Sea anemone

| Sea anemone Temporal range: Upper Cambrian to Present

| |

|---|---|

| |

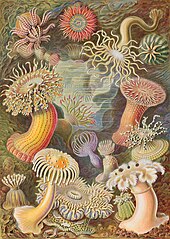

| A selection of sea anemones, painted by Giacomo Merculiano, 1893 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hexacorallia |

| Order: | Actiniaria Hertwig, 1882 |

| Suborders | |

| Diversity | |

46 families

| |

Sea anemones (/əˈnɛm.ə.ni/ ə-NEM-ə-nee) are a group of predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the Anemone, a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classified in the phylum Cnidaria, class Anthozoa, subclass Hexacorallia. As cnidarians, sea anemones are related to corals, jellyfish, tube-dwelling anemones, and Hydra. Unlike jellyfish, sea anemones do not have a medusa stage in their life cycle.

A typical sea anemone is a single polyp attached to a hard surface by its base, but some species live in soft sediment, and a few float near the surface of the water. The polyp has a columnar trunk topped by an oral disc with a ring of tentacles and a central mouth. The tentacles can be retracted inside the body cavity or expanded to catch passing prey.[clarification needed] They are armed with cnidocytes (stinging cells). In many species, additional nourishment comes from a symbiotic relationship with single-celled dinoflagellates, with zooxanthellae, or with green algae, zoochlorellae, that live within the cells. Some species of sea anemone live in association with clownfish, hermit crabs, small fish, or other animals to their mutual benefit.

Sea anemones breed by liberating sperm and eggs through the mouth into the sea. The resulting fertilized eggs develop into planula larvae which, after being planktonic for a while, settle on the seabed and develop directly into juvenile polyps. Sea anemones also breed asexually, by breaking in half or into smaller pieces which regenerate into polyps. Sea anemones are sometimes kept in reef aquariums; the global trade in marine ornamentals for this purpose is expanding and threatens sea anemone populations in some localities, as the trade depends on collection from the wild.

Anatomy

1. Tentacles 2. Mouth 3. Retracting muscles 4. Gonads 5. acontial filaments 6. Pedal disk 7. Ostium 8. Coelenteron 9. Sphincter muscle 10. Mesentery 11. Column 12. Pharynx

A typical sea anemone is a sessile polyp attached at the base to the surface beneath it by an adhesive foot, called a basal or pedal disc, with a column-shaped body topped by an oral disc. Most are from 1 to 5 cm (0.4 to 2.0 in) in diameter and 1.5 to 10 cm (0.6 to 3.9 in) in length, but they are inflatable and vary greatly in dimensions. Some are very large; Urticina columbiana and Stichodactyla mertensii can both exceed 1 metre (3.3 ft) in diameter and Metridium farcimen a metre in length.[1] Some species burrow in soft sediment and lack a basal disc, having instead a bulbous lower end, the physa, which anchors them in place.[1]

The column or trunk is generally more or less cylindrical and may be plain and smooth or may bear specialised structures; these include solid papillae (fleshy protuberances), adhesive papillae, cinclides (slits), and small protruding vesicles. In some species the part immediately below the oral disc is constricted and is known as the capitulum. When the animal contracts, the oral disc, tentacles and capitulum fold inside the pharynx and are held in place by a strong sphincter muscle part way up the column. There may be a fold in the body wall, known as a parapet, at this point, and this parapet covers and protects the anemone when it is retracted.[1]

The oral disc has a central mouth, usually slit-shaped, surrounded by one or more whorls of tentacles. The ends of the slit lead to grooves in the wall of the pharynx known as

Many sea anemones also have acontia, thin filaments covered in cnidae that can be ejected and retracted for defence.

hell's-fire anemone

The venom is a mix of

Digestive system

Sea anemones have what can be described as an incomplete gut; the gastrovascular cavity functions as a stomach and possesses a single opening to the outside, which operates as both a mouth and anus. Waste and undigested matter is excreted through this opening. The mouth is typically slit-like in shape, and bears a groove at one or both ends. The groove, termed a siphonoglyph, is ciliated, and helps to move food particles inwards and circulate water through the gastrovascular cavity.[6]

The mouth opens into a flattened pharynx. This consists of an in-folding of the body wall, and is therefore lined by the animal's epidermis. The pharynx typically runs for about one third the length of the body before opening into the gastrovascular cavity that occupies the remainder of the body.[1]

The gastrovascular cavity itself is divided into a number of chambers by mesenteries radiating inwards from the body wall. Some of the mesenteries form complete partitions with a free edge at the base of the pharynx, where they connect, but others reach only partway across. The mesenteries are usually found in multiples of twelve, and are symmetrically arranged around the central lumen. They have stomach lining on both sides, separated by a thin layer of mesoglea, and include filaments of tissue specialised for secreting digestive enzymes. In some species, these filaments extend below the lower margin of the mesentery, hanging free in the gastrovascular cavity as thread-like acontial filaments. These acontia are armed with nematocysts and can be extruded through cinclides, blister-like holes in the wall of the column, for use in defence.[6]

Musculature and nervous system

A primitive nervous system, without centralization, coordinates the processes involved in maintaining homeostasis, as well as biochemical and physical responses to various stimuli. There are two nerve nets, one in the epidermis and one in the gastrodermis; these unite at the pharynx, the junctions of the septa with the oral disc and the pedal disc, and across the mesogloea. No specialized sense organs are present, but sensory cells include nematocytes and chemoreceptors.[1]

The muscles and nerves are much simpler than those of most other animals, although more specialised than in other cnidarians, such as corals. Cells in the outer layer (epidermis) and the inner layer (gastrodermis) have microfilaments that group into contractile fibers. These fibers are not true muscles because they are not freely suspended in the body cavity as they are in more developed animals. Longitudinal fibres are found in the tentacles and oral disc, and also within the mesenteries, where they can contract the whole length of the body. Circular fibers are found in the body wall and, in some species, around the oral disc, allowing the animal to retract its tentacles into a protective sphincter.[6]

Since the anemone lacks a rigid skeleton, the contractile cells pull against the fluid in the gastrovascular cavity, forming a hydrostatic skeleton. The anemone stabilizes itself by flattening its pharynx, which acts as a valve, keeping the gastrovascular cavity at a constant volume and making it rigid. When the longitudinal muscles relax, the pharynx opens and the cilia lining the siphonoglyphs beat, wafting water inwards and refilling the gastrovascular cavity. In general, the sea anemone inflates its body to extend its tentacles and feed, and deflates it when resting or disturbed. The inflated body is also used to anchor the animal inside a crevice, burrow or tube.[1]

Life cycle

Unlike other cnidarians, anemones (and other

The sexes in sea anemones are separate in some species, while other species are

The brooding anemone (Epiactis prolifera) is gynodioecious, starting life as a female and later becoming hermaphroditic, so that populations consist of females and hermaphrodites.[10] As a female, the eggs can develop parthenogenetically into female offspring without fertilisation, and as a hermaphrodite, the eggs are routinely self-fertilised.[8] The larvae emerge from the anemone's mouth and tumble down the column, lodging in a fold near the pedal disc. Here they develop and grow, remaining for about three months before crawling off to start independent lives.[8]

Sea anemones have great powers of regeneration and can reproduce asexually, by

The sea anemone Aiptasia diaphana displays sexual plasticity. Thus asexually produced clones derived from a single founder individual can contain both male and female individuals (ramets). When eggs and sperm (gametes) are formed, they can produce zygotes derived from "selfing" (within the founding clone) or out-crossing, which then develop into swimming planula larvae.[15] Anemones tend to grow and reproduce relatively slowly. The magnificent sea anemone (Heteractis magnifica), for example, may live for decades, with one individual surviving in captivity for eighty years.[16]

Behaviour and ecology

Movement

A sea anemone is capable of changing its shape dramatically. The column and tentacles have longitudinal, transverse and diagonal sheets of muscle and can lengthen and contract, as well as bend and twist. The gullet and mesenteries can evert (turn inside out), or the oral disc and tentacles can retract inside the gullet, with the sphincter closing the aperture; during this process, the gullet folds transversely and water is discharged through the mouth.[17]

Locomotion

Although some species of sea anemone burrow in soft sediment, the majority are mainly

The sea onion

Feeding and diet

Sea anemones are typically

Mutualistic relationships

Although not plants and therefore incapable of photosynthesis themselves, many sea anemones form an important facultative mutualistic relationship with certain single-celled algae species that reside in the animals' gastrodermal cells, especially in the tentacles and oral disc. These algae may be either zooxanthellae, zoochlorellae or both. The sea anemone benefits from the products of the algae's photosynthesis, namely oxygen and food in the form of glycerol, glucose and alanine; the algae in turn are assured a reliable exposure to sunlight and protection from micro-feeders, which the sea anemones actively maintain. The algae also benefit by being protected by the sea anemone's stinging cells, reducing the likelihood of being eaten by herbivores. In the aggregating anemone (Anthopleura elegantissima), the colour of the anemone is largely dependent on the proportions and identities of the zooxanthellae and zoochlorellae present.[1] The hidden anemone (Lebrunia coralligens) has a whorl of seaweed-like pseudotentacles, rich in zooxanthellae, and an inner whorl of tentacles. A daily rhythm sees the pseudotentacles spread widely in the daytime for photosynthesis, but they are retracted at night, at which time the tentacles expand to search for prey.[26]

Several species of fish and

Two of the more unusual relationships are those between certain anemones (such as Adamsia, Calliactis and Neoaiptasia) and hermit crabs or snails, and Bundeopsis or Triactis anemones and Lybia boxing crabs. In the former, the anemones live on the shell of the hermit crab or snail.[31][33][34][35] In the latter, the small anemones are carried in the claws of the boxing crab.[31][36]

Habitats

Sea anemones are found in both deep oceans and shallow coastal waters worldwide. The greatest diversity is in the tropics, although there are many species adapted to relatively cold waters. The majority of species cling on to rocks, shells or submerged timber, often hiding in cracks or under seaweed, but some burrow into sand and mud, and a few are pelagic.[1]

Relationship with humans

Sea anemones and their attendant anemone fish can make attractive aquarium exhibits, and both are often harvested from the wild as adults or juveniles.[37] These fishing activities significantly impact the populations of anemones and anemone fish by drastically reducing the densities of each in exploited areas.[37] Besides their collection from the wild for use in reef aquaria, sea anemones are also threatened by alterations to their environment. Those living in shallow-water coastal locations are affected directly by pollution and siltation, and indirectly by the effect these have on their photosynthetic symbionts and the prey on which they feed.[38]

In southwestern Spain and Sardinia, the

Fossil record

Most Actiniaria do not form hard parts that can be recognized as fossils, but a few fossils of sea anemones do exist;

Taxonomy

Sea anemones, order Actiniaria, are classified in the phylum Cnidaria, class Anthozoa, subclass Hexacorallia.[43] Rodriguez et al. proposed a new classification for the Actiniaria based on extensive DNA results.[44]

Suborders and superfamilies included in Actiniaria are:

- Suborder Anenthemonae

- Superfamily Edwardsioidea

- Superfamily Actinernoidea

- Superfamily

- Suborder Enthemonae

- Superfamily Actinostoloidea

- Superfamily Actinioidea

- Superfamily Metridioidea

Phylogeny

External relationships

†= extinct

| Anthozoa |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Internal relationships

The relationships of higher-level taxa in Carlgren's[46] classification are re-interpreted as follows:[44]

| Carlgren taxon | Phylogenetic result |

|---|---|

| Protantheae | Sister to Boloceroidaria |

| Ptychodacteae | Polyphyletic because its members are not recovered as sister taxa; clustered with members of former Endomyaria |

Endocoelantheae |

Sister to athenarian family Edwardsiidae; together these clades are re-classified as suborder Anenthemonae |

| Nynantheae | Polyphyletic because of the relationship between Edwardsiidae and Endocoelantheae and because members of Protantheae and Ptychodacteae are recovered as sister to its members |

| Boloceroidaria | Boloceroides mcmurrichi and Bunodeopsis nested among acontiate taxa; B. daphneae apart from other Actiniaria

|

| Athenaria | Polyphyletic: families formerly in this suborder distributed across tree as sister to former members of Endomyaria, Acontiaria, and Endocoelantheae |

| Thenaria | Boloceroidaria, Protantheae, Ptychodacteae, and most Athenaria nest within this group |

| Endomyaria | Paraphyletic: includes Pychodacteae and some Athenaria |

| Mesomyaria | Polyphyletic: one clade at base of Nynantheae, other lineages are associated with former members of Acontiaria |

| Acontiaria | Paraphyletic; includes several lineages formerly in Mesomyaria and Athenaria, plus Boloceroidaria and Protantheae |

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-8053-0009-3.

- PMID 22689365.

- National Marine Sanctuaries. January 12, 2006. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- PMID 22851928.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- McGraw-Hill. p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Carefoot, Tom. "Reproduction: sexual". Sea anemone. A Snail's Odyssey. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- .

- PMID 239758.

- PMID 21676808.

- ISBN 978-3-319-31305-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4757-9726-8.

- ^ Carefoot, Tom. "Reproduction: asexual". Sea anemone. A Snail's Odyssey. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- PMID 20686700.

- ^ "Heteractis magnifica: Life expectancy". Encyclopaedia of Life. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ISBN 978-81-7133-903-7.

- ^ a b Horton, Andy. "Sea anemones". British Marine Life Study Society. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- JSTOR 1535667.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-0-8078-9859-8.

- ^ Molodtsova, T. (2015). Cerianthidae. In: Fautin, Daphne G. (2011) Hexacorallians of the World. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species on 13 July 2017

- ^ a b "Sea anemone". Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2008.

- JSTOR 1540065.

- S2CID 23456096.

- ISBN 978-3-642-22505-5.

- ISBN 0-691-00481-1

- ^ Patzner, R.A. (5 July 2017). "Gobius incognitus". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Fretwell, K.; and B. Starzomski (2014). Painted greenling. Biodiversity of the Central Coast. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ^ ISBN 978-3931702748

- ^ Wittmann, K.J. (2008). Two new species of Heteromysini (Mysida, Mysidae) from the island of Madeira (N.E. Atlantic), with notes on sea anemone and hermit crab commensalisms in the genus Heteromysis S. I. Smith, 1873. Crustaceana, 81(3): 351–374.

- ^ a b Mercier, A.; and J. Hamel (2008). Nature and role of newly described symbiotic associations between a sea anemone and gastropods at bathyal depths in the NW Atlantic. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 358(1): 57–69.

- ^ a b Goodwill, R.H.; D.G. Fautin; J. Furey; and M. Daly (2009). A sea anemone symbiotic with gastropods of eight species in the Mariana Islands. Micronesica 41(1): 117–130.

- ^ a b Ates, R.M.L. (1997). Gastropod carrying actinians. In: J. C. den Hartog, eds, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Coelenterate Biology, 1995, pp. 11–20. National Naturhistorisch Museum, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- ^ Karplus, I; G.C. Fiedler; and P. Ramcharan (1998). The intraspecific fighting behavior of the Hawaiian Boxing Crab, Lybia edmondsoni – Fighting with dangerous weapons? Symbiosis 24: 287–302.

- ^ S2CID 25027153.

- ISBN 978-1-63188-108-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8139-0811-3.

- ^ B.H Ridzwan; M.A Kaswandi (1995). "Hidupan marin intertidal: sumber makanan penduduk daerah Semporna, Sabah". Malaysian Journal of Nutrition. 1 (2): 105–114.

- ^ Nurachmad Hadi; Sumadiyo. "Anemon Laut, Manfaat dan Bahayanya" (PDF). Oseana. XVII (4): 167–175.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. (1993). "Ediacaran-like fossils in Cambrian Burgess Shale–type faunas of North America". Palaeontology. 36 (31–0239): 593–635.

- ISSN 1175-5334.

- ^ PMID 24806477.

- PMID 24475157.

- ^ Carlgren O. (1949). A survey of the Ptychodactiaria, Corallimorpharia and Actiniaria. K Svenska VetenskapsAkad Handl 1: 1–121.

External links

- Order Actiniaria Archived 2008-07-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Actiniaria.com

- Photos of various species of Sea Anemones from the Indopacific

- Anemone Armies Battle to a Standoff

- Sea anemones look like sea flowers but they are animals of the Phylum Cnidaria

- Information about Ricordea Florida Sea anemones & pictures

- Photographic Database of Cambodian Sea Anemones

- Photos of Sea Anemones