Russia

- Acèh

- Адыгэбзэ

- Адыгабзэ

- Afrikaans

- Alemannisch

- Алтай тил

- አማርኛ

- Anarâškielâ

- अंगिका

- Ænglisc

- Аԥсшәа

- العربية

- Aragonés

- ܐܪܡܝܐ

- Արեւմտահայերէն

- Armãneashti

- Arpetan

- অসমীয়া

- Asturianu

- Atikamekw

- अवधी

- Avañe'ẽ

- Авар

- Aymar aru

- Azərbaycanca

- تۆرکجه

- Basa Bali

- Bamanankan

- বাংলা

- Banjar

- Bân-lâm-gú

- Basa Banyumasan

- Башҡортса

- Беларуская

- Беларуская (тарашкевіца)

- भोजपुरी

- Bikol Central

- Bislama

- Български

- Boarisch

- བོད་ཡིག

- Bosanski

- Brezhoneg

- Буряад

- Català

- Чӑвашла

- Cebuano

- Čeština

- Chamoru

- Chavacano de Zamboanga

- Chi-Chewa

- ChiShona

- ChiTumbuka

- Corsu

- Cymraeg

- Dagbanli

- Dansk

- الدارجة

- Davvisámegiella

- Deitsch

- Deutsch

- ދިވެހިބަސް

- Diné bizaad

- Dolnoserbski

- डोटेली

- ཇོང་ཁ

- Eesti

- Ελληνικά

- Emiliàn e rumagnòl

- Эрзянь

- Español

- Esperanto

- Estremeñu

- Euskara

- Eʋegbe

- فارسی

- Fiji Hindi

- Føroyskt

- Français

- Frysk

- Fulfulde

- Furlan

- Gaeilge

- Gaelg

- Gagauz

- Gàidhlig

- Galego

- ГӀалгӀай

- 贛語

- Gĩkũyũ

- گیلکی

- ગુજરાતી

- 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌹𐍃𐌺

- गोंयची कोंकणी / Gõychi Konknni

- Gungbe

- 客家語/Hak-kâ-ngî

- Хальмг

- 한국어

- Hausa

- Hawaiʻi

- Հայերեն

- हिन्दी

- Hornjoserbsce

- Hrvatski

- Bahasa Hulontalo

- Ido

- Igbo

- Ilokano

- বিষ্ণুপ্রিয়া মণিপুরী

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Interlingua

- Interlingue

- ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ / inuktitut

- Iñupiatun

- Ирон

- IsiXhosa

- IsiZulu

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- עברית

- Jawa

- Kabɩyɛ

- ಕನ್ನಡ

- Kapampangan

- Къарачай-малкъар

- ქართული

- कॉशुर / کٲشُر

- Kaszëbsczi

- Қазақша

- Kernowek

- Ikinyarwanda

- Ikirundi

- Kiswahili

- Коми

- Kongo

- Kotava

- Kreyòl ayisyen

- Kriyòl gwiyannen

- Kurdî

- Кыргызча

- Кырык мары

- Ladin

- Ladino

- Лакку

- ລາວ

- Latgaļu

- Latina

- Latviešu

- Lëtzebuergesch

- Лезги

- Lietuvių

- Li Niha

- Ligure

- Limburgs

- Lingála

- Lingua Franca Nova

- Livvinkarjala

- La .lojban.

- Luganda

- Lombard

- Magyar

- Madhurâ

- मैथिली

- Македонски

- Malagasy

- മലയാളം

- Malti

- Māori

- मराठी

- მარგალური

- مصرى

- ဘာသာမန်

- مازِرونی

- Bahasa Melayu

- ꯃꯤꯇꯩ ꯂꯣꯟ

- Minangkabau

- 閩東語 / Mìng-dĕ̤ng-ngṳ̄

- Mirandés

- Мокшень

- Монгол

- မြန်မာဘာသာ

- Na Vosa Vakaviti

- Nederlands

- Nedersaksies

- नेपाली

- नेपाल भाषा

- 日本語

- Napulitano

- ߒߞߏ

- Нохчийн

- Nordfriisk

- Norfuk / Pitkern

- Norsk bokmål

- Norsk nynorsk

- Nouormand

- Novial

- Occitan

- Олык марий

- ଓଡ଼ିଆ

- Oromoo

- Oʻzbekcha / ўзбекча

- ਪੰਜਾਬੀ

- पालि

- Pälzisch

- Pangasinan

- Pangcah

- پنجابی

- ပအိုဝ်ႏဘာႏသာႏ

- Papiamentu

- پښتو

- Patois

- Перем коми

- ភាសាខ្មែរ

- Picard

- Piemontèis

- Tok Pisin

- Plattdüütsch

- Polski

- Ποντιακά

- Português

- Qaraqalpaqsha

- Qırımtatarca

- Reo tahiti

- Ripoarisch

- Română

- Romani čhib

- Rumantsch

- Runa Simi

- Русиньскый

- Русский

- Саха тыла

- Sakizaya

- Gagana Samoa

- संस्कृतम्

- Sängö

- ᱥᱟᱱᱛᱟᱲᱤ

- سرائیکی

- Sardu

- Scots

- Seediq

- Seeltersk

- Sesotho

- Sesotho sa Leboa

- Setswana

- Shqip

- Sicilianu

- සිංහල

- Simple English

- سنڌي

- SiSwati

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Словѣньскъ / ⰔⰎⰑⰂⰡⰐⰠⰔⰍⰟ

- Ślůnski

- Soomaaliga

- کوردی

- Sranantongo

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Sunda

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Tagalog

- தமிழ்

- Taclḥit

- Taqbaylit

- Tarandíne

- Татарча / tatarça

- ၽႃႇသႃႇတႆး

- Tayal

- తెలుగు

- Tetun

- ไทย

- Thuɔŋjäŋ

- ትግርኛ

- Тоҷикӣ

- Lea faka-Tonga

- ᏣᎳᎩ

- Tsetsêhestâhese

- Tshivenda

- ತುಳು

- Türkçe

- Türkmençe

- Twi

- Tyap

- Тыва дыл

- Удмурт

- Basa Ugi

- Українська

- اردو

- ئۇيغۇرچە / Uyghurche

- Vahcuengh

- Vèneto

- Vepsän kel’

- Tiếng Việt

- Volapük

- Võro

- Walon

- 文言

- West-Vlams

- Winaray

- Wolof

- 吴语

- Xitsonga

- ייִדיש

- Yorùbá

- 粵語

- Zazaki

- Zeêuws

- Žemaitėška

- 中文

- Tolışi

- ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ ⵜⴰⵏⴰⵡⴰⵢⵜ

Russian Federation Российская Федерация (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Государственный гимн Российской Федерации Gosudarstvennyy gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii " State Anthem of the Russian Federation" | |

Recognized territory of Russia is shown in dark green; claimed and disputed territory is shown in light green.[a] Recognized territory of Russia is shown in dark green; claimed and disputed territory is shown in light green.[a] | |

| Religion |

|

| Government | Federal semi-presidential republic under an authoritarian dictatorship[9][10][11][12] |

| Vladimir Putin | |

| Mikhail Mishustin | |

| Legislature | Federal Assembly |

| Federation Council | |

| State Duma | |

| Formation | |

| 882 | |

| 1157 | |

| 1282 | |

| 16 January 1547 | |

| 2 November 1721 | |

| 15 March 1917 | |

| 30 December 1922 | |

| 12 June 1990 | |

| 12 December 1991 | |

| 12 December 1993 | |

| 8 December 1999 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 17,098,246 km2 (6,601,670 sq mi)[13] (within internationally recognised borders) |

• Water (%) | 13[14] (including swamps) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | ( ₽) (RUB) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 to +12 |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +7 |

| ISO 3166 code | RU |

| Internet TLD | |

Russia,[b] or the Russian Federation,[c] is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the largest country in the world by area, extending across eleven time zones and sharing land borders with fourteen countries.[d] It is the world's ninth-most populous country and Europe's most populous country. The country's capital as well as its largest city is Moscow. Saint Petersburg is Russia's second-largest city and cultural capital. Other major cities in the country include Novosibirsk, Yekaterinburg, Nizhny Novgorod, Chelyabinsk, Krasnoyarsk, Kazan, Krasnodar and Rostov-on-Don.

The

In 1991, the Russian SFSR emerged from the

Internationally, Russia

Etymology

In Russian, the current name of the country, Россия (Rossiya), comes from the

There are several words in Russian which translate to "Russians" in English. The noun and adjective русский, russkiy refers to ethnic Russians. The adjective российский, rossiiskiy denotes Russian citizens regardless of ethnicity. The same applies to the more recently coined noun россиянин, rossiianyn, "Russian" in the sense of citizen of the Russian state.[28][32]

According to the

Later archeological studies mostly confirmed this theory.History

Early history

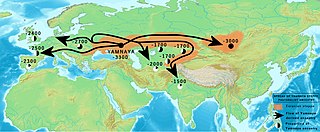

The first human settlement on Russia dates back to the

The first trace of an early modern human in Russia dates back to 45,000 years, in Western Siberia.[41] The discovery of high concentration cultural remains of anatomically modern humans, from at least 40,000 years ago, was found at Kostyonki–Borshchyovo,[42] and at Sungir, dating back to 34,600 years ago—both in western Russia.[43] Humans reached Arctic Russia at least 40,000 years ago, in Mamontovaya Kurya.[44] Ancient North Eurasian populations from Siberia genetically similar to Mal'ta–Buret' culture and Afontova Gora were an important genetic contributor to Ancient Native Americans and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers.[45]

The

In the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, the Gothic kingdom of Oium existed in southern Russia, which was later overrun by Huns. Between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, the Bosporan Kingdom, which was a Hellenistic polity that succeeded the Greek colonies,[55] was also overwhelmed by nomadic invasions led by warlike tribes such as the Huns and Eurasian Avars.[56] The Khazars, who were of Turkic origin, ruled the steppes between the Caucasus in the south, to the east past the Volga river basin, and west as far as Kyiv on the Dnieper river until the 10th century.[57] After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks.[58]

The ancestors of

Kievan Rus'

The establishment of the first East Slavic states in the 9th century coincided with the arrival of

In the 10th to 11th centuries, Kievan Rus' became one of the largest and most prosperous states in Europe. The reigns of

Led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, Novgorodians repelled the invading Swedes in the Battle of the Neva in 1240,[67] as well as the Germanic crusaders in the Battle on the Ice in 1242.[68]

Kievan Rus' finally fell to the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The destruction of Kievan Rus' saw the eventual rise of the

Led by Prince

Tsardom of Russia

In development of the

The death of Ivan's sons marked the end of the ancient

Russia continued its territorial growth through the 17th century, which was the age of the

Imperial Russia

Under Peter the Great, Russia was proclaimed an empire in 1721, and established itself as one of the European great powers. Ruling from 1682 to 1725, Peter defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War (1700–1721), securing Russia's access to the sea and sea trade. In 1703, on the Baltic Sea, Peter founded Saint Petersburg as Russia's new capital. Throughout his rule, sweeping reforms were made, which brought significant Western European cultural influences to Russia.[87] He was succeeded by Catherine I (1725–1727), followed by Peter II (1727–1730), and Anna. The reign of Peter I's daughter Elizabeth in 1741–1762 saw Russia's participation in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). During the conflict, Russian troops overran East Prussia, reaching Berlin.[88] However, upon Elizabeth's death, all these conquests were returned to the Kingdom of Prussia by pro-Prussian Peter III of Russia.[89]

Great power and development of society, sciences and arts

During the

The officers who pursued Napoleon into Western Europe brought ideas of liberalism back to Russia, and attempted to curtail the tsar's powers during the abortive Decembrist revolt of 1825.[101] At the end of the conservative reign of Nicholas I (1825–1855), a zenith period of Russia's power and influence in Europe, was disrupted by defeat in the Crimean War.[102]

Great liberal reforms and capitalism

Nicholas's successor Alexander II (1855–1881) enacted significant changes throughout the country, including the emancipation reform of 1861.[103] These reforms spurred industrialisation, and modernised the Imperial Russian Army, which liberated much of the Balkans from Ottoman rule in the aftermath of the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War.[104] During most of the 19th and early 20th century, Russia and Britain colluded over Afghanistan and its neighbouring territories in Central and South Asia; the rivalry between the two major European empires came to be known as the Great Game.[105]

The late 19th century saw the rise of various socialist movements in Russia. Alexander II was assassinated in 1881 by revolutionary terrorists.[106] The reign of his son Alexander III (1881–1894) was less liberal but more peaceful.[107]

Constitutional monarchy and World War

Under last Russian emperor,

Revolution and civil war

In 1914,

An alternative socialist establishment co-existed, the

The Allied powers launched an unsuccessful military intervention in support of anti-communist forces.[118] In the meantime, both the Bolsheviks and White movement carried out campaigns of deportations and executions against each other, known respectively as the Red Terror and White Terror.[119] By the end of the violent civil war, Russia's economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged, and as many as 10 million perished during the war, mostly civilians.[120] Millions became White émigrés,[121] and the Russian famine of 1921–1922 claimed up to five million victims.[122]

Soviet Union

Command economy and Soviet society

On 30 December 1922, Lenin and his aides

Following

Stalinism and violent modernization

Under Stalin's leadership, the government launched a

World War II and United Nations

The Soviet Union entered World War II on 17 September 1939 with its invasion of Poland,[134] in accordance with a secret protocol within the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany.[135] The Soviet Union later invaded Finland,[136] and occupied and annexed the Baltic states,[137] as well as parts of Romania.[138]: 91–95 On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union,[139] opening the Eastern Front, the largest theater of World War II.[140]: 7

Eventually, some 5 million

The 1941–1945 period of World War II is known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War.[149] The Soviet Union, along with the United States, the United Kingdom and China were considered the Big Four of Allied powers in World War II, and later became the Four Policemen, which was the foundation of the United Nations Security Council.[150]: 27 During the war, Soviet civilian and military death were about 26–27 million,[151] accounting for about half of all World War II casualties.[152]: 295 The Soviet economy and infrastructure suffered massive devastation, which caused the Soviet famine of 1946–1947.[153] However, at the expense of a large sacrifice, the Soviet Union emerged as a global superpower.[154]

Superpower and Cold War

After World War II, according to the Potsdam Conference, the Red Army occupied parts of Eastern and Central Europe, including East Germany and the eastern regions of Austria.[155] Dependent communist governments were installed in the Eastern Bloc satellite states.[156] After becoming the world's second nuclear power,[157] the Soviet Union established the Warsaw Pact alliance,[158] and entered into a struggle for global dominance, known as the Cold War, with the rivalling United States and NATO.[159]

Khrushchev Thaw reforms and economic development

After Stalin's death in 1953 and a short period of collective rule, the new leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and launched the policy of de-Stalinization, releasing many political prisoners from the Gulag labour camps.[160] The general easement of repressive policies became known later as the Khrushchev Thaw.[161] At the same time, Cold War tensions reached its peak when the two rivals clashed over the deployment of the United States Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Soviet missiles in Cuba.[162]

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial

Period of developed socialism or Era of Stagnation

Following the ousting of Khrushchev in 1964, another period of

Perestroika, democratization and Russian sovereignty

From 1985 onwards, the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who sought to enact liberal reforms in the Soviet system, introduced the policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) in an attempt to end the period of economic stagnation and to democratise the government.[168] This, however, led to the rise of strong nationalist and separatist movements across the country.[169] Prior to 1991, the Soviet economy was the world's second-largest, but during its final years, it went into a crisis.[170]

By 1991, economic and political turmoil began to boil over as the

Independent Russian Federation

Transition to a market economy and political crises

The economic and political collapse of the Soviet Union led Russia into a deep and prolonged depression. During and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, wide-ranging reforms including

In late 1993, tensions between Yeltsin and the Russian parliament culminated in a constitutional crisis which ended violently through military force. During the crisis, Yeltsin was backed by Western governments, and over 100 people were killed.[184]

Modern liberal constitution, international cooperation and economic stabilization

In December, a

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia assumed responsibility for settling the latter's external debts.[189] In 1992, most consumer price controls were eliminated, causing extreme inflation and significantly devaluing the rouble.[190] High budget deficits coupled with increasing capital flight and inability to pay back debts, caused the 1998 Russian financial crisis, which resulted in a further GDP decline.[191]

Movement towards a modernized economy, political centralization and democratic backsliding

On 31 December 1999, president Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned,[192] handing the post to the recently appointed prime minister and his chosen successor, Vladimir Putin.[193] Putin then won the 2000 presidential election,[194] and defeated the Chechen insurgency in the Second Chechen War.[195]

Putin won a

Following a

Invasion of Ukraine

In early 2014, following

In June 2023, the Wagner Group, a private military contractor fighting for Russia in Ukraine, declared an open rebellion against the Russian Ministry of Defense, capturing Rostov-on-Don, before beginning a march on Moscow. However, after negotiations between Wagner and the Belarusian government, the rebellion was called off.[220][221]

Geography

Russia's vast landmass stretches over the easternmost part of Europe and the northernmost part of Asia.[222] It spans the northernmost edge of Eurasia; and has the world's fourth-longest coastline, of over 37,653 km (23,396 mi).[f][224] Russia lies between latitudes 41° and 82° N, and longitudes 19° E and 169° W, extending some 9,000 km (5,600 mi) east to west, and 2,500 to 4,000 km (1,600 to 2,500 mi) north to south.[225] Russia, by landmass, is larger than three continents,[g] and has the same surface area as Pluto.[226]

Russia has nine major mountain ranges, and they are found along the

Russia, as one of the world's only three countries

Russia, home of over 100,000 rivers,

Climate

The size of Russia and the remoteness of many of its areas from the sea result in the dominance of the humid continental climate throughout most of the country, except for the tundra and the extreme southwest. Mountain ranges in the south and east obstruct the flow of warm air masses from the Indian and Pacific oceans, while the European Plain spanning its west and north opens it to influence from the Atlantic and Arctic oceans.[239] Most of northwest Russia and Siberia have a subarctic climate, with extremely severe winters in the inner regions of northeast Siberia (mostly Sakha, where the Northern Pole of Cold is located with the record low temperature of −71.2 °C or −96.2 °F),[232] and more moderate winters elsewhere. Russia's vast coastline along the Arctic Ocean and the Russian Arctic islands have a polar climate.[239]

The coastal part of Krasnodar Krai on the Black Sea, most notably Sochi, and some coastal and interior strips of the North Caucasus possess a humid subtropical climate with mild and wet winters.[239] In many regions of East Siberia and the Russian Far East, winter is dry compared to summer; while other parts of the country experience more even precipitation across seasons. Winter precipitation in most parts of the country usually falls as snow. The westernmost parts of Kaliningrad Oblast and some parts in the south of Krasnodar Krai and the North Caucasus have an oceanic climate.[239] The region along the Lower Volga and Caspian Sea coast, as well as some southernmost slivers of Siberia, possess a semi-arid climate.[240]

Throughout much of the territory, there are only two distinct seasons, winter and summer; as spring and autumn are usually brief.

Biodiversity

Russia, owing to its gigantic size, has diverse ecosystems, including polar deserts, tundra, forest tundra, taiga, mixed and broadleaf forest, forest steppe, steppe, semi-desert, and subtropics.[244] About half of Russia's territory is forested,[11] and it has the world's largest area of forest,[245] which sequester some of the world's highest amounts of carbon dioxide.[245][246]

Russian biodiversity includes 12,500 species of

Russia's entirely natural ecosystems are conserved in nearly 15,000 specially protected natural territories of various statuses, occupying more than 10% of the country's total area.

Government and politics

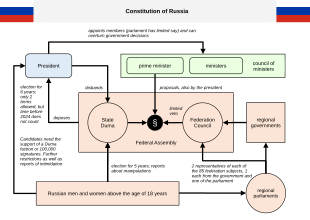

Russia, by 1993 constitution, is a

- Legislative: The bicameral Federal Assembly of Russia, made up of the 450-member State Duma and the 170-member Federation Council,[253] adopts federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse and the power of impeachment of the president.[254]

- Executive: The president is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, and appoints the Government of Russia (Cabinet) and other officers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies.[252] The president may issue decrees of unlimited scope, so long as they do not contradict the constitution or federal law.[255]

- Judiciary: The Constitutional Court, Supreme Court and lower federal courts, whose judges are appointed by the Federation Council on the recommendation of the president,[253] interpret laws and can overturn laws they deem unconstitutional.[256]

The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term and may be elected no more than twice.[257][i] Ministries of the government are composed of the premier and his deputies, ministers, and selected other individuals; all are appointed by the president on the recommendation of the prime minister (whereas the appointment of the latter requires the consent of the State Duma). United Russia is the dominant political party in Russia, and has been described as "big tent" and the "party of power".[259][260] Under the administrations of Vladimir Putin, Russia has experienced democratic backsliding,[261][262] and has become an authoritarian state[12] under a dictatorship,[9][263] with Putin's policies being referred to as Putinism.[264]

Political divisions

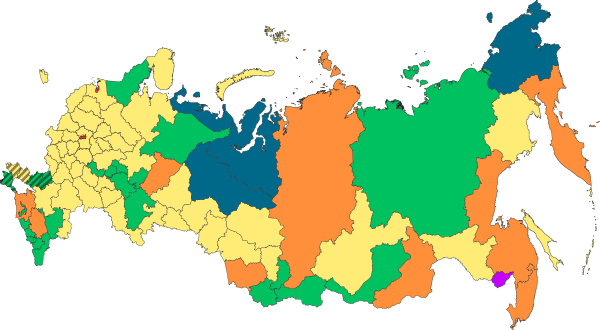

Russia, by 1993 constitution, is a symmetric (with the possibility of an asymmetric configuration) federation. Unlike the Soviet asymmetric model of the RSFSR, where only republics were "subjects of the federation", the current constitution raised the status of other regions to the level of republics and made all regions equal with the title "subject of the federation". The regions of Russia have reserved areas of competence, but no regions have sovereignty, do not have the status of a sovereign state, do not have the right to indicate any sovereignty in their constitutions and do not have the right to secede from the country. The laws of the regions cannot contradict federal laws.[265]

The federal subjects[j] have equal representation—two delegates each—in the Federation Council, the upper house of the Federal Assembly.[266] They do, however, differ in the degree of autonomy they enjoy.[267] The federal districts of Russia were established by Putin in 2000 to facilitate central government control of the federal subjects.[268] Originally seven, currently there are eight federal districts, each headed by an envoy appointed by the president.[269]

| Federal subjects | Governance |

|---|---|

46 oblasts

|

The most common type of federal subject with a governor and locally elected legislature. Commonly named after their administrative centres.[270] |

22 republics

|

Each is nominally autonomous—home to a specific ethnic minority, and has its own constitution, language, and legislature, but is represented by the federal government in international affairs.[271] |

9 krais

|

For all intents and purposes, krais are legally identical to oblasts. The title "krai" ("frontier" or "territory") is historic, related to geographic (frontier) position in a certain period of history. The current krais are not related to frontiers.[272] |

| Occasionally referred to as "autonomous district", "autonomous area", and "autonomous region", each with a substantial or predominant ethnic minority.[273] | |

| Major cities that function as separate regions (Moscow and Saint Petersburg, as well as Sevastopol in Russian-occupied Ukraine).[274] | |

1 autonomous oblast

|

The only autonomous oblast is the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.[275] |

Foreign relations

Russia had the world's fifth-largest diplomatic network in 2019. It maintains diplomatic relations with 190

Russia maintains close relations with neighbouring Belarus, which is a part of the Union State, a supranational confederation of the two states.[283] Serbia has been a historically close ally of Russia, as both countries share a strong mutual cultural, ethnic, and religious affinity.[284] India is the largest customer of Russian military equipment, and the two countries share a strong strategic and diplomatic relationship since the Soviet era.[285] Russia wields influence across the geopolitically important South Caucasus and Central Asia; and the two regions have been described as Russia's "backyard".[286][287]

In the 21st century Russia has pursued an aggressive foreign policy aimed at securing regional dominance and international influence, as well as increasing domestic support for the government. Military intervention in the

Military

The

Russia is among the five

Human rights

Violations of human rights in Russia have been increasingly reported by leading democracy and human rights groups. In particular, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch say that Russia is not democratic and allows few political rights and civil liberties to its citizens.[309][310]

Since 2004,

Muslims, especially

Russia has introduced several restrictions on LGBT rights, including a 2020 ban on same-sex marriage and the designation of LGBT+ organisations such as the Russian LGBT Network as "foreign agents".[332][333]

Corruption

Russia's autocratic[334] political system has been variously described as a kleptocracy,[335] an oligarchy,[336] and a plutocracy.[337] It was the lowest rated European country in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index for 2023, ranking 141th out of 180 countries.[338] Russia has a long history of corruption, which is seen as a significant problem.[339] It impacts various sectors, including the economy,[340] business,[341] public administration,[342] law enforcement,[343] healthcare,[344][345] education,[346] and the military.[347]

Law and crime

The primary and fundamental statement of laws in Russia is the

Russia has the world's second largest illegal arms trade market, after the United States, is ranked first in Europe and 32nd globally in the Global Organized Crime Index, and is among the countries with the highest number of people in prison.[351][352][353]

Economy

Russia has a

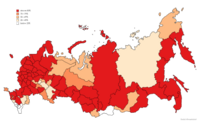

Russia is the world's thirteenth-largest exporter and the 21st-largest importer.[359][360] It relies heavily on revenues from oil and gas-related taxes and export tariffs, which accounted for 45% of Russia's federal budget revenues in January 2022,[361] and up to 60% of its exports in 2019.[362] Russia has one of the lowest levels of external debt among major economies,[363] although its inequality of household income and wealth is one of the highest among developed countries.[364] High regional disparity is also an issue.[365][366]

After over a decade of post-Soviet rapid economic growth, backed by high oil-prices and a surge in foreign exchange reserves and investment,

Transport and energy

Railway transport in Russia is mostly under the control of the state-run Russian Railways. The total length of common-used railway tracks is the world's third-longest, and exceeds 87,000 km (54,100 mi).[373] As of 2016[update], Russia has the world's fifth-largest road network, with 1.5 million km of roads,[374] while its road density is among the world's lowest.[375] Russia's inland waterways are the world's longest, and total 102,000 km (63,380 mi).[376] Among Russia's 1,218 airports,[377] the busiest is Sheremetyevo International Airport in Moscow. Russia's largest port is the Port of Novorossiysk in Krasnodar Krai along the Black Sea.[378]

Russia was widely described as an

In the mid-2000s, the share of the oil and gas sector in GDP was around 20%, and in 2013 it was 20–21% of GDP.[390] The share of oil and gas in Russia's exports (about 50%) and federal budget revenues (about 50%) is large, and the dynamics of Russia's GDP are highly dependent on oil and gas prices,[391] but the share in GDP is much less than 50%. According to the first such comprehensive assessment published by the Russian statistics agency Rosstat in 2021, the maximum total share of the oil and gas sector in Russia's GDP, including extraction, refining, transport, sale of oil and gas, all goods and services used, and all supporting activities, amounts to 19.2% in 2019 and 15.2% in 2020. This is comparable to the share of GDP in Norway and Kazakhstan. It is much lower than the share of GDP in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[392][393][394][395][396]

Russia ratified the

Agriculture and fishery

Russia's agriculture sector contributes about 5% of the country's total GDP, although the sector employs about one-eighth of the total labour force.[403] It has the world's third-largest cultivated area, at 1,265,267 square kilometres (488,522 sq mi). However, due to the harshness of its environment, about 13.1% of its land is agricultural,[11] and only 7.4% of its land is arable.[404] The country's agricultural land is considered part of the "breadbasket" of Europe.[405] More than one-third of the sown area is devoted to fodder crops, and the remaining farmland is devoted to industrial crops, vegetables, and fruits.[403] The main product of Russian farming has always been grain, which occupies considerably more than half of the cropland.[403] Russia is the world's largest exporter of wheat,[406][407] the largest producer of barley and buckwheat, among the largest exporters of maize and sunflower oil, and the leading producer of fertilizer.[408]

Various analysts of climate change adaptation foresee large opportunities for Russian agriculture during the rest of the 21st century as arability increases in Siberia, which would lead to both internal and external migration to the region.[409] Owing to its large coastline along three oceans and twelve marginal seas, Russia maintains the world's sixth-largest fishing industry; capturing nearly 5 million tons of fish in 2018.[410] It is home to the world's finest caviar, the beluga; and produces about one-third of all canned fish, and some one-fourth of the world's total fresh and frozen fish.[403]

Science and technology

Russia spent about 1% of its GDP on

Since the times of

Space exploration

In 1957, the first Earth-orbiting artificial

In 1957,

Russia had 172 active satellites in space in April 2022, the world's third-highest.[442] Between the final flight of the Space Shuttle program in 2011 and the 2020 SpaceX's first crewed mission, Soyuz rockets were the only launch vehicles capable of transporting astronauts to the ISS.[443] Luna 25 launched in August 2023, was the first of the Luna-Glob Moon exploration programme.[444]

Tourism

According to the

Major tourist routes in Russia include a journey around the

Moscow, the nation's cosmopolitan capital and historic core, is a bustling

Demographics

Russia is one of the world's

Since the 1990s, Russia's

However, since 2020, Russia's population gains have been reversed, as excessive deaths from the

Russia is a

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rank

|

Name

|

Federal subject | Pop.

|

Rank

|

Name

|

Federal subject | Pop. |

||

Moscow  Saint Petersburg |

1 | Moscow | Moscow | 13,010,112 | 11 | Rostov-on-Don | Rostov Oblast | 1,142,162 |  Novosibirsk  Yekaterinburg |

| 2 | Saint Petersburg | Saint Petersburg | 5,601,911 | 12 | Omsk | Omsk Oblast | 1,125,695 | ||

| 3 | Novosibirsk | Novosibirsk Oblast | 1,633,595 | 13 | Krasnodar | Krasnodar Krai | 1,099,344 | ||

| 4 | Yekaterinburg | Sverdlovsk Oblast | 1,544,376 | 14 | Voronezh | Voronezh Oblast | 1,057,681 | ||

| 5 | Kazan | Tatarstan | 1,308,660 | 15 | Perm | Perm Krai | 1,034,002 | ||

| 6 | Nizhny Novgorod | Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 1,228,199 | 16 | Volgograd | Volgograd Oblast | 1,028,036 | ||

| 7 | Chelyabinsk | Chelyabinsk Oblast | 1,189,525 | 17 | Saratov | Saratov Oblast | 901,361 | ||

| 8 | Krasnoyarsk | Krasnoyarsk Krai | 1,187,771 | 18 | Tyumen | Tyumen Oblast | 847,488 | ||

| 9 | Samara | Samara Oblast | 1,173,299 | 19 | Tolyatti | Samara Oblast | 684,709 | ||

| 10 | Ufa | Bashkortostan | 1,144,809 | 20 | Barnaul | Altai Krai | 630,877 | ||

Language

Russian is the official and the predominantly spoken language in Russia.[3] It is the most spoken native language in Europe, the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia, as well as the world's most widely spoken Slavic language.[473] Russian is one of two official languages aboard the International Space Station,[474] as well as one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[473]

Russia is a

Religion

Russia is a

Islam is the second-largest religion in Russia, and is the traditional religion among the majority of the

In 2012, the research organisation Sreda, in cooperation with the

Education

Russia has an adult

Russia's

Admission to an institute of higher education is selective and highly competitive:[496] first-degree courses usually take five years.[500] The oldest and largest universities in Russia are Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University.[501] There are ten highly prestigious federal universities across the country. Russia was the world's fifth-leading destination for international students in 2019, hosting roughly 300 thousand.[502]

Health

Russia, by constitution, guarantees free, universal health care for all Russian citizens, through a compulsory state health insurance program.[504] The Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation oversees the Russian public healthcare system, and the sector employs more than two million people. Federal regions also have their own departments of health that oversee local administration. A separate private health insurance plan is needed to access private healthcare in Russia.[505]

Russia spent 5.65% of its GDP on healthcare in 2019.[506] Its healthcare expenditure is notably lower than other developed nations.[507] Russia has one of the world's most female-biased sex ratios, with 0.859 males to every female,[11] due to its high male mortality rate.[508] In 2021, the overall life expectancy in Russia at birth was 70.06 years (65.51 years for males and 74.51 years for females),[509] and it had a very low infant mortality rate (5 per 1,000 live births).[510]

The principal cause of death in Russia are cardiovascular diseases.

Culture

Russian

Russia is home to

Holidays

Russia has eight—public, patriotic, and religious—official holidays.[531] The year starts with New Year's Day on 1 January, soon followed by Russian Orthodox Christmas on 7 January; the two are the country's most popular holidays.[532] Defender of the Fatherland Day, dedicated to men, is celebrated on 23 February.[533] International Women's Day on 8 March, gained momentum in Russia during the Soviet era. The annual celebration of women has become so popular, especially among Russian men, that Moscow's flower vendors often see profits of "15 times" more than other holidays.[534] Spring and Labour Day, originally a Soviet era holiday dedicated to workers, is celebrated on 1 May.[535]

There are many popular non-public holidays. Old New Year is celebrated on 14 January.[540] Maslenitsa is an ancient and popular East Slavic folk holiday.[541] Cosmonautics Day on 12 April, in tribute to the first human trip into space.[542] Two major Christian holidays are Easter and Trinity Sunday.[543]

Art and architecture

Early Russian painting is represented in

In the 1860s, a group of critical

The history of

After the reforms of Peter the Great, Russia's architecture became influenced by Western European styles. The 18th-century taste for

Music

Until the 18th century, music in Russia consisted mainly of church music and folk songs and dances.

During the Soviet era, popular music also produced a number of renowned figures, such as the two balladeers—Vladimir Vysotsky and Bulat Okudzhava,[569] and performers such as Alla Pugacheva.[571] Jazz, even with sanctions from Soviet authorities, flourished and evolved into one of the country's most popular musical forms.[569] By the 1980s, rock music became popular across Russia, and produced bands such as Aria, Aquarium,[572] DDT,[573] and Kino;[574] the latter's leader Viktor Tsoi, was in particular, a gigantic figure.[575] Pop music has continued to flourish in Russia since the 1960s, with globally famous acts such as t.A.T.u.[576]

Literature and philosophy

Russian literature is considered to be among the world's most influential and developed.[518] It can be traced to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in Old East Slavic were composed.[579] By the Age of Enlightenment, literature had grown in importance, with works from Mikhail Lomonosov, Denis Fonvizin, Gavrila Derzhavin, and Nikolay Karamzin.[580] From the early 1830s, during the Golden Age of Russian Poetry, literature underwent an astounding golden age in poetry, prose and drama.[581] Romanticism permitted a flowering of poetic talent: Vasily Zhukovsky and later his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore.[582] Following Pushkin's footsteps, a new generation of poets were born, including Mikhail Lermontov, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, Fyodor Tyutchev and Afanasy Fet.[580]

The first great Russian novelist was

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Russian literature split into Soviet and

Cuisine

Russian cuisine has been formed by climate, cultural and religious traditions, and the vast geography of the nation; and it shares similarities with the cuisines of its neighbouring countries. Crops of

Russia's national non-alcoholic drink is kvass,[621] and the national alcoholic drink is vodka; its production in Russia (and elsewhere) dates back to the 14th century.[622] The country has the world's highest vodka consumption,[623] while beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage.[624] Wine has become increasingly popular in Russia in the 21st century.[625] Tea has been popular in Russia for centuries.[626]

Mass media and cinema

There are 400 news agencies in Russia, among which the largest internationally operating are TASS, RIA Novosti, Sputnik, and Interfax.[628] Television is the most popular medium in Russia.[629] Among the 3,000 licensed radio stations nationwide, notable ones include Radio Rossii, Vesti FM, Echo of Moscow, Radio Mayak, and Russkoye Radio. Of the 16,000 registered newspapers, Argumenty i Fakty, Komsomolskaya Pravda, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Izvestia, and Moskovskij Komsomolets are popular. State-run Channel One and Russia-1 are the leading news channels, while RT is the flagship of Russia's international media operations.[629] Russia has the largest video gaming market in Europe, with over 65 million players nationwide.[630]

Russian and later

The 1960s and 1970s saw a greater variety of artistic styles in Soviet cinema.

Sports

Historically,

See also

Notes

- ^ Crimea, which was annexed by Russia in 2014, remains internationally recognised as a part of Ukraine.[1] Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, which were annexed—though are only partially occupied—in 2022, also remain internationally recognised as a part of Ukraine. The southernmost Kuril Islands have been the subject of a territorial dispute with Japan since their occupation by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II.[2]

- ^ Russian: Россия, romanized: Rossiya, [rɐˈsʲijə]

- ^ Russian: Российская Федерация, tr. Rossiyskaya Federatsiya, IPA: [rɐˈsʲijskəjə fʲɪdʲɪˈratsɨjə]

- partially recognised breakaway states of South Ossetia and Abkhaziathat it occupies in Georgia.

- Russian apartment bombings, the Moscow theater hostage crisis, and the Beslan school siege

- ^ Russia has an additional 850 km (530 mi) of coastline along the Caspian Sea, which is the world's largest inland body of water, and has been variously classified as a sea or a lake.[223]

- ^ Russia, by land area, is larger than the continents of Australia, Antarctica, and Europe; although it covers a large part of the latter itself. Its land area could be roughly compared to that of South America.

- ^ Russia borders, clockwise, to its southwest: the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, to its west: the Baltic Sea, to its north: the Barents Sea (White Sea, Pechora Sea), the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea, and the East Siberian Sea, to its northeast: the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea, and to its southeast: the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan.

- ^ In 2020, constitutional amendments were signed into law that limit the president to two terms overall rather than two consecutive terms, with this limit reset for current and previous presidents.[258]

- ^ Including bodies on territory disputed between Russia and Ukraine whose annexation has not been internationally recognised: the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol since the annexation of Crimea in 2014,[1] and territories set up following the Russian annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts in 2022.

- ^ The Sreda Arena Atlas 2012 did not count the populations of two federal subjects of Russia where the majority of the population is Muslim, namely Chechnya and Ingushetia, which together had a population of nearly 2 million, thus the proportion of Muslims was possibly slightly underestimated.[481]

References

- ^ a b Pifer, Steven (17 March 2020). "Crimea: Six years after illegal annexation". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ a b Chapple, Amos (4 January 2019). "The Kurile Islands: Why Russia And Japan Never Made Peace After World War II". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ JSTOR 43669126.

- ^ "What Languages Are Spoken in Russia?". WorldAtlas. 1 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Shevchenko, Nikolay (21 February 2018). "Check out Russia's Kalmykia: The only region in Europe where Buddhism rules the roost". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Передача иконы "Троица" Русской православной церкви" (in Russian). Фонд Общественное Мнение, ФОМ (Public Opinion Foundation). 22 June 2023. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Передача иконы "Троица" Русской православной церкви" (in Russian). Фонд Общественное Мнение, ФОМ (Public Opinion Foundation). 22 June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ OCLC 1026492383.

officially a democratic state with the rule of law, in practice an authoritarian dictatorship

- ^ "Russia: Freedom in the World 2023 Country Report". Freedom House. 9 March 2023. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Russia – The World Factbook". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ JSTOR 48610429.

- ^ "World Statistics Pocketbook 2016 edition" (PDF). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Statistics Division. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "The Russian federation: general characteristics". Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ Including 2,482,450 people living on the annexed Crimean Peninsula Том 1. Численность и размещение населения. Russian Federal State Statistics Service (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Предварительная оценка численности постоянного населения на 1 января 2022 года и в среднем за 2021 год [Preliminary estimated population as of 1 January 2022 and on the average for 2021] (XLS). Russian Federal State Statistics Service (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Russia)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Russian Federation". World Bank. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 2022, archived from the original on 9 January 2021, retrieved 14 October 2022

- from the original on 22 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Kuchkin, V. A. (2014). Русская земля [Russian land]. In Melnikova, E. A.; Petrukhina, V. Ya. (eds.). Древняя Русь в средневековом мире [Old Rus' in the medieval world] (in Russian). Moscow: Institute of General History of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Ladomir. pp. 700–701.

- ISBN 978-0816071135.

- ISBN 978-5-7859-0085-1. Archived from the originalon 14 August 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-631-21849-4.

- ISBN 9780881410082.

- ^ ISBN 978-1538119426.

- ^ ISBN 1855218712.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-15511-3.

- ISBN 978-1118455074.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- S2CID 143597960.

- ISBN 978-90-04-13874-2.

- JSTOR 128848. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ Adrien, C.J. (19 April 2020). "The Swedish Vikings: Who Were the Rus?". Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- .

- ^ Chepalyga, A.L.; Amirkhanov, Kh.A.; Trubikhin, V.M.; Sadchikova, T.A.; Pirogov, A.N.; Taimazov, A.I. (2011). "Geoarchaeology of the earliest paleolithic sites (Oldowan) in the North Caucasus and the East Europe". Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- PMID 30135540.

- S2CID 3101375.

- PMID 25341783.

- (PDF) from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- PMID 28982795.

- S2CID 1986562.

- PMID 24159019.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017). "Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population". Science. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ISSN 2333-9683.

- PMID 25731166.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (10 June 2015). "Nomadic herders left a strong genetic mark on Europeans and Asians". Science. AAAS. Archived from the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ a b Belinskij, Andrej; Härke, Heinrich (1999). "The 'Princess' of Ipatovo". Archeology. 52 (2). Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-32624-7.

- ^ Koryakova, L. "Sintashta-Arkaim Culture". The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "1998 NOVA documentary: "Ice Mummies: Siberian Ice Maiden"". Transcript. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- S2CID 53792952.

- ISBN 978-3-515-07302-8.

- ISBN 978-0-691-11669-3.

- JSTOR 27943361.

- ISBN 0-19-517726-6

- PMID 30902755.

- ISBN 978-0-631-20814-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Curtis, Glenn E. (1998). "Russia – Early History". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ISBN 0-521-36447-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-86403-9.

- ISBN 978-0-88141-008-2.

- ISBN 978-0-415-08396-6.

- ^ ISBN 0140513264.

- ^ "Battle of the Neva". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- JSTOR 24664446.

- ISBN 978-0-253-20445-5. Archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Davies, Brian L. (2014). Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500–1700 (PDF). Routledge. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Curtis, Glenn E. (1998). "Russia – Muscovy". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ISBN 978-1444308426.

- JSTOR 20171136.

- ISBN 978-1317892755.

- JSTOR 4207642.

- JSTOR 24655823.

- JSTOR 44647035.

- ISBN 978-9-004-30401-7.

- JSTOR 41036998.

- S2CID 164176163.

- S2CID 138066784.

- JSTOR 4210028.

- ^ a b "The Russian Discovery of Siberia". Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-58206-429-4.

- ISBN 978-0-9546995-8-1.

- ^ a b Curtis, Glenn E. (1998). "Russia – Early Imperial Russia". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- S2CID 249687838.

- JSTOR 1844479.

- JSTOR 1833615.

- JSTOR 4205010.

- S2CID 143736977.

- JSTOR 41046596.

- JSTOR 1945868.

- JSTOR 40396520.

- ^ "Exploration and Settlement on the Alaskan Coast". PBS. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- JSTOR 126593.

- National Geographic. Archived from the originalon 5 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- JSTOR 4165613.

- S2CID 151713355.

- ^ Grey, Ian (9 September 1973). "The Decembrists: Russia's First Revolutionaries". History Today. Vol. 23, no. 9. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- S2CID 153338264.

- JSTOR 126692.

- S2CID 159687214.

- JSTOR 20040512.

- JSTOR 309128.

- JSTOR 40868293.

- JSTOR 129919.

- JSTOR 127655.

- JSTOR 204825.

- JSTOR 1836520.

- S2CID 143618581.

- ^ a b c Curtis, Glenn E. (1998). "Russia – Revolutions and Civil War". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Edmund (March 1928). "The Last Days of the Romanovs". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- JSTOR 149631.

- JSTOR 650938.

- National Geographic. Archived from the originalon 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- JSTOR 40106089.

- National Geographic. Archived from the originalon 22 February 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "Russian Civil War – Casualties and consequences of the war". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- S2CID 143704019.

- ^ Haller, Francis (8 December 2003). "Famine in Russia: the hidden horrors of 1921". Le Temps. International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- JSTOR 24356607.

- JSTOR 1174124.

- S2CID 248843930.

- JSTOR 151989.

- ^ Bensley, Michael (2014). "Socialism in One Country: A Study of Pragmatism and Ideology in the Soviet 1920s" (PDF). University of Kent. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- JSTOR 41051345.

- JSTOR 151474.

- JSTOR 151700.

- ISBN 978-90-8686-653-3. Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- S2CID 226316468.

- S2CID 26592600.

- S2CID 155068339.

- JSTOR 152247.

- JSTOR 152247.

- JSTOR 126075.

- ISBN 978-0-817-99791-5.

- S2CID 143690841.

- ISBN 978-1-789-12193-3.

- ISBN 978-0-674-66043-4.

- ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- JSTOR 20030251.

- JSTOR 4413752.

- S2CID 162709461.

- JSTOR 125859.

- National Geographic. Archived from the originalon 20 March 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- JSTOR 20029588.

- ^ "Russia's Monumental Tributes To The 'Great Patriotic War'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 8 May 2020. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-231-12239-9.

- PMID 12288331.

- ISBN 978-1-907-67723-6.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (14 April 2010). "The Soviet Union after 1945: Economic Recovery and Political Repression" (PDF). University of Warwick. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ JSTOR j.ctv2t4dn7.14. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Wills, Matthew (6 August 2015). "Potsdam and the Origins of the Cold War". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- S2CID 154309589.

- S2CID 145715873.

- JSTOR 40393859.

- ISBN 978-1-134-24167-5.

- ISBN 978-1-134-28347-7.

- JSTOR 1316131.

- ^ Fuelling, Cody. "To the Brink: Turkish and Cuban Missiles during the Height of the Cold War". International Social Science Review. 93 (1). University of North Georgia. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- National Geographic. 7 July 2021. Archivedfrom the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen (12 April 2021). "Yuri Gagarin: the spaceman who came in from the cold". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- JSTOR 151112.

- JSTOR 40106851.

- JSTOR 2644534.

- JSTOR 41881835.

- S2CID 46642309. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Dahlburg, John-Thor; Marshall, Tyler (7 September 1991). "Independence for Baltic States: Freedom: Moscow formally recognizes Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, ending half a century of control. Soviets to begin talks soon on new relationships with the three nations". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Parks, Michael (19 March 1991). "Vote Backs Gorbachev but Not Convincingly: Soviet Union: His plan to preserve federal unity is supported—but so is Yeltsin's for a Russian presidency". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Remnick, David (14 June 1991). "Yeltsin Elected President of Russia". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- S2CID 145141360.

- ^ Foltynova, Kristyna (1 October 2021). "The Undoing Of The U.S.S.R.: How It Happened". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Watson, Joey (2 January 2019). "The rise of Russia's oligarchs – and their bid for legitimacy". ABC News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- JSTOR 153715.

- JSTOR 2953371.

- JSTOR 2137719.

- JSTOR 3986388.

- JSTOR 48610380.

- JSTOR 153404.

- ^ Goncharenko, Roman (3 October 2018). "Russia's 1993 crisis still shaping Kremlin politics, 25 years on". DW News. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Who Was Who? The Key Players In Russia's Dramatic October 1993 Showdown". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- S2CID 153594637.

- ^ Hockstader, Lee (12 December 1995). "Chechen War Reveals Weakness in Yektsubm Russia's New Democracy". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- JSTOR 26326421.

- ^ "26 years on, Russia set to repay all Soviet Union's foreign debt". The Straits Times. 26 March 2017. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Chiodo, Abbigail J.; Owyang, Michael T. (2002). "A Case Study of a Currency Crisis: The Russian Default of 1998" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. 86 (6). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: 7–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ "Yeltsin resigns". The Guardian. 31 December 1999. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Bohlen, Celestine (1 January 2000). "Yeltsin Resigns: The Overview; Yeltsin Resigns, Naming Putin as Acting President To Run in March Election". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Wines, Mark (27 March 2000). "Election in Russia: The Overview; Putin Wins Russia Vote in First Round, But His Majority Is Less Than Expected". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- S2CID 52248942.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (15 March 2004). "As Expected, Putin Easily Wins a Second Term in Russia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ a b Ellyatt, Holly (11 October 2021). "5 charts show Russia's economic highs and lows under Putin". CNBC. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- JSTOR 24483492.

- ^ Harding, Luke (8 May 2008). "Putin ever present as Medvedev becomes president". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- JSTOR 41428537.

- ISBN 978-90-04-49910-2. Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- OCLC 1190722543.

- ISBN 978-1-324-05119-0.

- ^ "Russian forces launch full-scale invasion of Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Herb, Jeremy; Starr, Barbara; Kaufman, Ellie (24 February 2022). "US orders 7,000 more troops to Europe following Russia's invasion of Ukraine". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Borger, Julian (2 March 2022). "UN votes to condemn Russia's invasion of Ukraine and calls for withdrawal". The Guardian. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b Walsh, Ben (9 March 2022). "The unprecedented American sanctions on Russia, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "The Russian Federation is excluded from the Council of Europe" (Press release). Council of Europe. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ "UN General Assembly votes to suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council". United Nations. 7 April 2022. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "Putin mobilizes more troops for Ukraine, threatens nuclear retaliation and backs annexation of Russian-occupied land". NBC News. 21 September 2022. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Putin announces partial mobilisation and threatens nuclear retaliation in escalation of Ukraine war". The Guardian. 21 September 2022. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ a b Landay, Jonathan (30 September 2022). "Defiant Putin proclaims Ukrainian annexation as military setback looms". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ "European Parliament declares Russia a state sponsor of terrorism". Reuters. 23 November 2022. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Fiedler, Tristan (18 October 2022). "Estonian parliament declares Russia a terrorist state". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "'Terrible toll': Russia's invasion of Ukraine in numbers". Euractiv. 14 February 2023. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ Hussain, Murtaza (9 March 2023). "The War in Ukraine Is Just Getting Started". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say". The New York Times. 18 August 2023. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Putin's War Escalation Is Hastening Demographic Crash for Russia". Bloomberg. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ "Armed rebellion by Wagner chief Prigozhin underscores erosion of Russian legal system". AP News. 7 July 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ "Rebel Russian mercenaries turn back short of Moscow 'to avoid bloodshed'". Reuters. 24 June 2023. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Russia". National Geographic Kids. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Is the Caspian a sea or a lake?". The Economist. 16 August 2018. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Coastline – The World Factbook". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Russia – Land". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Clark, Stuart (28 July 2015). "Pluto: ten things we now know about the dwarf planet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Klyuchevskoy". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ a b Glenn E. Curtis, ed. (1998). "Topography and Drainage". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b "The Ural Mountains". NASA Earth Observatory. NASA. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Europe – Land". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

The lowest terrain in Europe, virtually lacking relief, stands at the head of the Caspian Sea; there the Caspian Depression reaches some 95 feet (29 metres) below sea level.

- ^ Glenn E. Curtis, ed. (1998). "Global Position and Boundaries". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Russia". The Arctic Institute – Center for Circumpolar Security Studies. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Aziz, Ziryan (28 February 2020). "Island hopping in Russia: Sakhalin, Kuril Islands and Kamchatka Peninsula". Euronews. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Diomede Islands – Russia". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Lake Baikal – A Touchstone for Global Change and Rift Studies". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 14 February 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ "Total renewable water resources". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-300-25604-8.

- ^ "Russia's Largest Rivers From the Amur to the Volga". The Moscow Times. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Glenn E. Curtis, ed. (1998). "Climate". Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- PMID 30375988.

- S2CID 128960702.

- ^ "Putin urges authorities to take action as wildfires engulf Siberia". euronews. 10 May 2022. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Why Russia's thawing permafrost is a global problem". NPR. 22 January 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Russian Federation – Main Details". Convention on Biological Diversity. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Beth (23 March 2021). "Will Russia's Forests Be an Asset or an Obstacle in Climate Fight?". Yale University. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- PMID 34140583.

- ^ "Species richness of Russia". REC. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Russian Federation". UNESCO. June 2017. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- National Geographic. 11 January 2017. Archived from the originalon 3 March 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ISBN 978-3-319-67193-2. Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- PMID 33293507.

- ^ a b "The Constitution of the Russian Federation". (Article 80, § 1). Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85109-781-4.

- ^ "Chapter 5. The Federal Assembly | The Constitution of the Russian Federation". www.constitution.ru. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-107-04079-3. Archivedfrom the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Chapter 7. Judicial Power | The Constitution of the Russian Federation". www.constitution.ru. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Russian Federation". (Article 81, § 3). Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Putin strongly backed in controversial Russian reform vote". BBC. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- S2CID 153495141.

- JSTOR 4624765.

- ISBN 978-1-136-99200-1. Archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Kiyan, Olga (9 April 2020). "Russia & Democratic Backsliding: The Future of Putinism". Harvard International Review. Harvard International Relations Council. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- hdl:10419/256753. Archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- OCLC 1022076734.

- ^ "Постановление Конституционного Суда РФ от 07.06.2000 N 10-П "По делу о проверке конституционности отдельных положений Конституции Республики Алтай и Федерального закона "Об общих принципах организации законодательных (представительных) и исполнительных органов государственной власти субъектов Российской Федерации" | ГАРАНТ". base.garant.ru. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Chapter 5. The Federal Assembly". Constitution of Russia. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- JSTOR 24675138.

- S2CID 153455573.

- ISBN 978-92-823-8022-2. Archived(PDF) from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- S2CID 145259594.

- ISBN 978-0-7656-0559-7.

- JSTOR 210882.

- JSTOR 20433998.

- (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- S2CID 132962208.

- ^ "Global Diplomacy Index – Country Rank". Lowy Institute. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- S2CID 143792013.

- JSTOR 26367728.

- JSTOR 43580687.

- ^ "What is the Collective Security Treaty Organisation?". The Economist. 6 January 2022. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (21 July 2015). "Russia's 'Pivot to Asia' and the SCO". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- S2CID 54682547.

- S2CID 153926665.

- JSTOR 40202977.

- ^ Tamkin, Emily (8 July 2020). "Why India and Russia Are Going to Stay Friends". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- JSTOR 26326394.

- JSTOR 24590931.

The Central Asian states have been dependent on Russia since they gained independence in 1991, not just in economic and energy terms, but also militarily and politically.

- S2CID 231985182.

- ^ "Ukraine cuts diplomatic ties with Russia after invasion". Al Jazeera. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

Ukraine has cut all diplomatic ties with Russia after President Vladimir Putin authorised an all-out invasion of Ukraine by land, air and sea.

- JSTOR 48573515.

- JSTOR 26270816.

- ^ Baev, Pavel (May 2021). "Russia and Turkey: Strategic Partners and Rivals" (PDF). Russie.Nei.Reports. Ifri. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- S2CID 153838744.

- ^ Rumer, Eugene; Sokolsky, Richard; Stronski, Paul (29 March 2021). "Russia in the Arctic – A Critical Examination". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Hunt, Luke (15 October 2021). "Russia Tries to Boost Asia Ties to Counter Indo-Pacific Alliances". Voice of America. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Russia in Africa: What's behind Moscow's push into the continent?". BBC. 7 May 2020. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- JSTOR resrep19825.

- S2CID 199756261.

- ^ Stengel, Richard (20 May 2022). "Putin May Be Winning the Information War Outside of the U.S. and Europe". TIME. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Ryan Bauer and Peter A. Wilson (17 August 2020). "Russia's Su-57 Heavy Fighter Bomber: Is It Really a Fifth-Generation Aircraft?". RAND Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-85743-988-5.

- ^ Nichol, Jim (24 August 2011). "Russian Military Reform and Defense Policy" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Library of Congress. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance". Arms Control Association. August 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Ballistic missile submarines data". Asia Power Index. Lowy Institute. 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-5017-2.

- ^ "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2022" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Bowen, Andrew S. (14 October 2021). "Russian Arms Sales and Defense Industry". Congressional Research Service. Library of Congress. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Shevchenko, Vitaliy (15 March 2022). "Ukraine war: Protester exposes cracks in Kremlin's war message". BBC. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Russian Federation". Amnesty International. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Russia". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Russia: Freedom in the World 2021". Freedom House. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Russia". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Simmons, Ann M. (18 September 2021). "In Russia's Election, Putin's Opponents Are Seeing Double". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (10 June 2021). "In Shadow of Navalny Case, What's Left of the Russian Opposition?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Seddon, Max (13 February 2021). "Russian crackdown brings pro-Navalny protests to halt". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Goncharenko, Roman (21 November 2017). "NGOs in Russia: Battered, but unbowed". DW News. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Yaffa, Joshua (7 September 2021). "The Victims of Putin's Crackdown On The Press". The New Yorker. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Simon, Scott (21 April 2018). "Why Do Russian Journalists Keep Falling?". NPR. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Russia: Growing Internet Isolation, Control, Censorship". Human Rights Watch. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- from the original on 4 July 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Report Says Russia Among 'Worst Violators' Of Religious Freedom". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 21 April 2021.

- ^ Clancy Chassay (19 September 2009). "Russian killings and kidnaps extend dirty war in Ingushetia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022.

- ^ DENIS SOKOLOV (20 August 2016). "Putin's Savage War Against Russia's 'New Muslims'". Newsweek. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ 🇷🇺Ingushetia: A second Chechnya? l People and Power, Al Jazeera, 13 October 2010

- ^ Russia's Invisible War: Crackdown on Salafi Muslims in Dagestan, Human Rights Watch, 17 June 2015, retrieved 17 November 2022

- ^ Associated Press (25 November 2015). "Russian Crackdown on Muslims Fuels Exodus to IS". Voice of America.

- ^ Mairbek Vatchagaev (9 April 2015). "Abuse of Chechens and Ingush in Russian Prisons Creates Legions of Enemies". Jamestown Foundation.

- ^ Marquise Francis (7 April 2022). "What are Russian 'filtration camps'?". Yahoo! News.

- ^ Katie Bo Lillis, Kylie Atwood and Natasha Bertrand (26 May 2022). "Russia is depopulating parts of eastern Ukraine, forcibly removing thousands into remote parts of Russia". CNN. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Weir, Fred (5 December 2022). "In Russia, critiquing the Ukraine war could land you in prison". CSMonitor.com.

- ^ "Russia, Homophobia and the Battle for 'Traditional Values'". Human Rights Watch. 17 May 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (24 November 2022). "Russia passes law banning 'LGBT propaganda' among adults". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ Krastev, Ivan (16 June 2022). "Putin's aggressive autocracy reduces Russian soft power to ashes". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- JSTOR 26532689.

- S2CID 17653502.

- ISBN 978-0-300-24486-1.

- ^ "Corruptions Perceptions Index 2023". Transparency International. 25 January 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "New Reports Highlight Russia's Deep-Seated Culture of Corruption". Voice of America. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Alferova, Ekaterina (26 October 2020). В России предложили создать должность омбудсмена по борьбе с коррупцией [Russia proposed to create the post of Ombudsman for the fight against corruption]. Izvestia Известия (in Russian). Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ "Russia Corruption Report". GAN Integrity. June 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Suhara, Manabu. "Corruption in Russia: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Slavic-Eurasian Research Center. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- JSTOR 29734103.

- ^ Klara Sabirianova Peter; Zelenska, Tetyana (2010). "Corruption in Russian Health Care: The Determinants and Incidence of Bribery" (PDF). Georgia State University. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ "Corruption Pervades Russia's Health System". CBS News. 28 June 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Denisova-Schmidt, Elena; Leontyeva, Elvira; Prytula, Yaroslav (2014). "Corruption at Universities is a Common Disease for Russia and Ukraine". Harvard University. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Cranny-Evans, Sam; Ivshina, Olga (12 May 2022). "Corruption in the Russian Armed Forces". Westminster: Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). Retrieved 6 October 2022.

Corruption in the Russian armed forces, and society in general, has been a long-acknowledged truism.

- ^ Yılmaz, Müleyke Nurefşan İkbal (31 August 2020). "With its Light and Dark Sides; The Unique Semi-Presidential System of the Russian Federation". Küresel Siyaset Merkezi. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- SSRN 1197762. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Butler, William E. (1999). Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. Springer.

- ^ "Criminality in Russia". The Organized Crime Index. 4 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "The Organized Crime Index". The Organized Crime Index. Retrieved 23 May 2023.