Sea level rise

Between 1901 and 2018, average global

Rising seas affect every coastal and island population on Earth.

Local factors like

Societies can adapt to sea level rise in three ways. Managed retreat, accommodating coastal change, or protecting against sea level rise through hard-construction practices like seawalls[19] are hard approaches. There are also soft approaches such as dune rehabilitation and beach nourishment. Sometimes these adaptation strategies go hand in hand. At other times choices must be made among different strategies.[20] A managed retreat strategy is difficult if an area's population is increasing rapidly. This is a particularly acute problem for Africa. There, the population of low-lying coastal areas is likely to increase by around 100 million people within the next 40 years.[21] Poorer nations may also struggle to implement the same approaches to adapt to sea level rise as richer states. Sea level rise at some locations may be compounded by other environmental issues. One example is subsidence in sinking cities.[22] Coastal ecosystems typically adapt to rising sea levels by moving inland. Natural or artificial barriers may make that impossible.[23]

Observations

Between 1901 and 2018, the global mean sea level rose by about 20 cm (7.9 in).[4] More precise data gathered from satellite radar measurements found a rise of 7.5 cm (3.0 in) from 1993 to 2017 (average of 2.9 mm (0.11 in)/yr).[5] This accelerated to 4.62 mm (0.182 in)/yr for 2013–2022.[3]

Regional variations

Sea level rise is not uniform around the globe. Some land masses are moving up or down as a consequence of subsidence (land sinking or settling) or post-glacial rebound (land rising as melting ice reduces weight). Therefore, local relative sea level rise may be higher or lower than the global average. Changing ice masses also affect the distribution of sea water around the globe through gravity.[25][26]

When a glacier or ice sheet melts, it loses mass. This reduces its gravitational pull. In some places near current and former glaciers and ice sheets, this has caused water levels to drop. At the same time water levels will increase more than average further away from the ice sheet. Thus ice loss in

Many

Projections

There are two complementary ways to model sea level rise (SLR) and project the future. The first uses process-based modeling. This combines all relevant and well-understood physical processes in a global physical model. This approach calculates the contributions of ice sheets with an ice-sheet model and computes rising sea temperature and expansion with a general circulation model. The processes are imperfectly understood, but this approach has the advantage of predicting non-linearities and long delays in the response, which studies of the recent past will miss.

The other approach employs semi-empirical techniques. These use historical geological data to determine likely sea level responses to a warming world, and some basic physical modeling.[33] These semi-empirical sea level models rely on statistical techniques. They use relationships between observed past contributions to global mean sea level and temperature.[34] Scientists developed this type of modeling because most physical models in previous Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) literature assessments had underestimated the amount of sea level rise compared to 20th century observations.[26]

Projections for the 21st century

The lowest scenario in AR5, RCP2.6, would see greenhouse gas emissions low enough to meet the goal of limiting warming by 2100 to 2 °C (36 °F). It shows sea level rise in 2100 of about 44 cm (17 in) with a range of 28–61 cm (11–24 in). The "moderate" scenario, where CO2 emissions take a decade or two to peak and its atmospheric concentration does not plateau until 2070s is called RCP 4.5. Its likely range of sea level rise is 36–71 cm (14–28 in). The highest scenario in RCP8.5 pathway sea level would rise between 52 and 98 cm (20+1⁄2 and 38+1⁄2 in).[26][36] AR6 had equivalents for both scenarios, but it estimated larger sea level rise under both. In AR6, the SSP1-2.6 pathway results in a range of 32–62 cm (12+1⁄2–24+1⁄2 in) by 2100. The "moderate" SSP2-4.5 results in a 44–76 cm (17+1⁄2–30 in) range by 2100 and SSP5-8.5 led to 65–101 cm (25+1⁄2–40 in).[7]: 1302

Further, AR5 was criticized by multiple researchers for excluding detailed estimates the impact of "low-confidence" processes like marine ice sheet and marine ice cliff instability,[37][38][39] which can substantially accelerate ice loss to potentially add "tens of centimeters" to sea level rise within this century.[26] AR6 includes a version of SSP5-8.5 where these processes take place, and in that case, sea level rise of up to 1.6 m (5+1⁄3 ft) by 2100 could not be ruled out.[7]: 1302 The general increase of projections in AR6 was caused by the observed ice-sheet erosion in Greenland and Antarctica matching the upper-end range of the AR5 projections by 2020,[40][41] and the finding that AR5 projections were likely too slow next to an extrapolation of observed sea level rise trends, while the subsequent reports had improved in this regard.[42]

Notably, some scientists believe that ice sheet processes may accelerate sea level rise even at temperatures below the highest possible scenario, though not as much. For instance, a 2017 study from the

For comparison, a major scientific survey of 106 experts in 2020 found that even when accounting for instability processes they had estimated a median sea level rise of 45 cm (17+1⁄2 in) by 2100 for RCP2.6, with a 5%-95% range of 21–82 cm (8+1⁄2–32+1⁄2 in). For RCP8.5, the experts estimated a median of 93 cm (36+1⁄2 in) by 2100 and a 5%-95% range of 45–165 cm (17+1⁄2–65 in).

Post-2100 sea level rise

Even if the temperature stabilizes, significant sea-level rise (SLR) will continue for centuries,[49] consistent with paleo records of sea level rise.[26]: 1189 This is due to the high level of inertia in the carbon cycle and the climate system, owing to factors such as the slow diffusion of heat into the deep ocean, leading to a longer climate response time [50]. After 500 years, sea level rise from thermal expansion alone may have reached only half of its eventual level. Models suggest this may lie within ranges of 0.5–2 m (1+1⁄2–6+1⁄2 ft).[51] Additionally, tipping points of Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets are likely to play a larger role over such timescales.[52] Ice loss from Antarctica is likely to dominate very long-term SLR, especially if the warming exceeds 2 °C (3.6 °F). Continued carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel sources could cause additional tens of metres of sea level rise, over the next millennia. The available fossil fuel on Earth is enough to melt the entire Antarctic ice sheet, causing about 58 m (190 ft) of sea level rise.[53]

Based on research into multimillennial sea level rise [54], AR6 was able to create medium agreement estimates for the amount of sea level rise over the next 2,000 years, depending on the peak of global warming, which project that:

- At a warming peak of 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), global sea levels would rise 2–3 m (6+1⁄2–10 ft)

- At a warming peak of 2 °C (3.6 °F), sea levels would rise 2–6 m (6+1⁄2–19+1⁄2 ft)

- At a warming peak of 5 °C (9.0 °F), sea levels would rise 19–22 m (62+1⁄2–72 ft)[4]: SPM-21

Sea levels would continue to rise for several thousand years after the ceasing of emissions, due to the slow nature of climate response to heat. The same estimates on a timescale of 10,000 years project that:

- At a warming peak of 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), global sea levels would rise 6–7 m (19+1⁄2–23 ft)

- At a warming peak of 2 °C (3.6 °F), sea levels would rise 8–13 m (26–42+1⁄2 ft)

- At a warming peak of 5 °C (9.0 °F), sea levels would rise 28–37 m (92–121+1⁄2 ft)[7]: 1306

With better models and observational records, several studies have attempted to project SLR for the centuries immediately after 2100. This remains largely speculative. An April 2019 expert elicitation asked 22 experts about total sea level rise projections for the years 2200 and 2300 under its high, 5 °C warming scenario. It ended up with 90% confidence intervals of −10 cm (4 in) to 740 cm (24+1⁄2 ft) and −9 cm (3+1⁄2 in) to 970 cm (32 ft), respectively. Negative values represent the extremely low probability of very large increases in the ice sheet

By 2021, AR6 was also able to provide estimates for sea level rise in 2150 alongside the 2100 estimates for the first time. This showed that keeping warming at 1.5 °C under the SSP1-1.9 scenario would result in sea level rise in the 17-83% range of 37–86 cm (14+1⁄2–34 in). In the SSP1-2.6 pathway the range would be 46–99 cm (18–39 in), for SSP2-4.5 a 66–133 cm (26–52+1⁄2 in) range by 2100 and for SSP5-8.5 a rise of 98–188 cm (38+1⁄2–74 in). It stated that the "low-confidence, high impact" projected 0.63–1.60 m (2–5 ft) mean sea level rise by 2100, and that by 2150, the total sea level rise in his scenario would be in the range of 0.98–4.82 m (3–16 ft) by 2150.[7]: 1302 AR6 also provided lower-confidence estimates for year 2300 sea level rise under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 with various impact assumptions. In the best case scenario, under SSP1-2.6 with no ice sheet acceleration after 2100, the estimate was only 0.8–2.0 metres (2.6–6.6 ft). In the worst estimated scenario, SSP-8.5 with a marine ice cliff instability scenario, the projected range for total sea level rise was 9.5–16.2 metres (31–53 ft) by the year 2300. [7]: 1306

A 2018 paper estimated that sea level rise in 2300 would increase by a median of 20 cm (8 in) for every five years CO2 emissions increase before peaking. It shows a 5% likelihood of a 1 m (3+1⁄2 ft) increase due to the same. The same estimate found that if the temperature stabilized below 2 °C (3.6 °F), 2300 sea level rise would still exceed 1.5 m (5 ft). Early

Measurements

Variations in the amount of water in the oceans, changes in its volume, or varying land elevation compared to the sea surface can drive sea level changes. Over a consistent time period, assessments can attribute contributions to sea level rise and provide early indications of change in trajectory. This helps to inform adaptation plans.

Satellites

Since the launch of TOPEX/Poseidon in 1992, an overlapping series of altimetric satellites has been continuously recording the sea level and its changes.[58] These satellites can measure the hills and valleys in the sea caused by currents and detect trends in their height. To measure the distance to the sea surface, the satellites send a microwave pulse towards Earth and record the time it takes to return after reflecting off the ocean's surface. Microwave radiometers correct the additional delay caused by water vapor in the atmosphere. Combining these data with the location of the spacecraft determines the sea-surface height to within a few centimetres.[59] These satellite measurements have estimated rates of sea level rise for 1993–2017 at 3.0 ± 0.4 millimetres (1⁄8 ± 1⁄64 in) per year.[60]

Satellites are useful for measuring regional variations in sea level. An example is the substantial rise between 1993 and 2012 in the western tropical Pacific. This sharp rise has been linked to increasing

Tide gauges

The global network of tide gauges is the other important source of sea-level observations. Compared to the satellite record, this record has major spatial gaps but covers a much longer period.[64] Coverage of tide gauges started mainly in the Northern Hemisphere. Data for the Southern Hemisphere remained scarce up to the 1970s.[64] The longest running sea-level measurements, NAP or Amsterdam Ordnance Datum were established in 1675, in Amsterdam.[65] Record collection is also extensive in Australia. They including measurements by an amateur meteorologist beginning in 1837. They also include measurements taken from a sea-level benchmark struck on a small cliff on the Isle of the Dead near the Port Arthur convict settlement in 1841.[66]

Together with satellite data for the period after 1992, this network established that global mean sea level rose 19.5 cm (7.7 in) between 1870 and 2004 at an average rate of about 1.44 mm/yr. (For the 20th century the average is 1.7 mm/yr.)

Regional differences are also visible in the tide gauge data. Some are caused by local sea level differences. Others are due to vertical land movements. In Europe, only some land areas are rising while the others are sinking. Since 1970, most tidal stations have measured higher seas. However sea levels along the northern Baltic Sea have dropped due to post-glacial rebound.[70]

Past sea level rise

Since the Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 years ago, sea level has risen by more than 125 metres (410 ft). Rates vary from less than 1 mm/year during the pre-industrial era to 40+ mm/year when major ice sheets over Canada and Eurasia melted. Meltwater pulses are periods of fast sea level rise caused by the rapid disintegration of these ice sheets. The rate of sea level rise started to slow down about 8,200 years before today. Sea level was almost constant for the last 2,500 years. The recent trend of rising sea level started at the end of the 19th or beginning of the 20th century.[73]

Causes

The three main reasons warming causes global sea level to rise are the expansion of oceans due to heating, water inflow from melting ice sheets and water inflow from glaciers. Glacier retreat and ocean expansion have dominated sea level rise since the start of the 20th century.[33] Some of the losses from glaciers are offset when precipitation falls as snow, accumulates and over time forms glacial ice. If precipitation, surface processes and ice loss at the edge balance each other, sea level remains the same. Because of this precipitation began as water vapor evaporated from the ocean surface, effects of climate change on the water cycle can even increase ice build-up. However, this effect is not enough to fully offset ice losses, and sea level rise continues to accelerate.[21][75][76][77]

The contributions of the two large ice sheets, in Greenland and Antarctica, are likely to increase in the 21st century.[33] They store most of the land ice (~99.5%) and have a sea-level equivalent (SLE) of 7.4 m (24 ft 3 in) for Greenland and 58.3 m (191 ft 3 in) for Antarctica.[5] Thus, melting of all the ice on Earth would result in about 70 m (229 ft 8 in) of sea level rise,[78] although this would require at least 10,000 years and up to 10 °C (18 °F) of global warming.[79][80]

Ocean heating

The oceans store more than 90% of the extra heat added to the climate system by

When the ocean gains heat, the water expands and sea level rises. Warmer water and water under great pressure (due to depth) expand more than cooler water and water under less pressure.[26]: 1161 Consequently, cold Arctic Ocean water will expand less than warm tropical water. Different climate models present slightly different patterns of ocean heating. So their projections do not agree fully on how much ocean heating contributes to sea level rise.[85]

Antarctic ice loss

The large volume of ice on the Antarctic continent stores around 60% of the world's fresh water. Excluding groundwater this is 90%.[86] Antarctica is experiencing ice loss from coastal glaciers in the West Antarctica and some glaciers of East Antarctica. However it is gaining mass from the increased snow build-up inland, particularly in the East. This leads to contradicting trends.[77][87] There are different satellite methods for measuring ice mass and change. Combining them helps to reconcile the differences.[88] However, there can still be variations between the studies. In 2018, a systematic review estimated average annual ice loss of 43 billion tons (Gt) across the entire continent between 1992 and 2002. This tripled to an annual average of 220 Gt from 2012 to 2017.[75][89] However, a 2021 analysis of data from four different research satellite systems (Envisat, European Remote-Sensing Satellite, GRACE and GRACE-FO and ICESat) indicated annual mass loss of only about 12 Gt from 2012 to 2016. This was due to greater ice gain in East Antarctica than estimated earlier.[77]

In the future, it is known that West Antarctica at least will continue to lose mass, and the likely future losses of sea ice and ice shelves, which block warmer currents from direct contact with the ice sheet, can accelerate declines even in East Antarctica.[90][91] Altogether, Antarctica is the source of the largest uncertainty for future sea level projections.[92] In 2019, the SROCC assessed several studies attempting to estimate 2300 sea level rise caused by ice loss in Antarctica alone, arriving at projected estimates of 0.07–0.37 metres (0.23–1.21 ft) for the low emission RCP2.6 scenario, and 0.60–2.89 metres (2.0–9.5 ft) in the high emission RCP8.5 scenario.[7]: 1272 However, the report notes the wide range of estimates, and gives low confidence in the projection, saying that it retains "deep uncertainty" in their ability to estimate the whole of long term damage to Antarctic ice, especially in scenarios of very high emissions.

East Antarctica

The world's largest potential source of sea level rise is the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS). It is 2.2 km thick on average and holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by 53.3 m (174 ft 10 in)[93] Its great thickness and high elevation make it more stable than the other ice sheets.[94] As of the early 2020s, most studies show that it is still gaining mass.[95][75][77][87] Some analyses have suggested it began to lose mass in the 2000s.[96][76][91] However they over-extrapolated some observed losses on to the poorly observed areas. A more complete observational record shows continued mass gain.[77]

In spite of the net mass gain, some East Antarctica glaciers have lost ice in recent decades due to

On the other hand, the whole EAIS would not definitely collapse until global warming reaches 7.5 °C (13.5 °F), with a range between 5 °C (9.0 °F) and 10 °C (18 °F). It would take at least 10,000 years to disappear.[79][80] Some scientists have estimated that warming would have to reach at least 6 °C (11 °F) to melt two thirds of its volume.[103]

West Antarctica

East Antarctica contains the largest potential source of sea level rise. However the

Scientists estimated in 2021 that the median increase in sea level rise from Antarctica by 2100 is ~11 cm (5 in). There is no difference between scenarios, because the increased warming would

The contribution of these glaciers to global sea levels has already accelerated since the beginning of the 21st century. The Thwaites Glacier now accounts for 4% of global sea level rise.

Other hard-to-model processes include hydrofracturing, where meltwater collects atop the ice sheet, pools into fractures and forces them open.[37] and changes in the ocean circulation at a smaller scale.[114][115][116] A combination of these processes could cause the WAIS to contribute up to 41 cm (16 in) by 2100 under the low-emission scenario and up to 57 cm (22 in) under the highest-emission one.[7]

The melting of all the

The only way to stop ice loss from West Antarctica once triggered is by lowering the global temperature to 1 °C (1.8 °F) below the preindustrial level. This would be 2 °C (3.6 °F) below the temperature of 2020.[103] Other researchers suggested that a climate engineering intervention to stabilize the ice sheet's glaciers may delay its loss by centuries and give more time to adapt. However this is an uncertain proposal, and would end up as one of the most expensive projects ever attempted.[126][127]

Isostatic rebound

2021 research indicates that

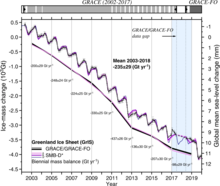

Greenland ice sheet loss

Most ice on Greenland is in the

In 2021,

Greenland's peripheral glaciers and ice caps crossed an irreversible tipping point around 1997. Sea level rise from their loss is now unstoppable.[134][135][136] However the temperature changes in future, the warming of 2000–2019 had already damaged the ice sheet enough for it to eventually lose ~3.3% of its volume. This is leading to 27 cm (10+1⁄2 in) of future sea level rise.[137] At a certain level of global warming, the Greenland ice sheet will almost completely melt. Ice cores show this happened at least once during the last million years, when the temperatures have at most been 2.5 °C (4.5 °F) warmer than the preindustrial.[138][139]

2012 research suggested that the tipping point of the ice sheet was between 0.8 °C (1.4 °F) and 3.2 °C (5.8 °F).[140] 2023 modelling has narrowed the tipping threshold to a 1.7 °C (3.1 °F)-2.3 °C (4.1 °F) range. If temperatures reach or exceed that level, reducing the global temperature to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above pre-industrial levels or lower would prevent the loss of the entire ice sheet. One way to do this in theory would be large-scale carbon dioxide removal. But it would also cause greater losses and sea level rise from Greenland than if the threshold was not breached in the first place.[141] Otherwise, the ice sheet would take between 10,000 and 15,000 years to disintegrate entirely once the tipping point had been crossed. The most likely estimate is 10,000 years.[79][80] If climate change continues along its worst trajectory and temperatures continue to rise quickly over multiple centuries, it would only take 1,000 years.[142]

Mountain glacier loss

There are roughly 200,000 glaciers on Earth, which are spread out across all continents.[144] Less than 1% of glacier ice is in mountain glaciers, compared to 99% in Greenland and Antarctica. However, this small size also makes mountain glaciers more vulnerable to melting than the larger ice sheets. This means they have had a disproportionate contribution to historical sea level rise and are set to contribute a smaller, but still significant fraction of sea level rise in the 21st century.[145] Observational and modelling studies of mass loss from glaciers and ice caps show they contribute 0.2-0.4 mm per year to sea level rise, averaged over the 20th century.[146] The contribution for the 2012–2016 period was nearly as large as that of Greenland. It was 0.63 mm of sea level rise per year, equivalent to 34% of sea level rise from land ice sources.[131] Glaciers contributed around 40% to sea level rise during the 20th century, with estimates for the 21st century of around 30%.[5]

In 2023, a

Sea ice loss

Sea ice loss contributes very slightly to global sea level rise. If the melt water from ice floating in the sea was exactly the same as sea water then, according to

Changes to land water storage

Human activity impacts how much water is stored on land. Dams retain large quantities of water, which is stored on land rather than flowing into the sea, though the total quantity stored will vary from time to time. On the other hand, humans extract water from lakes, wetlands and underground reservoirs for food production. This often causes subsidence. Furthermore, the hydrological cycle is influenced by climate change and deforestation. This can increase or reduce contributions to sea level rise. In the 20th century, these processes roughly balanced, but dam building has slowed down and is expected to stay low for the 21st century.[149][26]: 1155

Water redistribution caused by irrigation from 1993 to 2010 caused a drift of Earth's rotational pole by 78.48 centimetres (30.90 in). This caused groundwater depletion equivalent to a global sea level rise of 6.24 millimetres (0.246 in).[150]

Impacts

Sea-level rise has many impacts. They include higher and more frequent high-tide and

Changes in emissions are likely to have only a small effect on the extent of sea level rise by 2050.[6] So projected sea level rise could put tens of millions of people at risk by then. Scientists estimate that 2050 levels of sea level rise would result in about 150 million people under the water line during high tide. About 300 million would be in places flooded every year. This projection is based on the distribution of population in 2010. It does not take into account the effects of population growth and human migration. These figures are 40 million and 50 million more respectively than the numbers at risk in 2010.[13][153] By 2100, there would be another 40 million people under the water line during high tide if sea level rise remains low. This figure would be 80 million for a high estimate of median sea level rise.[13] Ice sheet processes under the highest emission scenario would result in sea level rise of well over one metre (3+1⁄4 ft) by 2100. This could be as much as over two metres (6+1⁄2 ft),[16][4]: TS-45 This could result in as many as 520 million additional people ending up under the water line during high tide and 640 million in places flooded every year, compared to the 2010 population distribution.[13]

Over the longer term, coastal areas are particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels. They are also vulnerable to changes in the frequency and intensity of storms, increased precipitation, and rising ocean temperatures. Ten percent of the world's population live in coastal areas that are less than 10 metres (33 ft) above sea level. Two thirds of the world's cities with over five million people are located in these low-lying coastal areas.[156] About 600 million people live directly on the coast around the world.[157] Cities such as Miami, Rio de Janeiro, Osaka and Shanghai will be especially vulnerable later in the century under warming of 3 °C (5.4 °F). This is close to the current trajectory.[12][36] LiDAR-based research had established in 2021 that 267 million people worldwide lived on land less than 2 m (6+1⁄2 ft) above sea level. With a 1 m (3+1⁄2 ft) sea level rise and zero population growth, that could increase to 410 million people.[158][159]

Potential disruption of sea trade and migrations could impact people living further inland. United Nations Secretary-General

Ecosystems

Flooding and soil/water salinization threaten the habitats of

Some ecosystems can move inland with the high-water mark. But natural or artificial barriers prevent many from migrating. This coastal narrowing is sometimes called 'coastal squeeze' when it involves human-made barriers. It could result in the loss of habitats such as

Corals are important for bird and fish life. They need to grow vertically to remain close to the sea surface in order to get enough energy from sunlight. The corals have so far been able to keep up the vertical growth with the rising seas, but might not be able to do so in the future.[179]

Regional impacts

Africa

In Africa, future population growth amplifies risks from sea level rise. Some 54.2 million people lived in the highly exposed low elevation coastal zones (LECZ) around 2000. This number will effectively double to around 110 million people by 2030. By 2060 it will be around 185 to 230 million people, depending on the extent of population growth. The average regional sea level rise will be around 21 cm by 2060. At that point climate change scenarios will make little difference. But local geography and population trends interact to increase the exposure to hazards like 100-year floods in a complex way.[21]

| Country | 2000 | 2030 | 2060 | Growth 2000–2060[T1 2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | 7.4 | 13.8 | 20.7 | 0.28 |

| Nigeria | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.84 |

| Senegal | 0.4 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 0.76 |

| Benin | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.12 |

| Tanzania | 0.2 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 2.3 |

| Somalia | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 1.7 |

Cote d'Ivoire |

0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.65 |

| Mozambique | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 0.36 |

In the near term, some of the largest displacement is projected to occur in the

In the longer term,

Asia

As of 2022, some 63 million people in

Modeling results predict that Asia will suffer direct economic damages of US$167.6 billion at 0.47 meters of sea level rise. This rises to US$272.3 billion at 1.12 meters and US$338.1 billion at 1.75 meters. There is an additional indirect impact of US$8.5, 24 or 15 billion from population displacement at those levels. China, India, the

Out of the 20 coastal cities expected to see the highest flood losses by 2050, 13 are in Asia. For nine of these, subsidence would compound sea level rise. These are Bangkok, Guangzhou, Ho Chi Minh City, Jakarta, Kolkata, Nagoya, Tianjin, Xiamen and Zhanjiang. By 2050, Guangzhou would see 0.2 meters of sea level rise and estimated annual economic losses of US$254 million – the highest in the world. One estimate calculates that in the absence of adaptation, cumulative economic losses caused by sea level rise in Guangzhou under RCP8.5 would reach about US$331 billion by 2050, US$660 billion by 2070 and US$1.4 trillion by 2100. The impact of high-end ice sheet instability would increase these figures to about US$420 billion, US$840 billion and US$1.8 trillion respectively.[17]

In

Sea level rise in Bangladesh may force the relocation of up to one third of power plants by 2030. A similar proportion would have to deal with increased salinity of their cooling water. Recent search indicates that by 2050 sea-level rise will displace 0.9-2.1 million people. This would require the creation of about 594,000 new jobs and 197,000 housing units in the areas receiving the displaced persons. It would also be necessary to supply an additional 783 billion calories worth of food.[17] Another paper in 2021 estimated that sea-level rise would displace 816,000 people by 2050. This would increase to 1.3 million when indirect effects are taken into account.[182] Both studies assume that most displaced people would travel to the other areas of Bangladesh. They try to estimate population changes in different places.

| District | Net flux (Davis et al., 2018) | Net flux (De Lellis et al., 2021) | Rank (Davis et al., 2018)[T2 1] | Rank (De Lellis et al., 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhaka | 207,373 | −34, 060 | 1 | 11 |

| Narayanganj | −95,003 | −126,694 | 2 | 1 |

| Shariatpur | −80,916 | −124,444 | 3 | 3 |

| Barisal | −80,669 | −64,252 | 4 | 6 |

| Munshiganj | −77,916 | −124,598 | 5 | 2 |

| Madaripur | 61,791 | −937 | 6 | 60 |

| Chandpur | −37,711 | −70,998 | 7 | 4 |

Jhalakati |

35,546 | 9,198 | 8 | 36 |

| Satkhira | −32,287 | −19,603 | 9 | 23 |

| Khulna | −28,148 | −9,982 | 10 | 33 |

| Cox's Bazar | −25,680 | −16,366 | 11 | 24 |

| Bagherat | 24,860 | 12,263 | 12 | 28 |

- ^ Refers to the magnitude of population change relative to the other districts.

In an attempt to address these challenges, the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 was launched in 2018.[183][184] As of 2020, it was falling short of most of its initial targets.[185] The authorities are monitoring progress.[186]

In 2019, the president of Indonesia,

Australasia

In

Central and South America

By 2100, coastal flooding and erosion will affect at least 3-4 million people in

Europe

Many sandy coastlines in Europe are vulnerable to erosion due to sea level rise. In Spain, Costa del Maresme is likely to retreat by 16 meters by 2050 relative to 2010. This could amount to 52 meters by 2100 under RCP8.5[194] Other vulnerable coastlines include the Tyrrhenian Sea coast of Italy's Calabria region,[195] the Barra-Vagueira coast in Portugal[196] and Nørlev Strand in Denmark.[197]

In France, it was estimated that 8,000-10,000 people would be forced to migrate away from the coasts by 2080.

The

North America

As of 2017, around 95 million Americans lived on the coast. The figures for

In future, the northern

Island nations

Small island states are nations with populations on

Adaptation to sea level rise is costly for small island nations as a large portion of their population lives in areas that are at risk.

Adaptation

Cutting greenhouse gas emissions can slow and stabilize the rate of sea level rise after 2050. This would greatly reduce its costs and damages, but cannot stop it outright. So climate change adaptation to sea level rise is inevitable.[232]: 3–127 The simplest approach is to stop development in vulnerable areas and ultimately move people and infrastructure away from them. Such retreat from sea level rise often results in the loss of livelihoods. The displacement of newly impoverished people could burden their new homes and accelerate social tensions.[233]

It is possible to avoid or at least delay the retreat from sea level rise with enhanced protections. These include

To be successful, adaptation must anticipate sea level rise well ahead of time. As of 2023, the global state of adaptation planning is mixed. A survey of 253 planners from 49 countries found that 98% are aware of sea level rise projections, but 26% have not yet formally integrated them into their policy documents. Only around a third of respondents from Asian and South American countries have done so. This compares with 50% in Africa, and over 75% in Europe, Australasia and North America. Some 56% of all surveyed planners have plans which account for 2050 and 2100 sea level rise. But 53% use only a single projection rather than a range of two or three projections. Just 14% use four projections, including the one for "extreme" or "high-end" sea level rise.

See also

- Sea level drop

- Climate emergency declaration

- Climate engineering

- Coastal development hazards

- Effects of climate change on oceans

- Effects of climate change on small island countries

- Hydrosphere

- Islands First

- List of countries by average elevation

References

- ^ "Climate Change Indicators: Sea Level / Figure 1. Absolute Sea Level Change". EPA.gov. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). July 2022. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023.

Data sources: CSIRO, 2017. NOAA, 2022.

- ^ IPCC, 2019: Summary for Policymakers. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N. M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, New York, US. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.001.

- ^ a b c "WMO annual report highlights continuous advance of climate change". World Meteorological Organization. 21 April 2023.

Press Release Number: 21042023

- ^ a b c d e f IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001.

- ^ .

This corresponds to a mean sea-level rise of about 7.5 cm over the whole altimetry period. More importantly, the GMSL curve shows a net acceleration, estimated to be at 0.08mm/yr2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-309-15176-4.

Box SYN-1: Sustained warming could lead to severe impacts

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fox-Kemper, B.; Hewitt, Helene T.; Xiao, C.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, G.; Drijfhout, S. S.; Edwards, T. L.; Golledge, N. R.; Hemer, M.; Kopp, R. E.; Krinner, G.; Mix, A. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S. L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (eds.). "Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change" (PDF). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, US.

- PMID 34149864.

- ISBN 978-0-521-88009-1. Archived from the originalon 20 June 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ ISBN 0521-80767-0. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Sea level to increase risk of deadly tsunamis". United Press International. 2018.

- ^ a b Holder, Josh; Kommenda, Niko; Watts, Jonathan (3 November 2017). "The three-degree world: cities that will be drowned by global warming". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ PMID 31664024.

- PMID 23883609.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (27 June 2012). "Sea Levels Rising Fast on U.S. East Coast". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shaw, R., Y. Luo, T. S. Cheong, S. Abdul Halim, S. Chaturvedi, M. Hashizume, G. E. Insarov, Y. Ishikawa, M. Jafari, A. Kitoh, J. Pulhin, C. Singh, K. Vasant, and Z. Zhang, 2022: Chapter 10: Asia. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US, pp. 1457–1579 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.012.

- ^ Mycoo, M., M. Wairiu, D. Campbell, V. Duvat, Y. Golbuu, S. Maharaj, J. Nalau, P. Nunn, J. Pinnegar, and O. Warrick, 2022: Chapter 15: Small islands. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US, pp. 2043–2121 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.017.

- ^ "IPCC's New Estimates for Increased Sea-Level Rise". Yale University Press. 2013.

- ^ JSTOR 26269087.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Trisos, C. H., I. O. Adelekan, E. Totin, A. Ayanlade, J. Efitre, A. Gemeda, K. Kalaba, C. Lennard, C. Masao, Y. Mgaya, G. Ngaruiya, D. Olago, N. P. Simpson, and S. Zakieldeen 2022: Chapter 9: Africa. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US, pp. 2043–2121 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.011.

- S2CID 8238425.

- ^ a b "Sea level rise poses a major threat to coastal ecosystems and the biota they support". birdlife.org. Birdlife International. 2015.

- ^ 27-year Sea Level Rise – TOPEX/JASON NASA Visualization Studio, 5 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- S2CID 2242594.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Church, J. A.; Clark, P. U. (2013). "Sea Level Change". In Stocker, T. F.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

- S2CID 131866367.

- ^ "Why the U.S. East Coast could be a major 'hotspot' for rising seas". The Washington Post. 2016.

- ^ Jianjun Yin & Stephen Griffies (March 25, 2015). "Extreme sea level rise event linked to AMOC downturn". CLIVAR.

- S2CID 12295500.

- ^ OCLC 768078077.

- S2CID 199393735.

- ^ PMID 26903648.

- ^ Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, Daniela; Taylor, Michael (2018). "Impacts of 1.5 °C of Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems" (PDF). Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. In Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ "January 2017 analysis from NOAA: Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States" (PDF).

- ^ a b "The CAT Thermometer". Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ PMID 30013142.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 9410444.

- ^ "Ice sheet melt on track with 'worst-case climate scenario'". www.esa.int. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ S2CID 221381924. Archived from the originalon 2 September 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- S2CID 234353584.

- ^ Chris Mooney (October 26, 2017). "New science suggests the ocean could rise more – and faster – than we thought". The Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois.

- .

- ^ "James Hansen's controversial sea level rise paper has now been published online". The Washington Post. 2015.

There is no doubt that the sea level rise, within the IPCC, is a very conservative number," says Greg Holland, a climate and hurricane researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, who has also reviewed the Hansen study. "So the truth lies somewhere between IPCC and Jim.

- ^ S2CID 218541055.

- ^ PMID 31110015.

- ^ a b "Anticipating Future Sea Levels". EarthObservatory.NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2021. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-309-14588-6. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- ISSN 0036-8075. Archived from the original(PDF) on March 27, 2021 – via NASA.

- PMID 19179281.

- S2CID 91886763.

- PMID 26601273.

- ISSN 1758-6798. Archived from the originalon July 11, 2020 – via Oregon State University.

- PMID 29463787.

- ^ "2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- S2CID 131866367.

- ^ "Ocean Surface Topography from Space". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- ^ "Jason-3 Satellite – Mission". www.nesdis.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- PMID 29440401.

- S2CID 128907116.

- .

- ^ Lindsey, Rebecca (2019) Climate Change: Global Sea Level NOAA Climate, 19 November 2019.

- ^ a b Rhein, Monika; Rintoul, Stephan (2013). "Observations: Ocean" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WGI. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 285. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ^ "Other Long Records not in the PSMSL Data Set". PSMSL. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- S2CID 55384210.

- S2CID 129887186.

- ^ "Historical sea level changes: Last decades". www.cmar.csiro.au. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ^ Neil, White. "Historical Sea Level Changes". CSIRO. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Global and European sea level rise". European Environment Agency. 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Scientists discover evidence for past high-level sea rise". phys.org. 2019-08-30. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- ^ "Present CO2 levels caused 20-metre-sea-level rise in the past". Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research.

- PMID 25313072.

- S2CID 234098716. Fig. 4.

- ^ S2CID 49188002.

- ^ PMID 30642972.

- ^ .

Although their methods of interpolation or extrapolation for areas with unobserved output velocities have an insufficient description for the evaluation of associated errors, such errors in previous results (Rignot and others, 2008) caused large overestimates of the mass losses as detailed in Zwally and Giovinetto (Zwally and Giovinetto, 2011).

- ^ "How would sea level change if all glaciers melted?". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ S2CID 252161375.

- ^ a b c d e f Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Top 700 meters: Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann (6 September 2023). "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. ● Top 2000 meters: "Ocean Warming / Latest Measurement: December 2022 / 345 (± 2) zettajoules since 1955". NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023.

- .

- .

- ^ Upton, John (2016-01-19). "Deep Ocean Waters Are Trapping Vast Stores of Heat". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- S2CID 19120823.

- ^ "Antarctic Factsheet". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ a b NASA (7 July 2023). "Antarctic Ice Mass Loss 2002-2023".

- S2CID 32653236.

- ^ Scott K. Johnson (2018-06-13). "Latest estimate shows how much Antarctic ice has fallen into the sea". Ars Technica.

- ^ .

- ^ a b "Antarctica ice melt has accelerated by 280% in the last 4 decades". CNN. 14 January 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

Melting is taking place in the most vulnerable parts of Antarctica ... parts that hold the potential for multiple metres of sea level rise in the coming century or two

- S2CID 233871029. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Alt URL https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/173870/

- .

- S2CID 222179485.

- S2CID 4414976.

- S2CID 130927366.

- ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (2020-03-23). "Climate change: Earth's deepest ice canyon vulnerable to melting". BBC.

- PMID 29109976.

- S2CID 55567382.

- doi:10.1038/ngeo2388.

- ^ PMID 33931453.

- ^ S2CID 221885420.

- S2CID 131723421.

- S2CID 784105.

- ^ Science Magazine. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

Because Thwaites sits below sea level on ground that dips away from the coast, the warm water is likely to melt its way inland, beneath the glacier itself, freeing its underbelly from bedrock. A collapse of the entire glacier, which some researchers think is only centuries away, would raise global sea level by 65 centimeters.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (December 13, 2021). "Thwaites: Antarctic glacier heading for dramatic change". BBC News. London. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Threat from Thwaites: The Retreat of Antarctica's Riskiest Glacier" (Press release). Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES). University of Colorado Boulder. 2021-12-13. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2021-12-14.

- ^ "After Decades of Losing Ice, Antarctica Is Now Hemorrhaging It". The Atlantic. 2018.

- ^ "Marine ice sheet instability". AntarcticGlaciers.org. 2014.

- ^ Kaplan, Sarah (December 13, 2021). "Crucial Antarctic ice shelf could fail within five years, scientists say". The Washington Post. Washington DC. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- PMID 31285345.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (June 17, 2021). "Collapse may not always be inevitable for marine ice cliffs". ScienceNews. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- S2CID 59606358.

- S2CID 219487981.

- ^ S2CID 264476246.

- (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- PMID 26838462.

- S2CID 11083712.

- ^ Voosen, Paul (2018-12-18). "Discovery of recent Antarctic ice sheet collapse raises fears of a new global flood". Science. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- PMID 32047039.

- ^ Carlson, Anders E; Walczak, Maureen H; Beard, Brian L; Laffin, Matthew K; Stoner, Joseph S; Hatfield, Robert G (10 December 2018). Absence of the West Antarctic ice sheet during the last interglaciation. American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting.

- S2CID 266436146.

- ^ AHMED, Issam. "Antarctic octopus DNA reveals ice sheet collapse closer than thought". phys.org. Retrieved 2023-12-23.

- ^ Poynting, Mark (24 October 2023). "Sea-level rise: West Antarctic ice shelf melt 'unavoidable'". BBC. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- PMID 37007716.

- PMID 37091546.

- ^ "NASA Earth Observatory - Newsroom". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 18 January 2019.

- S2CID 4468824.

- S2CID 219146922.

- ^ .

- ^ "Greenland ice loss is at 'worse-case scenario' levels, study finds". UCI News. 2019-12-19. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- S2CID 221200001..

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - PMID 28361871.

- ^ "Warming Greenland ice sheet passes point of no return". Ohio State University. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ISSN 2662-4435..

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - S2CID 251912711.

- PMID 31871153.

- PMID 33723012.

- .

- PMID 37853149.

- PMID 31223652.

- S2CID 255441012.

- S2CID 3256381.

- doi:10.1038/ngeo1052.

- doi:10.7265/N52N506F.

- S2CID 255441012.

- .

- PMID 32269399.

- S2CID 259275991.

- ^ Sweet, William V.; Dusek, Greg; Obeysekera, Jayantha; Marra, John J. (February 2018). "Patterns and Projections of High Tide Flooding Along the U.S. Coastline Using a Common Impact Threshold" (PDF). tidesandcurrents.NOAA.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 October 2022.

Fig. 2b

- .

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (October 30, 2019). "300 Million People Worldwide Could Suffer Yearly Flooding by 2050". Ecowatch. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ File:Projections of global mean sea level rise by Parris et al. (2012).png

- ^ "How much will sea levels rise in the 21st Century?". Skeptical Science.

- S2CID 154588933.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (13 February 2020). "A Crisis Right Now: San Francisco and Manila Face Rising Seas". The New York Times. Photographer: Chang W. Lee. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Storer, Rhi (2021-06-29). "Up to 410 million people at risk from sea level rises – study". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- PMID 34188026.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (14 February 2023). "Rising seas threaten 'mass exodus on a biblical scale', UN chief warns". The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- S2CID 239647501.

- ^ "Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities — Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate". Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ a b Michaelson, Ruth (25 August 2018). "Houses claimed by the canal: life on Egypt's climate change frontline". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ a b Nagothu, Udaya Sekhar (2017-01-18). "Food security threatened by sea-level rise". Nibio. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ "Sea Level Rise". National Geographic. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Ghost forests are eerie evidence of rising seas". Grist.org. 18 September 2016. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- ^ "How Rising Seas Are Killing Southern U.S. Woodlands - Yale E360". e360.yale.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- PMID 37081050.

- ^ Smith, Lauren (2016-06-15). "Extinct: Bramble Cay melomys". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ^ Hannam, Peter (2019-02-19). "'Our little brown rat': first climate change-caused mammal extinction". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- .

- ^ "Mangroves - Northland Regional Council". www.nrc.govt.nz.

- S2CID 6929383.

- PMID 24251960.

- JSTOR 25737579.

- .

- ^ Spalding, M.; McIvor, A.; Tonneijck, F.H.; Tol, S.; van Eijk, P. (2014). "Mangroves for coastal defence. Guidelines for coastal managers & policy makers" (PDF). Wetlands International and The Nature Conservancy.

- S2CID 128615335.

- ^ Wong, Poh Poh; Losado, I.J.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Hinkel, Jochen (2014). "Coastal Systems and Low-Lying Areas" (PDF). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. New York: Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- S2CID 150179939.

- ^ "Potential Impacts of Sea-Level Rise on Populations and Agriculture". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 2020-04-18. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

- ^ S2CID 233626963.

- ^ "Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 | Dutch Water Sector". www.dutchwatersector.com (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-12-11.

- ^ "Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP) 2100" (PDF).

- ^ "Delta Plan falls behind targets at the onset". The Business Standard. September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 Formulation project".

- ^ Englander, John (3 May 2019). "As seas rise, Indonesia is moving its capital city. Other cities should take note". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- S2CID 129557182.

- ^ Englander, John (May 3, 2019). "As seas rise, Indonesia is moving its capital city. Other cities should take note". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (May 3, 2019). "Indonesia Will Move its Capital from Fast-Sinking Jakarta". Ecowatch. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ISSN 2199-899X.

- ^ Lawrence, J., B. Mackey, F. Chiew, M.J. Costello, K. Hennessy, N. Lansbury, U.B. Nidumolu, G. Pecl, L. Rickards, N. Tapper, A. Woodward, and A. Wreford, 2022: Chapter 11: Australasia. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 1581–1688, |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.013

- ^ Castellanos, E., M.F. Lemos, L. Astigarraga, N. Chacón, N. Cuvi, C. Huggel, L. Miranda, M. Moncassim Vale, J.P. Ometto, P.L. Peri, J.C. Postigo, L. Ramajo, L. Roco, and M. Rusticucci, 2022: Chapter 12: Central and South America. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 1689–1816 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.014

- S2CID 135328414.

- S2CID 134889581.

- S2CID 222318289.

- S2CID 231794192.

- PMID 36914726.

- ^ Calma, Justine (November 14, 2019). "Venice's historic flooding blamed on human failure and climate change". The Verge. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Shepherd, Marshall (16 November 2019). "Venice Flooding Reveals A Real Hoax About Climate Change - Framing It As "Either/Or"". Forbes. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ S2CID 246354121.

- S2CID 203120550.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ^ "Dutch draw up drastic measures to defend coast against rising seas". The New York Times. 3 September 2008.

- ^ "Rising Sea Levels Threaten Netherlands". National Post. Toronto. Agence France-Presse. September 4, 2008. p. AL12. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ "Florida Coastal Flooding Maps: Residents Deny Predicted Risks to Their Property". EcoWatch. 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

- S2CID 19624347.

- ^ "High Tide Flooding". NOAA. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ "Climate Change, Sea Level Rise Spurring Beach Erosion". Climate Central. 2012.

- PMID 32411525.

- PMID 32591535.

- ^ a b c Hicke, J.A., S. Lucatello, L.D., Mortsch, J. Dawson, M. Domínguez Aguilar, C.A.F. Enquist, E.A. Gilmore, D.S. Gutzler, S. Harper, K. Holsman, E.B. Jewett, T.A. Kohler, and KA. Miller, 2022: Chapter 14: North America. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 1929–2042

- S2CID 234783225.

- ^ Seabrook, Victoria (19 May 2021). "Climate change to blame for $8 billion of Hurricane Sandy losses, study finds". Nature Communications. Sky News. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ "U.S Coastline to See Up to a Foot of Sea Level by 2050". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 15 February 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- NOAA. 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ Gornitz, Vivien (2002). "Impact of Sea Level Rise in the New York City Metropolitan Area" (PDF). Global and Planetary Change. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "Many Low-Lying Atoll Islands Will Be Uninhabitable by Mid-21st Century | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ISSN 2072-4292.

- S2CID 244271480.

- ^ Megan Angelo (1 May 2009). "Honey, I Sunk the Maldives: Environmental changes could wipe out some of the world's most well-known travel destinations". Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ Kristina Stefanova (19 April 2009). "Climate refugees in Pacific flee rising sea". The Washington Times.

- ^ Klein, Alice. "Five Pacific islands vanish from sight as sea levels rise". New Scientist. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- Wikidata Q29028186.

- ^ Nurse, Leonard A.; McLean, Roger (2014). "29: Small Islands" (PDF). In Barros, VR; Field (eds.). AR5 WGII. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ^ a b c Grecequet, Martina; Noble, Ian; Hellmann, Jessica (2017-11-16). "Many small island nations can adapt to climate change with global support". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ^ Nations, United. "Small Islands, Rising Seas". United Nations. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ Caramel, Laurence (July 1, 2014). "Besieged by the rising tides of climate change, Kiribati buys land in Fiji". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- S2CID 150286287.

- ^ "Adaptation to Sea Level Rise". UN Environment. 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ Cooley, S., D. Schoeman, L. Bopp, P. Boyd, S. Donner, D.Y. Ghebrehiwet, S.-I. Ito, W. Kiessling, P. Martinetto, E. Ojea, M.-F. Racault, B. Rost, and M. Skern-Mauritzen, 2022: Ocean and Coastal Ecosystems and their Services (Chapter 3). In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. - Cross-Chapter Box SLR: Sea Level Rise

- S2CID 244585347.

- ^ "Climate Adaptation and Sea Level Rise". US EPA, Climate Change Adaptation Resource Center (ARC-X). 2 May 2016.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Cameron (2013). "Costs and coasts: an empirical assessment of physical and institutional climate adaptation pathways". Apo.

- S2CID 153384574. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2020-07-10. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ^ "Coastal cities face rising risk of flood losses, study says". Phys.org. 18 August 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- .

- PMID 36175422.

- doi:10.1038/s43247-023-00703-x..

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - S2CID 256227421.

External links

- Vital signs / Sea level

- Sea level change / Observations from space (links to multiple measurements)

- Fourth National Climate Assessment Sea Level Rise Key Message

- Incorporating Sea Level Change Scenarios at the Local Level Outlines eight steps a community can take to develop site-appropriate scenarios

- The Global Sea Level Observing System (GLOSS)

- USA Sea Level Rise Viewer (NOAA)