SMS Thüringen

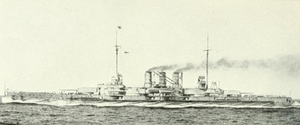

SMS Thüringen, probably before the war

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Thüringen |

| Namesake | Thuringia |

| Builder | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down | 2 November 1908 |

| Launched | 27 November 1909 |

| Commissioned | 1 July 1911 |

| Decommissioned | 16 December 1918 |

| Stricken | 5 November 1919 |

| Fate | Ceded to France in 1920, later used as target ship and sunk. Broken up for scrap, 1923–33 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Helgoland-class battleship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 167.20 m (548 ft 7 in) |

| Beam | 28.50 m (93 ft 6 in) |

| Draft | 8.94 m (29 ft 4 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 20.8 knots (38.5 km/h; 23.9 mph) |

| Range | 5,500 nautical miles (10,190 km; 6,330 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

SMS Thüringen

Along with her three sister ships, Helgoland, Ostfriesland, and Oldenburg, Thüringen participated in all of the major fleet operations of World War I in the North Sea against the British Grand Fleet. This included the Battle of Jutland on 31 May and 1 June 1916, the largest naval battle of the war. Thüringen was involved in the heavy night fighting at Jutland, including the destruction of the armored cruiser HMS Black Prince.[1] The ship also saw action against the Imperial Russian Navy in the Baltic Sea, where she participated in the unsuccessful first incursion into the Gulf of Riga in August 1915.

After the German collapse in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet was interned in

Design

The ship was 167.2 m (548 ft 7 in)

Thüringen was armed with a

.Her main

Service history

Thüringen was ordered by the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) under the provisional name Ersatz Beowulf,

After her commissioning on 1 July 1911, Thüringen conducted sea trials, which were completed by 10 September. On 19 September, she was assigned to I Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet, alongside her sisters.[1] She then went on to conduct individual ship training exercises, which were followed by I Squadron exercises and then fleet maneuvers in November.[8] The annual summer cruise in July and August, which typically went to Norway, was interrupted by the Agadir Crisis. As a result, the cruise only went into the Baltic.[9] Thüringen and the rest of the fleet then fell into a pattern of individual ship, squadron, and full fleet exercises over the next two years.[1] In October 1913, William Michaelis became the ship's commanding officer; he held the post until February 1915.[10]

On 14 July 1914, the annual summer cruise to Norway began.

World War I

Thüringen was present during the first sortie by the German fleet into the North Sea, which took place on 2–3 November 1914. No British forces were encountered during the operation. A second operation followed on 15–16 December.

The

The eight I Squadron ships went into the Baltic on 22 February 1915 for unit training, which lasted until 13 March. Following their return to the North Sea, the ships participated in a series of uneventful fleet sorties on 29–30 March, 17–18 April, 21–22 April, 17–18 May, and 29–30 May. Thüringen and the rest of the fleet then remained in port until 4 August, when I Squadron returned to the Baltic for another round of training maneuvers. From there, the squadron was attached to the naval force that attempted to sweep the

On 23–24 October, the High Seas Fleet undertook its last major offensive operation under the command of Pohl, though it ended without contact with British forces.

Battle of Jutland

Thüringen was present during the fleet operation that resulted in the battle of Jutland which took place on 31 May and 1 June 1916. The German fleet again sought to draw out and isolate a portion of the Grand Fleet and destroy it before the main British fleet could retaliate. During the operation, Thüringen was the second ship in I Division of I Squadron and the tenth ship in the line, directly astern of the squadron flagship Ostfriesland and ahead of another sister Helgoland. I Squadron was the center of the German line, behind the eight König- and Kaiser-class battleships of III Squadron. The six elderly pre-dreadnoughts of III and IV Divisions, II Battle Squadron, formed the rear of the formation.[26]

Shortly before 16:00, the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group encountered the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of David Beatty. The opposing ships began an artillery duel that saw the destruction of

While the leading battleships engaged the British battlecruiser squadron, Thüringen and ten other battleships, too far out of range to attack the British battlecruisers, fired on the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron. Thüringen and Kronprinz engaged the cruiser Dublin, though both ships failed to score a hit.[30] Thüringen fired for eight minutes at ranges of 18,600 to 20,800 yd (17,000 to 19,000 m), expending twenty-nine 30.5 cm shells.[31] The British destroyers Nestor and Nomad, which had been disabled earlier in the engagement, laid directly in the path of the advancing High Seas Fleet.[32] Thüringen and three other battleships destroyed Nestor with their primary and secondary guns while several III Squadron battleships sank Nomad.[33] Shortly after 19:15, the British dreadnought Warspite came into range; Thüringen opened fire at 19:25 with her main and secondary battery guns, at ranges of 10,600 to 11,800 yd (9,700 to 10,800 m). The ship fired twenty-one 30.5 cm and thirty-seven 15 cm shells in the span of five or six minutes, after which Thüringen's gunners lost sight of Warspite, without scoring any hits. They then shifted fire to Malaya.[34] Thüringen fired twenty main battery rounds at Malaya, also unsuccessfully, over seven minutes at a range of 14,100 yd (12,900 m) before conforming to a 180-degree turn ordered by Scheer to disengage from the British fleet.[35]

At around 23:30, the German fleet reorganized into the night-cruising formation. Thüringen was the seventh ship, stationed toward the front of the 24-ship line.

Despite the ferocity of the night fighting, the High Seas Fleet punched through the British destroyer forces and reached

Subsequent operations

On 18 August, Admiral Scheer attempted to repeat the 31 May operation. The two serviceable German battlecruisers (Moltke and Von der Tann), supported by three dreadnoughts, would bombard

On 25–26 September, Thüringen and the rest of I Squadron covered an advance conducted by the second commander of the torpedo-boat flotillas (II Führer der Torpedoboote) to the

Fate

Thüringen and her three sisters were to have taken part in a

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral

Notes

Footnotes

- Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/50 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/50 gun is 50 calibers, meaning that the gun is 50 times as long as its diameter.[4]

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

- ^ The Germans were on Central European Time, which is one hour ahead of UTC, the time zone commonly used in British works.

- ^ The compass can be divided into 32 points, each corresponding to 11.25 degrees. A two-point turn to port would alter the ships' course by 22.5 degrees.

- ^ Derfflinger and Seydlitz had been seriously damaged at the Battle of Jutland, and Lützow had been sunk.[42][43]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Staff (Volume 1), p. 44.

- ^ a b c d Gröner, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Gröner, p. 25.

- ^ Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 146.

- ^ Staff (Volume 1), p. 36.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Staff (Volume 1), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Staff (Volume 1), p. 8.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 230.

- ^ Staff (Volume 1), p. 11.

- ^ Staff (Volume 2), p. 14.

- ^ Heyman, p. xix.

- ^ Staff (Volume 1), pp. 11, 43.

- ^ Garland & Garland, p. 669.

- ^ Herwig, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 38.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 43.

- ^ Halpern, p. 196.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Herwig, p. 161.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 50.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 53.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 54.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 286.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 110.

- ^ Campbell, p. 54.

- ^ Campbell, p. 99.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 114.

- ^ Campbell, p. 101.

- ^ Campbell, p. 154.

- ^ Campbell, p. 155.

- ^ Campbell, p. 275.

- ^ Campbell, p. 290.

- ^ Campbell, p. 293.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 263.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 292.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 277.

- ^ Massie, p. 682.

- ^ Staff (Volume 2), p. 15.

- ^ Massie, p. 683.

- ^ a b Staff (Volume 1), pp. 43, 46.

- ^ a b c d Staff (Volume 1), p. 46.

- ^ Staff (Volume 1), pp. 44, 46.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 281–282.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 282.

- ^ Herwig, p. 252.

- ^ Staff (Volume 1), pp. 26–46.

- ^ Herwig, p. 256.

- ^ Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Garland, Henry B. & Garland, Mary (1986). The Oxford Companion to German Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866139-9.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Heyman, Neil M. (1997). World War I. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29880-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0267-1.

- ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 1: Deutschland, Nassau and Helgoland Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 2: Kaiser, König And Bayern Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-468-8.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective, a New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.