Scotland in the modern era

| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

Scotland in the modern era, from the end of the

Scotland made a major contribution to the intellectual life of Europe, particularly in the

In the 20th century, Scotland played a major role in the British and allied effort in the two world wars and began to suffer a sharp industrial decline, going through periods of considerable political instability. The decline was particularly acute in the second half of the 20th century, but was compensated for to a degree by the development of an extensive oil industry, technological manufacturing and a growing service sector. This period also increasing debates about the place of Scotland within the United Kingdom, the rise of the Scottish National Party and after a referendum in 1999 the establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament.

Late 18th century and 19th century

With the advent of the Union with England and the demise of Jacobitism, thousands of Scots, mainly Lowlanders, took up positions of power in politics, civil service, the army and navy, trade, economics, colonial enterprises and other areas across the nascent British Empire. Historian Neil Davidson notes that "after 1746 there was an entirely new level of participation by Scots in political life, particularly outside Scotland". Davidson also states that "far from being 'peripheral' to the British economy, Scotland – or more precisely, the Lowlands – lay at its core".[1]

Politics

Scottish politics in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century was dominated by the

The main unit of local government was the parish, and since it was also part of the church, the elders imposed public humiliation for what the locals considered immoral behaviour, including fornication, drunkenness, wife beating, cursing and Sabbath breaking. The main focus was on the poor and the landlords ("lairds") and gentry, and their servants, were not subject to the parish's discipline. The policing system weakened after 1800 and disappeared in most places by the 1850s.[8]

Enlightenment

In the 18th century, the Scottish Enlightenment brought the country to the front of intellectual achievement in Europe. Perhaps the poorest country in Western Europe in 1707, Scotland reaped the economic benefits of

The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson, who held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1729 to 1746. A moral philosopher who produced alternatives to the ideas of Thomas Hobbes, one of his major contributions to world thought was the utilitarian and consequentialist principle that virtue is that which provides, in his words, "the greatest happiness for the greatest numbers". Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by his proteges David Hume and Adam Smith.[11]

Hume became a major figure in the

Religion

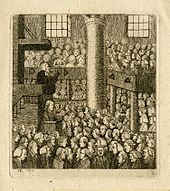

The late 18th and 19th centuries saw a fragmentation of the

By the mid-18th century, Catholicism had been reduced to the fringes of the country, particularly the

Industrial Revolution

During the

Linen was Scotland's premier industry in the 18th century and formed the basis for the later cotton, jute,

From about 1790 textiles became the most important industry in the west of Scotland, especially the spinning and weaving of cotton, which flourished until in 1861 the American Civil War cut off the supplies of raw cotton.[32] The industry never recovered, but by that time Scotland had developed heavy industries based on its coal and iron resources. The invention of the hot blast for smelting iron (1828) revolutionised the Scottish iron industry. As a result, Scotland became a centre for engineering, shipbuilding and the production of locomotives. Toward the end of the 19th century, steel production largely replaced iron production.[33]

Coal mining became a major industry, and continued to grow into the 20th century, producing the fuel to heat homes, factories and drive steam engines, locomotives and steamships. By 1914 there were 1,000,000 coal miners in Scotland. The stereotype emerged early on of Scottish colliers as brutish, non-religious and socially isolated serfs;[34] that was an exaggeration, for their life style resembled coal miners everywhere, with a strong emphasis on masculinity, egalitarianism, group solidarity, and support for radical labour movements.[35]

Britain was the world leader in the construction of railways, and their use to expand trade and coal supplies. The first successful locomotive-powered line in Scotland, between Monkland and Kirkintilloch, opened in 1831.[36] Not only was good passenger service established by the late 1840s, but an excellent network of freight lines reduce the cost of shipping coal, and made products manufactured in Scotland competitive throughout Britain. For example, railways opened the London market to Scottish beef and milk. They enabled the Aberdeen Angus to become a cattle breed of worldwide reputation.[37][38]

Urbanisation

Scotland was already one of the most urbanised societies in Europe by 1800.

The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.[43] The companies attracted rural workers, as well as immigrants from Catholic Ireland, by inexpensive company housing that was a dramatic move upward from the inner-city slums. This paternalistic policy led many owners to support government sponsored housing programs as well as self-help projects among the respectable working class.[44]

Highlands

Modern historians suggest that due to economic and social change, the clan system in the highlands was already declining by the time of the failed

The reality of the Highlands was that of an agriculturally marginal region, with only an estimated 9% of its land suitable for arable production.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the few successful industries of the Highlands went into decline: cattle prices fell and the kelp industry virtually disappeared over a few years.[56]: 370–371 [57]: 187-191

Crofting communities had become common in the Islands and the Western Highlands. Population growth had continued, causing overcrowding: crofts were subdivided, giving less land per person on which to grow food. Their occupiers were dependent on the highly productive potato for survival. When

The unequal

Emigration

The population of Scotland grew steadily in the 19th century, from 1,608,000 in the census of 1801 to 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901.

Education

A legacy of the Reformation in Scotland was the aim of having a school in every parish, which was underlined by an act of the Scottish parliament in 1696 (reinforced in 1801). In rural communities these obliged local landowners (heritors) to provide a schoolhouse and pay a schoolmaster, while ministers and local presbyteries oversaw the quality of the education. In many Scottish towns, burgh schools were operated by local councils.[69] One of the effects of this extensive network of schools was the growth of the "democratic myth" in the 19th century, which created the widespread belief that many a "lad of pairts" had been able to rise up through the system to take high office and that literacy was much more widespread in Scotland than in neighbouring states, particularly England.[70] Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic, short and attendance was not compulsory.[71]

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the Disruption of 1843 all undermined the tradition of parish schools. From 1830 the state began to fund buildings with grants, then from 1846 it was funding schools by direct sponsorship, and in 1872 Scotland moved to a system like that in England of state-sponsored largely free schools, run by local school boards.[71] Overall administration was in the hands of the Scotch (later Scottish) Education Department in London.[72] Education was now compulsory from five to thirteen and many new board schools were built. Larger urban school boards established "higher grade" (secondary) schools as a cheaper alternative to the burgh schools. The Scottish Education Department introduced a Leaving Certificate Examination in 1888 to set national standards for secondary education and in 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded national system of free basic education and common examinations.[70]

The five Scottish universities had been oriented to clerical and legal training, after the religious and political upheavals of the 17th century they recovered with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry. It helped the universities to become major centres of medical education and to put Scotland at the forefront of Enlightenment thinking.[70] In the mid 19th century, the historic University of Glasgow became a leader in British higher education by providing the educational needs of youth from the urban and commercial classes, as well as the upper class. It prepared students for non-commercial careers in government, the law, medicine, education, and the ministry and a smaller group for careers in science and engineering.[73] Scottish universities would admit women from 1892.[70]

Literature

Although Scotland increasingly adopted the English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation.

Robert Burns and Walter Scott were highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.[77] Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[78] It launched a highly successful career that probably more than any other helped define and popularise Scottish cultural identity.[79]

In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations. Robert Louis Stevenson's work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and played a major part in developing the historical adventure in books like Kidnapped and Treasure Island. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories helped found the tradition of detective fiction. The "kailyard tradition" at the end of the century, brought elements of fantasy and folklore back into fashion as can be seen in the work of figures like J. M. Barrie, most famous for his creation of Peter Pan and George MacDonald whose works including Phantasies played a major part in the creation of the fantasy genre.[80]

Art and architecture

Scotland in this era produced some of the most significant British artists and architects. The influence of Italy was particularly significant, with over fifty Scottish artists and architects known to have travelled there in the period 1730–80.[81] Many painters of the early part of the eighteenth century remained largely artisans, like the members of the Norie family, James (1684–1757) and his sons, who painted the houses of the peerage with Scottish landscapes that were pastiches of Italian and Dutch landscapes.[82] The painters Allan Ramsay (1713–84),[83] Gavin Hamilton (1723–98),[84] the brothers John (1744–1768/9) and Alexander Runciman (1736–85),[85] Jacob More (1740–93)[82] and David Allan (1744–96),[86] mostly began in the tradition of the Nories, but were artists of European significance, spending considerable portions of their careers outside Scotland, and were to varying degree influenced by forms of Neoclassicism.

The shift in attitudes to a romantic view of the Highlands at the end of the 18th century had a major impact on Scottish art.

Scotland produced some of the most significant British architects of the 18th century, including: Colen Campbell (1676–1729), James Gibbs (1682–1754), James (1732–94), John (1721–92) and Robert Adam (1728–92) and William Chambers (1723–96), who all created work that to some degree looked to classical models. Edinburgh's New Town was the focus of this classical building boom in Scotland. From the mid-eighteenth century it was laid out according to a plan of rectangular blocks with open squares, drawn up by James Craig. This classicism, together with its reputation as a major centre of the Enlightenment, resulted in the city being nicknamed "The Athens of the North".[96] However, the centralisation of much of the government administration, including the king's works, in London, meant that a number of Scottish architects spent most of all of their careers in England, where they had a major impact on Georgian architecture.[97]

Early 20th century

In the 20th century, Scotland made a major contribution to the British participation in the two world wars and suffered relative economic decline, which only began to be offset with the exploitation of North Sea Oil and Gas from the 1970s and the development of new technologies and service industries. This was mirrored by a growing sense of cultural and political distinctiveness which, towards the end of the century, culminated in the establishment of a separate Scottish Parliament within the confines of the United Kingdom.

Before the First World War 1901–13

In the

The years before the First World War were the golden age of the inshore fisheries. Landings reached new heights, and Scottish catches dominated Europe's herring trade, accounting for a third of the British catch. High productivity came about thanks to the transition to more productive steam-powered boats, while the rest of Europe's fishing fleets were slower because they were still powered by sails.[100] However, in general the Scottish economy stagnated leading to growing unemployment and political agitation among industrial workers.[98]

First World War 1914–18

Scotland played a major role in the British effort in the First World War.

Inter-war period 1919–38

After World War I the Liberal Party began to disintegrate. As the Liberals splintered Labour emerged to become the party of progressive politics in Scotland, gaining a solid following among working classes of the urban lowlands, and as a result the Unionists were able to gain most of the votes of the middle classes, who now feared

The interwar years were marked by economic stagnation in rural and urban areas, and high unemployment. Thoughtful Scots pondered their declension, as the main social indicators such as poor health, bad housing, and long-term mass unemployment, pointed to terminal social and economic stagnation at best, or even a downward spiral. The heavy dependence on obsolescent heavy industry and mining was a central problem, and no one offered workable solutions. The despair reflected what Finlay (1994) describes as a widespread sense of hopelessness that prepared local business and political leaders to accept a new orthodoxy of centralised government economic planning when it arrived during the Second World War.[109]

The shipbuilding industry had expanded by a third during the war and had expected continued prosperity, but instead it shrank drastically. A serious depression hit the economy by 1922 and it did not fully recover until 1939.[110] The most skilled craftsmen were especially hard hit, because there were few alternative uses for their specialised skills. The yards went into a long period of decline, interrupted only by the Second World War's temporary expansion.[111] The war had seen the emergence of a radical movement led by militant trades unionists. John MacLean became a key political figure in what became known as Red Clydeside, and in January 1919, the British Government, fearful of a revolutionary uprising, deployed tanks and soldiers in central Glasgow. Formerly a Liberal stronghold, the industrial districts switched to Labour by 1922, with a base in the Irish Catholic working class districts. Women were especially active in building neighbourhood solidarity on housing and rent issues. However, the "Reds" operated within the Labour Party and had little influence in Parliament; in the face of heavy unemployment the workers' mood changed to passive despair by the late 1920s.[112]

Emigration of young people continued apace with 400,000 Scots, ten per cent of the population, estimated to have left the country between 1921 and 1931.[113] The economic stagnation was only one factor; other push factors included a zest for travel and adventure, and the pull factors of better job opportunities abroad, personal networks to link into, and the basic cultural similarity of the United States, Canada, and Australia. Government subsidies for travel and relocation facilitated the decision to emigrate. Personal networks of family and friends who had gone ahead and wrote back, or sent money, prompted emigrants to follow.[114]

Scottish renaissance

In the early 20th century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature and art, influenced by

In art, the first significant group to emerge in the 20th century were the

Second World War 1939–45

The Second World War brought renewed prosperity, despite extensive bombing of cities by the Luftwaffe. It saw the invention of radar by Robert Watson-Watt, which was invaluable in the Battle of Britain, as was the leadership at RAF Fighter Command of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding.[120]

As in World War I,

Scottish industry came out of the depression slump by a dramatic expansion of its industrial activity, absorbing unemployed men and many women as well. The shipyards were the centre of more activity, but many smaller industries produced the machinery needed by the British bombers, tanks and warships.[113] Agriculture prospered, as did all sectors except for coal mining, which was operating mines near exhaustion. Real wages, adjusted for inflation, rose 25 per cent, and unemployment temporarily vanished. Increased income, and the more equal distribution of food, obtained through a tight rationing system, dramatically improved the health and nutrition; the average height of 13-year-olds in Glasgow increased by 2 inches.[125]

Prime Minister

Postwar 1946–present

Postwar politics

In this period the Labour Party usually won most Scottish parliamentary seats, losing this dominance briefly to the

Economics

After World War II, Scotland's economic situation became progressively worse due to overseas competition, inefficient industry, and industrial disputes.

Twentieth-century religion

In the 20th century existing Christian denominations were joined by other organisations, including the

Twentieth-century education

The Scottish education system underwent radical change and expansion in the 20th century. In 1918

New literature

Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher

Modern art

Important post-war artists included

Notes

References

- ISBN 0-7453-1608-5, pp. 94–5.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0839-7, pp. 64–5.

- ISBN 1-905641-28-1, pp. 37–40.

- ISBN 1-4094-0922-8, p. 39.

- ISBN 0-19-726331-3, p. 52.

- ISBN 0-521-77736-4, p. 183.

- ISBN 0-7190-1791-2, p. 144.

- ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 84–89.

- ISBN 0-609-80999-7.

- ^ José Manuel Barroso (28 November 2006), "The Scottish enlightenment and the challenges for Europe in the 21st century; climate change and energy", EUROPA: Enlightenment Lecture Series, Edinburgh University, archived from the original on 22 September 2007, retrieved 22 March 2012

- ^ a b "The Scottish enlightenment and the challenges for Europe in the 21st century; climate change and energy", The New Yorker, 11 October 2004, archived from the original on 6 June 2011, retrieved 6 February 2016

- ^ a b M. Magnusson (10 November 2003), "Review of James Buchan, Capital of the Mind: how Edinburgh Changed the World", New Statesman, archived from the original on 6 June 2011, retrieved 27 April 2014

- ^ A. Swingewood, "Origins of Sociology: The Case of the Scottish Enlightenment," The British Journal of Sociology, vol. 21, no. 2 (June 1970), pp. 164–80 in JSTOR.

- ISBN 0-415-06164-4.

- ISBN 0-7382-0692-X, pp. 117–43.

- ISBN 1-84018-611-9.

- ^ ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–17.

- ^ ISBN 1-85728-481-X, p. 91.

- ISBN 0-7623-1298-X, pp. 23–4.

- ^ Henry Hamilton, An Economic History of Scotland in the Eighteenth Century (1963).

- JSTOR 4248011

- ^ T. M. Devine, "The Colonial Trades and Industrial Investment in Scotland, c. 1700–1815," Economic History Review, Feb 1976, vol. 29 (1), pp. 1–13.

- ^ R. H. Campbell, "The Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. II: The Economic Consequences," Economic History Review, April 1964 vol. 16, pp. 468–477 in JSTOR.

- ^ T. M. Devine, "An Eighteenth-Century Business Élite: Glasgow-West India Merchants, c 1750–1815," Scottish Historical Review, April 1978, vol. 57 (1), pp. 40–67.

- ^ Louise Miskell and C. A. Whatley, "'Juteopolis' in the Making: Linen and the Industrial Transformation of Dundee, c. 1820–1850," Textile History, Autumn 1999, vol. 30 (2), pp. 176–98.

- ^ Alastair J. Durie, "The Markets for Scottish Linen, 1730–1775," Scottish Historical Review vol. 52, no. 153, Part 1 (April 1973), pp. 30–49 in JSTOR.

- ^ Alastair Durie, "Imitation in Scottish Eighteenth-Century Textiles: The Drive to Establish the Manufacture of Osnaburg Linen," Journal of Design History, 1993, vol. 6 (2), pp. 71–6.

- ^ C. A. Malcolm, The History of the British Linen Bank (1950).

- ISBN 0-7486-0757-9.

- ISBN 0-19-822281-5, p. 344.

- ^ T. Cowen and R. Kroszner, "Scottish Banking before 1845: A Model for Laissez-Faire?", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 21, (2), (May 1989), pp. 221–31 in JSTOR.

- ^ W. O. Henderson, The Lancashire Cotton Famine 1861–65 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1934), p. 122.

- ISBN 0-521-57643-1, p. 51.

- ^ C. A. Whatley, "Scottish 'collier serfs', British coal workers? Aspects of Scottish collier society in the eighteenth century", Labour History Review, Fall 1995, vol. 60 (2), pp. 66–79.

- ISBN 0-7546-0191-9.

- ISBN 3-86195-239-4, p. 223.

- ISBN 0-7486-0102-3, pp. 17–52.

- ^ W. Vamplew, "Railways and the Transformation of the Scottish Economy", Economic History Review, Feb 1971, vol. 24 (1), pp. 37–54.

- ^ William Ferguson, The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest (1998) online edition.

- ^ I.H. Adams, The Making of Urban Scotland (Croom Helm, 1978).

- ISBN 0-7190-6497-X, pp. 215–23.

- ^ J. Shields, Clyde Built: a History of Ship-Building on the River Clyde (Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1949).

- ISBN 0-7190-4101-5, p. 43.

- ^ J. Melling, "Employers, industrial housing and the evolution of company welfare policies in Britain's heavy industry: west Scotland, 1870–1920", International Review of Social History, Dec 1981, vol. 26 (3), pp. 255–301.

- ISBN 0-8078-4913-8, p. 41.

- ISBN 1-902930-29-0, pp. 193–5.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-638-81651-9.

- ISBN 0-8387-5526-7, pp. 75–6.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-1071-6.

- ISBN 978-1-899820-79-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0241304105.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-78027-165-1.

- ISBN 978-0709922599.

- ISBN 978-1-906566-23-4.

- ISBN 9780773511569.

- ISBN 9780712698931.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7190-9076-9.

- ISBN 1-904607-42-X.

- ISBN 0-670-88811-7

- ^ J. Hunter (1974), "The Emergence of the Crofting Community: The Religious Contribution 1798–1843", Scottish Studies, 18: 95–111

- ^ I. Bradley (December 1987), "'Having and Holding': The Highland Land War of the 1880s", History Today, 37: 23–28

- ^ A. K. Cairncross, The Scottish Economy: A Statistical Account of Scottish Life by Members of the Staff of Glasgow University (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1953), p. 10.

- ISBN 0-14-026367-5, p. xxxii.

- ^ J. H. Morrison, John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

- ^ J. M. Bunsted, "Scots", Canadian Encyclopedia, archived from the original on 23 May 2011, retrieved 20 September 2017

- ISBN 1-921410-21-3.

- ^ "Scots", Te Ara, archived from the original on 16 May 2011, retrieved 22 November 2011

- ^ "School education prior to 1873", Scottish Archive Network, 2010, archived from the original on 28 September 2011, retrieved 1 November 2013

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 219–28.

- ^ ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 91–100.

- ^ "Education records", National Archive of Scotland, 2006, archived from the original on 31 August 2011, retrieved 18 November 2011

- ^ Paul L. Robertson, "The Development of an Urban University: Glasgow, 1860–1914", History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1990, vol. 30 (1), pp. 47–78.

- ISBN 0060558881

- ISBN 0060558881

- ^ D. Thomson (1952), The Gaelic Sources of Macpherson's "Ossian", Aberdeen: Oliver & Boyd

- S2CID 144358210

- ISBN 978-0754661429

- ISBN 0745316085

- ^ "Cultural Profile: 19th and early 20th century developments", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 30 September 2011

- ISBN 978-0-19-162243-4.

- ^ ISBN 1409426181, p. 153.

- ^ "Alan Ramsey", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ "Gavin Hamilton", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ISBN 019953294X, p. 554.

- ISBN 061825210X, pp. 34–5.

- ^ ISBN 0521642027, pp. 151–3.

- ISBN 0300058330, p. 293.

- ISBN 1906261083, p. 84.

- ISBN 019953294X, p. 433.

- ISBN 1550021591, p. 401.

- ISBN 1119992761, p. 23.

- ISBN 0806132531, p. 136.

- ISBN 019953294X, p. 195.

- ISBN 0486417948, pp. 283–4.

- ^ "Old and New Towns of Edinburgh – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-0849-2, p. 73.

- ^ ISBN 1-902930-16-9, p. 45.

- ISBN 0-7190-4510-X, p. 60.

- ^ C. Reid, "Intermediation, Opportunism and the State Loans Debate in Scotland's Herring Fisheries before World War I," International Journal of Maritime History, June 2004, vol. 16 (1), pp. 1–26.

- ISBN 1-86232-056-X.

- ^ D. Daniel, "Measures of enthusiasm: new avenues in quantifying variations in voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914 – December 1915", Local Population Studies, Spring 2005, Issue 74, pp. 16–35.

- ISBN 0-7190-1737-8, p. 11.

- ISBN 0-14-026367-5, p. 426.

- ^ ISBN 981-234-950-2, p. 49.

- ^ D. Coetzee, "A life and death decision: the influence of trends in fertility, nuptiality and family economies on voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914 to December 1915", Family and Community History, Nov 2005, vol. 8 (2), pp. 77–89.

- ISBN 0-87021-607-4, p. 231.

- ^ ISBN 0-582-35674-1, p. 93.

- ^ R. J. Finlay, "National identity in crisis: politicians, intellectuals and the 'end of Scotland', 1920–1939," History, June 1994, vol. 79, (256), pp. 242–59.

- ^ N. K. Buxton, "Economic growth in Scotland between the Wars: the role of production structure and rationalization", Economic History Review, Nov 1980, vol. 33 (4), pp. 538–55.

- ISBN 0-8476-6013-3, pp. 258–78.

- ISBN 0-85976-516-4.

- ^ ISBN 981-234-950-2, p. 51.

- ^ A. McCarthy, "Personal Accounts of Leaving Scotland, 1921–1954", Scottish Historical Review,' Oct 2004, vol. 83 (2), Issue 216, pp. 196–215.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Scottish 'Renaissance' and beyond", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 30 September 2011

- ^ "The Scottish Colourists", Visit Scotland.com, archived from the original on 29 April 2008, retrieved 7 May 2010

- ISBN 019953294X, p. 575.

- ^ ISBN 0748620273, p. 173.

- ^ D. Macmillan, "Review: Painters in Parallel: William Johnstone & William Gillies", Scotsman.com, 19 January 2012, retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ISBN 1-86197-308-X, pp. 162–97.

- ISBN 0-405-12209-8, p. 87.

- ^ J. Creswell, Sea Warfare 1939–1945 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2nd edn., 1967), p. 52.

- ISBN 1-59921-321-4.

- ISBN 0-7551-0041-7, p. 15.

- ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 549–50.

- ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 551–2.

- ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 553–4.

- ISBN 0-7190-1997-4, pp. 153 and 174.

- ISBN 0-7190-4510-X, p. 46.

- ISBN 0-7146-5223-7, p. 33.

- ^ "The poll tax in Scotland 20 years on", BBC News, 1 April 2009, archived from the original on 28 July 2011, retrieved 19 November 2011

- ^ "Devolution to Scotland", BBC News, 14 October 2002, archived from the original on 23 June 2011, retrieved 14 November 2006

- ^ "The New Scottish Parliament at Holyrood" (PDF). Audit Scotland, Sep 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- ^ A. Black (18 May 2011), "Scottish election: SNP profile", BBC News, archived from the original on 20 May 2011, retrieved 21 June 2018

- ISBN 0-7486-1085-5, p. 255.

- ^ Shepherd, Mike (2015). Oil Strike North Sea: A first-hand history of North Sea oil. Luath Press.

- ISBN 0-262-72011-6, p. 317.

- Scottish Economic and Social History, 1995, vol. 15 (1), pp. 66–84.

- ISBN 1-86197-308-X, ch. 9.

- ^ H. Stewart (6 May 2007), "Celtic Tiger Burns Brighter at Holyrood", Guardian.co.uk, archived from the original on 6 December 2008, retrieved 25 April 2008

- ^ "Religion (detailed)" (PDF). Scotland's Census 2011. National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 132–40.

- ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 62–73.

- ISBN 0-330-33550-2

- ^ The Scots Makar, The Scottish Government, 16 February 2004, archived from the original on 4 February 2012, retrieved 28 October 2007

- ISBN 978-0-906391-46-4

- ^ "Duffy reacts to new Laureate post", BBC News, 1 May 2009, archived from the original on 30 October 2011

- ^ ISBN 1119992761, p. 25.

- ISBN 0754661245, p. 58.

- ISBN 019953294X, p. 255.

- ISBN 1858288878, p. 114.

- ISBN 019953294X, p. 657.

- ISBN 0816646538, p. 61.

- ^ C. Higgins (17 October 2011), "Glasgow's Turner connection", Guardian.co.uk, archived from the original on 6 April 2012

- ISBN 978-1-84708-693-8.