Scotland in the early Middle Ages

| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the early

Scotland has an extensive coastline, vast areas of difficult terrain and poor agricultural land. In this period, more land became marginal due to climate change, resulting in relatively light human settlement, particularly in the interior and

Some highly distinctive monumental and ornamental art, culminating in the development of the Insular art style, are common across Britain and Ireland. The most impressive structures included nucleated hill forts and, after the introduction of Christianity, churches and monasteries. The period also saw the beginnings of Scottish literature in British, Old English, Gaelic and Latin languages.

Sources

As the first half of the period is largely

History

By the time of Bede and Adomnán, in the late seventh century and early eighth century, four major circles of influence had emerged in northern Britain. In the east were the Picts, whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the river Forth to Shetland. In the west were the Gaelic (

Picts

The confederation of Pictish tribes that developed north of the

In the 7th century, the Picts acquired

Dál Riata

The Gaelic overkingdom of Dál Riata was on the western coast of modern Scotland, with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. It probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd, now near Kilmartin in

In 563, a mission from Ireland under

Alt Clut

The kingdom of Alt Clut took its name from the Northern Brittonic for 'rock of the Clyde', today's Dumbarton Rock, which derives from the Gaelic for 'fort of the Britons'.[14]

The kingdom may have had its origins with the

After 600, information on the Britons of Alt Clut becomes more common in the sources. In 642, led by Eugein son of Beli, they defeated the men of Dál Riata and killed Domnall Brecc, grandson of Áedán, at Strathcarron.[16] The kingdom suffered a number of attacks from the Picts under Óengus, and later the Picts' Northumbrian allies between 744 and 756. They lost the region of Kyle in the southwest of modern Scotland to Northumbria, and the last attack may have forced the king Dumnagual III to submit to his neighbours.[17] After this, little is heard of Alt Clut or its kings until Alt Clut was besieged and captured by Vikings in 870, at which point the Clyde Britons seem to have reconstituted a kingdom based on a centre at Patrick and the Clyde Britons' existing Christian centre at Govan, home of The Govan Stones.[14]

Bernicia

The Brythonic successor states of what is now the modern Anglo-Scottish border region are referred to by Welsh scholars as part of Yr

Ida's grandson,

Vikings and the Kingdom of Alba

The balance between rival kingdoms was transformed in 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen.

The immediate descendants of Cináed were styled either as King of the Picts or King of

Geography

Physical geography

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland

Settlement

Roman influence beyond Hadrian's Wall does not appear to have had a major impact on settlement patterns, with

Place-name evidence, particularly the use of the prefix "pit", meaning land or a field, suggests that the heaviest areas of Pictish settlement were in modern Fife, Perthshire, Angus, Aberdeen and around the Moray Firth, although later Gaelic migration may have erased some Pictish names from the record.[5] Early Gaelic settlement appears to have been in the regions of the western mainland of Scotland between Cowal and Ardnamurchan, and the adjacent islands, later extending up the West coast in the 8th century.[44] There is a place name and archaeological evidence of Anglian settlement in south-east Scotland reaching into West Lothian, and to a lesser extent into south-western Scotland.[45] Later Norse settlement was probably most extensive in Orkney and Shetland, with lighter settlement in the western islands, particularly the Hebrides and on the mainland in Caithness, stretching along fertile river valleys through Sutherland and into Ross. There was also extensive Viking settlement in Bernicia, the Northern part of Northumbria, which stretched into the modern Borders and Lowlands.[46]

Language

This period saw dramatic changes in the geography of language. Modern linguists divide the Celtic languages into two major groups, the

Economy

Lacking the urban centres created under the Romans in the rest of Britain, the economy of Scotland in the early Middle Ages was overwhelmingly agricultural. Without significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by

Demography

There are almost no written sources from which to reconstruct the demography of early Medieval Scotland. Estimates have been made of a population of 10,000 inhabitants in Dál Riata and 80–100,000 for Pictland.[53] The 5th and 6th centuries likely saw higher mortality rates due to the appearance of bubonic plague, which may have reduced net population.[38] The known conditions have been taken to suggest it was a high fertility, high mortality society, similar to many developing countries in the modern world, with a relatively young demographic profile, and perhaps early childbearing, and large numbers of children for women. This would have meant that there was a relatively small proportion of available workers to the number of mouths to feed. This would have made it difficult to produce a surplus that would allow demographic growth and more complex societies to develop.[50]

Society

The primary unit of social organisation in Germanic and Celtic Europe was the kin group.

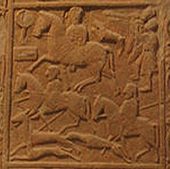

Scattered evidence, including the records in Irish annals and the images of warriors like those depicted on the Pictish stone slabs at

Indications are that society in North Britain contained relatively large numbers of slaves, often taken in war and raids, or bought, as St. Patrick indicated the Picts were doing from the Britons in Southern Scotland.[53] Slavery probably reached relatively far down in society, with most rural households containing some slaves. Because they were taken relatively young and were usually racially indistinguishable from their masters, many slaves would have been more integrated into their societies of capture than their societies of origin, in terms of both culture and language. Living and working beside their owners they in practice may have become members of a household without the inconvenience of the partible inheritance rights that divided estates. Where there is better evidence from England and elsewhere, it was common for such slaves who survived to middle age to gain their freedom, with such freedmen often remaining clients of the families of their former masters.[50][59]

Kingship

In the early Medieval period, British kingship was not inherited in a direct line from previous kings, as would be the case in the late Middle Ages. There were instead a number of candidates for kingship, who usually needed to be a member of a particular dynasty and to claim descent from a particular ancestor.[61] Kingship could be multi-layered and very fluid. The Pictish kings of Fortriu were probably acting as overlords of other Pictish kings for much of this period and occasionally were able to assert an overlordship over non-Pictish kings, but occasionally themselves had to acknowledge the overlordship of external rulers, both Anglian and British. Such relationships may have placed obligations to pay tribute or to supply armed forces. After a victory, sub-kings may have received rewards in return for this service. Interaction with and intermarriage into the ruling families of subject kingdoms may have opened the way to the absorption of such sub-kingdoms and, although there might be later overturnings of these mergers, likely, a complex process by which kingship was gradually monopolised by a handful of the most powerful dynasties was taking place.[62]

The primary role of the king was to act as a war leader, reflected in the very small number of minority or female reigning monarchs in the period. Kings organised the defence of their people's lands, property and persons and negotiated with other kings to secure these things. If they failed to do so, the settlements might be raided, destroyed or annexed, and the populations killed or taken into slavery. Kings also engaged in the low-level warfare of raiding and the more ambitious full-scale warfare that led to conflicts of large armies and alliances, and which could be undertaken over relatively large distances, such as the expedition to Orkney by Dál Riata in 581 or the Northumbrian attack on Ireland in 684.[62]

Kingship had its ritual aspects. The kings of Dál Riata were inaugurated by putting their foot in a footprint carved in stone, signifying that they would follow in the footsteps of their predecessors.

Warfare

At the most basic level, a king's power rested on the existence of his bodyguard or war-band. In the British language, this was called the teulu, as in teulu Dewr (the "War-band of Deira"). In Latin the word is either comitatus or tutores, or even familia; tutores is the most common word in this period, and derives from the Latin verb tueor, meaning "defend, preserve from danger".[65] The war-band functioned as an extension of the ruler's legal person, and was the core of the larger armies that were mobilised from time to time for campaigns of significant size. In peacetime, the war-band's activity was centred on the "Great Hall". Here, in both Germanic and Celtic cultures, the feasting, drinking and other forms of male bonding that kept up the war-band's integrity would take place. In the epic poem Beowulf, the war-band was said to sleep in the Great Hall after the lord had retired to his adjacent bed chamber.[66] It is not likely that any war-band in the period exceeded 120–150 men, as no hall structure having a capacity larger than this has been found by archaeologists in northern Britain.[67] Pictish stones, like that at Aberlemno in Angus, show mounted and foot warriors with swords, spears, bows, helmets and shields.[62] The large number of hill forts in Scotland may have made open battle less important than in Anglo-Saxon England and the relatively high proportion of kings who are recorded as dying in fires or drowning suggest that sieges were a more important part of warfare in Northern Britain.[62]

Sea power may also have been important. Irish annals record an attack by the Picts on Orkney in 682, which must have necessitated a large naval force:[68] they also lost 150 ships in a disaster in 729.[69] Ships were also vital in the amphibious warfare in the Highlands and Islands and from the seventh century the Senchus fer n-Alban indicates that Dál Riata had a ship-muster system that obliged groups of households to produce a total of 177 ships and 2,478 men. The same source mentions the first recorded naval battle around the British Isles in 719 and eight naval expeditions between 568 and 733.[70] The only vessels to survive from this period are dugout canoes, but images from the period suggest that there may have been skin boats (similar to the Irish currach) and larger oared vessels.[71] The Viking raids and invasions of the British Isles were based on superior sea power. The key to their success was a graceful, long, narrow, light, wooden boat with a shallow draft hull designed for speed. This shallow draft allowed navigation in waters only 3 feet (1 m) deep and permitted beach landings, while its light weight enabled it to be carried over portages. Longships were also double-ended, the symmetrical bow and stern allowing the ship to reverse direction quickly without having to turn around.[72][73]

Religion

Pre-Christian religion

Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. The lack of native written sources among the Picts means that it can only be judged from parallels elsewhere, occasional surviving archaeological evidence and hostile accounts of later Christian writers. It is generally presumed to have resembled

Early Christianisation

The roots of Christianity in Scotland can probably be found among the soldiers, notably Saint

The growth of Christianity in Scotland has been traditionally seen as dependent on Irish-Scots "Celtic" missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England.

Among the key indicators of Christianisation are long-

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity differed in some respects from that based on Rome, most importantly on the issues of how Easter was calculated and the method of tonsure, but there were also differences in the rites of ordination, baptism and in the liturgy. Celtic Christianity was heavily based on monasticism. Monasteries differed significantly from those on the continent, and were often an isolated collection of wooden huts surrounded by a wall. Because much of the Celtic world lacked the urban centres of the Roman world, bishoprics were often attached to abbeys. In the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, Irish monks established monastic institutions in parts of modern-day Scotland. Monks from Iona, under St. Aidan, then founded the See of Lindisfarne in Anglian Northumbria.[90] The part of southern Scotland dominated by the Anglians in this period had a Bishopric established at Abercorn in West Lothian, and it is presumed that it would have adopted the leadership of Rome after the Synod of Whitby in 663, until the Battle of Dunnichen in 685, when the Bishop and his followers were ejected.[68] By this time the Roman system of calculating Easter and other reforms had already been adopted in much of Ireland.[90] The Picts accepted the reforms of Rome under Nechtan mac Der-Ilei around 710.[68] The followers of Celtic traditions retreated to Iona and then to Innishbofin and the Western isles remained an outpost of Celtic practice for some time.[90] Celtic Christianity continued to influence religion in England and across Europe into the late Middle Ages as part of the Hiberno-Scottish mission, spreading Christianity, monasteries, art and theological ideas across the continent.[91]

Viking paganism

The Viking occupation of the islands and coastal regions of modern Scotland brought a return to pagan worship in those areas. Norse paganism had some of the same gods as had been worshipped by the Anglo-Saxons before their conversion and is thought to have been focused around a series of cults, involving gods, ancestors and spirits, with calendric and life cycle rituals often involving forms of sacrifice.[92] The paganism of the ruling Norse elite can be seen in goods found in 10th century graves in Shetland, Orkney and Caithness.[93] There is no contemporary account of the conversion of the Vikings in Scotland to Christianity.[94] Historians have traditionally pointed to a process of conversion to Christianity among Viking colonies in Britain dated to the late 10th century, for which later accounts indicate that Viking earls accepted Christianity. However, there is evidence that conversion had begun before this point. There are a large number of isles called Pabbay or Papa in the Western and Northern Isles, which may indicate a "hermit's" or "priest's isle" from this period. Changes in patterns of grave goods and Viking place names using -kirk also suggests that Christianity had begun to spread before the official conversion.[95] Later documentary evidence suggests that a Bishop was operating in Orkney in the mid-9th century and more recently uncovered archaeological evidence, including explicitly Christian forms such as stone crosses,[94] suggest that Christian practice may have survived the Viking take over in parts of Orkney and Shetland and that the process of conversion may have begun before Christianity was officially accepted by Viking leaders.[96] The continuity of Scottish Christianity may also explain the relatively rapid way in which Norse settlers were later assimilated into the religion.[97]

Art

From the 5th to the mid-9th centuries the art of the Picts is primarily known through stone sculpture, and a smaller number of pieces of metalwork, often of very high quality. After the conversion of the Picts and the cultural assimilation of Pictish culture into that of the Scots and Angles, elements of Pictish art became incorporated into the style known as Insular art, which was common over Britain and Ireland and became highly influential in continental Europe and contributed to the development of Romanesque styles.[98]

Pictish stones

About 250 Pictish stones survive and have been assigned by scholars to three classes.

Pictish metalwork

Metalwork has been found throughout Pictland; the Picts appear to have had a considerable amount of silver available, probably from raiding further south, or the payment of subsidies to keep them from doing so. The very large hoard of late Roman hacksilver found at Traprain Law may have originated in either way. The largest hoard of early Pictish metalwork was found in 1819 at Norrie's Law in Fife, but unfortunately, much was dispersed and melted down.[101] Over ten heavy silver chains, some over 0.5 metres (2 ft) long, have been found from this period; the double-linked Whitecleuch Chain is one of only two that have a penannular ring, with symbol decoration including enamel, which shows how these were probably used as "choker" necklaces.[101] The St Ninian's Isle Treasure contains perhaps the best collection of Pictish forms.[102]

Irish-Scots art

The kingdom of Dál Riata has been seen as a crossroads between the artistic styles of the Picts and those of Ireland, with which the Scots settlers in what is now Argyll kept close contact. This can be seen in representations found in excavations of the fortress of Dunadd, which combine Pictish and Irish elements.

Insular art

Insular art, or Hiberno-Saxon art, is the name given to the common style produced in Scotland, Britain and Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon forms.

Architecture

For the period after the departure of the Romans, there is evidence of a series of new forts, often smaller "nucleated" constructions compared with those from the Iron Age,[109] sometimes utilising major geographical features, as at Edinburgh and Dunbarton.[110] All the northern British peoples utilised different forms of fort and the determining factors in construction were local terrain, building materials, and politico-military needs.[111] The first identifiable king of the Picts, Bridei mac Maelchon had his base at the fort of Craig Phadrig near modern Inverness.[5] The Gaelic overkingdom of Dál Riata was probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd now near Kilmartin in Argyll and Bute.[112][10] The introduction of Christianity into Scotland from Ireland from the sixth century, led to the construction of the first churches. These may originally have been wooden, like that excavated at Whithorn,[113] but most of those for which evidence survives from this era are basic masonry-built churches, beginning on the west coast and islands and spreading south and east.[114]

Early chapels tended to have square-ended converging walls, similar to Irish chapels of this period.[115] Medieval parish church architecture in Scotland was typically much less elaborate than in England, with many churches remaining simple oblongs, without transepts and aisles, and often without towers. In the Highlands, they were often even simpler, many built of rubble masonry and sometimes indistinguishable from the outside from houses or farm buildings.[116] Monasteries also differed significantly from those on the continent, and were often an isolated collection of wooden huts surrounded by a wall.[90] At Eileach an Naoimh in the Inner Hebrides there are huts, a chapel, refectory, guest house, barns and other buildings. Most of these were made of timber and wattle construction and probably thatched with heather and turves. They were later rebuilt in stone, with underground cells and circular "beehive" huts like those used in Ireland. Similar sites have been excavated on Bute, Orkney and Shetland.[115] From the eighth century more sophisticated buildings emerged.[114]

Literature

Much of the earliest

Notes

- ISBN 0-521-54740-7, pp. 14–15.

- ISBN 1-58811-515-1, p. 215.

- ISBN 1-85285-195-3, p. 48.

- ISBN 0-416-82360-2, pp. 83–4.

- ^ ISBN 0-582-50578-X, p. 116.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 43–6.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 63–4.

- ISBN 0-7486-1232-7, p. 287.

- ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, p. 64.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0, pp. 161–2.

- ^ E. Campbell, "Were the Scots Irish?" in Antiquity, 75 (2001), pp. 285–92.

- ISBN 0-521-36395-0, pp. 159–160.

- ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 57–67.

- ^ ISBN 9781322571645.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 2.

- ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 8.

- ISBN 1-85264-047-2, p. 106.

- ISBN 1-4067-0896-8.

- ISBN 0-203-44730-1, pp. 75–7.

- ISBN 0-7486-1615-2, pp. 72–3.

- ISBN 0-203-44730-1, p. 78.

- ISBN 0-521-81335-2, p. 44.

- ISBN 0-521-81335-2, p. 89.

- ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, p. 31.

- ISBN 0-203-44730-1, pp. 78.

- ISBN 0-8160-7728-2, pp. 44–5.

- ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 10.

- ISBN 0-415-08396-6, p. 49.

- ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 9.

- ISBN 0-582-77292-3, p. 54.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-81335-2, p. 212.

- ISBN 0-631-22260-X, p. 220.

- ISBN 1-902930-16-9, p. 100.

- ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 122–6.

- ISBN 1-152-21572-8, p. 395.

- ISBN 0-8160-7728-2, p. 48.

- ISBN 0-19-210054-8, pp. 10–11.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-36291-1, p. 234.

- ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 175.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, pp. 224–5.

- ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 226.

- ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 227.

- ISBN 0-520-04669-2, p. 274.

- ISBN 0-582-77292-3, p. 53.

- ISBN 0-415-30149-1, p. 226.

- ISBN 0-7486-0641-6, pp. 37–41.

- ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 4.

- ISBN 0-7185-0084-9, p. 238.

- ISBN 978-0-9503904-1-3

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 17–20.

- ISBN 978-0-586-08248-5, p. 204.

- ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 230.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-54740-7, pp. 21–2.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-39552-6, pp. 82–4.

- ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 57–8.

- ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 369.

- ISBN 1-4051-0628-X, pp. 98.

- ISBN 0-87436-885-5, p. 136.

- ^ Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF), National Framework, Early Medieval (accessed May 2022).

- ^ Revealed: carved footprint marking Scotland's birth is a replica, The Herald, 22 September 2007.

- ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, p. 27.

- ^ ISBN 1-4051-0628-X, pp. 76–90.

- ISBN 0-582-50578-X, p. 125.

- ISBN 0-7486-0104-X.

- ISBN 0-903903-24-5, p. 56.

- ISBN 0-903903-24-5, pp. 248–9.

- ISBN 0-903903-24-5, p. 157.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0291-7, pp. 171–2.

- ISBN 0-7486-1736-1, p. 221.

- ISBN 0-14-191257-X, p. 6.

- ISBN 0-521-54740-7, pp. 129–30.

- ^ "Skuldelev 2 – The great longship", Viking Ship Museum, Roskilde, retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ N. A. M. Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain. Volume One 660–1649 (London: Harper, 1997) pp. 13–14.

- ISBN 0-14-025422-6, p. 184.

- ISBN 0-300-14485-7, p. 17.

- ISBN 0-9525029-1-7, p. 41.

- ISBN 0-903903-24-5, p. 63.

- ISBN 0-86054-138-X, p. 93.

- ISBN 1-872414-68-0(York: Council for British Archaeology, 1996), p. 20.

- ISBN 1-85285-154-6, p. 23.

- ISBN 0-521-54740-7, p. 306.

- ISBN 0-520-21859-0, pp. 79–80.

- ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 82–3.

- ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- ISBN 0-9512573-3-1, pp. 57 and 67–71.

- S2CID 162711350.

- ISBN 0-7134-8874-3, p. 77.

- ^ G. W. S. Barrow, "The childhood of Scottish Christianity: a note on some place-name evidence", in Scottish Studies, 27 (1983), pp. 1–15.

- ISBN 0-7486-1232-7, p. 89.

- ^ ISBN 0-88920-166-8, pp. 77–89.

- ISBN 0-19-922665-2, p. 698.

- ISBN 0-14-013627-4.

- ISBN 0-521-54740-7, p. 307.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 310–11.

- ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 67–8.

- ISBN 1-84383-125-2, pp. 207–35.

- ISBN 0-520-21859-0, p. 170.

- ISBN 0-19-289324-6, p. 211.

- ISBN 0-7486-0291-7, pp. 161–5.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0641-6, pp. 7–8.

- ^ ISBN 0-7141-0554-6, pp. 26–8.

- ISBN 0-85263-874-4, p. 37.

- ISBN 0-521-36395-0, pp. 331–2.

- ^ A. Lane, "Citadel of the first Scots", British Archaeology, 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ISBN 0-7141-0554-6, pp. 109–113.

- ISBN 0-333-37185-2, pp. 244–7.

- ISBN 0-300-06493-4, pp. 85 and 90.

- ^ G. Henderson, Early Medieval Art (London: Penguin, 1972), pp. 63–71.

- OCLC 560286204

- ISBN 0-521-54740-7, p. 34.

- ISBN 978-0-903903-24-0, p. 190.

- ^ Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF), Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll (accessed May 2022).

- ISBN 0-7486-2179-2, p. 1.

- ^ ISBN 1-904320-02-3, pp. 22–3.

- ^ ISBN 0-85263-748-9, p. 8.

- ISBN 0-415-02992-9, p. 117.

- ISBN 0-313-30054-2, p. 508.

- ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 999.

- ISBN 0-7486-1615-2, p. 94.

- ISBN 1-4051-1313-8, p. 108.

References

- ISBN 978-0-903903-24-0

- Armit, Ian (2005), Celtic Scotland (2nd ed.), London: Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-8949-1

- Breeze, David (2006), Roman Scotland: Frontier Country (2nd ed.), London: Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-8995-8

- Crawford, Barbara (1987), Scandinavian Scotland, Leicester: Leicester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7185-1282-8

- Foster, Sally M. (2004), Picts, Gaels and Scots: Early Historic Scotland (2nd ed.), London: Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-8874-6

- Harding, D. W. (2004), The Iron Age in Northern Britain. Celts and Romans, Natives and Invaders, Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30150-3

- Higham, N. J. (1993), The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100, Stroud: Sutton, ISBN 978-0-86299-730-4

- McNeill, Peter G. B.; MacQueen, Hector L., eds. (2000), Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (reprinted with corrections ed.), Edinburgh: The Scottish Medievalists and Department of Geography, University of Edinburgh, ISBN 978-0-9503904-1-3

- Nicolaisen, W. F. H. (2001), Scottish Place-names: Their Study and Significance (2nd ed.), Edinburgh: John Donald, ISBN 978-0-85976-556-5

- ISBN 978-0-500-02100-2

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1989) [1984], Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-0100-4

- Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred; Kirby, D.P. (1991), A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain, London: Seaby, ISBN 978-1-85264-047-7

- ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5

- ISBN 978-0-582-77292-2