Science and technology in Iran

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

|

||||

|

Instruments |

||||

| This is a subseries on philosophy. In order to explore related topics, please visit navigation. | ||||

Science in ancient and Medieval Iran (Persia)

Science in Persia evolved in two main phases separated by the arrival and widespread adoption of Islam in the region.

References to scientific subjects such as natural science and mathematics occur in books written in the

Ancient technology in Iran

The Qanat (a water management system used for irrigation) originated in pre-Achaemenid Iran. The oldest and largest known qanat is in the Iranian city of Gonabad, which, after 2,700 years, still provides drinking and agricultural water to nearly 40,000 people.[5]

Iranian philosophers and inventors may have created the first batteries (sometimes known as the Baghdad Battery) in the Parthian or Sasanian eras. Some have suggested that the batteries may have been used medicinally. Other scientists believe the batteries were used for electroplating—transferring a thin layer of metal to another metal surface—a technique still used today and the focus of a common classroom experiment.[6] However, due to the absence of electrodes on the exterior of the pot, and the lack of records of electroplating at the time, most archaeologists believe it is not a battery, and is more likely a ritual or storage object.[7][8]

Windwheels were developed by the

Mathematics

The first five rows of Khayam-Pascal's triangle

The 9th century mathematician

The

Other Iranian scientists included Abu Abbas Fazl Hatam, Farahani, Omar Ibn Farakhan, Abu Zeid Ahmad Ibn Soheil Balkhi (9th century AD), Abul Vafa Bouzjani, Abu Jaafar Khan,

Medicine

The hospital system was developed in Sassanian Iran; for example, the

Several documents still exist from which the definitions and treatments of the headache in medieval Persia can be ascertained. These documents give detailed and precise clinical information on the different types of headaches. The medieval physicians listed various signs and symptoms, apparent causes, and hygienic and dietary rules for prevention of headaches. The medieval writings are both accurate and vivid, and they provide long lists of substances used in the treatment of headaches. Many of the approaches of physicians in medieval Persia are accepted today; however, still more of them could be of use to modern medicine.[16]

During the 7th century the Achaemenian dynasty was the major advocate of science. Documents indicate that condemned criminals' bodies were dissected and used for medical research during this timeframe[17] In due course, Persians' methods of gathering scientific information would undergo a major change. In the aftermath of the conquest of Islam, Muslim armies destroyed major libraries, and as a result, Persian scholars were deeply concerned as knowledge of the fields of science had been lost. Persians also prohibited the use of human anatomical dissection by Muslim medical practitioners for social and religious reasons.[17] Persian literature was translated into Arabic for approximately two centuries to preserve the surviving Persians literature, which also indirectly served to conserve Persian history.[17]

In the 10th century work of

Later in the 10th century,

After the

An idea of the number of medical works composed in Persian alone may be gathered from Adolf Fonahn's Zur Quellenkunde der Persischen Medizin, published in Leipzig in 1910. The author enumerates over 400 works in the Persian language on medicine, excluding authors such as Avicenna, who wrote in Arabic. Author-historians Meyerhof, Casey Wood, and Hirschberg also have recorded the names of at least 80 oculists who contributed treatises on subjects related to ophthalmology from the beginning of 800 AD to the full flowering of Muslim medical literature in 1300 AD.

Aside from the aforementioned, two other medical works attracted great attention in medieval Europe, namely

Modern academic medicine began in Iran when Joseph Cochran established a medical college in Urmia in 1878. Cochran is often credited for founding Iran's "first contemporary medical college".[19] The website of Urmia University credits Cochran for "lowering the infant mortality rate in the region"[20] and for founding one of Iran's first modern hospitals (Westminster Hospital) in Urmia.

Iran started contributing to modern medical research late in 20th century. Most publications were from pharmacology and pharmacy labs located at a few top universities, most notably Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Astronomy

In 1000 AD,

In the tenth century, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi recorded the first known reference to the Andromeda galaxy, which he called a "little cloud".[21]

In 830, the Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi wrote the first major work of Muslim astronomy. In addition to presenting tables covering the movements of the Sun, Moon and the five planets, Ptolemaic concepts were introduced into Islamic science through this work.[22]

Biology

Medieval Islamic agronomists including Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr described agricultural and horticultural techniques including how to propagate the olive and the date palm, crop rotation of flax with wheat or barley, and companion planting of grape and olive.[24]

Chemistry

The authors of the alchemical texts (c. 850−950) attributed to

The Persian alchemist and physician

Physics

Science policy

The government first set its sights on moving from a resource-based economy to one based on knowledge in its 20-year development plan, Vision 2025, adopted in 2005. This transition became a priority after international sanctions were progressively hardened from 2006 onwards and the oil embargo tightened its grip. In February 2014, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei introduced what he called the '

Vision 2025 challenged policy-makers to look beyond extractive industries to the country's human capital for wealth creation. This led to the adoption of incentive measures to raise the number of university students and academics, on the one hand, and to stimulate problem-solving and industrial research, on the other.[28]

Iran's successive five-year plans aim to realize collectively the goals of Vision 2025. For instance, in order to ensure that 50% of academic research was oriented towards socio-economic needs and problem-solving, the

Vision 2025 fixed a number of targets, including that of raising domestic expenditure on research and development to 4% of GDP by 2025. In 2012, spending stood at 0.33% of GDP.[28]

In 2009, the government adopted a National Master Plan for Science and Education to 2025 which reiterates the goals of Vision 2025. It lays particular stress on developing university research and fostering university–industry ties to promote the commercialization of research results.[28][32][33][34][35][36]

In early 2018, the Science and Technology Department of the Iranian President's Office released a book to review Iran's achievements in various fields of science and technology during 2017. The book, entitled "Science and Technology in Iran: A Brief Review", provides the readers with an overview of the country's 2017 achievements in 13 different fields of science and technology.[37]

Human resources

In line with the goals of Vision 2025, policy-makers have made a concerted effort to increase the number of students and academic researchers. To this end, the government raised its commitment to higher education to 1% of GDP in 2006. After peaking at this level, higher education spending stood at 0.86% of GDP in 2015. Higher education spending has resisted better than public expenditure on education overall. The latter peaked at 4.7% of GDP in 2007 before slipping to 2.9% of GDP in 2015. Vision 2025 fixed a target of raising public expenditure on education to 7% of GDP by 2025.[28]

Student enrollment trends

The result of greater spending on higher education has been a steep rise in tertiary enrollment. Between 2007 and 2013, student rolls swelled from 2.8 million to 4.4 million in the country's public and private universities. Some 45% of students were enrolled in private universities in 2011. There were more women studying than men in 2007, a proportion that has since dropped back slightly to 48%.[28]

Enrollment has progressed in most fields. The most popular in 2013 were social sciences (1.9 million students, of which 1.1 million women) and engineering (1.5 million, of which 373 415 women). Women also made up two-thirds of medical students. One in eight bachelor's students go on to enroll in a master's/PhD programme. This is comparable to the ratio in the Republic of Korea and Thailand (one in seven) and Japan (one in ten).[28]

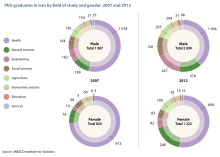

The number of PhD graduates has progressed at a similar pace as university enrollment overall. Natural sciences and engineering have proved increasingly popular among both sexes, even if engineering remains a male-dominated field. In 2012, women made up one-third of PhD graduates, being drawn primarily to health (40% of PhD students), natural sciences (39%), agriculture (33%) and humanities and arts (31%). According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 38% of master's and PhD students were studying science and engineering fields in 2011.[28]

There has been an interesting evolution in the gender balance among PhD students. Whereas the share of female PhD graduates in health remained stable at 38–39% between 2007 and 2012, it rose in all three other broad fields. Most spectacular was the leap in female PhD graduates in agricultural sciences from 4% to 33% but there was also a marked progression in science (from 28% to 39%) and engineering (from 8% to 16% of PhD students). Although data are not readily available on the number of PhD graduates choosing to stay on as faculty, the relatively modest level of domestic research spending would suggest that academic research suffers from inadequate funding.[28]

The Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015) fixed the target of attracting 25 000 foreign students to Iran by 2015. By 2013, there were about 14 000 foreign students attending Iranian universities, most of whom came from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria and Turkey. In a speech delivered at the University of Tehran in October 2014,

scientific evolution will be achieved by criticism [...] and the expression of different ideas. [...] Scientific progress is achieved, if we are related to the world. [...] We have to have a relationship with the world, not only in foreign policy but also with regard to the economy, science and technology. [...] I think it is necessary to invite foreign professors to come to Iran and our professors to go abroad and even to create an English university to be able to attract foreign students.'[28]

One in four Iranian PhD students were studying abroad in 2012 (25.7%). The top destinations were Malaysia, the US, Canada, Australia, UK, France, Sweden and Italy. In 2012, one in seven international students in Malaysia was of Iranian origin. There is a lot of scope for the development of twinning between universities for teaching and research, as well as for student exchanges.[28]

Trends in researchers

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the number of (full-time equivalent) researchers rose from 711 to 736 per million inhabitants between 2009 and 2010. This corresponds to an increase of more than 2 000 researchers, from 52 256 to 54 813. The world average is 1 083 per million inhabitants. One in four (26%) Iranian researchers is a woman, which is close to the world average (28%). In 2008, half of researchers were employed in academia (51.5%), one-third in the government sector (33.6%) and just under one in seven in the business sector (15.0%). Within the business sector, 22% of researchers were women in 2013, the same proportion as in Ireland, Israel, Italy and Norway. The number of firms declaring research activities more than doubled between 2006 and 2011, from 30 935 to 64 642. The increasingly tough sanctions regime oriented the Iranian economy towards the domestic market and, by erecting barriers to foreign imports, encouraged knowledge-based enterprises to localize production.[28]

Research expenditure

Iran's national science budget was about $900 million in 2005 and it had not been subject to any significant increase for the previous 15 years.

The share of private businesses in total national R&D funding according to the same report is very low, being just 14%, as compared with

Funding the transition to a knowledge economy

Vision 2025 foresaw an investment of US$3.7 trillion by 2025 to finance the transition to a knowledge economy. It was intended for one-third of this amount to come from abroad but, so far, FDI has remained elusive. It has contributed less than 1% of GDP since 2006 and just 0.5% of GDP in 2014. Within the country's Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015), a

Much of the US$3.7 trillion earmarked in Vision 2025 is to go towards supporting investment in research and development by knowledge-based firms and the commercialization of research results. A law passed in 2010 provides an appropriate mechanism, the Innovation and Prosperity Fund. According to the fund's president, Behzad Soltani, 4600 billion Iranian rials (circa US$171.4 million) had been allocated to 100 knowledge-based companies by late 2014. Public and private universities wishing to set up private firms may also apply to the fund.[28]

Some 37 industries trade shares on the

The Industrial Development and Renovation Organization (IDRO) controls about 290 state-owned companies. IDRO has set up special purpose companies in each high-tech sector to coordinate investment and business development. These entities are the Life Science Development Company, Information Technology Development Centre, Iran InfoTech Development Company and the Emad Semiconductor Company. In 2010, IDRO set up a capital fund to finance the intermediary stages of product- and technology-based business development within these companies.[28]

Technology parks

As of 2012, Iran had officially 31 science and

| Park's name | Focus area | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Guilan Science and Technology Park | Agro-Food, Biotechnology, Chemistry, Electronics, Environment, ICT, Tourism.[47] | Guilan

|

| Pardis Technology Park | Advanced Engineering (mechanics and automation), Biotechnology, Chemistry, Electronics, ICT, Nano-technology.[47] | 25 km North-East of Tehran |

| Tehran Software and Information Technology Park (planned)[48] | ICT[49] | Tehran |

| Tehran University and Science Technology Park[50] | Tehran | |

| Khorasan Science and Technology Park (Ministry of Science, Research and Technology) | Advanced Engineering, Agro-Food, Chemistry, Electronics, ICT, Services.[47] | Khorasan

|

| Sheikh Bahai Technology Park (Aka "Isfahan Science and Technology Town") | Materials and Metallurgy, Information and Communications Technology, Design & Manufacturing, Automation, Biotechnology, Services.[47] | Isfahan |

| Semnan Province Technology Park | Semnan

| |

| East Azerbaijan Province Technology Park | East Azerbaijan

| |

| Yazd Province Technology Park | Yazd | |

| Mazandaran Science and Technology Park | Mazandaran

| |

| Markazi Province Technology Park | Arak | |

| "Kahkeshan" (Galaxy) Technology Park[citation needed] | Aerospace | Tehran |

| Pars Aero Technology Park[51] | Aerospace & Aviation | Tehran |

| Energy Technology Park (planned)[52] | Energy | — |

Innovation

As of 2004, Iran's national innovation system (NIS) had not experienced a serious entrance to the technology creation phase and mainly exploited the technologies developed by other countries (e.g. in the petrochemicals industry).[53]

In 2016, Iran ranked second in the percentage of graduates in science and engineering in the Global Innovation Index. Iran also ranked fourth in tertiary education, 26 in knowledge creation, 31 in gross percentage of tertiary enrollment, 41 in general infrastructure, 48 in human capital as well as research and 51 in innovation efficiency ratio.[54]

In recent years several

According to the State Registration Organization of Deeds and Properties, a total of 9,570 national inventions were registered in Iran during 2008. Compared with the previous year, there was a 38-percent increase in the number of inventions registered by the organization.[56]Iran was ranked 62nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 67th in 2020.[57][58]

Iran has several funds to support entrepreneurship and innovation:[46]

- Innovation and Flourishing/Prosperity Fund of the Directorate of Science and Technology of the Presidential Office;

- National Researchers and Industrialists Support Fund;

- Nokhbegan Technology Development Institute;

- Nanotechnology Fund;

- Iran Biotech Fund;

- Novin Technology Development Fund;

- Sharif Export Development Research and Technology Fund;

- Support Fund of Researchers and Technologists;

- Payambar Azam (the great prophet) Scientific and Technological Award;

- Student Entrepreneurs Support Fund;

- +6,000 private interest-free funds & 3 Banking in Iran.

Private sector

The 5th Development Plan (2010–15) requires the private sector to communicate research needs to universities so that universities would coordinate research projects in line with these needs, with sharing of expenses by both sides.[52]

Because of its weakness or absence, the support industry makes little contribution to the innovation/technology development activities. Supporting the development of small and medium enterprises in Iran will strengthen greatly the supplier network.[44]

As of 2014, Iran had 930 industrial parks and zones, of which 731 are ready to be ceded to the private sector.[59] The government of Iran has plans for the establishment of 50–60 new industrial parks by the end of the fifth Five-Year Socioeconomic Development Plan (2015).[60]

As of 2016, Iran had nearly 3,000

A 2003-report by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization regarding small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)[63] identified the following impediments to industrial development:

- Lack of monitoring institutions;

- Inefficient banking system;

- Insufficient research & development;

- Shortage of managerial skills;

- Corruption;

- Inefficient taxation;

- Socio-cultural apprehensions;

- Absence of social learning loops;

- Shortcomings in international market awareness necessary for global competition;

- Cumbersome bureaucratic procedures;

- Shortage of skilled labor;

- Lack of intellectual property protection;

- Inadequate social capital, social responsibility and socio-cultural values.

The

Despite these problems, Iran has progressed in various scientific and technological fields, including

Parallel to academic research, several companies have been founded in Iran during last few decades. For example,

In FY 2019, around 5,000 Iranian knowledge-based companies sold $28 billion worth of products or services including pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, polymer and chemical products, and industrial machinery. Among them, 250 companies exported $400 million to Central Asia and all of Iran's direct neighbours.[69]

Science in modern Iran

Theoretical and computational sciences are highly developed in Iran.

Considering the country's

Medical sciences

With over 400 medical research facilities and 76 medical magazine indexes available in the country, Iran is the 19th country in medical research and is set to become the 10th within 10 years (2012).[citation needed] Clinical sciences are invested in highly in Iran. In areas such as rheumatology, hematology, and bone marrow transplantation, Iranian medical scientists publish regularly.[78] The Hematology, Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplantation Research Center (HORC) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Shariati Hospital was established in 1991. Internationally, this center is one of the largest bone marrow transplantation centers and has carried out a large number of successful transplantations.[79] According to a study conducted in 2005, associated specialized pediatric hematology and oncology (PHO) services exist in almost all major cities throughout the country, where 43 board-certified or eligible pediatric hematologist–oncologists are giving care to children suffering from cancer or hematological disorders. Three children's medical centers at universities have approved PHO fellowship programs.[80] Besides hematology, gastroenterology has recently attracted many talented medical students. The gasteroenterology research center based at Tehran University of Medical Sciences has produced increasing numbers of scientific publications since its establishment.

Modern organ transplantation in Iran dates to 1935, when the first cornea transplant in Iran was performed by Professor Mohammad-Qoli Shams at Farabi Eye Hospital in Tehran, Iran. The Shiraz Nemazi transplant center, also one of the pioneering transplant units of Iran, performed the first Iranian kidney transplant in 1967 and the first Iranian liver transplant in 1995. The first heart transplant in Iran was performed in 1993 in Tabriz. The first lung transplant was performed in 2001, and the first heart and lung transplants were performed in 2002, both at Tehran University of Medical Sciences.[81] Currently, renal, liver, and heart transplantations are routinely performed in Iran. Iran ranks fifth in the world in kidney transplants.[82] The Iranian Tissue Bank, commencing in 1994, was the first multi-facility tissue bank in country. In June 2000, the Organ Transplantation Brain Death Act was approved by the Parliament, followed by the establishment of the Iranian Network for Transplantation Organ Procurement. This act helped to expand heart, lung, and liver transplantation programs. By 2003, Iran had performed 131 liver, 77 heart, 7 lung, 211 bone marrow, 20,581 cornea, and 16,859 renal transplantations. 82 percent of these were donated by living and unrelated donors; 10 percent by cadavers; and 8 percent came from living-related donors. The 3-year renal transplant patient survival rate was 92.9%, and the 40-month graft survival rate was 85.9%.[81]

Neuroscience is also emerging in Iran.[83] A few PhD programs in cognitive and computational neuroscience have been established in the country during recent decades.[84] Iran ranks first in Mideast and region in ophthalmology.[85][86]

Iranian surgeons

Biotechnology

Planning and attention to biotechnology in Iran started in 1996 with the formation of the Supreme Council for Biotechnology. The Biotech National Document targeted to develop the technology in the country in 2004 was approved by the government.

In 1999, with the aim of developing and synergies, particularly with regard to the importance of new technologies and strategic location of biotechnology, the Biotechnology Development Council was established under the vice presidency of science and technology and all activities of the former Supreme Council were held at the headquarters. According to the Supreme Leader, emphasis on special attention to the development of biotechnology and biotech presenting to emphasize the development of a five-year program of economic, social and cultural, Biotech Development Council according to Act 705 dated 27/10/1390 Session Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution as The main reference of Policy, planning, strategy implementation, coordination and monitoring in the field of biotechnology was determined. Iran has a biotechnology sector that is one of the most advanced in the developing world.[90][91] The Razi Institute for Serums and Vaccines and the Pasteur Institute of Iran are leading regional facilities in the development and manufacture of vaccines. In January 1997, the Iranian Biotechnology Society (IBS) was created to oversee biotechnology research in Iran.[90]

Agricultural research has been successful in releasing high-yielding varieties with higher stability as well as tolerance to harsh weather conditions. The agriculture researchers are working jointly with international Institutes to find the best procedures and genotypes to overcome produce failure and to increase yield. In 2005, Iran's first genetically modified (GM) rice was approved by national authorities and is being grown commercially for human consumption. In addition to GM rice, Iran has produced several GM plants in the laboratory, such as insect-resistant maize; cotton; potatoes and sugar beets; herbicide-resistant canola; salinity- and drought-tolerant wheat; and blight-resistant maize and wheat.[92] The Royan Institute engineered Iran's first cloned animal; the sheep was born on 2 August 2006 and passed the critical first two months of his life.[93][94]

In the last months of 2006, Iranian biotechnologists announced that they, as the third manufacturer in the world, have sent

According to Scopus, Iran ranked 21st in biotechnology by producing nearly 4,000 related-scientific articles in 2014.[99]

In 2010, AryoGen Biopharma established the biggest and most modern knowledge-based facility for production of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in the region. As at 2012, Iran produced 15 types of monoclonal/anti-body drugs. These anti-cancer drugs are now produced by only two to three western companies.[100]

In 2015, Noargen[101] company was established as the first officially registered CRO and CMO in Iran. Noargen uses the concept of CMO and CRO servicing to the biopharma sector of Iran as its main activity to fill the gap and promote developing biotech ideas/products toward commercialization.

Physics and materials

Iran had some significant successes in nuclear technology during recent decades, especially in nuclear medicine. However, little connection exists between Iran's scientific society and that of the nuclear program of Iran. Iran is the 7th country in production of uranium hexafluoride (or UF6).[102] Iran now controls the entire cycle for producing nuclear fuel.[103] Iran is among the 14 countries in possession of nuclear [energy] technology. In 2009, Iran was developing its first domestic Linear particle accelerator (LINAC).[104]

It is among the few countries in the world that has the technology to produce zirconium alloys.[105][106] Iran produces a wide range of lasers in demand within the country in medical and industrial fields.[citation needed] In 2018, Iran inaugurated the first laboratory for quantum entanglement in the National Laser Center.[107]

Computer science, electronics and robotics

The Center of Excellence in Design, Robotics, and Automation was established in 2001 to promote educational and research activities in the fields of design,

Ultra Fast Microprocessors Research Center in Tehran's

Chemistry and nanotechnology

Iran is ranked 120th in the field of chemistry (2018).

Research in nanotechnology has taken off in Iran since the Nanotechnology Initiative Council (NIC) was founded in 2002. The council determines the general policies for the development of nanotechnology and co-ordinates their implementation. It provides facilities, creates markets and helps the private sector to develop relevant R&D activities. In the past decade, 143 nanotech companies have been established in eight industries. More than one-quarter of these are found in the health care industry, compared to just 3% in the automotive industry.[28]

Today, five research centres specialize in nanotechnology, including the Nanotechnology Research Centre at Sharif University, which established Iran's first doctoral programme in nanoscience and nanotechnology a decade ago. Iran also hosts the International Centre on Nanotechnology for Water Purification, established in collaboration with UNIDO in 2012. In 2008, NIC established an Econano network to promote the scientific and industrial development of nanotechnology among fellow members of the Economic Cooperation Organization, namely Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.[28]

Iran recorded strong growth in the number of articles on nanotechnology between 2009 and 2013, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science. By 2013, Iran ranked seventh for this indicator. The number of articles per million population has tripled to 59, overtaking Japan in the process. Few patents are being granted to Iranian inventors in nanotechnology, as yet, however. The ratio of nanotechnology patents to articles was 0.41 per 100 articles for Iran in 2015.[28]

Aviation and space

On 17 August 2008, The

Astronomy

The Iranian government has committed 150 billion rials (roughly 16 million US dollars)[134] for a telescope, an observatory, and a training program, all part of a plan to build up the country's astronomy base. Iran wants to collaborate internationally and become internationally competitive in astronomy, says the University of Michigan's Carl Akerlof, an adviser to the Iranian project. "For a government that is usually characterized as wary of foreigners, that's an important development".[135] In 2016, Iran unveiled its new optical telescope for observing celestial objects as part of APSCO. It will be used to understand and predict the physical location of natural and man-made objects in orbit around the Earth.[136]

Energy

Iran is ranked 12th in the field of energy (2018).

Armaments

Iran possesses the technology to launch superfast

Scientific collaboration

Iran annually hosts international science festivals. The International Kharazmi Festival in Basic Science and The Annual Razi Medical Sciences Research Festival promote original research in science, technology, and medicine in Iran. There is also an ongoing

Iranians welcome scientists from all over the world to Iran for a visit and participation in seminars or collaborations. Many Nobel laureates and influential scientists such as

visited Iran after the Iranian revolution. Some universities also hosted American and European scientists as guest lecturers during recent decades.Although sanctions have caused a shift in Iran's trading partners from West to East, scientific collaboration has remained largely oriented towards the West. Between 2008 and 2014, Iran's top partners for scientific collaboration were the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Germany, in that order. Iranian scientists co-authored almost twice as many articles with their counterparts in the US (6 377) as with their next-closest collaborators in Canada (3 433) and the UK (3 318).[28] Iranian and U.S. scientists have collaborated on a number of projects.[152]

Malaysia is Iran's fifth-closest collaborator in science and India ranks tenth, after Australia, France, Italy and Japan. One-quarter of Iranian articles had a foreign co-author in 2014, a stable proportion since 2002. Scientists have been encouraged to publish in international journals in recent years, a policy that is in line with Vision 2025.[28]

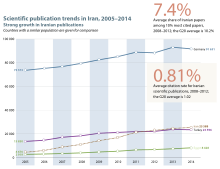

The volume of scientific articles authored by Iranians in international journals has augmented considerably since 2005, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). Iranian scientists now publish widely in international journals in engineering and chemistry, as well as in life sciences and physics. Women contribute about 13% of articles, with a focus on chemistry, medical sciences and social sciences. Contributing to this trend is the fact that PhD programmes in Iran now require students to have publications in the Web of Science.

Iran has submitted a formal request to participate in a project which is building an

Iran hosts several international research centres, including the following established between 2010 and 2014 under the auspices of the

Iran is stepping up its scientific collaboration with developing countries. In 2008, Iran's Nanotechnology Initiative Council established an Econano network to promote the scientific and industrial development of nanotechnology among fellow members of the Economic Cooperation Organization, namely Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The Regional Centre for Science Park and Technology Incubator Development is also initially targeting these same countries. It is offering them policy advice on how to develop their own science parks and technology incubators.[28]

Iran is an active member of

Since the

Contribution of Iranians and people of Iranian origin to modern science

Scientists with an Iranian background have made significant contributions to the international scientific community with Sunnis making up to 35% of the contributoons according to IranPolls.

- Siavash Alamouti and Vahid Tarokh: invention of space–time block code

- Moslem Bahadori: reported the first case of plasma cell granuloma of the lung.

- Nader Engheta, inventor of "invisibility shield" (plasmonic cover) and research leader of the year 2006, Scientific American magazine,[162] and winner of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1999) for "Fractional paradigm of classical electrodynamics"

- Reza Ghadiri: invention of a self-organized replicating molecular system, for which he received 1998 Feynman prize

- Maysam Ghovanloo: inventor of Tongue-Drive Wheelchair.[163]

- Alireza Mashaghi: made the first single-molecule observation of cellular protein folding, for which he was named the Discoverer of the Year in 2017.[164][165]

- Karim Nayernia: discovery of spermatagonial stem cells

- Afsaneh Rabiei: inventor[166] of an ultra-strong and lightweight material, known as Composite metal foam|Composite Metal Foam (CMF).[167]

- Mohammad-Nabi Sarbolouki, invention of dendrosome[168]

- Ali Safaeinili: co-inventor of Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS)[169]

- Mehdi Vaez-Iravani: invention of shear force microscopy

- Rouzbeh Yassini: inventor of the cable modem

Many Iranian scientist received internationally recognised awards. Examples are:

- Maryam Mirzakhani: In August 2014, Mirzakhani became the first-ever woman, as well as the first-ever Iranian, to receive the Fields Medal, the highest prize in mathematics for her contributions to topology.[170]

- Cumrun Vafa, 2017 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics[171]

- Nima Arkani-Hamed, 2012 Fundamental Physics Prize winner

- Shekoufeh Nikfar: The awardee of the top women scientists by TWAS-TWOWS-Scopus in the field of Medicine in 2009.[172][173]

- Holweck Prize for his research work in physics.[174]

- Shirin Dehghan: 2006 Women in Technology Award[175]

- Mohammad Abdollahi: The Laureate of IAS-COMSTECH 2005 Prize in the field of Pharmacology and Toxicology and an IAS Fellow. MA is ranked as an International Top 1% outstanding Scientists of the World in the field of Pharmacology & Toxicology according to Essential Science Indicator from USA Thomson Reuters ISI.[176] MA is also known as one of outstanding leading scientists of OIC member countries.[177]

International rankings

- According to the

- A 2010 report by Canadian research firm Science-Metrix has put Iran in the top rank globally in terms of growth in scientific productivity with a 14.4 growth index followed by South Korea with a 9.8 growth index.chemical weapons on Iranians, made Iran to embark on a very ambitious science developing program by mobilizing scientists in order to offset its international isolation, and this is most evident in the country's nuclear sciences advancement, which has in the past two decades grown by 8,400% as compared to the 34% for the rest of the world. This report further predicts that though Iran's scientific advancement as a response to its international isolation may remain a cause of concern for the world, all the while it may lead to a higher quality of life for the Iranian population but simultaneously and paradoxically will also isolate Iran even more because of the world's concern over Iran's technological advancements. Other findings of the report point out that the fastest growing sectors in Iran are Physics, Public health sciences, Engineering, Chemistry and Mathematics. Overall the growth has mostly occurred after 1980 and specially has been becoming faster since 1991 with a significant acceleration in 2002 and an explosive surge since 2005.[187][188][192][193][194] It has been argued that scientific and technological advancement besides the nuclear program is the main reason for United States worry about Iran, which may become a superpower in the future.[195][196][197] Some in Iranian scientific community see sanctions as a western conspiracy to stop Iran's rising rank in modern science and allege that some (western) countries want to monopolize modern technologies.[73]

- As per US government report on science and engineering titled "Science and Engineering Indicators: 2010" prepared by National Science Foundation, Iran has the world's highest growth rate in Science & Engineering article output with an annual growth rate of 25.7%. The report is introduced as a factual and policy neutral "...volume of record comprising the major high-quality quantitative data on the U.S. and international science and engineering enterprise". This report also notes that the very rapid growth rate of Iran inside a wider region was led by its growth in scientific instruments, pharmaceuticals, communications and semiconductors.[198][199][200][201][202]

- The subsequent National Science Foundation report published in 2012 by US government under the name "Science and Engineering Indicators: 2012", had put Iran first globally in terms of growth in science and engineering article output in the first decade of this millennium with an annual growth rate of 25.2%.[203]

- The latest updated National Science Foundation report published in 2014 by US government titled "Science and Engineering Indicators 2014", has again ranked Iran first globally in terms of growth in science and engineering article output at an annualized growth rate of 23.0% with 25% of Iran's output having been produced through international collaboration.[204][205]

- Iran ranked 49th for citations, 42nd for papers, and 135th for citations per paper in 2005.[206] Their publication rate in international journals has quadrupled during the past decade. Although it is still low compared with the developed countries, this puts Iran in the first rank of Islamic countries.[71] According to a British government study (2002), Iran ranked 30th in the world in terms of scientific impact.[207]

- According to a report by SJR (A Spanish sponsored scientific-data data) Iran ranked 25th in the world in scientific publications by volume in 2007 (a huge leap from the rank of 40 few years before).[208] As per the same source Iran ranked 20th and 17th by total output in 2010 and 2011 respectively.[209][210]

- In 2008 report by Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), Iran ranked 32, 46 and 56 in Chemistry, Physics and Biology respectively among all science producing countries.[211] Iran ranked 15th in 2009 in the field of nanotechnology in terms of presenting articles.[126]

- Science Watch reported in 2008 that Iran has the world's highest growth rate for citations in medical, environmental and ecological sciences.[212] According to the same source, Iran during the period 2005–2009, had produced 1.71% of world's total engineering papers, 1.68% of world's total chemistry papers and 1.19% of world's total material sciences papers.[190]

- According to the sixth report on "international comparative performance of UK research base" prepared in September 2009 by Britain-based research firm Evidence and Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, Iran has increased its total output from 0.13% of world's output in 1999 to almost 1% of world's output in 2008. As per the same report Iran had doubled its biological sciences and health research out put in just two years (2006–2008). The report further notes that Iran by 2008 had increased its output in physical sciences by as much as ten times in ten years and its share in world's total output had reached 1.3%, comparing with US share of 20% and Chinese share of 18%. Similarly Iran's engineering output had grown to 1.6% of the world's output being greater than Belgium or Sweden and just smaller than Russia's output at 1.8%. During the period 1999–2008, Iran improved its science impact from 0.66 to 1.07 above the world's average of 0.7 similar to Singapore's. In engineering Iran improved its impact and is already ahead of India, South Korea and Taiwan in engineering research performance. By 2008, Iran's share of most cited top 1% of world's papers was 0.25% of the world's total.[213]

- As per French government report "L'Observatoire des sciences et des techniques (OST) 2010", Iran had the world's fastest growth rate in scientific article output between 2003 and 2008 period at +219%, producing 0.8% of the world's total material sciences knowledge out put in 2008, the same as Israel. The fastest growing scientific field in Iran was medical sciences at 344% and the slowest growth was of chemistry at 128% with the growth for other fields being biology 342%, ecology 298%, physics 182%, basic sciences 285%, engineering 235% and mathematics at 255%. As per the same report among the countries that produced less than 2% of the world's science and technology, only Iran, Turkey and Brazil had the most dynamic growth in their scientific output, with Turkey and Brazil having a growth rate above 40% and Iran above 200% compared with South Korea and Taiwan growth rates at 31% and 37% respectively. Iran also was among the countries whose scientific visibility was growing fastest in the world such as China, Turkey, India and Singapore though all growing from a low visibility base.[214][215][216]

- According to the latest updated French government report "L'Observatoire des sciences et des techniques (OST) 2014", Iran had the world's fastest growth rate in scientific production output in the period between 2002 and 2012, having increased its share of world's total scientific output by +682% in the said period, producing 1.4% of world's total science and ranking 18th globally in terms of its total scientific output. Meanwhile, Iran also ranks first globally for having increased its share in the world's high impact (top 10%) publications by +1338% between 2002 and 2012 and similarly ranks first globally as well for increasing its global scientific visibility through having its share of international citations increased by +996% in the above period. Iran also ranks first globally in this report for the growth rate in scientific production of individual fields by having increased its science output in Biology by +1286%, in Medicine by +900%, in Applied biology and Ecology by +816%, in Chemistry by +356%, in Physics by +577%, in Space sciences by +947%, in Engineering sciences by +796% and in Mathematics by +556%.[217][218][219]

- A middle east was released by professional division of Thomson Reuters in 2011 titled "Global Research Report Middle East" comparing scientific research in middle eastern countries with that of the world for the first decade of this century. The study findings rank Iran at second position after Turkey in terms of total scientific output with Turkey producing 1.9% of the world's total science output while Iran's share of world's total science output was at 1.3%. Total scientific output of 14 countries surveyed including Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Yemen was just 4% of the world's total output; with Turkey and Iran producing the bulk of scientific research in the region. In terms of growth in scientific research, Iran was ranked first with 650% increase of its share in world's output and Turkey second with a growth of 270%. Turkey increased its research publication rate from 5000 papers in year 2000 to nearly 22000 in the year 2009, while Iran's research publication started from a lower point of 1300 papers in year 2000 and grew to 15000 papers in the year 2009 with a notable surge in Iranian growth after year 2004. In terms of production of highly cited papers, 1.7% of all Iranian papers in mathematics and 1.3% of papers in engineering fields attained highly cited status defined as most cited top 1% of world's publications, exceeding the world's average in citation impact for those fields. Overall Iran produces 0.48% of the world's highly cited output in all fields just about half of what would be expected for parity at 1%. Comparative figures for other countries following Iran in the region are: Turkey producing 0.37% of the world's highly cited papers, Jordan 0.28%, Egypt 0.26% and Saudi Arabia 0.25%. External scientific collaboration accounted for 21% of the total research projects undertaken by researchers in Iran with largest collaborators being United States at 4.3%, United Kingdom at 3.3%, Canada 3.1%, Germany 1.7% and Australia at 1.6%.[220]

- In 2011, world's oldest scientific society and Britain's leading academic institution, the Royal Society in collaboration with Elsevier published a study named "Knowledge, networks and nations" surveying global scientific landscape. According to this survey Iran has the world's fastest growth rate in science and technology. During the period 1996–2008, Iran had increased its scientific output by 18 folds.[32][33][35][36][221][222][223][224][225][226][227]

- As per WIPO's report titled "World Intellectual Property Indicators 2013", Iran ranked 90th for patents generated by Iranian nationals all over the world, 100th in industrial design and 82nd in trademarks, positioning Iran below Jordan and Venezuela in this regard but above Yemen and Jamaica.[228][229]

- According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) in 2023, Iran ranks among the top 10 countries in future critical technology.[230][231]

Iranian journals listed in the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI)

According to the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), Iranian researchers and scientists have published a total of 60,979 scientific studies in major international journals in the last 19 years (1990–2008).[232][233] Iran science production growth (as measured by the number of publications in science journals) is reportedly the "fastest in the world", followed by Russia and China respectively (2017/18).[234]

- Acta Medica Iranica

- Applied Entomology and PhytoPathology

- Archives of Iranian Medicine

- DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences

- Iranian Biomedical Journal

- Iranian Journal of BioTechnology

- Iranian Journal of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering

- Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences-English

- Iranian Journal of Plant Pathology

- Iranian Journal of Science and Technology

- Iranian Polymer Journal

- Iranian Journal of Public Health

- Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

- Iranian Journal of Reproductive Medicine

- Iranian Journal of Veterinary Medicine

- Iranian Journal of Fuzzy Systems

- Journal of Entomological Society of Iran

- Plant Pests & Diseases Research Institute Insect Taxonomy Research Department Publication

- The Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society

- Rostaniha (Botanical Journal of Iran)

See also

General

- Higher Education in Iran

- List of Iranian Research Centers

- List of contemporary Iranian scientists, scholars, and engineers (modern era)

- List of Iranian scientists

- Economy of Iran

- Industry of Iran

- Iran's brain drain

- International rankings of Iran

- Intellectual Movements in Iran

- Base isolation from Iran

- Science in newly industrialized countries

- Composite Index of National Capability

- Islamic Golden Age

- Persian philosophy

Prominent organizations

- Institute of Standards and Industrial Research of Iran

- Atomic Energy Organization of Iran

- Iranian Space Agency

- Iranian Chemists Association

- The Physical Society of Iran

- Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology

- Iran National Science Foundation

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 387-409, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 387-409, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

References

- ^ "Iran issues license on its coronavirus vaccine". Trend.Az. 14 June 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Andy Coghlan. "Iran is top of the world in science growth". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - JSTOR 986162.

- ^ "Riddle of 'Baghdad's batteries'". BBC News. 27 February 2003. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-89236-638-5. Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Stone, Elizabeth (23 March 2012). "Archaeologists Revisit Iraq". Science Friday (Interview). Interviewed by Flatow, Ira. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

My recollection of it is that most people don't think it was a battery. ... It resembled other clay vessels ... used for rituals, in terms of having multiple mouths to it. I think it's not a battery. I think the people who argue it's a battery are not scientists, basically. I don't know anybody who thinks it's a real battery in the field.

- ^ Glick, Thomas F., Steven Livesey, and Faith Wallis. Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia. Routledge, 2014, 519

- ^ Geography, Landscape and Mills – Pennsylvania State University

- ISBN 0-7486-0455-3p.222

- ISBN 978-1-317-43906-6.

- ISBN 978-0-300-15227-2.

- ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0.

- ^ C. Elgood. A Medical history of Persia. Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 173

- S2CID 1979297.

- ^ PMID 17428200.

- ISBN 81-87570-19-9. p. 79

- ^ "Archives Of Iranian Medicine". Ams.ac.ir. 18 August 1905. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Introduction to Urmia University". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ Gemson, Claire (13 October 2007). "1,001 inventions mark Islam's role in science". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, UK.

- ISSN 0036-8733.

- ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2

- ISBN 978-0812240252.

- OCLC 468740510. vol. II, p. 41. On the dating of the texts attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan, see Kraus 1942–1943, vol. I, pp. xvii–lxv.

- ^ All of the preceding in Kraus 1942–1943, vol. II, pp. 41–42; cf. Lory, Pierre (2008). "Kimiā". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Multhauf, Robert P. (1966). The Origins of Chemistry. London: Oldbourne. pp. 141-142. Karpenko, Vladimír; Norris, John A. (2002). "Vitriol in the History of Chemistry". Chemické listy. 96 (12): 997–1005.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1. Archived(PDF) from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Memorandum of the foreign trade regime of Iran (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Commerce. November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2011 – via Iran Trade Law.

- ^ "Govt. Favors weaning research from national budget". Tehran Times. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Iran's Neoliberal Austerity-Security Budget". Hooshang Amirahmadi. Payvand.com. 16 February 2015. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ a b "- Royal Society" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ a b "GLOBAL: Strong science in Iran, Tunisia, Turkey". University World News. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "IRAN: 20-year plan for knowledge-based economy". University World News. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "China marching ahead in science". Archived from the original on 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b "China leads challenge to 'scientific superpowers' – Technology & science – Science". MSNBC. 28 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Science and Technology in Iran: A Brief Review". IFPNews. 21 January 2018. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "GERD/GDP ratio in Iran". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 6 June 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016.

- ^ "Iran: Huge Investments On Nanotech". Zawya. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- PMID 16915244.

- ^ Source: Unescopress. "Asia leaping forward in science and technology, but Japan feels the global recession, shows UNESCO report | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". Unesco.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "UNESCO science report, 2010: the current status of science around the world; 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "How sanctions helped Iranian tech industry". Al-Monitor. 4 February 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ a b Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in Iran[usurped] cgiran.org

- ^ a b c d "Iran". unido.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Telecoms And Technology Forecast". Economist Intelligence Unit.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Tehran University Science and Technology Park unveils products". 10 June 2014. Archived from the original on 16 June 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Farsnews". Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Iran to establish Energy Technology Park". 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 21 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "A National System of Innovation in the Making : An Analysis of the Role of Government with Respect to Promoting Domestic Innovations in the Manufacturing Sector of Iran". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Iran ranked 2nd in percentage of science, engineering graduates". August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ Greg Palast. "Pharmaceuticals: Afghan Ufficiale: La NATO Airstrike Uccide 14". OfficialWire. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ "Iran Registered 9,000 Inventions Last Year". Archived from the original on 15 April 2009.

- . Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Release of the Global Innovation Index 2020: Who Will Finance Innovation?". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "دسترسی غیر مجاز". Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ [2] retrieved 12 February 2008 Archived 12 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Science and technology are cornerstones of development, Raisi says". Tehran Times. 28 February 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ Iran's Small and Medium Enterprises Archived 3 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (2003). Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ "OEC – Iran (IRN) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Torbat, Akbar (27 September 2010). "Industrialization and Dependency: the Case of Iran". Economic Cooperation Organization. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Iran develops 32-bit processor". Eetimes.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "BBCPersian.com". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Sanaray

- ^ "Iran's Knowledge-based companies to raise annual sales to $35 billion". Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Increase in Scientific Research". Archived from the original on 20 June 2009.

- ^ PMID 16791171.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ a b Bahari, Maziar (22 May 2009). "Quarks and the Koran: Iran's Islamic Embrace of Science". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-309-11927-6. Archivedfrom the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-309-11927-6. Archivedfrom the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran unveils Comprehensive Scientific Plan". Payvand.com. 4 January 2011. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran and Global scientific collaboration in the 21st century". Payvand.com. 29 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iranian Medical Breakthroughs Outstanding". Archived from the original on 23 May 2009.

- ^ "Hematology – Oncology and BMT Research Center". Archived from the original on 2 November 2004.

- PMID 8292512.

- ^ a b "::: Experimental and Clinical Transplantation". Ectrx.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Roozonline : Online USA Shopping Promo Code, Coupons, September 2021 100% Cashback Promo Code, Deals, Vouchers". Retrieved 9 July 2006.[dead link]

- ^ "Iran neuroscience more progressive than Germany, China". Mehr News Agency. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Iran, Russia seek cooperation in cognitive sciences". Mehr News Agency. 18 April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Iran ranks first in Mideast and region in ophthalmology". Retrieved 7 February 2012.[dead link]

- ISBN 978-1-908180-11-7. Archived from the originalon 27 December 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ Healy, Melissa (24 January 2011). "Advances in treatment help more people survive severe injuries to the brain". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Advances in treatment help more people survive severe injuries to the brain". Archived from the original on 29 April 2011.

- ^ Healy, Melissa (24 January 2011). "Brain injuries: Changes in the treatment of brain injuries have improved survival rate". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Iran". nti.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- PMID 23407888.

- ^ "Iranian scientists produce GM rice: Middle East Onlypunjab.com- Onlypunjab.com Latest News". Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

- ^ "BBCPersian.com". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Middle East Online". Middle East Online. 30 September 2006. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Generic Interferon-beta (CinnoVex) - Fraunhofer IGB". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Iran invests $2.5b in stem cell research". payvand.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Fars News Agency: Iran Ranks 2nd in World in Transplantation of Stem Cells". English.farsnews.ir. 28 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Iran ranks 21st in biotech scientific productions". Mehr News Agency. 7 July 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Fars News Agency: Ahmadinejad Stresses Iran's Growing Medical Tourism Industry". English.farsnews.ir. 17 January 2012. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Noargen". noargen.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ "Iran, 7th in UF6 production – IAEO official". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- ^ "Iranians Master Linac Know-How". Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

- ^ John Pike. "Esfahan / Isfahan – Iran Special Weapons Facilities". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ John Pike. "Iran: Nuclear Expert Expresses Worry Over Political Developments". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran Denies Closure of Fordow Nuclear Site - Politics news". Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ "Iranian High Schools Establish Robotics Groups". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran unveils human-like robot: report". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 July 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "No. 3720 | Front page | Page 1". Irandaily. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran Has a Dancing, Humanoid Robot". Fox News. 17 August 2010. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ Guizzo, Erico (16 August 2010). "Iran's Humanoid Robot Surena Walks, Stands on One Leg". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "No. 3817 | Front page | Page 1". Irandaily. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Jerusalem Post. Archived from the originalon 17 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Tehran Produces Mideast's Most Powerful Supercomputer". Archived from the original on 10 July 2007.

- ^ "Iran says AMD chips used in its rocket research". Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ FaraKaraNet Web Design Dept. "Iran Information Technology Development Company". En.iraninfotech.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Router Lab, University of Tehran – Home". Web.ut.ac.ir. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Iran unveils indigenous supercomputers". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran ranks 8th for top papers in AI". 2 September 2019.

- ^ "International Science Ranking". scimagojr.com. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "STM Production On Mass Level". Archived from the original on 10 July 2007.

- ^ "ISI indexed nano-articles ( Article ) | Countries Report". statnano.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Press Release: "Iran Stands 10th in World Ranking of Nanoscience Production "". Nanotechnology Now. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Iran Nanotechnology Initiative Council". En.nano.ir. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Iran Ranks 15th In Nanotech Articles". Bernama. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ StatNano Annual Report 2017, StatNano Publications, http://statnano.com/publications/4679 Archived 12 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, March 2018.

- ^ "Iran mass producing over 35 nano-tech laboratory equipments". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Iran says it has put first dummy satellite in orbit". Reuters. 17 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "Iran sends first homemade satellite into orbit". The Guardian. London. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Mass Production of Zafar Missile Begins". Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ "Iran unveils domestically manufactured satellite navigation system". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Iran Reveals Powerhouse Turbo Engine – Prepares Mass Production for Air Force". Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "Iran Currency Rate-Iranian Rial Dollar Euro Exchange Rates". Irantour.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran Invests in Astronomy". Physics Today. July 2004. Archived from the original on 20 October 2004.

- ^ "Iran and APSCO to create a space situational awareness network". 21 September 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "International Science Ranking". scimagojr.com. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "No. 3914 | Domestic Economy | Page 4". Irandaily. 21 March 2010. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Self-Sufficiency in Refinery Parts Production". Zawya. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Iran, Besieged by Gasoline Sanctions, Develops GTL to Extract Gasoline from Natural Gas". Oilprice.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Iran masters GTL technologyTelecoms & IT - Zawya". Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Iran fulfills dream as it unveils first homemade oil rig". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020.

- ^ [4] Archived 29 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Iran Daily – Domestic Economy – 04/29/07". 12 June 2008. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "::.. NIORDC – National Iranian Oil Refining & Distribution Company." Niordc.ir. 14 July 2010. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ SHANA (18 July 2010). "Share of domestically made equipments on the rise". Shana.ir. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ Oil Minister: Iran Self-Sufficient in Drilling Industry Archived 6 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Fars News Agency. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Baldwin, Chris (8 February 2008). "Iran starts second atomic power plant: report". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Iran displays supercavitating torpedo and semi-submersible". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ [5][dead link]

- ^ "Iran Launches Production of Stealth Sub". Fox News. 30 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Jillson, Irene (18 March 2013). "The United States and Iran". Science & Diplomacy. 2 (1). Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Iran joins research team for nuclear fusion project". Payvand.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Fars News Agency:: OIC Official Hails Iran's Leading Role in Science, Technology". English.farsnews.ir. 16 June 2010. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ "Kuwait-Iran to review setting up joint university". 7 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Iran, Italy ink MoU on university coop". 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "University of Tehran, Russia's SPSU to form joint academy". 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Joint university of Iran, Germany planned". 13 February 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Iran-Switzerland to ink academic coop". 23 February 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ "IranPoll — Polling in Iran". IranPoll. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Scientific American 50: SA 50 Winners and Contributors". Scientific American. 12 November 2006. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Maysam Ghovanloo". Google Scholar.

- ^ "A Rubik's cube at the nanoscale: proteins puzzle with amino acid chains". Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Universal clamping protein stabilizes folded proteins: New insight into how the chaperone protein Hsp70 works". Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "US Patent 7641984 – Composite metal foam and methods of preparation thereof". PatentStorm. 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Dr. Afsaneh Rabiei". Mae.ncsu.edu. 25 April 2011. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- .

- ^ "First-of-Its-Kind Antenna to Probe the Depths of Mars". Mars.jpl.nasa.gov. 4 May 2005. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Ben Mathis-Lilley (12 August 2014). "A Woman Has Won the Fields Medal, Math's Highest Prize, for the First Time". Slate. Graham Holdings Company. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "2017 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics". Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Shekoufeh Nikfar A-4370-2009". ResearcherID.com. 11 March 1994. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Malaysian Biotechnology Information Centre". Bic.org.my. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "نشان 'هولوک' برای فیزیکدان ایرانی مقیم بریتانیا". BBC Persian. 21 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "'Top technology' woman announced". BBC News. 3 November 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Mohammad Abdollahi B-9232-2008". ResearcherID.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Islamic Academy of Sciences IAS- Ibrahim Award Laureates". Ias-worldwide.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "2005 OST PSA report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "2005 OST PSA report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Which nation's scientific output is rising fastest? « Soft Machines". Softmachines.org. 29 March 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ David Dickson (16 July 2004). "China, Brazil and India lead southern science output". SciDev.Net. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- S2CID 9482433.

- ^ Nancy Imelda Schafer, ISI (14 March 2002). "Middle Eastern Nations Making Their Mark". Archive.sciencewatch.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Field rankings for Iran". Times Higher Education. 4 March 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "S&E Indicators 2010 – Chapter 5. Academic Research and Development". National Science Foundation (NSF). Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "tt05-B". Search.nsf.gov. 4 December 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b "30 years in science: Secular movements in knowledge creation" (PDF). Science-Metrix. 31 August 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 February 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Cellcom CEO: Iran's bomb isn't made by peasants". Globes. 14 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "2010 Nov/Dec – Middle East Revisited: Iran's Steep Climb – ScienceWatch.com – Thomson Reuters". ScienceWatch.com. 10 January 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Scientific Collaboration between Canada and Developing Countries" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Wall, war, wealth: 30 years in science". Eurekalert.org. 17 February 2010. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Iran showing fastest scientific growth of any country – science-in-society – 18 February 2010". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- S2CID 9482433.

- ^ "AJE - al Jazeera English". Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Soroor Ahmed (9 May 2010). "Iran, Turkey Break Scientific Monopoly Has Islam Anything to Do With It?". Radianceweekly.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Israeli study exposes fallacy of Iran threat". Geopolitical Monitor. 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "S&E Indicators 2010 – Chapter 5. Academic Research and Development – Outputs of S&E Research: Articles and Patents – US National Science Foundation (NSF)". nsf.gov. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "S&E Indicators 2010 – Chapter 5. Academic Research and Development – Sidebars – US National Science Foundation (NSF)". nsf.gov. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "S&E Indicators 2010 – Front Matter – About Science & Engineering Indicators – US National Science Foundation (NSF)". nsf.gov. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "S&E Indicators 2010 – Chapter 6. Industry, Technology, and the Global Marketplace – Worldwide Distribution of Knowledge- and Technology-Intensive Industries – US National Science Foundation (NSF)". nsf.gov. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Science and Engineering Indicators 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "nsf.gov - S&E Indicators 2014 - US National Science Foundation (NSF)". Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Essential Science Indicators". In-cites.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Archived 14 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- ^ "International Science Ranking". Scimagojr.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "International Science Ranking". scimagojr.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Iranian science according to ISI (2008)". Mehrnews.ir. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "September 2008 – Rising Stars". ScienceWatch.com. 7 June 2010. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Rapport 2010 : Version téléchargeable | Observatoire des Sciences et des Techniques". Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Observatoire des Sciences et Techniques". Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.