Salem witch trials

- العربية

- Azərbaycanca

- বাংলা

- Беларуская

- Български

- Català

- Čeština

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Gaelg

- Gàidhlig

- 한국어

- Հայերեն

- Hrvatski

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Italiano

- עברית

- ქართული

- Қазақша

- Latina

- Latviešu

- Lingua Franca Nova

- Magyar

- മലയാളം

- مصرى

- Bahasa Melayu

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk bokmål

- Piemontèis

- Português

- Română

- Русский

- Shqip

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Suomi

- Svenska

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- 中文

| Part of a series on |

| Puritans |

|---|

|

|

Crucial themes

|

|

History

|

|

England |

|

America |

|

Elsewhere |

|

Robert Woodford |

|

Continuing movements

|

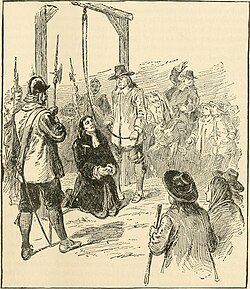

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, nineteen of whom were executed by hanging (fourteen women and five men). One other man, Giles Corey, died under torture after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in jail.[1]

Arrests were made in numerous towns beyond

The episode is one of colonial America's most notorious cases of

At the 300th anniversary events in 1992 to commemorate the victims of the trials, a park was dedicated in Salem and a memorial in Danvers. In 1957, an act passed by the Massachusetts legislature absolved six people,[5] while another one, passed in 2001, absolved five other victims.[6] As of 2004, there was still talk about exonerating all of the victims,[7] though some think that happened in the 18th century as the Massachusetts colonial legislature was asked to reverse the attainders of "George Burroughs and others".[8] In January 2016, the University of Virginia announced its Gallows Hill Project team had determined the execution site in Salem, where the 19 "witches" had been hanged. The city dedicated the Proctor's Ledge Memorial to the victims there in 2017.[9][10]

Background

While witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid-17th century, they continued on the fringes of Europe and in the American Colonies. The events in 1692–1693 in Salem became a brief outburst of a sort of hysteria in the New World, while the practice was already waning in most of Europe.

In 1668, in Against Modern Sadducism,[11] Joseph Glanvill claimed that he could prove the existence of witches and ghosts of the supernatural realm. Glanvill wrote about the "denial of the bodily resurrection, and the [supernatural] spirits."[12]

In his treatise, Glanvill claimed that ingenious men should believe in witches and apparitions; if they doubted the reality of spirits, they not only denied demons but also the almighty God. Glanvill wanted to prove that the supernatural could not be denied; those who did deny apparitions were considered heretics, for it also disproved their beliefs in angels.[12] Works by men such as Glanvill and Cotton Mather tried to prove that "demons were alive."[13]

Accusations

The trials began after a few local women in Salem Village were accused of witchcraft by four young girls, Betty Parris (9), Abigail Williams (11), Ann Putnam Jr. (12), and Elizabeth Hubbard (17).[14] The accusations centered around the concept of "affliction," and the witches accused of having caused physical and mental harm to the girls through witchcraft.[15]

Recorded witchcraft executions in New England

The earliest recorded witchcraft execution was that of

Political context

New England had been settled by religious dissenters seeking to build a Bible-based society according to their own chosen discipline.

A new charter for the enlarged

Local context

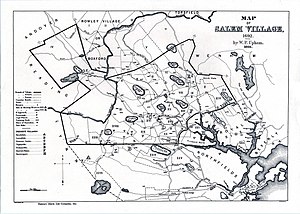

Salem Village (present-day Danvers, Massachusetts) was known for its fractious population, who had many disputes internally and with Salem Town (present-day Salem). Arguments about property lines, grazing rights, and church privileges were rife, and neighbors considered the population as "quarrelsome." In 1672, the villagers had voted to hire a minister of their own, apart from Salem Town. The first two ministers, James Bayley (1673–1679) and George Burroughs (1680–1683), stayed only a few years each, departing after the congregation failed to pay their full rate. (Burroughs was subsequently arrested at the height of the witchcraft hysteria and was hanged as a witch in August 1692.)

Despite the ministers' rights being upheld by the General Court and the parish being admonished, each of the two ministers still chose to leave. The third minister, Deodat Lawson (1684–1688), stayed for a short time, leaving after the church in Salem refused to ordain him—and therefore not over issues with the congregation. The parish disagreed about Salem Village's choice of Samuel Parris as its first ordained minister. On June 18, 1689, the villagers agreed to hire Parris for £66 annually, "one third part in money and the other two third parts in provisions," and use of the parsonage.[26]

On October 10, 1689, however, they raised his benefits, voting to grant him the deed to the parsonage and two acres (0.8 hectares) of land.[27] This conflicted with a 1681 village resolution which stated that "it shall not be lawful for the inhabitants of this village to convey the houses or lands or any other concerns belonging to the Ministry to any particular persons or person: not for any cause by vote or other ways".[28]

Though the prior ministers' fates and the level of contention in Salem Village were valid reasons for caution in accepting the position, Rev. Parris increased the village's divisions by delaying his acceptance. He did not seem able to settle his new parishioners' disputes: by deliberately seeking out "iniquitous behavior" in his congregation and making church members in good standing suffer public penance for small infractions, he contributed significantly to the tension within the village. Its bickering increased unabated. Historian Marion Starkey suggests that, in this atmosphere, serious conflict may have been inevitable.[29]

Religious context

These immigrants, who were mostly constituted of families, established several of the earliest colonies in New England, of which the

In the early 1640s, England erupted in

Gender context

A majority of people accused and convicted of witchcraft were women (about 78%).[34] Overall, the Puritan belief and prevailing New England culture was that women were inherently sinful and more susceptible to damnation than men were.[35] Throughout their daily lives, Puritans, especially Puritan women, actively attempted to thwart attempts by the Devil to overtake them and their souls. Indeed, Puritans held the belief that men and women were equal in the eyes of God, but not in the eyes of the Devil. Women's souls were seen as unprotected in their so-called "weak and vulnerable bodies". Several factors may explain why women were more likely to admit guilt of witchcraft than men. Historian Elizabeth Reis asserts that some likely believed they had truly given in to the Devil, and others might have believed they had done so temporarily. However, because those who confessed were reintegrated into society, some women might have confessed in order to spare their own lives.[35]

Quarrels with neighbors often incited witchcraft allegations. One example of this is Abigail Faulkner, who was accused in 1692. Faulkner admitted she was "angry at what folk said," and the Devil may have temporarily overtaken her, causing harm to her neighbors.[36] Women who did not conform to the norms of Puritan society were more likely to be the target of an accusation, especially those who were unmarried or did not have children.[37]

Publicising witchcraft

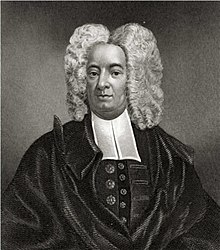

Cotton Mather, a minister of Boston's North Church, was a prolific publisher of pamphlets, including some that expressed his belief in witchcraft. In his book Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (1689), Mather describes his "oracular observations" and how "stupendous witchcraft" had affected the children of Boston mason John Goodwin.[38]

Mather illustrates how the Goodwins' eldest child had been tempted by the devil and had stolen linen from the washerwoman Goody Glover.[39] Glover, of Irish Catholic descent, was characterized as a disagreeable old woman and described by her husband as a witch; this may have been why she was accused of casting spells on the Goodwin children. After the event, four out of six Goodwin children began to have strange fits, or what some people referred to as "the disease of astonishment." The manifestations attributed to the disease quickly became associated with witchcraft. Symptoms included neck and back pains, tongues being drawn from their throats, and loud random outcries; other symptoms included having no control over their bodies such as becoming limber, flapping their arms like birds, or trying to harm others as well as themselves. These symptoms fueled the craze of 1692.[38]

Timeline

Initial events

In Salem Village in February 1692,

The girls complained of being pinched and pricked with pins. A doctor, historically assumed to be William Griggs,[14] could find no physical evidence of any ailment. Other young women in the village began to exhibit similar behaviors. When Lawson preached as a guest in the Salem Village meetinghouse, he was interrupted several times by the outbursts of the afflicted.[42]

The first three people accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting Betty Parris, Abigail Williams, 12-year-old

Sarah Good was a destitute woman accused of witchcraft because of her reputation. At her trial, she was accused of rejecting Puritan ideals of self-control and discipline when she chose to torment and "scorn [children] instead of leading them towards the path of salvation".[46]

Sarah Osborne rarely attended church meetings. She was accused of witchcraft because the Puritans believed that Osborne had her own self-interests in mind following her remarriage to an

Tituba, an

In March, others were accused of witchcraft: Martha Corey, child Dorothy Good, and Rebecca Nurse in Salem Village, and Rachel Clinton in nearby Ipswich. Martha Corey had expressed skepticism about the credibility of the girls' accusations and thus drawn attention. The charges against her and Rebecca Nurse deeply troubled the community because Martha Corey was a full covenanted member of the Church in Salem Village, as was Rebecca Nurse in the Church in Salem Town. If such upstanding people could be witches, the townspeople thought, then anybody could be a witch, and church membership was no protection from accusation. Dorothy Good, the daughter of Sarah Good, was only four years old but was not exempted from questioning by the magistrates; her answers were construed as a confession that implicated her mother. In Ipswich, Rachel Clinton was arrested for witchcraft at the end of March on independent charges unrelated to the afflictions of the girls in Salem Village.[50]

The initial examinations included physical exams where the accused were examined for unique markings such as moles, birth marks that were commonly believed to be associated with the Devil's influence. It was thought that those markings represented the Devil drinking the accused women's blood.[51]

Accusations and examinations before local magistrates

When

Within a week, Giles Corey (Martha's husband and a covenanted church member in Salem Town), Abigail Hobbs, Bridget Bishop, Mary Warren (a servant in the Proctor household and sometime accuser), and Deliverance Hobbs (stepmother of Abigail Hobbs), were arrested and examined. Abigail Hobbs, Mary Warren, and Deliverance Hobbs all confessed and began naming additional people as accomplices. More arrests followed: Sarah Wildes, William Hobbs (husband of Deliverance and father of Abigail), Nehemiah Abbott Jr., Mary Eastey (sister of Cloyce and Nurse), Edward Bishop Jr. and his wife Sarah Bishop, and Mary English.

On April 30, Reverend George Burroughs, Lydia Dustin, Susannah Martin, Dorcas Hoar, Sarah Morey, and Philip English (Mary's husband) were arrested. Nehemiah Abbott Jr. was released because the accusers agreed he was not the person whose specter had afflicted them. Mary Eastey was released for a few days after her initial arrest because the accusers failed to confirm that it was she who had afflicted them; she was arrested again when the accusers reconsidered. In May, accusations continued to pour in, but some of the suspects began to evade apprehension. Multiple warrants were issued before John Willard and Elizabeth Colson were apprehended; George Jacobs Jr. and Daniel Andrews were not caught. Until this point, all the proceedings were investigative, but on May 27, 1692, William Phips ordered the establishment of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties to prosecute the cases of those in jail. Warrants were issued for more people. Sarah Osborne, one of the first three persons accused, died in jail on May 10, 1692.

Warrants were issued for 36 more people, with examinations continuing to take place in Salem Village:

Cotton Mather wrote to one of the judges,

[D]o not lay more stress on pure spectral evidence than it will bear ... It is very certain that the Devils have sometimes represented the Shapes of persons not only innocent, but also very virtuous. Though I believe that the just God then ordinarily provides a way for the speedy vindication of the persons thus abused.[55]

Formal prosecution: The Court of Oyer and Terminer

The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk. Bridget Bishop's case was the first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her. Bishop was described as not living a Puritan lifestyle, for she wore black clothing and odd costumes, which was against the Puritan code. When she was examined before her trial, Bishop was asked about her coat, which had been awkwardly "cut or torn in two ways".[56]

This, along with her "immoral" lifestyle, affirmed to the jury that Bishop was a witch. She went to trial the same day and was convicted. On June 3, the grand jury endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but they did not go to trial immediately, for reasons which are unclear. Bishop was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

Immediately following this execution, the court adjourned for 20 days (until June 30) while it sought advice from New England's most influential ministers "upon the state of things as they then stood."[57][58] Their collective response came back dated June 15 and composed by Cotton Mather:

- The afflicted state of our poor neighbours, that are now suffering by molestations from the invisible world, we apprehend so deplorable, that we think their condition calls for the utmost help of all persons in their several capacities.

- We cannot but, with all thankfulness, acknowledge the success which the merciful God has given unto the sedulous and assiduous endeavours of our honourable rulers, to detect the abominable witchcrafts which have been committed in the country, humbly praying, that the discovery of those mysterious and mischievous wickednesses may be perfected.

- We judge that, in the prosecution of these and all such witchcrafts, there is need of a very critical and exquisite caution, lest by too much credulity for things received only upon the Devil's authority, there be a door opened for a long train of miserable consequences, and Satan get an advantage over us; for we should not be ignorant of his devices.

- As in complaints upon witchcrafts, there may be matters of inquiry which do not amount unto matters of presumption, and there may be matters of presumption which yet may not be matters of conviction, so it is necessary, that all proceedings thereabout be managed with an exceeding tenderness towards those that may be complained of, especially if they have been persons formerly of an unblemished reputation.

- When the first inquiry is made into the circumstances of such as may lie under the just suspicion of witchcrafts, we could wish that there may be admitted as little as is possible of such noise, company and openness as may too hastily expose them that are examined, and that there may no thing be used as a test for the trial of the suspected, the lawfulness whereof may be doubted among the people of God; but that the directions given by such judicious writers as Perkins and Bernard [be consulted in such a case].

- Presumptions whereupon persons may be committed, and, much more, convictions whereupon persons may be condemned as guilty of witchcrafts, ought certainly to be more considerable than barely the accused person's being represented by a specter unto the afflicted; inasmuch as it is an undoubted and notorious thing, that a demon may, by God's permission, appear, even to ill purposes, in the shape of an innocent, yea, and a virtuous man. Nor can we esteem alterations made in the sufferers, by a look or touch of the accused, to be an infallible evidence of guilt, but frequently liable to be abused by the Devil's legerdemains.

- We know not whether some remarkable affronts given to the Devils by our disbelieving those testimonies whose whole force and strength is from them alone, may not put a period unto the progress of the dreadful calamity begun upon us, in the accusations of so many persons, whereof some, we hope, are yet clear from the great transgression laid unto their charge.

- Nevertheless, we cannot but humbly recommend unto the government, the speedy and vigorous prosecution of such as have rendered themselves obnoxious, according to the direction given in the laws of God, and the wholesome statutes of the English nation, for the detection of witchcrafts.

Thomas Hutchinson sums the letter, "The two first and the last sections of this advice took away the force of all the others, and the prosecutions went on with more vigor than before." (Reprinting the letter years later in Magnalia, Cotton Mather left out these "two first and the last" sections.) Major Nathaniel Saltonstall, Esq., resigned from the court on or about June 16, presumably dissatisfied with the letter and that it had not outright barred the admission of spectral evidence. According to Upham, Saltonstall deserves the credit for "being the only public man of his day who had the sense or courage to condemn the proceedings, at the start." (chapt. VII) More people were accused, arrested and examined, but now in Salem Town, by former local magistrates John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney, who had become judges of the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Suspect Roger Toothaker died in prison on June 16, 1692.

From June 30 through early July, grand juries endorsed indictments against Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Proctor, John Proctor, Martha Carrier, Sarah Wildes and Dorcas Hoar. Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin and Sarah Wildes, along with Rebecca Nurse, went to trial at this time, where they were found guilty. All five women were executed by hanging on July 19, 1692. In mid-July, the constable in Andover invited the afflicted girls from Salem Village to visit with his wife to try to determine who was causing her afflictions. Ann Foster, her daughter Mary Lacey Sr., and granddaughter Mary Lacey Jr. all confessed to being witches. Anthony Checkley was appointed by Governor Phips to replace Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney when Newton took an appointment in New Hampshire.

In August, grand juries indicted George Burroughs, Mary Eastey, Martha Corey and George Jacobs Sr. Trial juries convicted Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard, Elizabeth Proctor, and John Proctor. Elizabeth Proctor was given a temporary stay of execution because she was pregnant. On August 19, 1692, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard, and John Proctor were executed:[citation needed]

Mr. Burroughs was carried in a Cart with others, through the streets of Salem, to Execution. When he was upon the Ladder, he made a speech for the clearing of his Innocency, with such Solemn and Serious Expressions as were to the Admiration of all present; his Prayer (which he concluded by repeating the Lord's Prayer) [as witches were not supposed to be able to recite] was so well worded, and uttered with such composedness as such fervency of spirit, as was very Affecting, and drew Tears from many, so that if seemed to some that the spectators would hinder the execution. The accusers said the black Man [Devil] stood and dictated to him. As soon as he was turned off [hanged], Mr. Cotton Mather, being mounted upon a Horse, addressed himself to the People, partly to declare that he [Mr. Burroughs] was no ordained Minister, partly to possess the People of his guilt, saying that the devil often had been transformed into the Angel of Light. And this did somewhat appease the People, and the Executions went on; when he [Mr. Burroughs] was cut down, he was dragged by a Halter to a Hole, or Grave, between the Rocks, about two feet deep; his Shirt and Breeches being pulled off, and an old pair of Trousers of one Executed put on his lower parts: he was so put in, together with Willard and Carrier, that one of his Hands, and his Chin, and a Foot of one of them, was left uncovered.

— Robert Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World.[59]

September 1692

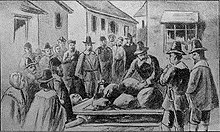

In September, grand juries indicted 18 more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at trial, and was killed by peine forte et dure, a form of torture in which the subject is pressed beneath an increasingly heavy load of stones, in an attempt to make him enter a plea. Four pleaded guilty and 11 others were tried and found guilty.[citation needed]

On September 20, Cotton Mather wrote to Stephen Sewall: "That I may be the more capable to assist in lifting up a standard against the infernal enemy", requesting "a narrative of the evidence given in at the trials of half a dozen, or if you please, a dozen, of the principal witches that have been condemned." On September 22, 1692, eight more persons were executed, "After Execution Mr. Noyes turning him to the Bodies, said, what a sad thing it is to see Eight Firebrands of Hell hanging there."[60]

Dorcas Hoar was given a temporary reprieve, with the support of several ministers, to make a confession of being a witch. Mary Bradbury (aged 77) managed to escape with the help of family and friends. Abigail Faulkner Sr. was pregnant and given a temporary reprieve (some reports from that era say that Abigail's reprieve later became a stay of charges).[citation needed]

Mather quickly completed his account of the trials, Wonders of the Invisible World[61] and it was given to Phips when he returned from the fighting in Maine in early October. Burr says both Phips' letter and Mather's manuscript "must have gone to London by the same ship" in mid-October:[62]

I hereby declare that as soon as I came from fighting ... and understood what danger some of their innocent subjects might be exposed to, if the evidence of the afflicted persons only did prevaile either to the committing or trying any of them, I did before any application was made unto me about it put a stop to the proceedings of the Court and they are now stopt till their Majesties pleasure be known.

— Governor Phips, Boston, October 12, 1692

On October 29, Judge Sewall wrote, "the Court of Oyer and Terminer count themselves thereby dismissed ... asked whether the Court of Oyer and Terminer should sit, expressing some fear of Inconvenience by its fall, [the] Governour said it must fall".[63] Perhaps by coincidence, Governor Phips' own wife, Lady Mary Phips, was among those who had been "called out upon" around this time. After Phips' order, there were no more executions.

Superior Court of Judicature, 1693

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Salem witch trials" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In January 1693, the new Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize and General Gaol [Jail] Delivery convened in Salem, Essex County, again headed by William Stoughton, as Chief Justice, with Anthony Checkley continuing as the Attorney General, and Jonathan Elatson as Clerk of the Court. The first five cases tried in January 1693 were of the five people who had been indicted but not tried in September: Sarah Buckley, Margaret Jacobs, Rebecca Jacobs, Mary Whittredge (or Witheridge) and Job Tookey. All were found not guilty. Grand juries were held for many of those remaining in jail. Charges were dismissed against many, but 16 more people were indicted and tried, three of whom were found guilty: Elizabeth Johnson Jr.,[64] Sarah Wardwell, and Mary Post.[65]

When Stoughton wrote the warrants for the execution of these three and others remaining from the previous court, Governor Phips issued pardons, sparing their lives. In late January/early February, the Court sat again in Charlestown, Middlesex County, and held grand juries and tried five people: Sarah Cole (of Lynn), Lydia Dustin and Sarah Dustin, Mary Taylor and Mary Toothaker. All were found not guilty but were not released until they paid their jail fees. Lydia Dustin died in jail on March 10, 1693.

At the end of April, the Court convened in Boston, Suffolk County, and cleared Capt. John Alden by proclamation. It heard charges against a servant girl, Mary Watkins, for falsely accusing her mistress of witchcraft. In May, the Court convened in Ipswich, Essex County, and held a variety of grand juries. They dismissed charges against all but five people. Susannah Post, Eunice Frye, Mary Bridges Jr., Mary Barker and William Barker Jr. were all found not guilty at trial, finally putting an end to the series of trials and executions.

Legal procedures

Overview

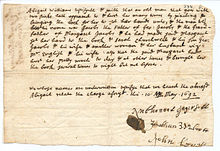

After someone concluded that a loss, illness, or death had been caused by witchcraft, the accuser entered a complaint against the alleged witch with the local magistrates.[66] If the complaint was deemed credible, the magistrates had the person arrested[67] and brought in for a public examination—essentially an interrogation where the magistrates pressed the accused to confess.[68]

If the magistrates at this local level were satisfied that the complaint was well-founded, the prisoner was handed over to be dealt with by a superior court. In 1692, the magistrates opted to wait for the arrival of the new charter and governor, who would establish a Court of

A person could be indicted on charges of afflicting with witchcraft,[70] or for making an unlawful covenant with the Devil.[71] Once indicted, the defendant went to trial, sometimes on the same day, as in the case of the first person indicted and tried on June 2, Bridget Bishop, who was executed eight days later, on June 10, 1692.

There were four execution dates, with one person executed on June 10, 1692,[72] five executed on July 19, 1692 (Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Howe and Sarah Wildes),[73] another five executed on August 19, 1692 (Martha Carrier, John Willard, George Burroughs, George Jacobs Sr., and John Proctor), and eight on September 22, 1692 (Mary Eastey, Martha Corey, Ann Pudeator, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Alice Parker, Wilmot Redd and Margaret Scott).

Several others, including Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor and Abigail Faulkner, were convicted but given temporary reprieves because they were pregnant. Five other women were convicted in 1692, but the death sentence was never carried out: Mary Bradbury (in absentia), Ann Foster (who later died in prison), Mary Lacey Sr. (Foster's daughter), Dorcas Hoar and Abigail Hobbs.

Giles Corey, an 81-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem (called Salem Farms), refused to enter a plea when he came to trial in September. The judges applied an archaic form of punishment called peine forte et dure, in which stones were piled on his chest until he could no longer breathe. After two days of peine fort et dure, Corey died without entering a plea.[74] His refusal to plead is usually explained as a way of preventing his estate from being confiscated by the Crown, but, according to historian Chadwick Hansen, much of Corey's property had already been seized, and he had made a will in prison: "His death was a protest ... against the methods of the court".[75] A contemporary critic of the trials, Robert Calef, wrote, "Giles Corey pleaded not Guilty to his Indictment, but would not put himself upon Tryal by the Jury (they having cleared none upon Tryal) and knowing there would be the same Witnesses against him, rather chose to undergo what Death they would put him to."[76]

As convicted witches, Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey had been excommunicated from their churches and denied proper burials. As soon as the bodies of the accused were cut down from the trees, they were thrown into a shallow grave, and the crowd dispersed. Oral history claims that the families of the dead reclaimed their bodies after dark and buried them in unmarked graves on family property. The record books of the time do not note the deaths of any of those executed. [citation needed]

Spectral evidence

Much, but not all, of the evidence used against the accused was spectral evidence, or the testimony of the afflicted who claimed to see the apparition or the shape of the person who was allegedly afflicting them.[77] The theological dispute that ensued about the use of this evidence was based on whether a person had to give permission to the Devil for his/her shape to be used to afflict. Opponents claimed that the Devil was able to use anyone's shape to afflict people, but the Court contended that the Devil could not use a person's shape without that person's permission; therefore, when the afflicted claimed to see the apparition of a specific person, that was accepted as evidence that the accused had been complicit with the Devil.[78][79]

Cotton Mather's The Wonders of the Invisible World was written with the purpose to show how careful the court was in managing the trials. Unfortunately the work did not get released until after the trials had already ended.[80] In his book, Mather explained how he felt spectral evidence was presumptive and that it alone was not enough to warrant a conviction.[81] Robert Calef, a strong critic of Cotton Mather, stated in his own book titled More Wonders of the Invisible World that by confessing, an accused would not be brought to trial, such as in the cases of Tituba and Dorcas Good.[82][83]

Witch cake

According to a March 27, 1692 entry by Parris in the Records of the Salem-Village Church, a church member and close neighbor of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibley (aunt of Mary Walcott), directed John Indian, a man enslaved by Parris, to make a witch cake.[86] This may have been a superstitious attempt to ward off evil spirits. According to an account attributed to Deodat Lawson ("collected by Deodat Lawson") this happened around March 8, over a week after the first complaints had gone out and three women were arrested. Lawson's account describes this cake "a means to discover witchcraft" and provides other details such as that it was made from rye meal and urine from the afflicted girls and was fed to a dog.[87][88]

In the Church Records, Parris describes speaking with Sibley privately on March 25, 1692, about her "grand error" and accepted her "sorrowful confession." After the main sermon on March 27, and the wider congregation was dismissed, Parris addressed covenanted church-members about it and admonished all the congregation against "going to the Devil for help against the Devil." He stated that while "calamities" that had begun in his own household "it never brake forth to any considerable light, until diabolical means were used, by the making of a cake by my Indian man, who had his direction from this our sister, Mary Sibley." This doesn't seem to square with Lawson's account dating it around March 8. The first complaints were February 29 and the first arrests were March 1.[86]

Traditionally, the allegedly afflicted girls are said to have been entertained by Parris' slave,

Tituba's race has often been described in later accounts as of Carib-Indian or African descent, but contemporary sources describe her only as an "Indian". Research by Elaine Breslaw has suggested that Tituba may have been captured in what is now

Touch test

The most infamous application of the belief in effluvia was the touch test used in Andover during preliminary examinations in September 1692. Parris had explicitly warned his congregation against such examinations. If the accused witch touched the victim while the victim was having a fit, and the fit stopped, observers believed that meant the accused was the person who had afflicted the victim. As several of those accused later recounted:

...we were blindfolded, and our hands were laid upon the afflicted persons, they being in their fits and falling into their fits at our coming into their presence, as they said. Some led us and laid our hands upon them, and then they said they were well and that we were guilty of afflicting them; whereupon we were all seized, as prisoners, by a warrant from the justice of the peace and forthwith carried to Salem.[94]

The Rev. John Hale explained how this supposedly worked: "the Witch by the cast of her eye sends forth a Malefick Venome into the Bewitched to cast him into a fit, and therefore the touch of the hand doth by sympathy cause that venome to return into the Body of the Witch again".[95]

Other evidence

Other evidence included the confessions of the accused; testimony by a confessed witch who identified others as witches; the discovery of poppits (

Primary sources and early discussion

Puritan ministers throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony were exceedingly interested in the trial. Several traveled to Salem in order to gather information about the trial. After witnessing the trials first-hand and gathering accounts, these ministers presented various opinions about the trial starting in 1692.

Deodat Lawson, a former minister in Salem Village, visited Salem Village in March and April 1692. The resulting publication, entitled A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April 1692, was published while the trials were ongoing and relates evidence meant to convict the accused.[41] Simultaneous with Lawson, William Milbourne, a Baptist minister in Boston, publicly petitioned the General Assembly in early June 1692, challenging the use of spectral evidence by the Court. Milbourne had to post £200 bond (equal to £33,310, or about US$42,000 today) or be arrested for "contriving, writing and publishing the said scandalous Papers".[97]

The most famous primary source about the trials is Cotton Mather's Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches, Lately Executed in New-England, printed in October 1692. This text had a tortured path to publication. Initially conceived as a promotion of the trials and a triumphant celebration of Mather's leadership, Mather had to rewrite the text and disclaim personal involvement as suspicion about spectral evidence started to build.[98] Regardless, it was published in both Boston and London, with an introductory letter of endorsement by William Stoughton, the Chief Magistrate. The book included accounts of five trials, with much of the material copied directly from the court records, which were supplied to Mather by Stephen Sewall, a clerk in the court.[99]

Cotton Mather's father, Increase Mather, completed Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits at the same time as Wonders and published it in November 1692. This book was intended to judiciously acknowledge the growing doubts about spectral evidence, while still maintaining the accuracy of Cotton's rewritten, whitewashed text. Like his son, Increase minimized his personal involvement, although he included the full text of his August petition to the Salem court in support of spectral evidence.[100] Judging from the apologetic tone of Cases of Conscience that the moral panic had subsided, Thomas Brattle directly ridiculed the "superstitions" of Salem and Increase's defense of his son in an open letter notable for its openly sarcastic tone.[101]

Samuel Willard, minister of the Third Church in Boston[102] was a onetime strong supporter of the trials and of spectral evidence but became increasingly concerned as the Mathers crushed dissent.[103] Writing anonymously to conceal his dissent, he published a short tract entitled "Some Miscellany Observations On our present Debates respecting Witchcrafts, in a Dialogue Between S. & B." The authors were listed as "P. E. and J. A." (Philip English and John Alden), but the work is generally attributed to Willard. In it, two characters, S (Salem) and B (Boston), discuss the way the proceedings were being conducted, with "B" urging caution about the use of testimony from the afflicted and the confessors, stating, "whatever comes from them is to be suspected; and it is dangerous using or crediting them too far".[104] This book lists its place of publication as Philadelphia, but it is believed to have been secretly printed in Boston.[105]

Aftermath and closure

Although the last trial was held in May 1693, public response to the events continued. In the decades following the trials, survivors and family members (and their supporters) sought to establish the innocence of the individuals who were convicted and to gain compensation. In the following centuries, the descendants of those unjustly accused and condemned have sought to honor their memories. Events in Salem and Danvers in 1992 were used to commemorate the trials. In November 2001, years after the celebration of the 300th anniversary of the trials, the Massachusetts legislature passed an act exonerating all who had been convicted and naming each of the innocent,[106] with the exception of Elizabeth Johnson, who was cleared by the Massachusetts Senate on 26 May 2022, the last conviction to be reversed, after pressure from schoolchildren who discovered the anomaly.[107] The trials have figured in American culture and been explored in numerous works of art, literature and film.

Reversals of attainder and compensation to the survivors

The first indication that public calls for justice were not over occurred in 1695 when Thomas Maule, a noted Quaker, publicly criticized the handling of the trials by the Puritan leaders in Chapter 29 of his book Truth Held Forth and Maintained, expanding on Increase Mather by stating, "it were better that one hundred Witches should live, than that one person be put to death for a witch, which is not a Witch".[108] For publishing this book, Maule was imprisoned twelve months before he was tried and found not guilty.[109]

On December 17, 1696, the General Court ruled that there would be a fast day on January 14, 1697, "referring to the late Tragedy, raised among us by Satan and his Instruments."[110] On that day, Samuel Sewall asked Rev. Samuel Willard to read aloud his apology to the congregation of Boston's South Church, "to take the Blame & Shame" of the "late Commission of Oyer & Terminer at Salem".[111] Thomas Fiske and eleven other trial jurors also asked forgiveness.[112]

From 1693 to 1697, Robert Calef, a "weaver" and a cloth merchant in Boston, collected correspondence, court records and petitions, and other accounts of the trials, and placed them, for contrast, alongside portions of Cotton Mather's Wonders of the Invisible World, under the title More Wonders of the Invisible World,[59]

Calef could not get it published in Boston and he had to take it to London, where it was published in 1700. Scholars of the trials—Hutchinson, Upham, Burr, and even Poole—have relied on Calef's compilation of documents. John Hale, a minister in Beverly who was present at many of the proceedings, had completed his book, A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft in 1697, which was not published until 1702, after his death, and perhaps in response to Calef's book. Expressing regret over the actions taken, Hale admitted, "Such was the darkness of that day, the tortures and lamentations of the afflicted, and the power of former presidents, that we walked in the clouds, and could not see our way."[113]

Various petitions were filed between 1700 and 1703 with the Massachusetts government, demanding that the convictions be formally reversed. Those tried and found guilty were considered dead in the eyes of the law, and with convictions still on the books, those not executed were vulnerable to further accusations. The General Court initially reversed the attainder only for those who had filed petitions,[114] only three people who had been convicted but not executed: Abigail Faulkner Sr., Elizabeth Proctor and Sarah Wardwell.[115][full citation needed] In 1703, another petition was filed,[116] requesting a more equitable settlement for those wrongly accused, but it was not until 1709, when the General Court received a further request, that it took action on this proposal. In May 1709, 22 people who had been convicted of witchcraft, or whose relatives had been convicted of witchcraft, presented the government with a petition in which they demanded both a reversal of attainder and compensation for financial losses.[117]

Repentance was evident within the Salem Village church. Rev. Joseph Green and the members of the church voted on February 14, 1703, after nearly two months of consideration, to reverse the excommunication of Martha Corey.[118] On August 25, 1706, when Ann Putnam Jr., one of the most active accusers, joined the Salem Village church, she publicly asked forgiveness. She claimed that she had not acted out of malice, but had been deluded by Satan into denouncing innocent people, mentioning Rebecca Nurse, in particular,[119] and was accepted for full membership.

On October 17, 1711, the General Court passed a bill reversing the judgment against the twenty-two people listed in the 1709 petition (there were seven additional people who had been convicted but had not signed the petition, but there was no reversal of attainder for them). Two months later, on December 17, 1711, Governor Joseph Dudley authorized monetary compensation to the 22 people in the 1709 petition. The amount of £578 12s was authorized to be divided among the survivors and relatives of those accused, and most of the accounts were settled within a year,[120] but Phillip English's extensive claims were not settled until 1718.[121] Finally, on March 6, 1712, Rev. Nicholas Noyes and members of the Salem church reversed Noyes' earlier excommunications of Rebecca Nurse and Giles Corey.[122]

Memorials

Rebecca Nurse's descendants erected an obelisk-shaped granite memorial in her memory in 1885 on the grounds of the Nurse Homestead in Danvers, with an inscription from John Greenleaf Whittier. In 1892, an additional monument was erected in honor of forty neighbors who signed a petition in support of Nurse.[123]

Not all the condemned had been exonerated in the early 18th century. In 1957, descendants of the six people who had been wrongly convicted and executed but who had not been included in the bill for a reversal of

The 300th anniversary of the trials was marked in 1992 in Salem and Danvers by a variety of events. A memorial park was dedicated in Salem which included stone slab benches inserted in the stone wall of the park for each of those executed in 1692. Speakers at the ceremony in August included playwright Arthur Miller and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel.[125] Danvers erected its own new memorial,[126] and reinterred bones unearthed in the 1950s, assumed to be those of George Jacobs Sr., in a new resting place at the Rebecca Nurse Homestead.[123]

In 1992, The Danvers Tercentennial Committee also persuaded the Massachusetts House of Representatives to issue a resolution honoring those who had died. After extensive efforts by Paula Keene, a Salem schoolteacher, state representatives J. Michael Ruane and Paul Tirone, along with others, issued a bill whereby the names of all those not previously listed were to be added to this resolution. When it was finally signed on October 31, 2001, by Governor Jane Swift, more than 300 years later, all were finally proclaimed innocent.[106][127]

Land in the area was purchased by the city of Salem in 1936 and renamed "Witch Memorial Land" but no memorial was constructed on the site, and popular misconception persisted that the executions had occurred at the top of Gallows Hill.

In literature, media and popular culture

The story of the witchcraft accusations, trials and executions has captured the imagination of writers and artists in the centuries since the event took place. Their earliest impactful use as the basis for an item of popular fiction is the 1828 novel Rachel Dyer by John Neal.[130]

Many interpretations have taken liberties with the facts of the historical episode in the name of literary and/or artistic license—including the popular but false idea that witches in America were burned.[131] As the trials took place at the intersection between a gradually disappearing medieval past and an emerging enlightenment, and dealt with torture and confession, some interpretations draw attention to the boundaries between the medieval and the post-medieval as cultural constructions.[132]

Medical theories about the reported afflictions

The cause of the symptoms of those who claimed affliction continues to be a subject of interest. Various medical and psychological explanations for the observed symptoms have been explored by researchers, including psychological hysteria in response to Indian attacks, convulsive ergotism caused by eating rye bread made from grain infected by the fungus Claviceps purpurea (a natural substance from which LSD is derived),[133] an epidemic of bird-borne encephalitis lethargica, and sleep paralysis to explain the nocturnal attacks alleged by some of the accusers.[134] Some modern historians are less inclined to focus on biological explanations, preferring instead to explore motivations such as jealousy, spite, and a need for attention to explain the behavior.[135]

See also

- List of people executed for witchcraft

- List of people of the Salem witch trials

- Modern witch-hunts

- Salem witchcraft trial (1878)

- Witchcraft accusations against children

- Witch trials in the early modern period

General

References

- ^ Snyder, Heather. "Giles Corey". Salem Witch Trials. Archived from the original on November 22, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ISBN 9780195033786.

- ^ Adams 2008

- ^ Burr, George Lincoln, ed. (1914). Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648–1706. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 195n1.

- ^ "Six Victims of 1692 Salem Witch Trials "Cleared" by Massachusetts..." December 2, 2015. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ "Massachusetts Clears 5 From Salem Witch Trials". The New York Times. November 2, 2001. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Salem may pardon accused witches of 1692". archive.boston.com. The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ISBN 978-0874518528. Archivedfrom the original on September 19, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Writer, Dustin Luca Staff (July 19, 2017). "On 325th anniversary, city dedicates Proctor's Ledge memorial to Salem Witch Trials victims". Salem News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Caroline Newman, "X Marks the Spot" Archived April 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, UVA Today, 16 January 2016, accessed 28 April 2016

- ^ Full title: A blow at modern Sadducism in some philosophical considerations about witchcraft. To which is added, the relation of the fam'd disturbance by the drummer, in the house of Mr. John Mompesson, with some reflections on drollery and atheisme

- ^ a b Glanvill, Joseph. "Essay IV Against modern Sadducism in the matter of Witches and Apparitions", Essay on Several Important Subjects in Philosophy and Religion, 2nd ed., London; printed by Jd for John Baker and H. Mortlock, 1676, pp. 1–4 (in the history 201 course-pack compiled by S. McSheffrey & T. McCormick), p. 26

- ^ 3 Mather, Cotton."Memorable Providence, Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions" Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, law.umkc.edu; accessed June 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c Nichols, Amy. "Salem Witch Trials: Elizabeth Hubbard". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ISBN 9780316387743.

- ^ The Memorial History of Boston: Including Suffolk County, Massachusetts. 1630–1880 (Ticknor and Company (1881), pp. 133–137

- ISBN 978-0199740871.

- ^ The Glorious Revolution in Massachusetts: Selected Documents, 1689–1692 (henceforth cited as Glorious Revolution), Robert Earle Moody and Richard Clive Simmons (eds.), Colonial Society of Massachusetts: Boston, MA, 1988, p. 2.[ISBN missing]

- S2CID 57560166.

- ^ "Letter of Increase Mather to John Richards, 26 October 1691, Glorious Revolution p. 621.

- ^ The Diary of Samuel Sewall, Vol. 1: 1674–1708 (henceforth cited as Sewall Diary), ed. M. Halsey Thomas, Farrar, Straus & Giroux: New York, 1973, p. 287.

- ^ Sewall Diary, p. 288.

- ^ Sewall Diary, p. 291.

- ^ Massachusetts Archives Collections, Governor's Council Executive Records, Vol. 2, 1692, p. 165. Certified copy from the original records at Her Majestie's State Paper Office, London, September 16, 1846.

- ^ Governor's Council Executive Records, Vol. 2, 1692, pp. 174–177.

- ^ Salem Village Record Book (June 18, 1689) Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ Salem Village Record Book, October 10, 1689 Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, etext.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ Salem Village Record Book, December 27, 1681 Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, etext.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ Starkey 1949, pp. 26–28

- ^ Francis J. Bremer and Tom Webster, eds. Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2006)[ISBN missing]

- from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Francis J. Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards (UP New England, 2013)

- ^ Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England society from Bradford to Edwards (2013)

- ^ Reis 1997, p. xvi.

- ^ a b Reis 1997, p. 2.

- ISBN 978-0393317596.

- ISBN 978-0306821202.

- ^ a b Mather, Cotton. Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions. 1689 law.umkc.edu Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine; accessed January 18, 2019.

- ^ Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt, Rosenthal, et al., 2009, p. 15, n2

- ^ John Hale (1697). A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft. Benjamin Elliot. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Deodat Lawson (1692). A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April, 1692. Benjamin Harris. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Deodat Lawson (1692). A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April, 1692. Benjamin Harris. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Breslaw 1996, p. 103.

- ^ See the warrants for their arrests at the University of Virginia archives: 004 0001 Archived August 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine and 033 0001 Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. "The Examination of Sarah Good". Famous Trials. UMKC School of Law. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ "Sarah Osborne House". Salem Witch Museum. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ 7 trans. Montague Summer. Questions VII & XI. "Malleus Maleficarum Part I." sacred-texts.com Archived February 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, June 9, 2010; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Boyer 3

- ^ Virginia.edu Salem witch trials (archives) Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, etext.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ISBN 978-1503608146.

- ^ "Massachusetts Archives: Superior Court of Judicature Witchcraft Trials (January–May 1693), Cases Heard". Salem Witch Trial-Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58979-132-9.

- ^ Charles W. Upham, Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather. A Reply. Archived June 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Morrisania, NY, 1869, Project Gutenberg, gutenberg.org; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-8071-0920-5.

- ^ 1 The Examination of Bridget Bishop, April 19, 1692. "Examination and Evidence of Some Accused Witches in Salem, 1692. law.umkc.edu Archived 2010-12-31 at the Wayback Machine (accessed June 5, 2010)

- ^ Hutchinson, Thomas. "The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692", New England Historical Genealogical Historical Register, Vol. 24, pp. 381–414 (381) October 1870.

- ^ "The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692". May 17, 2008. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^

- ^ Burr, George Lincoln, ed. (1914). Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648–1706. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 369.

- ^ Mather, Cotton (1914). "The Wonders of the Invisible World". In Burr, George Lincoln (ed.). Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648–1706. C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 203–.

- ^ Letters of Governor Phips to the Home Government, 1692–1693, etext.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ Judge Sewall's Diary, I. p. 368.

- ^ "Woman condemned in Salem witch trials on verge of pardon 328 years later". The Guardian. August 19, 2021. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Supreme Judicial Court". Archived from the original on December 15, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ See The Complaint v. Elizabeth Proctor & Sarah Cloyce Archived September 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine for an example of one of the primary sources of this type.

- ^ The Arrest Warrant of Rebecca Nurse Archived September 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ "The Examination of Martha Corey" Archived August 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ For example: "Summons for Witnesses v. Rebecca Nurse" Archived September 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ "Indictment of Sarah Good for Afflicting Sarah Vibber" Archived September 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ "Indictment of Abigail Hobbs for Covenanting" Archived September 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ The Death Warrant of Bridget Bishop Archived September 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed January 9, 2019.

- ^ "Salem Witch Trials". etext.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ Boyer, p. 8.

- ^ Hansen 1969, p. 154

- ^ Robert Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World. 1700, p. 106.

- ^ Kreutter, Sarah (April 2013). "The Devil's Specter: Spectral Evidence and the Salem Witchcraft Crisis". The Spectrum: A Scholars Day Journal. 2: Article 8. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017 – via Digital Commons.

- S2CID 159913824.

- ISBN 978-1467443104. ch.6

- S2CID 159913824.

- S2CID 159913824.

- S2CID 159913824.

- ^ Walker, Rachel (Spring 2001). "Cotton Mather". Salem Witch Trial-Document Archive. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017 – via Documentary Archive and Transcription Project.

- ^ Mather, Cotton (1681–1724). Diary of Cotton Mather. Boston: The Society.

- ^ Bunn & Geiss 1997, p. 7

- ^ a b Salem Village Church Records, pp. 10–12. Archived October 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ GL Burr, Narratives of the Witchcraft Trials, p. 342 Archived January 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Burr, George Lincoln, ed. (1914). Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648–1706. C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 169–190.

- ^ Reis 1997, p. 56

- ^ John Hale (1697). A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft. Benjamin Elliot, Boston. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2007. facsimile of document at the Salem witch trials documentary archive at the University of Virginia.

- ^ Erikson 2005

- ^ Breslaw 1996, p. 13

- ^ Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Province of Massachusetts-Bay, from the Charter of King William and Queen Mary, in 1691, Until the Year 1750, vol. 2, ed. Lawrence Shaw Mayo. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1936); accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Boyer & Nissenbaum 1972, p. 971

- ^ John Hale, A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft, 1696. p. 59. See: [1] Archived 2013-01-20 at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed December 24, 2014.

- from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ National Archives (Great Britain), CO5/785, pp. 336–337.

- S2CID 57558631.

- ^ The Witchcraft Delusion in New England: The wonders of the invisible world, by C. Mather. W. Elliot Woodward. 1866. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- S2CID 57558631.

- ISBN 9780674613010.

- ^ History: Old South Church Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, oldsouth.org; accessed December 24, 2014.

- S2CID 57558631.

- ^ Some Miscellany Archived 2012-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, etext.lib.virginia.edu; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Moore, George (1888). "Notes on the Bibliography of Witchcraft in Massachusetts". Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. New series. 5: 248.

- ^ a b The Boston Globe from Boston, Massachusetts · 31 newspapers.com Archived November 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine; "New Law Exonerates", Boston Globe, 1 November 2001.

- ^ Kole, William J. (May 26, 2022). "329 years later, last Salem 'witch' who wasn't is pardoned". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Virginia.edu Archived December 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine p. 185.

- ^ Cornell University Library Witchcraft Collection, dlxs2.library.cornell.edu; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Robert Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World Part 5, p. 143.

- ^ Francis 2005, pp. 181–182

- ^ Robert Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World Part 5, pp. 144–145.

- ^ As published in George Lincoln Burr's Narratives, p. 525.

- ^ Boyer, P., & Nissenbaum, S. (Eds.). (1977). The Salem witchcraft papers: Verbatim transcripts of the legal documents of the Salem witchcraft outbreak of 1692. New York: Da Capo Press.

- ^ Robinson 2001, pp. xvi–xvii

- ^ Massachusetts Archives Collection, vol. 135, no. 121, p. 108. Massachusetts State Archives. Boston, MA.

- ^ Massachusetts Archives, Vol. 135, p. 112, No. 126.

- ^ Roach 2002, p. 567

- ^ Upham 2000, p. 510

- ^ Essex County Court Archives, vol. 2, no. 136, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

- ^ Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, vol. 9, 1718–1718, Chap. 82 (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1902), pp. 618–619.

- ^ Roach 2002, p. 571

- ^ a b Rebecca Nurse Homestead Archived 2007-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, rebeccanurse.org; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Chapter 145 of the resolves of 1957, Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

- ^ Salem Massachusetts – Salem Witch Trials The Stones: July 10 and July 19, 1692 Archived November 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, salemweb.com; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Salem Village Witchcraft Victims' Memorial, etext.virginia.edu Archived November 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Chapter 122 of the Acts of 2001, Commonwealth of Massachusetts". Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ "Actual Site Of Salem Witch Hangings Discovered". CBS news. January 13, 2016. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Real Salem Witch Hanging Site Was Located". Boston Magazine. January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 82.

- ^ Purkiss, Diane (June 27, 2023). "Witchcraft: Eight Myths and Misconceptions". English Heritage. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ Bernard Rosenthal, "Medievalism and the Salem Witch Trials," in: Medievalism in the Modern World. Essays in Honour of Leslie J. Workman (eds. Richard Utz and Tom Shippey), Turnhout: Brepols, 1998, pp. 61–68.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Secrets of the Dead: The Witches Curse Archived June 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, pbs.org; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Justice at Salem Archived June 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, justiceatsalem.com; accessed December 24, 2014.

- ^ Ana Kucić, Salem Witchcraft Trials: The Perception Of Women In History, Literature And Culture Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, University of Niš, Serbia, 2010, pp. 2–4.

Bibliography

- Adams, Gretchen A. (2008), The Specter of Salem: Remembering the Witch Trials in Nineteenth-Century America, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226005430

- ISBN 978-1-55553-165-2

- Breslaw, Elaine G. (1996), Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies, NYU Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-1307-5

- Bunn, Ivan; Geiss, Gilbert (1997), Trial of Witches: A Seventeenth-Century Witchcraft Prosecution, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-17109-0

- Cooke, William H. (2009), Justice at Salem: Reexamining the Witch Trials, Undertaker Press, ISBN 978-1-59594-322-4, archivedfrom the original on June 13, 2009, retrieved October 23, 2009

- ISBN 978-0-205-42403-0

- Francis, Richard (2005), Judge Sewall's Apology, Harper-Collins

- Glanvill, Joseph. "Essay IV Against modern Sadducism in the matter of Witches and Apparitions" in Essay on several important subjects in philosophy and religion, 2nd Ed, London; printed for John Baker and H. Mortlock, 1676, pp. 1–4 (in the history 201 course-pack compiled by S. McSheffrey & T. McCormick)

- Hansen, Chadwick (1969), Witchcraft at Salem, Brazillier, ISBN 978-0-8076-1137-1

- Mather, Cotton. Memorable Providence, Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions. law.umkc.edu (accessed June 5, 2010)

- Trans. Montague Summer. Questions VII & XI. "Maleus Maleficarum Part I." sacred-texts.com Archived February 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, June 9, 2010.

- Reis, Elizabeth (1997), Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-8611-1

- Roach, Marilynne K. (2002), The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-To-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege, Cooper Square Press, ISBN 978-1-58979-132-9

- Robinson, Enders A. (2001) [1990], The Devil Discovered: Salem Witchcraft 1692, Hippocrene, ISBN 978-1-57766-176-4

- Sears, Donald A. (1978), John Neal, Twayne Publishers, ISBN 080-5-7723-08

- Silverman, Kenneth, ed. (1971), "Letter of Cotton Mather to Stephen Sewall, September 20, 1692", Selected Letters of Cotton Mather, University of Louisiana Press, ISBN 978-0-8071-0920-5

- ISBN 978-0-385-03509-5

- ISBN 978-0-486-40899-6

- The Examination of Bridget Bishop, April 19, 1692. "Examination and Evidence of Some Accused Witches in Salem, 1692. law.umkc.edu (accessed June 5, 2010)

- The Examination of Sarah Good, March 1, 1692. "Examination and Evidence of Some the Accused Witches in Salem, 1692. law.umkc.edu Archived January 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (accessed June 6, 2010)

Further reading

- Aronson, Marc. Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials. Atheneum: New York. 2003. ISBN 1-4169-0315-1

- Baker, Emerson W. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience (2014), Emphasis on the causes

- ISBN 0-674-78526-6

- Brown, David C.. A Guide to the Salem Witchcraft Hysteria of 1692. David C. Brown: Washington Crossing, PA. 1984. ISBN 0-9613415-0-5

- Burns, Margo & Rosenthal, Bernard. "Examination of the Records of the Salem Witch Trials". William and Mary Quarterly, 2008, Vol. 65, No. 3, pp. 401–422.

- ISBN 0-19-517483-6

- Fels, Tony. Switching sides : how a generation of historians lost sympathy for the victims of the Salem witch hunt. Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018 ISBN 1421424371

- Foulds, Diane E. (2010). Death in Salem: The Private Lives Behind the 1692 Witch Hunt.

- Godbeer, Richard. The Devil's Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England. ISBN 0-521-46670-9

- Goss, K. David (2007). The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide. ISBN 978-0-313-32095-8.

- Hale, Rev. John. (1702). A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft.

- ISBN 0-306-81159-6

- Hoffer, Peter Charles. "The Salem Witchcraft Trials: A Legal History". (University of Kansas, 1997). ISBN 0-7006-0859-1

- Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. New York: Vintage, 1987. [This work provides essential background on other witchcraft accusations in 17th century New England.] ISBN 0-393-31759-5

- Lasky, Kathryn. Beyond the Burning Time. Point: New York, 1994 ISBN 0-590-47332-8

- Le Beau, Bryan, F. The Story of the Salem Witch Trials: `We Walked in Clouds and Could Not See Our Way`. Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ. 1998. ISBN 0-13-442542-1

- Levack, Brian P. ed. The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America (2013) excerpt and text search Archived March 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Mappen, Marc, ed. Witches & Historians: Interpretations of Salem. 2nd Edition. Keiger: Malabar, FL. 1996. ISBN 0-88275-653-2

- ISBN 0-14-243733-6

- ISBN 0-375-70690-9

- Ray, Benjamin C. Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692. The University of Virginia Press, 2015. ISBN 9780813937076

- Robbins, Rossell Hope. The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. Crown Publishers Inc., 1959. ISBN 0-600-01183-6

- Robinson, Enders A. Salem Witchcraft and Hawthorne's House of the Seven Gables. Heritage Books: Bowie, MD. 1992. ISBN 1-55613-515-7

- Rosenthal, Bernard. Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692. Cambridge University Press: New York. 1993. ISBN 0-521-55820-4

- Rosenthal, Bernard, ed., et al. Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt. Cambridge University Press: New York. 2009. ISBN 0-521-66166-8

- Sologuk, Sally. Diseases Can Bewitch Durum Millers. Milling Journal. Second quarter 2005.

- Spanos, N.P., J. Gottlieb. "Ergots and Salem village witchcraft: A critical appraisal". Science: 194. 1390–1394:1976.

- Trask, Richard B. `The Devil hath been raised`: A Documentary History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Outbreak of March 1692. Revised edition. Yeoman Press: Danvers, MA. 1997. ISBN 0-9638595-1-X

- Weisman, Richard. Witchcraft, Magic, and Religion in 17th-Century Massachusetts. ISBN 0-87023-494-3

- Wilson, Jennifer M. Witch. Authorhouse, 2005. ISBN 1-4208-2109-1

- Wilson, Lori Lee. The Salem Witch Trials. How History Is Invented series. Lerner: Minneapolis. 1997. ISBN 0-8225-4889-5

- Woolf, Alex. Investigating History Mysteries. Heinemann Library: 2004. ISBN 0-431-16022-8

- Wright, John Hardy. Sorcery in Salem. Arcadia: Portsmouth, NH. 1999. ISBN 0-7385-0084-4

- Preston, VK. "Reproducing Witchcraft: Thou Shalt Not Suffer a Witch to Live". TDR / The Drama Review, 2018, Vol. 62, No. 1, pp. 143–159

- Gagnon, Daniel A., A Salem Witch: The Trial, Execution, and Exoneration of Rebecca Nurse. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2021.ISBN 978-1594163678

External links

- Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692, University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School

- Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, University of Virginia, archive of extensive primary sources, including court papers, maps, interactive maps, and biographies (includes former "Massachusetts Historical Society" link)

- Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II, by Charles Upham, 1867, Project Gutenberg

- SalemWitchTrials.com Essays, biographies of the accused and afflicted, Salem Witch Trials website

- Cotton Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations as Well Historical as Theological, upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils (1693) (online pdf edition), at Digital Commons

- Salem Witch Trials Archived June 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Salem website.

| National | |

|---|---|

| Other | |

| New England |

|

|---|---|

| Mid-Atlantic | |

| Out West |

|

42°31′20″N 70°53′46″W / 42.52222°N 70.89611°W / 42.52222; -70.89611