Saurornithoides

| Saurornithoides | |

|---|---|

| |

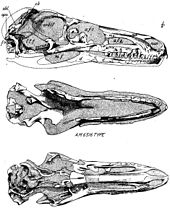

| Holotype skull, AMNH 6516

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Troodontidae |

| Subfamily: | †Troodontinae |

| Genus: | †Saurornithoides Osborn, 1924 |

| Species: | †S. mongoliensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Saurornithoides mongoliensis Osborn, 1924

| |

| Synonyms | |

Saurornithoides ( stems saur~ (lizard), ornith~ (bird) and eides (form), referring to its bird-like skull.

History of discovery

Originally, only one or possibly two individuals of Saurornithoides were known, closely associated within the same layer of the Djadochta Formation of Mongolia. The fossils were found on 9 July 1923 by a Chinese employee of an American Museum of Natural History expedition, Chih. The material contained a single skull and jaw in association, and vertebrae, a partial pelvis, hindlimb and foot associated nearby. More bones were initially included but later shown to belong to Protoceratops. Henry Fairfield Osborn at first intended to name the animal "Ornithoides", the "bird-like one", and in 1924 mentioned this name in a popular publication but without a description so that it remained an invalid nomen nudum.[2] He then formally described the remains in the same year, finding them to be a new genus and species, which he named Saurornithoides mongoliensis. The generic name was chosen because of the bird-like bones of the taxon, which was thought to represent a megalosaurian, translating as "saurian with bird-like rostrum". Saurornithoides was noted to resemble Velociraptor, although more sluggish according to Osborn. The holotype specimen is AMNH 6516.[3] This specimen was the first troodontid skeleton found, though at the time the connection with Troodon, then known only from its teeth, was not realised.[4]

In

In 1993, a juvenile specimen of S. mongoliensis was described.[6] The highly ossified hindlimb suggested that Saurornithoides and other troodontids were well developed at birth and that they probably required little to no parental care.

Several other Saurornithoides species were named, though none of these is today seen as valid. In 1928, baron

Description

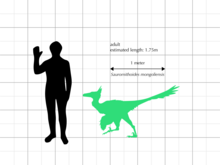

Saurornithoides is a member of the

A juvenile specimen of S. mongoliensis was described in 1993 and gave insights into the life history of the species as well as its relatives;[6] the highly ossified hindlimb suggested that Saurornithoides and other troodontids were well developed at birth and that they probably required little to no parental care.

A revision of the genus in 2009 provided a differential diagnosis, a list of traits in which Saurornithoides differed from certain relevant relatives, especially concentrating on determining its place in the

Classification

Osborn at first placed Saurornithoides in the

The cladogram below follows a 2012 analysis by Turner, Makovicky and Norell.[17]

| Paraves |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6.

- ^ Osborn, Harry F. (1924). "The discovery of an unknown continent". Natural History. 24 (2): 133–149.

- ^ a b Osborn, Harry F. (1924). "Three new Theropoda, Protoceratops zone, Central Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (144): 12.

- ^ hdl:2246/5973.

- ^ a b Rinchen Barsbold (1974). "Saurornithoididae, a new family of small theropod dinosaurs from Central Asia and North America" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 30: 5–22.

- ^ doi:10.1139/e93-193.

- ^ Nopcsa, Franz (1928). "The genera of reptiles". Palaeobiologica. 1: 163–188.

- ^ Nopcsa, Franz (1929). "Addendum: "The genera of reptiles"". Palaeobiologica. 1: 201.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (1982). "Baby dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Lance and Hell Creek formations and a description of a new species of theropod". Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming. 20 (2): 123–134.

- ^ Olshevsky, George (1991). A revision of the parainfraclass Archosauria Cope, 1869, excluding the advanced Crocodylia. Mesozoic Meanderings. Vol. 2.

- ^ Olshevsky, George (1995). "The origin and evolution of the tyrannosaurids (part 1)". Kyoryugaku Saizensen. 9: 92–119.

- ^ Olshevsky, George (1995). "The origin and evolution of the tyrannosaurids (part 2)". Kyoryugaku Saizensen. 10: 75–99.

- ^ Olshevsky, George (2000). An annotated checklist of dinosaur species by continent. Mesozoic Meanderings. Vol. 3.

- S2CID 9743271.

- S2CID 55220748.

- .

- S2CID 83572446.

Bibliography

- Johnson, Jinny (2000). Fantastic Facts About Dinosaurs. ISBN 0-7525-3166-2.

- Lessem, Don (2003). Dinosaurs A to Z. p. 170. ISBN 0-439-16591-1.