibbon's account, see also footnote #1 on p. 49.

- ^ Bai (2003), pp 242–247.

- ^ Abraham, Curtis. (11 March 2015). "China’s long history in Africa Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine ". New African. Accessed 2 August 2017.

- ^ Christopoulos (August 2012), pp. 15–16.

- ^ "BBC Western contact with China began long before Marco Polo, experts say". BBC News. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Montgomery, Stephanie; Cammack, Marcus (12 October 2016). "The Mausoleum of China's First Emperor Partners with the BBC and National Geographic Channel to Reveal Groundbreaking Evidence That China Was in Contact with the West During the Reign of the First Emperor". Press release. Business Wire. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Sun (July 2009), p. 7.

- ^ Yang, Juping. “Hellenistic Information in China.” CHS Research Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2014). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:YangJ.Hellenistic_Information_in_China.2014.

- ^ Hill (2009), pp. xiii, 396,

- ^ Stein (1907), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Stein (1933), pp. 47, 292–295.

- ^ Florus, as quoted in Yule (1915), p. 18; footnote #1.

- ^ Florus, Epitome, II, 34

- ^ Tremblay (2007), p. 77.

- ^ Crespigny (2007), p. 590.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 40.

- ^ Crespigny (2007), pp. 590–591.

- ^ a b Crespigny (2007), pp. 239–240.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 5.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1999), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Hill (2009), pp. 5, 481–483.

- ^ a b Fan, Ye (September 2003). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan, "Chapter on the Western Regions", from Hou Hanshu 88, Second Edition (Extensively revised with additional notes and appendices)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Hill (2009), pp. 23, 25.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. xx.

- ^ Book of the Later Han, as quoted in Hill (2009), pp. 23, 25.

- ^ Book of the Later Han, as quoted in Hirth (2000) [1885], online source, retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Kumar (2005), pp. 61–62.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 25.

- ^ Hill, John E. (2012) Through the Jade Gate: China to Rome 2nd edition, p. 55. In press.

- ^ McLaughlin (2014), pp. 204–205.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Christopoulos (August 2012), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Cumont (1933), pp. 264–68.

- ^ Christopoulos (August 2012), p. 41.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), p. 58.

- ^ Braun (2002), p. 260.

- ^ a b c d e f Ball (2016), p. 152.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 600.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 460–461.

- . ctext.org.

- ^ "The First Contact Between Rome and China - Silk-Road.com". Silk Road. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ a b c Hill (2009), p. 27.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 27 and nn. 12.18 and 12.20.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Bang (2009), p. 120.

- ^ de Crespigny. (2007), pp. 597–600.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 52.

- ^ Hirth (1885), pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 53; see footnotes #4–5.

- ^ "During the Taikang Era (280-289) of the reign of Wudi (r.266-290), their King sent an Embassy with tribute" (武帝太康中,其王遣使貢獻) in the account of Daqin (大秦國) in "晉書/卷097". zh.wikisource.org.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Wilkinson (2000), p. 730, footnote #14.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 55–57.

- ^ Yule (1915), footnote #2 of pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Adshead (1995) [1988], p. 105.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Schafer (1985), pp. 10, 25–26.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Adshead (1995) [1988], pp. 104–106.

- ^ Adshead (1995) [1988], p. 104.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 55.

- ^ a b Adshead (1995), pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b Adshead (1995) [1988], p. 106.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-34090-4.

- ^ Old Book of Tang (舊唐書 Jiu Tangshu), ch. 198 (written mid-10th century C.E.), for 618–906 C.E: "開元七年正月,其主遣吐火羅大首領獻獅子、羚羊各二。不數月,又遣大德僧來朝貢" quoted in English translation in Hirth, F. (1885). China and the Roman Orient: Researches into their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records. Shanghai & Hong Kong.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Piras, Andrea (2013). "FROMO KESARO. Echi del prestigio di Bisanzio in Asia Centrale". Polidoro. Studi offerti ad Antonio Carile (in Italian). Spoleto: Centro italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo: 681.

- ^ Martin, Dan (2011). "Greek and Islamic Medicines' Historic Contact with Tibet". In Anna Akasoy; Charles Burnett; Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (eds.). Islam and Tibet – Interactions along the Musk Routes. p. 127.

He received this laudatory epithet because he, like the Byzantines, was successful at holding back the Muslim conquerors.

- )

- ISBN 978-94-93194-01-4.

- ^ Adshead (1995) [1988], pp. 106–107.

- ^ Sezgin (1996), p. 25.

- ^ Bauman (2005), p. 23.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Bretschneider (1888), p. 144.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), p. 169.

- ^ An, (2002), pp. 79, 82–83.

- ^ Spielvogel (2011), p. 183.

- ^ Jacobi (1999), pp. 525–542.

- ^ Reinert (2002), pp. 257–261.

- ^ Wenxian Tongkao, as quoted in Hirth (2000) [1885], online source, retrieved 10 September 2016; in this passage, "Ta-ts'in" is an alternate spelling of "Daqin", the former using the Wade–Giles spelling convention and the latter using pinyin.

- ^ Grant (2005), p. 99.

- ^ Hirth (1885), p. 66.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), p. 170.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), p. 25.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), pp. 34–57.

- ^ de Crespigny. (2007), pp. 514, 600.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), p. 58–60.

- ^ An (2002), p. 82.

- ^ An (2002), p. 83.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Lee, Hee Soo (7 June 2014). "1,500 Years of Contact between Korea and the Middle East". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ "Japanese Tomb Found To House Rare Artifacts From Roman Empire". Huffington Post. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Thorley (1971), pp. 71–80.

- ^ Hill (2009), Appendix B – Sea Silk, pp. 466–476.

- ^ a b Lewis (2007), p. 115.

- ^ Harper (2002), pp. 99–100, 106–107.

- ^ a b Osborne (2006), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 291.

- ^ Ferdinand von Richthofen, China, Berlin, 1877, Vol.I, pp. 504–510; cited in Richard Hennig,Terrae incognitae : eine Zusammenstellung und kritische Bewertung der wichtigsten vorcolumbischen Entdeckungsreisen an Hand der daruber vorliegenden Originalberichte, Band I, Altertum bis Ptolemäus, Leiden, Brill, 1944, pp. 387, 410–411; cited in Zürcher (2002), pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c d O'Reilly (2007), p. 97.

- ^ Young (2001), pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Ball (2016), p. 153.

- ^ Schoff (1915), p. 229.

- ^ Thorley (1979), pp. 181–190 (187f.).

- ^ Thorley (1971), pp. 71–80 (76).

- ^ a b c Whitfield (1999), p. 21.

- sestercesfrom our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what fraction of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?" Original Latin: "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

- ^ Natural History (Pliny), as quoted in Whitfield (1999), p. 21.

- ^ a b c Ball (2016), p. 154.

- ^ Seneca (1974), p. 375.

- ^ a b Ball (2016), pp. 153–154.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 82–83.

- ^ Ball (2016), p. 155.

- ^ a b c Hansen (2012), p. 97.

- ^ "Ancient Roman coins unearthed from castle ruins in Okinawa". The Japan Times. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Howard (2012), p. 133.

- ^ Liu (2001), p. 168.

- ^ Dresden (1981), p. 9.

- ^ Brosius (2006), pp. 122–123.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 79–94.

- ^ Hansen (2012), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Scheidel (2009), p. 186.

- ^ Bagchi (2011), pp. 137–144.

- ^ Scheidel (2009), footnote #239 on p. 186.

- ^ Corbier (2005), p. 333.

- ^ Yule (1915), footnote #1 on p. 44.

- ^ Prowse, Tracy (2010). "Stable isotope and mtDNA evidence for geographic origins at the site of Vagnari, South Italy". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 78: 175–198.

- ^ University, McMaster (2010). "DNA testing on 2,000-year-old bones in Italy reveal East Asian ancestry". phys.org.

- ^ "Skeleton find could rewrite Roman history". BBC News. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- .

- ^ Kristina Killgrove. (23 September 2016). "Chinese Skeletons In Roman Britain? Not So Fast". Forbes. Accessed 25 September 2016.

- ^ Dubs (1941), pp. 322–330.

- ^ Hoh, Erling (May–June 1999). "Romans in China?". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Romans in China stir up controversy". China Daily. Xinhua online. 24 August 2005. Archived from the original on June 24, 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "They came, saw and settled". The Economist. 16 December 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- .

- ^ a b "Hunt for Roman Legion Reaches China". China Daily. Xinhua. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b Squires, Nick (23 November 2010). "Chinese Villagers 'Descended from Roman Soldiers'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ PMID 17579807.

Sources

- Abraham, Curtis. (11 March 2015). "China’s long history in Africa". New African. Accessed 2 August 2017.

- Adshead, S. A. M. (1995) [1988]. China in World History, 2nd edition. New York: Palgrave MacMillan and St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-333-62132-5.

- An, Jiayao. (2002). "When Glass Was Treasured in China", in Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (eds), Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, 79–94. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 2-503-52178-9.

- Bagchi, Prabodh Chandra (2011). Bangwei Wang and Tansen Sen (eds), India and China: Interactions Through Buddhism and Diplomacy: a Collection of Essays by Professor Prabodh Chandra Bagchi. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 93-80601-17-4.

- ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-975835-7.

- ISBN 978-7-101-02890-4.

- Bauman, Richard A. (2005). Crime and Punishment in Ancient Rome. London: Routledge, reprint of 1996 edition. ISBN 0-203-42858-7.

- Braun, Joachim (2002). Douglas W. Scott (trans), Music in Ancient Israel/Palestine: Archaeological, Written, and Comparative Sources. Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-4477-4.

- Bretschneider, Emil (1888). Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century, Vol. 1. Abingdon: Routledge, reprinted 2000.

- Brosius, Maria (2006). The Persians: An Introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32089-5.

- Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)", in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. ISSN 2157-9687.

- ISBN 0-521-30199-8.

- Cumont, Franz (1933). The Excavations of Dura-Europos: Preliminary Reports of the Seventh and Eighth Seasons of Work. New Haven: Crai.

- ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Dresden, Mark J. (1981). "Introductory Note", in Guitty Azarpay (ed.), Sogdian Painting: the Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03765-0.

- Dubs, Homer H. "An Ancient Military Contact between Romans and Chinese", in The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 62, No. 3 (1941), pp. 322–330.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1903) [1890]. Day Otis Kellogg (ed.), The New Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica: a General Encyclopædia of Art, Science, Literature, History, Biography, Invention, and Discovery, Covering the Whole Range of Human Knowledge, Vol. 3. Chicago: Saalfield Publishing (Riverside Publishing).

- Fan, Ye (September 2003). Hill, John E. (ed.). "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan, "Chapter on the Western Regions", from Hou Hanshu 88, Second Edition (Extensively revised with additional notes and appendices)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Fontana, Michela (2011). Matteo Ricci: a Jesuit in the Ming Court. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-0586-4.

- Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK Pub. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Hansen, Valerie (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- Harper, P. O. (2002). "Iranian Luxury Vessels in China From the Late First Millennium B.C.E. to the Second Half of the First Millennium C.E.", in Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (eds), Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, 95–113. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 2-503-52178-9.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the Realm of Kublai Khan. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-34850-1.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hirth, Friedrich (2000) [1885]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham.edu. Fordham University. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Hirth, Friedrich (1885): China and the Roman Orient. 1875. Shanghai and Hong Kong. Unchanged reprint. Chicago: Ares Publishers, 1975.

- Hoh, Erling (May–June 1999). "Romans in China?". Archaeology.org. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: the Role of Cross Border Trade and Travel. McFarland and Company.

- Jacobi, David (1999), "The Latin empire of Constantinople and the Frankish states in Greece", in David Abulafia (ed), The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 525–542. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- Kumar, Yukteshwar. (2005). A History of Sino-Indian Relations, 1st Century A.D. to 7th Century A.D.: Movement of Peoples and Ideas between India and China from Kasyapa Matanga to Yi Jing. New Delhi: APH Publishing. ISBN 81-7648-798-8.

- Lewis, Mark Edward. (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Cambridge: ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- Lieu, Samuel N.C. (2009). "Epigraphica Nestoriana Serica" in Werner Sundermann, Almut Hintze, and Francois de Blois (eds), Exegisti monumenta Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams, pp. 227–246. Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4.

- Liu, Xinru(2001). "The Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Interactions in Eurasia", in Michael Adas (ed.), Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, American Historical Association.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03519-5.

- Mawer, Granville Allen (2013). "The Riddle of Cattigara" in Robert Nichols and Martin Woods (eds), Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, 38–39, Canberra: National Library of Australia. ISBN 978-0-642-27809-8.

- McLaughlin, Raoul (2010). Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India, and China. London: Continuum, ISBN 978-1-84725-235-7.

- McLaughlin, Raoul (2014). The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: the Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia, and India. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-381-7.

- Needham, Joseph (1971). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; rpr. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd, 1986.

- Olschki, Leonardo (1960). Marco Polo's Asia: An Introduction to His "Description of the World" Called "Il Milione". Berkeley: University of California Press and Cambridge University Press.

- O'Reilly, Dougald J.W. (2007). Early Civilizations of Southeast Asia. Lanham: AltaMira Press, Division of Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7591-0279-1.

- Osborne, Milton (2006) [2000]. The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, revised edition. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-893-6

- Ostrovsky, Max (2007). Y = Arctg X: the Hyperbola of the World Order. Lanham: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-3499-0.

- Parker, Grant (2008). The Making of Roman India. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85834-2.

- Pike, John. (last modified 11–07–2011). "Roman Money". Globalsecurity.org. Accessed 14 September 2016.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. "Review: The Roman Empire as Known to Han China: The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources by D. D. Leslie; K. H. J. Gardiner", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119, No. 1 (January–March, 1999), pp. 71–79.

- Reinert, Stephen W. (2002). "Fragmentation (1204–1453)", in Cyril Mango (ed), The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 248–283. ISBN 0-19-814098-3.

- von Richthofen, Ferdinand. (1877). China. Vol.I. Berlin; cited in Richard Hennig (1944), Terrae incognitae : eine Zusammenstellung und kritische Bewertung der wichtigsten vorcolumbischen Entdeckungsreisen an Hand der daruber vorliegenden Originalberichte, Band I, Altertum bis Ptolemäus. Leiden, Brill.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985) [1963]. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T'ang Exotics (1st paperback ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

- ISBN 978-0-19-975835-7.

- Schoff, William H. (2004) [1912]. Lance Jenott (ed.). ""The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century" in The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea". Depts.washington.edu. University of Washington. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Schoff, W. H. (1915). The Eastern Iron Trade of the Roman Empire. [New Haven].

- ISBN 978-0-674-99511-6.

- Sezgin, Fuat; Carl Ehrig-Eggert; Amawi Mazen; E. Neuba uer (1996). نصوص ودراسات من مصادر صينية حول البلدان الاسلامية. Frankfurt am Main: Institut für Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften (Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University). ISBN 9783829820479.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2011). Western Civilization: a Brief History. Boston: Wadsworth, Cencage Learning. ISBN 0-495-57147-4.

- Stein, Aurel M. (1907). Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan. 2 vols. pp. 44–45. M. Aurel Stein. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Stein, Aurel M. (1932), On Ancient Central Asian Tracks: Brief Narrative of Three Expeditions in Innermost Asia and Northwestern China, pp. 47, 292–295. Reprinted with Introduction by Jeannette Mirsky (1999), Delhi: Book Faith India.

- Suárez, Thomas (1999). Early Mapping of Southeast Asia. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 962-593-470-7.

- Sun, Zhixin Jason. "Life and Afterlife in Early Imperial China", in American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 113, No. 3 (July 2009): 1–9. DOI: 10.3764/ajaonline1133.Sun.

- Thorley, John (1971), "The Silk Trade between China and the Roman Empire at Its Height, 'Circa' A. D. 90–130", Greece and Rome, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1971), pp. 71–80.

- Thorley, John. "The Roman Empire and the Kushans", in Greece and Rome, Vol. 26, No. 2 (1979), pp. 181–190 (187f.).

- Tremblay, Xavier (2007). "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century", in Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker (eds), The Spread of Buddhism. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15830-6.

- ISBN 0-520-23214-3.

- Wilford, John Noble (2000) [1981]. The Mapmakers, revised edition. New York: ISBN 0-375-70850-2.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese History: a Manual, Revised and Enlarged. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00247-4.

- Wittfogel, Karl A. and Feng Chia-Sheng. "History of Chinese Society: Liao (907–1125)", in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (vol. 36, Part 1, 1946).

- Yang, Juping. “Hellenistic Information in China.” CHS Research Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2014). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:YangJ.Hellenistic_Information_in_China.2014.

- Young, Gary K. (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC – AD 305. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24219-3.

- Yu, Huan (September 2004). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265, Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi, Published in 429 CE". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. London: Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Zhou R., An L., Wang X., Shao W., Lin G., Yu W., Yi L., Xu S., Xu J., Xie X. "Testing the hypothesis of an ancient Roman soldier origin of the Liqian people in northwest China: a Y-chromosome perspective", in Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 52, No. 7 (2007), pp. 584–91.

- Zürcher, Erik (2002). "Tidings from the South, Chinese Court Buddhism and Overseas Relations in the Fifth Century AD". Erik Zürcher in: A Life Journey to the East. Sinological Studies in Memory of Giuliano Bertuccioli (1923–2001). Edited by Antonio Forte and Federico Masini. Italian School of East Asian Studies. Kyoto. Essays: Volume 2, pp. 21–43.

Further reading

- Leslie, D. D., Gardiner, K. H. J.: "The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources", Studi Orientali, Vol. 15. Rome: Department of Oriental Studies, University of Rome, 1996.

- Schoff, Wilfred H.: "Navigation to the Far East under the Roman Empire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 37 (1917), pp. 240–249

- Bueno, André (May 2016). ""Roman Views of the Chinese in Antiquity" in Sino-Platonic Papers" (PDF). Sino-platonic.org. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

External links

- Accounts of "Daqin" (Roman Empire) in the Chinese history of the Later Han dynasty

- Duncan B. Campbell: Romans in China?

- New Book of Tang passage containing information on Daqin and Fulin (Chinese language source)

- Silk-road.com: The First Contact Between Rome and China