Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Steiner | |

|---|---|

Donji Kraljevec, Croatia) | |

| Died | 30 March 1925 (aged 64) Dornach, Switzerland |

| Education | Vienna Institute of Technology University of Rostock (PhD, 1891) |

| Spouses | |

| Part of a series on |

| Anthroposophy |

|---|

| General |

| Anthroposophically inspired work |

| Philosophy |

| Part of a series on |

| Theosophy |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Esotericism |

|---|

|

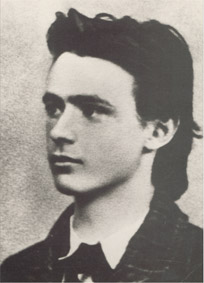

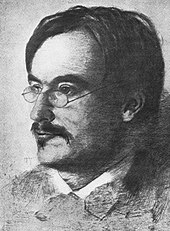

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (27 or 25 February 1861

In the first, more philosophically oriented phase of this movement, Steiner attempted to find a synthesis between

Steiner advocated a form of

Biography

Childhood and education

Steiner's father, Johann(es) Steiner (1829–1910), left a position as a

Steiner entered the village school, but following a disagreement between his father and the schoolmaster, he was briefly educated at home. In 1869, when Steiner was eight years old, the family moved to the village of

In 1879, the family moved to Inzersdorf to enable Steiner to attend the Vienna Institute of Technology,[29] where he enrolled in courses in mathematics, physics, chemistry, botany, zoology, and mineralogy and audited courses in literature and philosophy, on an academic scholarship from 1879 to 1883, where he completed his studies and the requirements of the Ghega scholarship satisfactorily.[30][31] In 1882, one of Steiner's teachers, Karl Julius Schröer,[2]: Chap. 3 suggested Steiner's name to Joseph Kürschner, chief editor of a new edition of Goethe's works,[32] who asked Steiner to become the edition's natural science editor,[33] a truly astonishing opportunity for a young student without any form of academic credentials or previous publications.[34]: 43

Before attending the Vienna Institute of Technology, Steiner had studied

Early spiritual experiences

When he was nine years old, Steiner believed that he saw the spirit of an aunt who had died in a far-off town, asking him to help her at a time when neither he nor his family knew of the woman's death.[35] Steiner later related that as a child, he felt "that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry ... [for here] one is permitted to know something which the mind alone, through its own power, experiences. In this feeling I found the justification for the spiritual world that I experienced ... I confirmed for myself by means of geometry the feeling that I must speak of a world 'which is not seen'."[2]

Steiner believed that at the age of 15 he had gained a complete understanding of the concept of time, which he considered to be the precondition of spiritual clairvoyance.[11] At 21, on the train between his home village and Vienna, Steiner met a herb gatherer, Felix Kogutzki, who spoke about the spiritual world "as one who had his own experience therein".[2]: 39–40 [36]

Writer and philosopher

In 1888, as a result of his work for the Kürschner edition of

In 1891, Steiner received a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Rostock, for his dissertation discussing Fichte's concept of the ego,[22][40] submitted to Heinrich von Stein, whose Seven Books of Platonism Steiner esteemed.[2]: Chap. 14 Steiner's dissertation was later published in expanded form as Truth and Knowledge: Prelude to a Philosophy of Freedom, with a dedication to Eduard von Hartmann.[41] Two years later, in 1894, he published Die Philosophie der Freiheit (The Philosophy of Freedom or The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, the latter being Steiner's preferred English title), an exploration of epistemology and ethics that suggested a way for humans to become spiritually free beings. Steiner hoped that the book "would gain him a professorship", but the book was not well received.[13] Steiner later spoke of this book as containing implicitly, in philosophical form, the entire content of what he later developed explicitly as anthroposophy.[42]

In 1896, Steiner declined an offer from

My first acquaintance with Nietzsche's writings belongs to the year 1889. Previous to that I had never read a line of his. Upon the substance of my ideas as these find expression in The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, Nietzsche's thought had not the least influence....Nietzsche's ideas of the '

eternal recurrence' and of 'Übermensch' remained long in my mind. For in these was reflected that which a personality must feel concerning the evolution and essential being of humanity when this personality is kept back from grasping the spiritual world by the restricted thought in the philosophy of nature characterizing the end of the 19th century....What attracted me particularly was that one could read Nietzsche without coming upon anything which strove to make the reader a 'dependent' of Nietzsche's.[2]: Chap. 18

In 1897, Steiner left the

Despite his fame as a teacher of esotericism, Steiner was culturally and academically isolated.[44]

Theosophical Society

In 1899, Steiner published an article, "Goethe's Secret Revelation", discussing the esoteric nature of Goethe's fairy tale

In contrast to mainstream Theosophy, Steiner sought to build a Western approach to spirituality based on the philosophical and mystical traditions of European culture. The German Section of the Theosophical Society grew rapidly under Steiner's leadership as he lectured throughout much of Europe on his

Anthroposophical Society and its cultural activities

The

Steiner's lecture activity expanded enormously with the end of the war. Most importantly, from 1919 on Steiner began to work with other members of the society to found numerous

At a "Foundation Meeting" for members held at the Dornach center during Christmas 1923, Steiner founded the School of Spiritual Science.

Political engagement and social agenda

Steiner became a well-known and controversial public figure during and after World War I. In response to the catastrophic situation in post-war Germany, he proposed extensive social reforms through the establishment of a

Steiner opposed Wilson's proposal to create new European nations based around ethnic groups, which he saw as opening the door to rampant nationalism. Steiner proposed, as an alternative:

'social territories' with democratic institutions that were accessible to all inhabitants of a territory whatever their origin while the needs of the various ethnicities would be met by independent cultural institutions.[59]

Attacks, illness, and death

The

From 1923 on, Steiner showed signs of increasing frailness and illness. He nonetheless continued to lecture widely, and even to travel; especially towards the end of this time, he was often giving two, three or even four lectures daily for courses taking place concurrently. Many of these lectures focused on practical areas of life such as education.[66]

Increasingly ill, he held his last lecture in late September, 1924. He continued work on his autobiography during the last months of his life; he died at Dornach on 30 March 1925.

Spiritual research

Steiner first began speaking publicly about spiritual experiences and phenomena in his 1899 lectures to the Theosophical Society. By 1901 he had begun to write about spiritual topics, initially in the form of discussions of historical figures such as the mystics of the Middle Ages. By 1904 he was expressing his own understanding of these themes in his essays and books, while continuing to refer to a wide variety of historical sources.

A world of spiritual perception is discussed in a number of writings which I have published since this book appeared. The Philosophy of Freedom forms the philosophical basis for these later writings. For it tries to show that the experience of thinking, rightly understood, is in fact an experience of spirit.

(Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Consequences of Monism)

Steiner aimed to apply his training in

Steiner used the word Geisteswissenschaft (from Geist = mind or spirit, Wissenschaft = science), a term originally coined by Wilhelm Dilthey as a descriptor of the humanities, in a novel way, to describe a systematic ("scientific") approach to spirituality.[72] Steiner used the term Geisteswissenschaft, generally translated into English as "spiritual science," to describe a discipline treating the spirit as something actual and real, starting from the premise that it is possible for human beings to penetrate behind what is sense-perceptible.[73] He proposed that psychology, history, and the humanities generally were based on the direct grasp of an ideal reality,[74] and required close attention to the particular period and culture which provided the distinctive character of religious qualities in the course of the evolution of consciousness. In contrast to William James' pragmatic approach to religious and psychic experience, which emphasized its idiosyncratic character, Steiner focused on ways such experience can be rendered more intelligible and integrated into human life.[75]

Steiner proposed that an understanding of reincarnation and karma was necessary to understand psychology[76] and that the form of external nature would be more comprehensible as a result of insight into the course of karma in the evolution of humanity.[77] Beginning in 1910, he described aspects of karma relating to health, natural phenomena and free will, taking the position that a person is not bound by his or her karma, but can transcend this through actively taking hold of one's own nature and destiny.[78] In an extensive series of lectures from February to September 1924, Steiner presented further research on successive reincarnations of various individuals and described the techniques he used for karma research.[66][79]

Breadth of activity

After the First World War, Steiner became active in a wide variety of cultural contexts. He founded a number of schools, the first of which was known as the

Steiner's literary estate is broad. Steiner's writings, published in about forty volumes, include books, essays, four plays ('mystery dramas'), mantric verse, and an autobiography. His collected lectures, making up another approximately 300 volumes, discuss a wide range of themes. Steiner's drawings, chiefly illustrations done on blackboards during his lectures, are collected in a separate series of 28 volumes. Many publications have covered his architectural legacy and sculptural work.[91][92]

Education

As a young man, Steiner was a private tutor and a lecturer on history for the Berlin Arbeiterbildungsschule,[93] an educational initiative for working class adults.[94] Soon thereafter, he began to articulate his ideas on education in public lectures,[95] culminating in a 1907 essay on The Education of the Child in which he described the major phases of child development which formed the foundation of his approach to education.[96] His conception of education was influenced by the Herbartian pedagogy prominent in Europe during the late nineteenth century,[93]: 1362, 1390ff [95] though Steiner criticized Herbart for not sufficiently recognizing the importance of educating the will and feelings as well as the intellect.[97]

In 1919, Emil Molt invited him to lecture to his workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart. Out of these lectures came the first Waldorf School. In 1922, Steiner presented these ideas at a conference called for this purpose in Oxford by Professor Millicent Mackenzie. He subsequently presented a teacher training course at Torquay in 1924 at an Anthroposophy Summer School organised by Eleanor Merry.[98] The Oxford Conference and the Torquay teacher training led to the founding of the first Waldorf schools in Britain.[99] During Steiner's lifetime, schools based on his educational principles were also founded in Hamburg, Essen, The Hague and London; there are now more than 1000 Waldorf schools worldwide.

Biodynamic agriculture

In 1924, a group of farmers concerned about the future of agriculture requested Steiner's help. Steiner responded with a lecture series on an

"Steiner’s 'biodynamic agriculture' based on 'restoring the quasi-mystical relationship between earth and the cosmos' was widely accepted in the Third Reich (28)."[107]

A central aspect of biodynamics is that the farm as a whole is seen as an organism, and therefore should be a largely self-sustaining system, producing its own

In a 2002 newspaper editorial, Peter Treue, agricultural researcher at the

Anthroposophical medicine

From the late 1910s, Steiner was working with doctors to create a new approach to medicine. In 1921, pharmacists and physicians gathered under Steiner's guidance to create a pharmaceutical company called Weleda which now distributes naturopathic medical and beauty products worldwide. At around the same time, Dr. Ita Wegman founded a first anthroposophic medical clinic (now the Ita Wegman Clinic) in Arlesheim. Anthroposophic medicine is practiced in some 80 countries.[109] It is a form of alternative medicine based on pseudoscientific and occult notions.[110]

Social reform

For a period after World War I, Steiner was active as a lecturer on social reform. A petition expressing his basic social ideas was widely circulated and signed by many cultural figures of the day, including Hermann Hesse.

In Steiner's chief book on

Steiner proposed that societal well-being fundamentally depends upon a relationship of mutuality between the individuals and the community as a whole:

The well-being of a community of people working together will be the greater, the less the individual claims for himself the proceeds of his work, i.e. the more of these proceeds he makes over to his fellow-workers, the more his own needs are satisfied, not out of his own work but out of the work done by others.

— Steiner, The Fundamental Social Law[112]

He expressed another aspect of this in the following motto:

The healthy social life is found

When in the mirror of each human soul

The whole community finds its reflection,

And when in the community

The virtue of each one is living.— Steiner, The Fundamental Social Law[112]

According to Cees Leijenhorst, "Steiner outlined his vision of a new political and social philosophy that avoids the two extremes of capitalism and socialism."[113]

Architecture and visual arts

Steiner designed 17 buildings, including the First and Second Goetheanums.[114] These two buildings, built in Dornach, Switzerland, were intended to house significant theater spaces as well as a "school for spiritual science".[115] Three of Steiner's buildings have been listed amongst the most significant works of modern architecture.[116]

His primary sculptural work is The Representative of Humanity (1922), a nine-meter high wood sculpture executed as a joint project with the sculptor Edith Maryon. This was intended to be placed in the first Goetheanum. It shows a central human figure, the "Representative of Humanity," holding a balance between opposing tendencies of expansion and contraction personified as the beings of Lucifer and Ahriman.[117][118][119] It was intended to show, in conscious contrast to Michelangelo's Last Judgment, Christ as mute and impersonal such that the beings that approach him must judge themselves.[120] The sculpture is now on permanent display at the Goetheanum.

Steiner's blackboard drawings were unique at the time and almost certainly not originally intended as art works.[121] Joseph Beuys' work, itself heavily influenced by Steiner, has led to the modern understanding of Steiner's drawings as artistic objects.[122]

Performing arts

Steiner wrote four

Steiner's plays continue to be performed by anthroposophical groups in various countries, most notably (in the original German) in Dornach, Switzerland and (in English translation) in Spring Valley, New York and in Stroud and Stourbridge in the U.K.In collaboration with Marie von Sivers, Steiner also founded a new approach to acting, storytelling, and the recitation of poetry. His last public lecture course, given in 1924, was on speech and drama. The Russian actor, director, and acting coach Michael Chekhov based significant aspects of his method of acting on Steiner's work.[124][125]

Together with

Esoteric schools

Steiner was founder and leader of the following:

- His independent Esoteric School of the Theosophical Society, founded in 1904. This school continued after the break with Theosophybut was disbanded at the start of World War I.

- A lodge called Mystica Aeterna within the Masonic Order of Memphis and Mizraim, which Steiner led from 1906 until around 1914. Steiner added to the Masonic rite a number of Rosicrucian references.[126]

- The School of Spiritual Science of the Anthroposophical Society, founded in 1923 as a further development of his earlier Esoteric School. This was originally constituted with a general section and seven specialized sections for education, literature, performing arts, natural sciences, medicine, visual arts, and astronomy.[55][57][127] Steiner gave members of the School the first Lesson for guidance into the esoteric work in February 1924.[128] Though Steiner intended to develop three "classes" of this school, only the first of these was developed in his lifetime (and continues today). An authentic text of the written records on which the teaching of the First Class was based was published in 1992.[129]

Philosophical ideas

Goethean science

In his commentaries on Goethe's scientific works, written between 1884 and 1897, Steiner presented Goethe's approach to science as essentially

Particular organic forms can be evolved only from universal types, and every organic entity we experience must coincide with some one of these derivative forms of the type. Here the evolutionary method must replace the method of proof. We aim not to show that external conditions act upon one another in a certain way and thereby bring about a definite result, but that a particular form has developed under definite external conditions out of the type. This is the radical difference between inorganic and organic science.

— Rudolf Steiner, The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World Conception, Chapter XVI, "Organic Nature"

A variety of authors have termed Goethean science pseudoscience.[131][132][133] According to Dan Dugan, Steiner was a champion of the following pseudoscientific claims:

- Goethe's Theory of Colours;[133]

- "he called relativity 'brilliant nonsense'";[133][134]

- "he taught that the motions of the planets were caused by the relationships of the spiritual beings that inhabited them";[133]

- vitalism;[133]

- doubting germ theory;[133]

- non-standard approach to physiological systems, including claiming that the heart is not a pump.[132]

According to Rudolf Steiner, mainstream science is Ahrimanic.[135]

Knowledge and freedom

Steiner approached the philosophical questions of knowledge and freedom in two stages. In his dissertation, published in expanded form in 1892 as Truth and Knowledge, Steiner suggests that there is an inconsistency between Kant's philosophy, which posits that all knowledge is a representation of an essential verity inaccessible to human consciousness, and modern science, which assumes that all influences can be found in the sensory and mental world to which we have access. Steiner considered Kant's philosophy of an inaccessible beyond ("Jenseits-Philosophy") a stumbling block in achieving a satisfying philosophical viewpoint.[136]

Steiner postulates that the world is essentially an indivisible unity, but that our

In The Philosophy of Freedom, Steiner further explores potentials within thinking: freedom, he suggests, can only be approached gradually with the aid of the creative activity of thinking. Thinking can be a free deed; in addition, it can liberate our will from its subservience to our instincts and drives. Free deeds, he suggests, are those for which we are fully conscious of the motive for our action; freedom is the spiritual activity of penetrating with consciousness our own nature and that of the world,[138] and the real activity of acting in full consciousness.[68]: 133–4 This includes overcoming influences of both heredity and environment: "To be free is to be capable of thinking one's own thoughts – not the thoughts merely of the body, or of society, but thoughts generated by one's deepest, most original, most essential and spiritual self, one's individuality."[22]

Steiner affirms

Spiritual science

In his earliest works, Steiner already spoke of the "natural and spiritual worlds" as a unity.[28] From 1900 on, he began lecturing about concrete details of the spiritual world(s), culminating in the publication in 1904 of the first of several systematic presentations, his Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos. As a starting point for the book Steiner took a quotation from Goethe, describing the method of natural scientific observation,[140] while in the Preface he made clear that the line of thought taken in this book led to the same goal as that in his earlier work, The Philosophy of Freedom.[141]

In the years 1903–1908 Steiner maintained the magazine Lucifer-Gnosis and published in it essays on topics such as initiation, reincarnation and karma, and knowledge of the supernatural world.[142] Some of these were later collected and published as books, such as How to Know Higher Worlds (1904–5) and Cosmic Memory. The book An Outline of Esoteric Science was published in 1910. Important themes include:

- the human being as body, soul and spirit;

- the path of spiritual development;

- spiritual influences on world-evolution and history; and

- reincarnation and karma.

Steiner emphasized that there is an objective natural and spiritual world that can be known, and that perceptions of the spiritual world and incorporeal beings are, under conditions of training comparable to that required for the natural sciences, including self-discipline, replicable by multiple observers. It is on this basis that

For Steiner, the cosmos is permeated and continually transformed by the creative activity of non-physical processes and spiritual beings. For the human being to become conscious of the objective reality of these processes and beings, it is necessary to creatively enact and reenact, within, their creative activity. Thus objective spiritual knowledge always entails creative inner activity.[28] Steiner articulated three stages of any creative deed:[68]: Pt II, Chapter 1

- Moral intuition: the ability to discover or, preferably, develop valid ethical principles;

- Moral imagination: the imaginative transformation of such principles into a concrete intention applicable to the particular situation (situational ethics); and

- Moral technique: the realization of the intended transformation, depending on a mastery of practical skills.

Steiner termed his work from this period onwards

Steiner and Christianity

Steiner appreciated the ritual of the mass he experienced while serving as an altar boy from school age until he was ten years old, and this experience remained memorable for him as a genuinely spiritual one, contrasting with his irreligious family life.[145] As a young adult, Steiner had no formal connection to organized religion. In 1899, he experienced what he described as a life-transforming inner encounter with the being of Christ. Steiner was then 38, and the experience of meeting Christ occurred after a tremendous inner struggle. To use Steiner's own words, the "experience culminated in my standing in the spiritual presence of the Mystery of Golgotha in a most profound and solemn festival of knowledge."[146] His relationship to Christianity thereafter remained entirely founded upon personal experience, and thus both non-denominational and strikingly different from conventional religious forms.[22]

Christ and human evolution

Steiner describes Christ as the unique pivot and meaning of earth's evolutionary processes and human history, redeeming

Central principles of his understanding include:

- The being of Christ is central to all religions, though called by different names by each.

- Every religion is valid and true for the time and cultural context in which it was born.

- Historical forms of Christianity need to be transformed in our times in order to meet the ongoing evolution of humanity.

In Steiner's

Divergence from conventional Christian thought

Steiner's views of Christianity diverge from conventional Christian thought in key places, and include

One of the central points of divergence with conventional Christian thought is found in Steiner's views on reincarnation and karma.

Steiner also posited two different Jesus children involved in the Incarnation of the Christ: one child descended from

Steiner's view of the

The Christian Community

In the 1920s, Steiner was approached by

The resulting movement for religious renewal became known as "The Christian Community". Its work is based on a free relationship to Christ without dogma or policies. Its priesthood, which is open to both men and women, is free to preach out of their own spiritual insights and creativity.

Steiner emphasized that the resulting movement for the renewal of Christianity was a personal gesture of help to a movement founded by Rittelmeyer and others independently of his anthroposophical work.[111] The distinction was important to Steiner because he sought with Anthroposophy to create a scientific, not faith-based, spirituality.[147] He recognized that for those who wished to find more traditional forms, however, a renewal of the traditional religions was also a vital need of the times.

Reception

Steiner's work has influenced a broad range of notable personalities. These include:

- philosophers Albert Schweitzer, Owen Barfield and Richard Tarnas;[28]

- writers

- child psychiatrist Eva Frommer;[155]

- music therapist Maria Schüppel[156]

- economist Leonard Read;[157]

- ecologist Rachel Carson;[158]

- artists Joseph Beuys,[159] Wassily Kandinsky,[160][161] and Murray Griffin;[162]

- esotericist and educationalist George Trevelyan;[163]

- actor and acting teacher Michael Chekhov;[164]

- cinema director Andrei Tarkovsky;[165]

- composers Jonathan Harvey[166] and Viktor Ullmann;[167] and

- conductor Bruno Walter.[168]

Albert Schweitzer wrote that he and Steiner had in common that they had "taken on the life mission of working for the emergence of a true culture enlivened by the ideal of humanity and to encourage people to become truly thinking beings".[170] However, Schweitzer was not an adept of mysticism or occultism, but of Age of Enlightenment rationalism.[171]

Anthony Storr stated about Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy: "His belief system is so eccentric, so unsupported by evidence, so manifestly bizarre, that rational skeptics are bound to consider it delusional.... But, whereas Einstein's way of perceiving the world by thought became confirmed by experiment and mathematical proof, Steiner's remained intensely subjective and insusceptible of objective confirmation."[131]

Robert Todd Carroll has said of Steiner that "Some of his ideas on education – such as educating the handicapped in the mainstream – are worth considering, although his overall plan for developing the spirit and the soul rather than the intellect cannot be admired".[172] Translators have pointed out that the German term Geist can be translated equally properly as either mind or spirit, however,[173] and that Steiner's usage of this term encompassed both meanings.[174]

The 150th anniversary of Rudolf Steiner's birth was marked by the first major retrospective exhibition of his art and work, 'Kosmos - Alchemy of the everyday'. Organized by Vitra Design Museum, the traveling exhibition presented many facets of Steiner's life and achievements, including his influence on architecture, furniture design, dance (Eurythmy), education, and agriculture (Biodynamic agriculture).[175] The exhibition opened in 2011 at the Kunstmuseum in Stuttgart, Germany,[176]

The German psychiatrist Wolfgang Treher diagnosed Rudolf Steiner with schizophrenia, in a book from 1966.[177][178]

Heresiology

The teachings of Anthroposophy got called Christian Gnosticism.[15] Indeed, according to the official stance of the Catholic Church, Anthroposophy is "a neognostic heresy".[16] Other heresiologists agree.[17] The Lutheran (Missouri Sinod) apologist and heresiologist Eldon K. Winker quoted Ron Rhodes that Steiner had the same Christology as Cerinthus.[18] Indeed, Steiner thought that Jesus and Christ were two separated beings, who got fused at a certain point in time,[179] which can be construed as Gnostic but not as docetic,[179] since "they do not believe the Christ departed from Jesus prior to the crucfixion".[18]

Two German scholars have called Anthroposophy "the most successful form of 'alternative' religion in the [twentieth] century."[180] Other scholars stated that Anthroposophy is "aspiring to the status of religious dogma".[181]

According to Swartz, Brandt, Hammer, and Hansson, Anthroposophy is a religion.

Robert A. McDermott says Anthroposophy belongs to Christian Rosicrucianism.[192] According to Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Rudolf Steiner "blended modern Theosophy with a Gnostic form of Christianity, Rosicrucianism, and German Naturphilosophie".[193]

Geoffrey Ahern states that Anthroposophy belongs to neo-gnosticism broadly conceived, which he identifies with

Scientism

Race and ethnicity

Steiner's work includes both universalist, humanist elements and racial assumptions.

Steiner occasionally characterized specific

Throughout his life Steiner consistently emphasized the core spiritual unity of all the world's peoples and sharply criticized racial prejudice. He articulated beliefs that the individual nature of any person stands higher than any racial, ethnic, national or religious affiliation.[24][111] His belief that race and ethnicity are transient and superficial, and not essential aspects of the individual,[197] was partly rooted in his conviction that each individual reincarnates in a variety of different peoples and races over successive lives, and that each of us thus bears within him or herself the heritage of many races and peoples.[197][200] Toward the end of his life, Steiner predicted that race will rapidly lose any remaining significance for future generations.[197] In Steiner's view, culture is universal, and explicitly not ethnically based, and he vehemently criticized imperialism.[201]

In the context of his ethical individualism, Steiner considered "race, folk, ethnicity and gender" to be general, describable categories into which individuals may choose to fit, but from which free human beings can and will liberate themselves.[45]

Martins and Vukadinović describe the racism of Anthroposophy as spiritual and paternalistic (i.e. benevolent), in contrast to the materialistic and often malign racism of fascism.

Steiner did influence Italian Fascism, which exploited "his racial and anti-democratic dogma."[204] The fascist ministers Giovanni Antonio Colonna di Cesarò (nicknamed "the Anthroposophist duke"; he became antifascist after taking part in Benito Mussolini's government[205]) and Ettore Martinoli have openly expressed their sympathy for Rudolf Steiner.[204] Most from the occult pro-fascist UR Group were Anthroposophists.[206][207][208]

In fact, "Steiner's collected works, moreover, totalling more than 350 volumes, contain pervasive internal contradictions and inconsistencies on racial and national questions."[209][210]

According to Munoz, in the materialist perspective (i.e. no reincarnations), Anthroposophy is racist, but in the spiritual perspective (i.e. reincarnations mandatory) it is not racist.[211]

Judaism

During the years when Steiner was best known as a literary critic, he published a series of articles attacking various manifestations of antisemitism and criticizing some of the most prominent anti-Semites of the time as "barbaric" and "enemies of culture".[212][213] In contrast, however, Steiner also promoted full assimilation of the Jewish people into the nations in which they lived, suggesting that Jewish cultural and social life had lost its contemporary relevance[214] and "that Judaism still exists is an error of history".[215] Steiner was a critic of his contemporary Theodor Herzl's goal of a Zionist state, and indeed of any ethnically determined state, as he considered ethnicity to be an outmoded basis for social life and civic identity.[216]

Steiner financed the publication of and wrote a foreword for the book Die Entente-Freimaurerei und der Weltkrieg (1919) by Karl Heise, partly based upon his own ideas,[217] a book which has been called "a now classic work of anti-Masonry and anti-Judaism."[218] The publication comprised a conspiracy theory according to which World War I was a consequence of a collusion of Freemasons and Jews their purpose being the destruction of Germany. The writing was later enthusiastically received by the Nazi Party.[219][220]

Writings (selection)

- See also Works in German

The standard edition of Steiner's Collected Works constitutes about 422 volumes. This includes 44 volumes of his writings (books, essay, plays, and correspondence), over 6000 lectures, and some 80 volumes (some still in production) documenting his artistic work (architecture, drawings, paintings, graphic design, furniture design, choreography, etc.).[221] His architectural work, particularly, has also been documented extensively outside of the Collected Works.[92][91]

- Goethean Science (1883–1897)

- Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception (1886)

- Truth and Knowledge, doctoral thesis, (1892)

- Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path, also published as the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity and the ISBN 0-88010-385-X

- Mysticism at the Dawn of Modern Age (1901/1925)

- Christianity as Mystical Fact (1902)

- Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos (1904) ISBN 0-88010-373-6

- How to Know Higher Worlds: A Modern Path of Initiation (1904–5) ISBN 0-88010-508-9

- Cosmic Memory: Prehistory of Earth and Man (1904) (Also published as The Submerged Continents of Atlantis and Lemuria)

- The Education of the Child[ISBN 0-85440-620-4

- The Way of Initiation, (1908) (English edition trans. by Max Gysi)

- Initiation and Its Results, (1909) (English edition trans. by Max Gysi)

- An Outline of Esoteric Science (1910) ISBN 0-88010-409-0

- Four Mystery Dramas (1913)

- The Renewal of the Social Organism (1919)

- Fundamentals of Therapy: An Extension of the Art of Healing Through Spiritual Knowledge (1925)

- Reincarnation and Immortality, Rudolf Steiner Publications. (1970) LCCN 77-130817

- Rudolf Steiner: An Autobiography, Rudolf Steiner Publications, 1977, ISBN 0-8334-0757-0(Originally, The Story of my Life)

- Rudolf Steiner, Friedrich Nietzsche, Fighter for Freedom Garber Communications; 2nd revised edition (July 1985) ISBN 978-0893450335

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ ISBN 3-499-50500-2, p. 8. In 2009 new documentation appeared supporting a date of 27 February : see Günter Aschoff, "Rudolf Steiners Geburtstag am 27. Februar 1861 – Neue Dokumente" Archived 28 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Das Goetheanum 2009/9, pp. 3ff

- ^ a b c d e f g Rudolf Steiner Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life: 1861–1907, Lantern Books, 2006

- ^ "Steiner was born on 25 February 1861 in the village of Kraljevec (in what is today Croatia, but at the time in Hungary)", Heinrich Ullrich, Rudolf Steiner

- ^ "Ich bin...in Ungarn geboren", "ich habe...in Ungarn die ersten eineinhalb Jahre meines Lebens verbracht", Rudolf Steiner, GA174, p. 89

- ^ Steiner was "born February 27, 1861, in Kraljevec, Hungary". Paul M. Allen, "Significant Events in the Life of Rudolf Steiner", in Robert McDermott, New Essential Steiner, SteinerBooks (2009)

- ^ Laszlo, Péter (2011), Hungary's Long Nineteenth Century: Constitutional and Democratic Traditions, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, the Netherlands, p. 7

- ISBN 978-0-333-98454-3

- ^ a b Staudenmaier 2008.

- ^ Some of the literature regarding Steiner's work in these various fields: Goulet, P: "Les Temps Modernes?", L'Architecture D'Aujourd'hui, December 1982, pp. 8–17; Architect Rudolf Steiner Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine at GreatBuildings.com; Rudolf Steiner International Architecture Database; Brennan, M.: Rudolf Steiner ArtNet Magazine, 18 March 1998; Blunt, R.: Waldorf Education: Theory and Practice – A Background to the Educational Thought of Rudolf Steiner. Master Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 1995; Ogletree, E.J.: Rudolf Steiner: Unknown Educator, Elementary School Journal, 74(6): 344–352, March 1974; Nilsen, A.:A Comparison of Waldorf & Montessori Education Archived 10 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, University of Michigan; Rinder, L: Rudolf Steiner's Blackboard Drawings: An Aesthetic Perspective Archived 29 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine and exhibition of Rudolf Steiner's Blackboard Drawings Archived 2 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, at Berkeley Art Museum, 11 October 1997 – 4 January 1998; Aurélie Choné, "Rudolf Steiner's Mystery Plays: Literary Transcripts of an Esoteric Gnosis and/or Esoteric Attempt at Reconciliation between Art and Science?", Aries, Volume 6, Number 1, 2006, pp. 27–58(32), Brill publishing; Christopher Schaefer, "Rudolf Steiner as a Social Thinker", Re-vision Vol 15, 1992; and Antoine Faivre, Jacob Needleman, Karen Voss; Modern Esoteric Spirituality, Crossroad Publishing, 1992.

- ^ "Who was Rudolf Steiner and what were his revolutionary teaching ideas?" Richard Garner, Education Editor, The Independent

- ^ ISBN 0880102071

- ISBN 978-0-19-086757-7.

- ^ a b c Leijenhorst, Cees (2006). "Steiner, Rudolf, * 25.2.1861 Kraljevec (Croatia), † 30.3.1925 Dornach (Switzerland)". In Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (ed.). Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. Leiden / Boston: Brill. p. 1086.

Steiner moved to Weimar in 1890 and stayed there until 1897. He complained bitterly about the bad salary and the boring philological work, but found the time to write his main philosophical works during his Weimar period. ... Steiner's high hopes that his philosophical work would gain him a professorship at one of the universities in the German-speaking world were never fulfilled. Especially his main philosophical work, the Philosophie der Freiheit, did not receive the attention and appreciation he had hoped for.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-5675-8.

In the broadest sense of the term this is any spiritual teaching that says that spiritual knowledge (Greek: gnosis) or wisdom (sophia) rather than doctrinal faith (pistis) or some ritual practice is the main route to supreme spiritual attainment.

- ^ a b Sources for 'Christian Gnosticism':

- Robertson, David G. (2021). Gnosticism and the History of Religions. Scientific Studies of Religion: Inquiry and Explanation. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-350-13770-7. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

Theosophy, together with its continental sister, Anthroposophy... are pure Gnosticism in Hindu dress...

- Gilmer, Jane (2021). The Alchemical Actor. Consciousness, Literature and the Arts. Brill. p. 41. ISBN 978-90-04-44942-8. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

Jung and Steiner were both versed in ancient gnosis and both envisioned a paradigmatic shift in the way it was delivered.

- Quispel, Gilles (1980). Layton, Bentley (ed.). The Rediscovery of Gnosticism: The school of Valentinus. Studies in the history of religions : Supplements to Numen. E.J. Brill. p. 123. ISBN 978-90-04-06176-7. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

After all, Theosophy is a pagan, Anthroposophy a Christian form of modern Gnosis.

- Quispel, Gilles; van Oort, Johannes (2008). Gnostica, Judaica, Catholica. Collected Essays of Gilles Quispel. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies. Brill. p. 370. ISBN 978-90-474-4182-3. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- Carlson, Maria (2018). "Petersburg and Modern Occultism". In Livak, Leonid (ed.). A Reader's Guide to Andrei Bely's "petersburg. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-299-31930-4. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

Theosophy and Anthroposophy are fundamentally Gnostic systems in that they posit the dualism of Spirit and Matter.

- McL. Wilson, Robert (1993). "Gnosticism". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford Companions. Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-19-974391-9. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

Gnosticism has often been regarded as bizarre and outlandish, and certainly it is not easily understood until it is examined in its contemporary setting. It was, however, no mere playing with words and ideas, but a serious attempt to resolve real problems: the nature and destiny of the human race, the problem of *evil, the human predicament. To a gnostic it brought a release and joy and hope, as if awakening from a nightmare. One later offshoot, Manicheism, became for a time a world religion, reaching as far as China, and there are at least elements of gnosticism in such medieval movements as those of the Bogomiles and the Cathari. Gnostic influence has been seen in various works of modern literature, such as those of William Blake and W. B. Yeats, and is also to be found in the Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky and the Anthroposophy of Rudolph Steiner. Gnosticism was of lifelong interest to the psychologist C. G. *Jung, and one of the Nag Hammadi codices (the Jung Codex) was for a time in the Jung Institute in Zurich.

- Robertson, David G. (2021). Gnosticism and the History of Religions. Scientific Studies of Religion: Inquiry and Explanation. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 57.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-7252-3320-1. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

a neognostic heresy

- ^ ISBN 978-1-315-50723-1. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

On the one hand, there are what might be called the Western groups, which reject the alleged extravagance and orientalism of evolved Theosophy, in favor of a serious emphasis on its metaphysics and especially its recovery of the Gnostic and Hermetic heritage. These groups feel that the love of India and its mysteries which grew up after Isis Unveiled was unfortunate for a Western group. In this category there are several Neo-Gnostic and Neo-Rosicrucian groups. The Anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner is also in this category. On the other hand, there are what may be termed "new revelation" Theosophical schisms, generally based on new revelations from the Masters not accepted by the main traditions. In this set would be Alice Bailey's groups, "I Am," and in a sense Max Heindel's Rosicrucianism.

- ^ a b c Sources for 'Christology':

- Winker, Eldon K. (1994). The New Age is Lying to You. Concordia scholarship today. Concordia Publishing House. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-570-04637-0. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

The Christology of Cerinthus is notably similar to that of Rudolf Steiner (who founded the Anthroposophical Society in 1912) and contemporary New Age writers such as David Spangler and George Trevelyan. These individuals all say the Christ descended on the human Jesus at his baptism. But they differ with Cerinthus in that they do not believe the Christ departed from Jesus prior to the crucfixion.12

- Rhodes, Ron (1990). The Counterfeit Christ of the New Age Movement. Christian Research Institute Series. Baker Book House. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8010-7757-9. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- Winker, Eldon K. (1994). The New Age is Lying to You. Concordia scholarship today. Concordia Publishing House. p. 34.

- ^ Sources for 'pseudoscientific':

- Gardner, Martin (1957) [1952]. Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. Dover Books on the Occult. Dover Publications. pp. 169, 224f. ISBN 978-0-486-20394-2. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

The late Rudolf Steiner, founder of the Anthroposophical Society, the fastest growing cult in post-war Germany... Closely related to the organic farming movement is the German anthroposophical cult founded by Rudolf Steiner, whom we met earlier in connection with his writings on Atlantis and Lemuria. ... In essence, the anthroposophists' approach to the soil is like their approach to the human body—a variation of homeopathy. (See Steiner's An Outline of Anthroposophical Medical Research, English translation, 1939, for an explanation of how mistletoe, when properly prepared, will cure cancer by absorbing "etheric forces" and strengthening the "astral body.") They believe the soil can be made more "dynamic" by adding to it certain mysterious preparations which, like the medicines of homeopathic "purists," are so diluted that nothing material of the compound remains.

- Dugan 2007, pp. 74–75

- Ruse, Michael (25 September 2013). The Gaia Hypothesis: Science on a Pagan Planet. University of Chicago Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780226060392. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

We have rather a mishmash of religion on the one hand and pseudoscience on the other, as critics have pointed out (e.g., Shermer 2002, 32). It is hard to tell where one ends and the other begins, but for our purposes it is not really important.

- Regal, Brian (2009). "Astral Projection". Pseudoscience: A Critical Encyclopedia: A Critical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-313-35508-0. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

The Austrian philosopher and occultist Rudolf Steiner (1861 - 1925) claimed that, by astral projection, he could read the Akashic Record. ... Other than anecdotal eyewitness accounts, there is no evidence of the ability to astral project, the existence of other planes, or of the Akashic Record.

- Gorski, David H. (2019). Kaufman, Allison B.; Kaufman, James C. (eds.). Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science. MIT Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-262-53704-9. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

To get an idea of what mystical nonsense anthroposophic medicine is, I like to quote straight from the horse's mouth, namely Physician's Association for Anthroposophic Medicine, in its pamphlet for patients:

- Oppenheimer, Todd (2007). The Flickering Mind: Saving Education from the False Promise of Technology. Random House Publishing Group. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-307-43221-6. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

In Dugan's view, Steiner's theories are simply "cult pseudoscience".

- Ruse, Michael (2013). Pigliucci, Massimo; Boudry, Maarten (eds.). Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. University of Chicago Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-226-05182-6. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

It is not so much that they have a persecution or martyr complex, but that they do revel in having esoteric knowledge unknown to or rejected by others, and they have the sorts of personalities that rather enjoy being on the fringe or outside. Followers of Rudolf Steiner's biodynamic agriculture are particularly prone to this syndrome. They just know they are right and get a big kick out of their opposition to genetically modified foods and so forth.

- Dugan 2002, pp. 31–33

- Kienle, Kiene & Albonico 2006b, pp. 7–18

- Treue 2002

- Storr 1997, pp. 69–70

- Mahner, Martin (2007). Gabbay, Dov M.; Thagard, Paul; Woods, John; Kuipers, Theo A.F. (eds.). General Philosophy of Science: Focal Issues. Handbook of the Philosophy of Science. Elsevier Science. p. 548. ISBN 978-0-08-054854-8. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

Examples of such fields are various forms of "alternative healing" such as shamanism, or esoteric world views like anthroposophy ... For this reason, we must suspect that the "alternative knowledge" produced in such fields is just as illusory as that of the standard pseudosciences.

- Gardner, Martin (1957) [1952]. Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. Dover Books on the Occult. Dover Publications. pp. 169, 224f.

- ^ Sources for 'pseudohistory':

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2009). "Atlantis: Mother of Pseudohistory". Invented Knowledge. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 45, 61. ISBN 978-1-86189-430-4.

For the Theosophists and other occultists Atlantis has a greater importance since it forms an integral part of their religious worldview.

- Staudenmaier, Peter (2014). Between Occultism and Nazism: Anthroposophy and the Politics of Race in the Fascist Era. Aries Book Series. Brill. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-04-27015-2. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

In Steiner's view, "ordinary history" was "limited to external evidence" and hence no match for "direct spiritual perception."22 Indeed for anthroposophists, "conventional history" constitutes "a positive hindrance to occult research."23

- Gardner 1957, pp. 169, 224f

- Lachman, Gary (2007). Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Penguin Publishing Group. pp. xix, 233. ISBN 978-1-101-15407-6. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

I formulated the cognitive challenge I was presenting myself with in this way: How can I account for the fact that, on one page, Steiner can make a powerful and original critique of Kantian epistemology—basically, the idea that there are limits to knowledge—yet on another make, with all due respect, absolutely outlandish and, more to the point, seemingly unverifiable statements about life in ancient Atlantis?

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2009). "Atlantis: Mother of Pseudohistory". Invented Knowledge. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 45, 61.

- ISBN 978-1-55458-028-6, p. 32

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8245-1444-0.

- ISBN 587317-6604.

- ^ ISBN 3-499-50500-2, pp. 123–6

- ^ a b Paull, John (2011). "Attending the First Organic Agriculture Course: Rudolf Steiner's Agriculture Course at Koberwitz, 1924" (PDF). European Journal of Social Sciences. 21 (1): 64–70.

- ^ Steiner, Rudolf (1883), Goethean Science, GA1.

- ^ Zander, Helmut; Fernsehen, Schweizer (15 February 2009), Sternstunden Philosophie: Die Anthroposophie Rudolf Steiners (program) (in German).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lachman 2007

- ^ In Austria passing the matura examination at a Gymnasium (school) was required for entry to the University.[1] Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sam, Martina Maria (2020). "Warum machte Rudolf Steiner keine Abschlussprüfung an der Technischen Hochschule?". Das Goetheanum. Marginalien zu Rudolf Steiner's Leben und Werk. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ There was some controversy over this matter as researchers failed to note that at the time no "degrees" in the modern manner were awarded in Germany and Austria except doctorates. The research by Dr Sam confirms the details. Rudolf Steiner studied for eight semesters at the Technical University in Vienna - as a student in the General Department, which was there in addition to the engineering, construction, mechanical engineering and chemical schools. The general department comprised all subjects that could not be clearly assigned to one of these four existing technical schools. Around 1880 this included mathematics, descriptive geometry, physics, as well as general and supplementary subjects such as German language and literature, history, art history, economics, legal subjects, languages, The students in the General Department - unlike their fellow students in the specialist departments - neither had to complete a fixed curriculum nor take a final or state examination. They did not have to and could not - because that was not intended for this department, nor was the "Absolutorium". Final state examinations at the Vienna University of Technology only began in the academic year 1878/79. The paper reports how at that time, the so-called ‘individual examinations’ in the subjects studied seemed to be of greater importance and were reported first in the 'Annual Report of the Technical University 1879/80' - sorted according to the faculties of the Technical University. Steiner was in fact amongst the best student on these grounds and was cited by the University as one of its distinguished alumni. The records for the examinations he sat are on record as is the scholarship record.

- ^ Ahern 2009.

- ^ Alfred Heidenreich, Rudolf Steiner – A Biographical Sketch

- ^ Zander, Helmut (2011). Rudolf Steiner: Die Biografie. Munich: Piper.

- ^ The Collected Works of Rudolf Steiner. Esoteric Lessons 1904–1909. SteinerBooks, 2007.

- ^ Steiner, GA 262, pp. 7–21.

- ^ "Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World Conception", also translated as Goethe's Theory of Knowledge, An Outline of the Epistemology of His Worldview

- ^ Preface to 1924 edition of The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception, with Specific Reference to Schiller, in which Steiner also wrote that the way of knowing he presented in this work opened the way from the sensory world to the spiritual one.

- ISBN 978-0-936132-92-1, link

- Wissenschaftslehre– Prolegomena zur Verständigung des philosophierenden Bewusstseins mit sich selbst.

- ^ Truth and Knowledge (full text). German: Wahrheit und Wissenschaft – Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Freiheit

- ^ Sergei Prokofieff, May Human Beings Hear It!, Temple Lodge, 2004. p. 460

- ISBN 978-0893450335. Online [2]

- ^ Leijenhorst 2006, p. 1088: "Despite his success as an esoteric teacher, Steiner seems to have suffered from being shut off from academic and general cultural life, given his continued attempts at getting academic positions or jobs as a journalist."

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8305-1613-2, pp. 184f

- ISBN 1-85584-051-0.

- ISBN 9780521019569. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ISBN 0-14-400006-7

- ^ Zimmermann's Geschichte der Aesthetik als philosophische Wissenschaft.: Anthroposophie im Umriss-Entwurf eines Systems idealer Weltansicht auf realistischer Grundlage: Steiner, Anthroposophic Movement: Lecture Two: The Unveiling of Spiritual Truths, 11 June 1923.[3]. Steiner took the name but not the limitations on knowledge which Zimmerman proposed. Steiner, The Riddles of Philosophy (1914), Chapter VI, "Modern Idealistic World Conceptions" [4]

- .

- ^ Paull, John (2019) Rudolf Steiner: At Home in Berlin, Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania. 132: 26-29.

- ^ Paull, John (2018) The Home of Rudolf Steiner: Haus Hansi, Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania, 126:19-23.

- ISBN 978-3-7274-2590-5.

- ISBN 1902636805

- ^ a b 1923/1924 Restructuring and deepening. Refounding of the Anthroposophical Society Archived 21 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Goetheanum website

- ISBN 9781855843820

- ^ a b "Christmas Conference: Lecture 9: Continuation of the Foundation Meeting, 28 December, 10 a.m." wn.rsarchive.org. 19 November 1990.

- ^ Frankfurter Zeitung, 4 March 1921

- ^ Uwe Werner (2011), "Rudolf Steiner zu Individuum und Rasse: Sein Engagement gegen Rassismus und Nationalismus", in Anthroposophie in Geschichte und Gegenwart. trans. Margot M. Saar

- ^ a b Uwe Werner, Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, Munich (1999), p. 7.

- ^ "Hitler Attacks Rudolf Steiner". www.defendingsteiner.com.

- ^ Rudolf Steiner, The Esoteric Aspect of the Social Question: The Individual and Society, Steinerbooks, p xiv and see also Lindenberg, Rudolf Steiner: Eine Biographie, pp. 769–70

- ^ "Riot at Munich Lecture", New York Times, 17 May 1922.

- ^ Marie Steiner, Introduction, in Rudolf Steiner, Turning Points in Spiritual History, Dornach, September 1926.

- ^ Wiesberger, Die Krise der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft 1923 Archived 6 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISBN 3-7725-1551-7

- ^ Lindenberg, "Schritte auf dem Weg zur Erweiterung der Erkenntnis", pp. 77ff

- ^ ISBN 3-608-93006-X

- ^ Steiner described Brentano's Psychology from the Empirical Standpoint (1870) as symptomatic of the weakness of a psychology that intended to follow the method of natural science but lacked the strength and elasticity of mind to do justice to the demand of modern times: Steiner, The Riddles of Philosophy (1914), Chapter VI, "Modern Idealistic World Conceptions" [5]

- ISBN 0-88010-115-6

- ISBN 0-940262-82-7

- ^ Dilthey had used this term in the title of one of the works listed in the Introduction to Steiner's Truth and Science (his doctoral dissertation) as concerned with the theory of cognition in general: Einleitung in die Geisteswissenschaften, usw., (Introduction to the Spiritual Sciences, etc.) published in 1883."Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ Steiner, "The Mission of Spiritual Science", lecture 1 of Metamorphoses of the Soul: Paths of Experience, Vol. 1

- ^ The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception, ch XIX

- ^ William James and Rudolf Steiner, Robert A. McDermott, 1991, in ReVision, vol.13 no.4 [6] Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rudolf Steiner, Reincarnation and Karma: Concepts Compelled by the Modern Scientific Point of view, in Lucifer Gnosis 1903.[7]

- ^ "Introductory note to Karmic Relationships".

- ISBN 1855840588. Online [8]

- ^ These lectures were published as Karmic Relationships: Esoteric Studies

- ^ IN CONTEXT No. 6, Summer 1984

- ^ "ATTRA – National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service". Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

- ISBN 9783794524952.

- PMID 18540325.

- ^ "Camphill list of communities". Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Both Goetheanum buildings are listed as among the most significant 100 buildings of modern architecture by Goulet, Patrice, Les Temps Modernes?, L'Architecture D'Aujourd'hui, December 1982

- ^ Rudolf Steiner Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Great Buildings Online

- ^ Michael Brennan, rudolf steiner, Artnet

- ^ Hortola, Policarp. "The Aesthetics of haemotaphonomy: A study of the stylistic parallels between a science and literature and the visual arts". Eidos 2009, n.10, pp. 162-193

- ^ Spirituelles Gemeinschaftswerk Das Erste Goetheanum in Dornach – eine Ausstellung im Schweizerischen Architekturmuseum Basel, Neue Zurcher Zeitung 10.5.2012

- ISBN 978-3-7725-0240-8.

- ^ ISBN 9780854403554.

- ^ ISBN 9783832190125.

- ^ a b Zander, Helmut (2007). Anthroposophie in Deutschland. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- .

- ^ ISBN 9780826484192.

- ^ The original essay was published in the journal Lucifer-Gnosis in 1907 and can be found in Steiner's collected essays, Lucifer-Gnosis 1903-1908,

GA34. This essay was republished as an independent brochure in 1909; in a Prefatory note to this edition[ISBN 978-0-88010-414-2)

- ISBN 9780880103947. pp. 15-23

- ^ Paull, John (2018) Torquay: In the Footsteps of Rudolf Steiner, Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania. 125 (Mar): 26–31.

- ISBN 0910142939. p. 267

- ^ Paull, John (July 2015). "The Secrets of Koberwitz: The Diffusion of Rudolf Steiner's Agriculture Course and the Founding of Biodynamic Agriculture" (PDF). Journal of Social Research & Policy. 2 (1): 19–29. Archived from the original on 25 November 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ .

- ^ Purvis, Andrew (6 December 2009). "Biodynamic coffee farming in Brazil". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Biodynamic Agricultural Association of Southern Africa - Green Africa Directory". Green Africa Directory. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ a b Paull, John (2011) "Biodynamic Agriculture: The Journey from Koberwitz to the World, 1924–1938", Journal of Organic Systems, 2011, 6(1):27–41.

- ^ Groups in N. America, List of Demeter certifying organizations, Other biodynamic certifying organization, Some farms in the world

- ^ How to Save the World: One Man, One Cow, One Planet; Thomas Burstyn

- ^ Purcell, Brendan (24 June 2018). "Hitler's Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich". VoegelinView. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Treue, Peter (13 March 2002). "Blut und Bohnen: Der Paradigmenwechsel im Künast-Ministerium ersetzt Wissenschaft durch Okkultismus". Die Gegenwart (in German). Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived from the original on 17 April 2003. Retrieved 15 November 2011. (Translation: "Blood and Beans: The paradigm shift in the Ministry of Renate Künast replaces science with occultism")

- PMID 24416705.

- PMID 18540325.

- ^ ISBN 0-06-065345-0.

- ^ ISBN 1 85584 005 7

- ISBN 978-90-04-14187-2. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

Steiner outlined his vision of a new political and social philosophy that avoids the two extremes of capitalism and socialism.

- ISBN 978-1-317-41950-1.

- ISBN 5873176604. (In Russian with the summary in English) [www.iartforum.com]

- ^ Goulet, P: "Les Temps Modernes?", L'Architecture D'Aujourd'hui, December 1982, pp. 8–17.

- ISBN 0 88010 396 5

- ISBN 9781855842397 from the German Die Holzplastik des Goetheanum (2008) [9] Archived 2 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rudolf Steiner Christ in Relation to Lucifer and Ahriman, lecture May,1915 [10]

- ^ Rudolf Steiner, The Etheric Body as a Reflexion of the Universe lecture, June 1915 [11]

- ^ "Thought-Pictures - Rudolf Steiner's Blackboard Drawings". Archived from the original on 4 May 2014.

- ^ Lawrence Rinder, Rudolf Steiner: An Aesthetic Perspective Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0-936132-93-0

- ^ Anderson, Neil (June 2011). "On Rudolf Steiner's Impact on the Training of the Actor". Literature & Aesthetics. 21 (1).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Richard Solomon, Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training Archived 3 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, MA thesis University of Maine, 2002

- ^ Ellic Howe: The Magicians of the Golden Dawn London 1985, Routledge, pp 262 ff

- ^ Elisabeth Vreede, who Steiner had nominated as the first leader of the Mathematical-Astronomical Section, was responsible for the posthumous 1926 edition of Steiner's astronomy course, concerning this branch of natural science from the point of view of Anthroposophy and spiritual science, under the title The Relationship of the various Natural-Scientific Subjects to Astronomy, [12]

- ^ Wachsmuth et al. 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Johannes Kiersch, A History of the School of Spiritual Science: The First Class, Temple Lodge Publishing, 2006, p.xii. The detailed account is given in chapter 8

- ^ ISBN 3-499-50079-5)

- ^ ISBN 0-684-83495-2.

His belief system is so eccentric, so unsupported by evidence, so manifestly bizarre, that rational skeptics are bound to consider it delusional.... But, whereas Einstein's way of perceiving the world by thought became confirmed by experiment and mathematical proof, Steiner's remained intensely subjective and insusceptible of objective confirmation.

- ^ ISBN 9781615922802. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

Anthroposophical pseudoscience is easy to find in Waldorf schools. "Goethean science" is supposed to be based only on observation, without "dogmatic" theory. Because observations make no sense without a relationship to some hypothesis, students are subtly nudged in the direction of Steiner's explanations of the world. Typical departures from accepted science include the claim that Goethe refuted Newton's theory of color, Steiner's unique "threefold" systems in physiology, and the oft-repeated doctrine that "the heart is not a pump" (blood is said to move itself).

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57607-653-8.

In physics, Steiner championed Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's color theory over Isaac Newton, and he called relativity "brilliant nonsense." In astronomy, he taught that the motions of the planets were caused by the relationships of the spiritual beings that inhabited them. In biology, he preached vitalism and doubted germ theory.

- ISSN 0010-5155.

- ^ Sources for 'Ahrimanic':

- Steiner, Rudolf (1985). "1. Forgotten Aspects of Cultural Life". Karma of Materialism: 9 Lectures, Berlin, July 31–Sept. 25, 1917 (CW 176). SteinerBooks. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-62151-025-3. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

The whole content of natural science is ahrimanic and will only lose its ahrimanic nature when it becomes imbued with life.

- Steiner, Rudolf; Meuss, Anna R. (1993). The Fall of the Spirits of Darkness. Rudolf Steiner Press. p. 160-161. ISBN 978-1-85584-010-2. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- Steiner, Rudolf; Barton, Matthew (2013). The Incarnation of Ahriman: The Embodiment of Evil on Earth. Rudolf Steiner Press. p. 53-54. ISBN 978-1-85584-278-6. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- Wachsmuth, Guenther; Garber, Bernard J.; Wannamaker, Olin D.; Raab, Reginald E. (1995). The Life and Work of Rudolf Steiner: From the Turn of the Century to His Death. SteinerBooks. p. unpaginated. ISBN 978-1-62151-053-6. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

and all external science, to the extent that it is not spiritual science, is Ahrimanic.

- Al-Faruqi, Ismail Il Raji (1977). "Moral values in medicine and science". Biosciences Communications. 3 (1). S. Karger.: 56–58. ISSN 0302-2781. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- Prokofieff, Sergei O. (1998). The Case of Valentin Tomberg: Anthroposophy Or Jesuitism?. Temple Lodge. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-904693-85-0. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- Younis, Andrei (2015). Islam in Relation to the Christ Impulse: A Search for Reconciliation between Christianity and Islam. SteinerBooks. p. unpaginated. ISBN 978-1-58420-185-4. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

Steiner emphasized that, when this deadened wisdom of Gondishapur began to spread in Europe, an ahrimanic, or ahrimanically inspired, natural science began to emerge.

- Selg, Peter (2022). The Future of Ahriman and the Awakening of Souls: The Spirit-Presence of the Mystery Dramas. Rudolf Steiner Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-912230-92-1. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- Steiner, Rudolf (1985). "1. Forgotten Aspects of Cultural Life". Karma of Materialism: 9 Lectures, Berlin, July 31–Sept. 25, 1917 (CW 176). SteinerBooks. p. 34.

- ^ Storr 1997, p. 72: "If, however, we regard the sum of all percepts as the one part and contrast with this a second part, namely the things-in-themselves, then we are philosophising into the blue. We are merely playing with concepts."

- ^ Steiner, Rudolf, Truth and Science, Preface.

- ^ "To be conscious of the laws underlying one's actions is to be conscious of one's freedom. The process of knowing ... is the process of development towards freedom." Steiner, GA3, pp. 91f, quoted in Rist and Schneider, p. 134

- ISBN 0-7126-7332-6. Cf. Solovyov: "In human beings, the absolute subject-object appears as such, i.e. as pure spiritual activity, containing all of its own objectivity, the whole process of its natural manifestation, but containing it totally ideally – in consciousness....The subject knows here only its own activity as an objective activity (sub specie object). Thus, the original identity of subject and object is restored in philosophical knowledge." (The Crisis of Western Philosophy, Lindisfarne 1996 pp. 42–3)

- ^ "Theosophy: Chapter I: The Nature of Man". wn.rsarchive.org.

- ^ Theosophy, from the Prefaces to the First, Second, and Third Editions [13]

- ^ e.Librarian, The. "Rudolf Steiner Archive: Steiner Articles Bn/GA 34". www.rsarchive.org.

- ISBN 0880104368

- ^ One of Steiner's teachers, Franz Brentano, had famously declared that "The true method of philosophy can only be the method of natural science" (Walach, Harald, "Criticism of Transpersonal Psychology and Beyond", in The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology, ed. H. L. Friedman and G. Hartelius. P. 45.)

- OCLC 11145259.

- ^ Autobiography, Chapters in the Course of My Life: 18611907, Rudolf Steiner, SteinerBooks, 2006

- ^ ISSN 0030-9230Especially chapters 1.3, 1.4.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link - ^ An Outline of Esoteric Science, Anthroposophic, SteinerBooks, 1997

- ^ Fulford, Robert (23 October 2000). "Bellow: the novelist as homespun philosopher". The National Post. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Andrey Bely". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 June 2002.

- ISBN 3643901542

- ^ J.D. Elsworth, Andrej Bely:A Critical Study of the Novels, Cambridge:1983, cf. [14]

- ^ Michael Ende biographical notes Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, "Michael Ende und die magischen Weltbilder"

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1909". NobelPrize.org.

- ISBN 978-1-869890-59-9.

- ^ "Musiktherapie". www.musiktherapeutische-arbeitsstaette.de. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Shearmur, Jeremy (1 September 2015). "The Birth of Leonard Read's "I, Pencil" | Jeremy Shearmur". fee.org. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- .

- ^ John F. Moffitt, "Occultism in Avant-Garde Art: The Case of Joseph Beuys", Art Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, (Spring, 1991), pp. 96–98

- ^ Peg Weiss, "Kandinsky and Old Russia: The Artist as Ethnographer and Shaman", The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Summer, 1997), pp. 371–373

- ^ "Kandinsky: The Path to Abstraction 1908 - 1922". www.artsablaze.co.uk.

- ^ Alana O'Brien, In Search of the Spiritual: Murray Griffin's View of the Supersensible World, La Trobe University Museum of Art, 2009

- ^ Michael Barker, Sir George Trevelyan's Life Of Magic, Swans Commentary, 5 November 2012

- S2CID 145199571.

- ^ Layla Alexander Garrett on Tarkovsky Archived 27 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Nostalgia.com

- ^ Alexandra Coghlan "Weltethos: CBSO, Gardner, Royal Festival Hall" ArtsDesk 08/10/2012

- ^ Gwyneth Bravo, Viktor Ullmann

- ^ Bruno Walter, "Mein Weg zur Anthroposophie". In: Das Goetheanum 52 (1961), 418–2

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-49399-5. Retrieved 21 January 2022. See also p. 98, where Hammer states that – unusually for founders of esoteric movements – Steiner's self-descriptions of the origins of his thought and work correspond to the view of external historians.

- ^ "Albert Schweitzer's Friendship with Rudolf Steiner". www.theosophyforward.com.

- ISBN 978-0-19-108704-2. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

Schweitzer felt closest intellectually to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment

- ^ Robert Todd Carroll (12 September 2004). "The Skeptic's Dictionary: Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925)". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ J. B. Baillie (trans.), in Hegel, The Phenomenology of Mind, v. 2, London: Swan Sonnenschein. p. 429

- ISBN 0-88010-018-4. p. 125, fn. 1

- ^ Paull, John (2011) Rudolf Steiner - Alchemy of the Everyday - Kosmos - A photographic review of the exhibition

- ^ Paull, John (2011) "A Postcard from Stuttgart: Rudolf Steiner's 150th anniversary exhibition 'Kosmos'", Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania, 103 (September), pp. 8–11.

- .

- ^ "Hitler, Steiner, Schreber". trehers Webseite! (in German). Retrieved 30 December 2023.

Eingeordnet in eine psychiatrische Krankenvorstellung lassen sich Hitler und Steiner als sozial scheinangepasste Schizophrene klassifizieren.

- ^ a b Leijenhorst, Cees (2006b). "Antroposophy". In Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (ed.). Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. Leiden / Boston: Brill. p. 84.

Nevertheless, he made a distinction between the human person Jesus, and Christ as the divine Logos.

- ^ Schnurbein & Ulbricht 2001, p. 38.

- ^ Diener & Hipolito 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Sources for 'religion':

- Schnurbein, Stefanie von; Ulbricht, Justus H. (2001). Völkische Religion und Krisen der Moderne: Entwürfe "arteigener" Glaubenssysteme seit der Jahrhundertwende (in German). Königshausen & Neumann. p. 38. ISSN 1092-6690.

- Swartz, Karen; Hammer, Olav (14 June 2022). "Soft charisma as an impediment to fundamentalist discourse: The case of the Anthroposophical Society in Sweden". Approaching Religion. 12 (2): 18–37. ISSN 1799-3121.

2. It can be noted that insiders routinely deny that Anthroposophy is a religion and prefer to characterise it as, for example, a philosophical perspective or a form of science. From a scholarly perspective, however, Anthroposophy has all the elements that one typically associates with a religion, for example, a charismatic founder whose status is based on claims of having direct insight into a normally invisible spiritual dimension of existence, a plethora of culturally postulated suprahuman beings that are said to influence our lives, concepts of an afterlife, canonical texts and rituals. Religions whose members deny that the movement they belong to has anything to do with religion are not uncommon in the modern age, but the reason for this is a matter that goes beyond the confines of this article.

- Brandt, Katharina; Hammer, Olav (2013). "Rudolf Steiner and Theosophy". In Hammer, Olav; Rothstein, Mikael (eds.). Handbook of the Theosophical Current. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Brill. p. 113 fn. 1. ISBN 978-90-04-23597-7. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

From a scholar's point of view, Anthroposophy presents characteristics typically associated with religion, and in particular concepts of suprahuman agents (such as angels), a charismatic founder with postulated insight into the suprahuman realm (Steiner himself), rituals (for instance, eurythmy), and canonical texts (Steiner's writings). From an insider's perspective, however, "anthroposophy is not a religion, nor is it meant to be a substitute for religion. While its insights may support, illuminate or complement religious practice, it provides no belief system" (from the Waldorf school website www.waldorfanswers.com/NotReligion1.htm , accessed 9 October 2011). The contrast between a scholarly and an insiders' perspective on what constitutes religion is highlighted by the clinching warrant for this assertion. Although the website argues that Anthroposophy is not a religion by stating that there are no spiritual teachers and no beliefs, it does so by adding a reference to a text by Steiner, who thus functions as an unquestioned authority figure.

- Hammer, Olav (2008). Geertz, Armin; Warburg, Margit (eds.). New Religions and Globalization. Renner Studies On New Religions. Aarhus University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-87-7934-681-9. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

Anthroposophy is thus from an emic point of view emphatically not a religion.

- Hansson, Sven Ove (1 July 2022). "Anthroposophical Climate Science Denial". Critical Research on Religion. 10 (3). SAGE Publications: 281–297. ISSN 2050-3032.

Anthroposophy has characteristics usually associated with religions, not least a belief in a large number of spiritual beings (Toncheva 2015, 73–81, 134–135). However, its adherents emphatically reject that it is a religion, claiming instead that it is a spiritual science, Geisteswissenschaft (Zander 2007, 1:867).

- Zander, Helmut (2002). "Die Anthroposophie — Eine Religion?". In Hoheisel, Karl; Hutter, Manfred; Klein, Wolfgang Wassilios; Vollmer, Ulrich (eds.). Hairesis: Festschrift für Karl Hoheisel zum 65. Geburtstag. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum (in German). Aschendorff. p. 537. ISBN 978-3-402-08120-4. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- See also International Bureau of Education (1960). Organization of Special Education for Mentally Deficient Children: A Study in Comparative Education. UNESCO. p. 15. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

anthroposophy - a religion based upon the philosophical and scientific knowledge of man

- See also International Bureau of Education (1957). Bulletin of the International Bureau of Education. International Bureau of Education. p. 36. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

anthroposophy - a religion based upon the philosophical and scientific knowledge of man

- Schnurbein, Stefanie von; Ulbricht, Justus H. (2001). Völkische Religion und Krisen der Moderne: Entwürfe "arteigener" Glaubenssysteme seit der Jahrhundertwende (in German). Königshausen & Neumann. p. 38.

- ^ Swartz & Hammer 2022, pp. 18–37.

- ^ Sources for 'cult' or 'sect':

- Gardner 1957, pp. 169, 224f

- Brown, Candy Gunther (6 May 2019). "Waldorf Methods". Debating Yoga and Mindfulness in Public Schools. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 229–254. S2CID 241945146.

premised on anthroposophy, a religious sect founded by Steiner;

- ^ Toncheva 2013, pp. 81–89.

- ^ Clemen 1924, pp. 281–292.

- ^ Sources for 'new religious movement':

- Norman, Alex (2012). Cusack, Carole M.; Norman, Alex (eds.). Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Brill. p. 213. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- Frisk, Liselotte (2012). Cusack, Carole M.; Norman, Alex (eds.). Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Brill. p. 204 fn. 10, 208. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

Thus my conclusion is that it is quite uncontroversial to see Anthroposophy as a whole as a religious movement, in the conventional use of the term, although it is not an emic term used by Anthroposophists themselves.

- Cusack, Carole M. (2012). Cusack, Carole M.; Norman, Alex (eds.). Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Brill. p. 190. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

Steiner, of all esoteric and new religious teachers of the early twentieth century, was acutely aware of the peculiar value of cultural production, an activity with which he engaged with tireless energy, and considerable (amateur and professional) skill and achievement.

- Gilhus, Sælid (2016). Bogdan, Henrik; Hammer, Olav (eds.). Western Esotericism in Scandinavia. Brill Esotericism Reference Library. Brill. p. 56. ISBN 978-90-04-32596-8. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- Ahlbäck, Tore (1 January 2008). "Rudolf Steiner as a religious authority". Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis. 20. ISSN 2343-4937.

- Toncheva, Svetoslava (2013). "Anthroposophy as religious syncretism". SOTER: Journal of Religious Science. 48 (48): 81–89. .