SMS Dresden (1907)

SMS Dresden transiting the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Dresden |

| Namesake | City of Dresden |

| Builder | Blohm & Voss , Hamburg |

| Laid down | 1906 |

| Launched | 5 October 1907 |

| Commissioned | 14 November 1908 |

| Fate | Scuttled off Robinson Crusoe Island, 14 March 1915 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Dresden-class cruiser |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 118.3 m (388 ft 1 in) |

| Beam | 13.5 m (44 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 5.53 m (18 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) |

| Range | 3,600 nmi (6,700 km; 4,100 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Dresden ("His Majesty's Ship Dresden")

Dresden spent much of her career overseas. After commissioning, she visited the United States in 1909 during the

Dresden saw action in the Battle of Coronel in November, where she engaged the British cruiser HMS Glasgow, and at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December, where she was the only German warship to escape destruction. She eluded her British pursuers for several more months, until she put into Robinson Crusoe Island in March 1915. Her engines were worn out and she had almost no coal left for her boilers, so the ship's captain contacted the local Chilean authorities to have Dresden interned. She was trapped by British cruisers, including her old opponent Glasgow. The British violated Chilean neutrality and opened fire on the ship in the Battle of Más a Tierra. The Germans scuttled Dresden and the majority of the crew escaped to be interned in Chile for the duration of the war. The wreck remains in the harbor; several artifacts, including her bell and compass, have been returned to Germany.

Design

The 1898 Naval Law authorized the construction of thirty new light cruisers; the program began with the Gazelle class, which was developed into the Bremen and Königsberg classes, both of which incorporated incremental improvements over the course of construction. The primary alteration for the two Dresden-class cruisers, assigned to the 1906 fiscal year, consisted of an additional boiler for the propulsion system to increase engine power.[1][2]

Dresden was 118.3 meters (388 ft 1 in)

Her propulsion system consisted of two Parsons steam turbines, designed to give 14,794 shp (11,032 kW) for a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). The engines were powered by twelve coal-fired water-tube boilers. Dresden carried up to 860 t (850 long tons) of coal, which gave her a range of 3,600 nautical miles (6,700 km; 4,100 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph).[3]

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/40 guns in single mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, six were located amidships, three on either side, and two were placed side by side aft. The guns could engage targets out to 12,200 m (13,300 yd). They were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. The secondary battery comprised eight 5.2 cm (2 in) SK L/55 guns, with 4,000 rounds of ammunition. She was also equipped with two 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes with four torpedoes, mounted on the deck.[3]

The ship was protected by an armored deck that was up to 80 mm (3.1 in) thick. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides, and the guns were protected by 50 mm (2 in) thick shields.[3]

Service history

Dresden was ordered under the contract name

Although Dresden had not completed the required testing, her trials were declared over on 7 September, as she had been ordered to visit the United States.[4] The purpose of the voyage was to represent Germany at the Hudson–Fulton Celebration in New York; Dresden was joined by the protected cruisers Hertha and Victoria Louise and the light cruiser Bremen.[7] Dresden left Wilhelmshaven on 11 September and stopped in Newport, where she met the rest of the ships of the squadron. The ships arrived in New York on 24 September, remained there until 9 October, and arrived back in Germany on 22 October.[4]

Dresden then joined the reconnaissance force for the High Seas Fleet; the following two years consisted of the peacetime routine of squadron exercises, training cruises, and annual fleet exercises. On 16 February 1910, she collided with the light cruiser Königsberg.[4] The collision caused significant damage to Dresden, though no one on either vessel was injured. She made it back to Kiel for repairs,[8] which lasted eight days. Dresden visited Hamburg on 13–17 May that year. From 14 to 20 April 1912, she was temporarily transferred to the Training Squadron, along with the armored cruiser Friedrich Carl and the light cruiser Mainz. For the year 1911–12, Dresden won the Kaiser's Schießpreis (Shooting Prize) for excellent gunnery amongst the light cruisers of the High Seas Fleet. From September 1912 through September 1913, she was commanded by Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Captain) Fritz Lüdecke, who would command the ship again during World War I.[9]

On 6 April 1913, she and the cruiser

The Admiralstab ordered Hertha, which had been on a training cruise for

On 20 July, after the Huerta regime was toppled, Dresden carried Huerta, his vice president, Aureliano Blanquet, and their families to Kingston, Jamaica, where Britain had granted them asylum. Upon arriving in Kingston on the 25th, Köhler learned of the rising political tensions in Europe during the July Crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. By this time, the ship was in need of a refit in Germany, and met with her replacement, Karlsruhe, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, the following day. Lüdecke, who had arrived in command of Karlsruhe, traded places with Köhler aboard Dresden. The Admiralstab initially ordered Dresden to return to Germany for overhaul, but the heightened threat of war by the 31st led the staff to countermand the order, instead instructing Lüdecke to prepare to conduct Handelskrieg (trade war) in the Atlantic.[12][15]

World War I

After receiving the order to remain in the Atlantic, Lüdecke turned his ship south while maintaining radio silence to prevent hostile warships from discovering his vessel. On the night of 4–5 August, he received a radio report informing him of Britain's declaration of war on Germany. He chose the South Atlantic as Dresden's operational area, and steamed to the Brazilian coast. Off the mouth of the

On 26 August, while steaming off the mouth of the

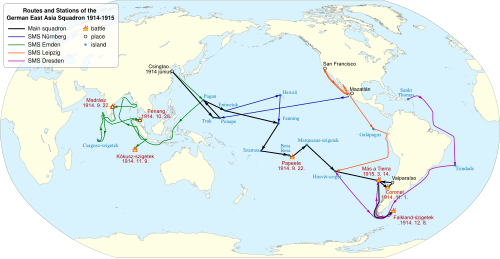

On 18 October, Dresden and the East Asia Squadron, centered on the armored cruisers

Battle of Coronel

Early on the morning of 1 November, Spee took his squadron out of Valparaiso, steaming at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) south toward Coronel. At around 16:00, Leipzig spotted the smoke column from the leading British cruiser. By 16:25, the other two ships had been spotted. The two squadrons slowly closed the distance, until the Germans opened fire at 18:34, at a range of 10,400 m (11,400 yd). The German ships engaged their opposite numbers, with Dresden firing on Otranto. After Dresden's third salvo, Otranto turned away; the Germans claimed a hit that caused a fire,[24] though Otranto reported taking no damage.[25] Following Otranto's departure, Dresden shifted her fire to Glasgow, which was also targeted by Leipzig. The two German cruisers hit their British opponent five times.[26]

At around 19:30, Spee ordered Dresden and Leipzig to launch a torpedo attack against the damaged British armored cruisers. Dresden increased speed to position herself off the British bows, and briefly spotted Glasgow as she was withdrawing, but the British cruiser disappeared in the haze and gathering darkness. Dresden then encountered Leipzig; both ships initially thought the other was hostile. Dresden's crew was loading a torpedo when the two ships confirmed each other's identity. By 22:00, Dresden and the other two light cruisers were deployed in a line that searched unsuccessfully for the British cruisers.[27] Dresden had emerged from the battle completely unscathed.[28]

On 3 November, Spee took Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Nürnberg back to Valparaiso for provisioning and to consult with the Admiralstab. Neutrality laws permitted only three belligerent warships in a port at a given time. Dresden and Leipzig remained with the squadron's colliers in Más a Fuera. Spee returned to Más a Fuera on 6 November, and detached Dresden and Leipzig for a visit to Valparaiso, where they also restocked their supplies. The two cruisers arrived on 12 November, left the following day, and met the rest of the squadron at sea on 18 November. Three days later, the squadron anchored in St. Quentin Bay in the Gulf of Penas, where they coaled. The Royal Navy had deployed Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee's pair of battlecruisers, Invincible and Inflexible, to hunt down the German squadron. They left Britain on 11 November, and arrived in the Falkland Islands on 7 December. There, they joined the armored cruisers Cornwall, Kent, and Carnarvon, and the light cruisers Glasgow and Bristol.[29]

On 26 November, the German East Asia Squadron left St. Quentin Bay, bound for the Atlantic. On 2 December, they caught the Canadian sailing ship Drummuir, which was carrying 2,750 t (2,710 long tons) of high-grade Cardiff coal. The following morning, the Germans anchored off

Battle of the Falkland Islands

On the afternoon of 6 December, the German ships departed Picton Island, bound for the Falklands. On 7 December, they rounded

The British ships set off in pursuit, and by 12:50, Sturdee's two battlecruisers had overtaken the Germans. A minute later, he gave the order to open fire at the trailing German ship, Leipzig. Spee ordered the three small cruisers to try to escape to the south, while he turned back with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in an attempt to hold off the British squadron. Sturdee had foreseen this possibility, and so had ordered his armored and light cruisers to pursue the German light cruisers. The battlecruisers quickly overwhelmed Spee's armored cruisers, and destroyed them with heavy loss of life. Dresden, with her turbine engines, was able to outpace her pursuers, and was the only German warship to escape destruction. Lüdecke decided to take his ship into the islands off South America to keep a steady supply of coal available.[32]

On 9 December, she passed back around Cape Horn to return to the Pacific.[33] That day, she anchored in Sholl Bay, with only 160 t (157 long tons) of coal remaining. Oberleutnant zur See (lieutenant at sea) Wilhelm Canaris convinced the Chilean naval representative for the region to permit Dresden to remain in the area for an extra twenty-four hours so enough coal could be taken aboard to reach Punta Arenas.[34] She arrived there on 12 December, and received 750 t (740 long tons) of coal from a German steamer.[33] The Admiralstab hoped Dresden would be able to break through to the Atlantic and return to Germany, but the poor condition of her engines precluded this. Lüdecke instead decided to attempt to cross the Pacific via Easter Island, the Solomon Islands, and the Dutch East Indies and raid commerce in the Indian Ocean.[35] Dresden took on another 1,600 t (1,575 long tons) of coal on 19 January.[36] On 14 February, Dresden left the islands off the South American coast for the South Pacific. On 27 February, the cruiser captured the British barque Conway Castle south of Más a Tierra.[33] From December to February, the German liner Sierra Cordoba had supplied Dresden and had accompanied her northward to a final coaling at Juan Fernández Islands just before the cruiser was scuttled.[37]

On 8 March, Dresden was drifting in dense fog when lookouts spotted Kent, which also had her engines off, about 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) away. Both ships immediately raised steam, and Dresden escaped after a five-hour chase. The strenuous effort depleted her coal stocks and overtaxed her engines. Lüdecke decided his ship was no longer operational, and determined to have his ship interned to preserve it. The following morning, she put into Más a Fuera, dropping anchor in Cumberland Bay at 8:30. The following day, Lüdecke received by wireless the German Admiralty's permission to let Dresden be interned, and so Lüdecke informed the local Chilean official of his intention to do so.[38][39]

Battle of Más a Tierra

On the morning of 14 March, Kent and Glasgow approached Cumberland Bay; their appearance was relayed back to Dresden by one of her pinnaces, which had been sent to patrol the entrance to the bay. Dresden was unable to maneuver, owing to her fuel shortage, and Lüdecke signaled that his ship was no longer a combatant. The British disregarded this message, as well as a Chilean vessel that approached them as they entered the bay. Glasgow opened fire, in violation of Chile's neutrality; Britain had already informed Chile that British warships would disregard international law if they located Dresden in Chilean territorial waters.[40] Shortly thereafter, Kent joined in the bombardment as well. The German gunners fired off three shots in response, but the guns were quickly knocked out by British gunfire.[41]

Lüdecke sent the signal "Am sending negotiator" to the British warships, and dispatched Canaris in a pinnace; Glasgow continued to bombard the defenseless cruiser. In another attempt to stop the attack, Lüdecke raised the white flag, which prompted Glasgow to cease fire. Canaris came aboard to speak with Captain John Luce; the former strongly protested the latter's violation of Chile's neutrality. Luce simply replied that he had his orders, and demanded an unconditional surrender. Canaris explained that Dresden had already been interned by Chile, and thereafter returned to his ship, which had in the meantime been prepared for scuttling.[40]

At 10:45, the scuttling charge detonated in the bow and exploded the forward ammunition magazines. The bow was badly mangled; in about half an hour, the ship had taken on enough water to sink. As it struck the sea floor, the bow was torn from the rest of the ship, which rolled over to starboard. As the rest of the hull settled below the waves, a second scuttling charge exploded in the ship's engine rooms.[42]

33°38′8″S 78°49′7″W / 33.63556°S 78.81861°W

Aftermath

Most of the ship's crew managed to escape; only eight men were killed in the attack, with another twenty-nine wounded.[43] The British auxiliary cruiser HMS Orama took fifteen severely wounded men to Valparaiso; four of them died.[18] The destruction of his ship had left Lüdecke in shock, and so Canaris took responsibility for the fate of the ship's crew. They remained on the island for five days until two Chilean warships brought a German passenger ship to take the men to Quiriquina Island, where they were interned for the duration of the war. Canaris escaped from the internment camp on 5 August 1915 and reached Germany exactly two months later.[44] On 31 March 1917, a small group of men escaped on the Chilean barque Tinto; the voyage back to Germany lasted 120 days. The rest of the crew did not return to Germany until 1920.[18]

The wreck lies at a depth of 70 meters (230 ft).

In 1965, the ship's compass and several flags were recovered and returned to Germany, where they are held at the German

Notes

Footnotes

- Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

Citations

- ^ Herwig, p. 42.

- ^ Nottelmann, pp. 108–114.

- ^ a b c d Gröner, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 269.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Koop & Schmolke, p. 104.

- ^ Levine & Panetta, p. 51.

- New York Times. 17 February 1910. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 268–269.

- New York Times. 7 April 1913. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Lenz, p. 183.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 270.

- New York Times. 16 April 1914. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Lenz, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Delgado, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Mueller, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c d e Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 271.

- ^ a b Mueller, p. 12.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Halpern, p. 80.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 273.

- ^ Staff, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Staff, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Massie, p. 242.

- ^ Staff, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Staff, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Mueller, p. 14.

- ^ Staff, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Staff, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Staff, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Staff, pp. 65, 68–73.

- ^ a b c Staff, p. 80.

- ^ Mueller, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Mueller, p. 16.

- ^ Extracts, pp. 412–438.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 272.

- ^ Mueller, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Mueller, p. 17.

- ^ Delgado, p. 168.

- ^ Delgado, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Staff, p. 81.

- ^ Mueller, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b "Underwater Cultural Heritage from World War I". unesco.org. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ Delgado, p. 175.

- ^ Delgado, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Delgado, p. 180.

- ^ Gröner, p. 106.

References

- Delgado, James P. (2004). Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-926685-60-1.

- "Extracts from the Log of the Dresden with Comments". The Naval Review. 3. Swanmore: Naval Society. 1915. OCLC 876873409.

- ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Herwig, Holger (1980). "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 2. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8364-9743-5.

- Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2004). Kleine Kreuzer 1903–1918 (Bremen- bis Cöln-Klasse) (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 3-7637-6252-3.

- Lenz, Lawrence (2008). Power and Policy: America's First Steps to Superpower, 1889–1922. New York: Algora Pub. ISBN 978-0-87586-665-9.

- Levine, Edward F. & Panetta, Roger (2009). Hudson–Fulton Celebration of 1909. Charleston: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 978-0-7385-6281-0.

- ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Mueller, Michael (2007). Canaris: The Life and Death of Hitler's Spymaster. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-101-3.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas: German Cruiser Battles, 1914–1918. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-182-6.

- The Naval Review. 52. Swanmore: Naval Society. 1964. ]

Further reading

- ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

- Parker de Bassi, Maria Teresa (1993). Kreuzer Dresden: Odyssee ohne Wiederkehr (in German). Herford: Koehler Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 3-7822-0591-X.

- Perez Ibarra, Martin (2014). Señales del Dresden (in Spanish). Chile: Uqbar Editores. ISBN 978-956-9171-36-9.