Seafood

Seafood is any form of sea life regarded as food by humans, prominently including fish and shellfish. Shellfish include various species of molluscs (e.g., bivalve molluscs such as clams, oysters, and mussels.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The harvesting, processing, and consuming of seafoods are ancient practices with archaeological evidence dating back well into the

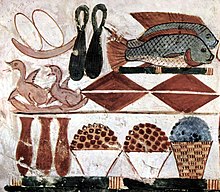

The ancient river Nile was full of fish; fresh and dried fish were a staple food for much of the population.[8] The Egyptians had implements and methods for fishing and these are illustrated in tomb scenes, drawings, and papyrus documents. Some representations hint at fishing being pursued as a pastime.

Fishing scenes are rarely represented in

Pictorial evidence of Roman fishing comes from mosaics.[11] At a certain time, the goatfish was considered the epitome of luxury, above all because its scales exhibit a bright red colour when it dies out of water. For this reason, these fish were occasionally allowed to die slowly at the table. There even was a recipe where this would take place in Garo, in the sauce. At the beginning of the Imperial era, however, this custom suddenly came to an end, which is why mullus in the feast of Trimalchio (see the Satyricon) could be shown as a characteristic of the parvenu, who bores his guests with an unfashionable display of dying fish.

In

Modern knowledge of the reproductive cycles of aquatic species has led to the development of hatcheries and improved techniques of fish farming and aquaculture. A better understanding of the hazards of eating raw and undercooked fish and shellfish has led to improved preservation methods and processing.

Types of seafood

The following table is based on the ISSCAAP classification (International Standard Statistical Classification of Aquatic Animals and Plants) used by the

| Group | Image | Subgroup | Description | 2010 production 1000 tonnes[15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

fish

|

Fish (food) . Total for fish:

|

106,639 | ||

|

marine pelagic |

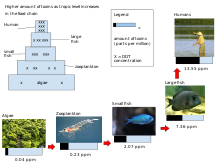

). The smaller forage fish feed on plankton, and can accumulate toxins to a degree. The larger predator fish feed on the forage fish, and accumulate toxins to a much higher degree than the forage fish. | 33,974

| |

|

marine demersal |

Demersal fish live and feed on or near the bottom of the sea.[16] Some seafood groups are cod, flatfish, grouper and stingrays. Demersal fish feed mainly on crustaceans they find on the sea floor, and are more sedentary than the pelagic fish. Pelagic fish usually have the red flesh characteristic of the powerful swimming muscles they need, while demersal fish usually have white flesh. | 23,806

| |

diadromous

|

. | 5,348

| ||

|

freshwater | Freshwater fish live in rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and ponds. Some seafood groups are carp, tilapia, catfish, bass, and trout. Generally, freshwater fish lend themselves to fish farming more readily than the ocean fish, and the larger part of the tonnage reported here refers to farmed fish. | 43,511

| |

molluscs

|

gastropods are protected by a calcareous shell which grows as the mollusc grows. Total for molluscs: Total for molluscs:

|

20,797

| ||

|

bivalves

|

Bivalves, sometimes referred to as clams, have a protective shell in two hinged parts. A valve is the name used for the protective shell of a bivalve, so bivalve literally means two shells. Important seafood bivalves include oysters, scallops, mussels and cockles. Most of these are filter feeders which bury themselves in sediment on the seabed where they are safe from predation. Others lie on the sea floor or attach themselves to rocks or other hard surfaces. Some, such as scallops, can swim. Bivalves have long been a part of the diet of coastal communities. Oysters were cultured in ponds by the Romans and mariculture has more recently become an important source of bivalves for food.

|

12,585 | |

|

gastropods

|

Aquatic gastropods, also known as sea snails, are univalves which means they have a protective shell that is in a single piece. Gastropod literally means stomach-foot, because they appear to crawl on their stomachs. Common seafood groups are abalone, conch, limpets, whelks and periwinkles .

|

526 | |

|

cephalopods | Cephalopods, except for Octopus (food) .

|

3,653 | |

| other | Molluscs not included above are chitons | 4,033 | ||

| crustaceans | knight's armour. The shells do not grow, and must periodically be shed or moulted. Usually two legs or limbs issue from each segment. Most commercial crustaceans are decapods, that is they have ten legs, and have compound eyes set on stalks . Their shell turns pink or red when cooked.Total for crustaceans:

|

11,827 | ||

|

shrimps | . | 6,917 | |

|

crabs | Crabs are stalk-eyed ten-legged crustaceans, usually walk sideways, and have grasping claws as their front pair of limbs. They have small abdomens, short antennae, and a short carapace that is wide and flat. Also usually included are king crabs and coconut crabs, even if these belongs to a different group of decapods than the true crabs. See: crab fisheries. | 1,679[19] | |

|

lobsters | Clawed lobsters and spiny lobsters are stalk-eyed ten-legged crustaceans with long abdomens. The clawed lobster has large asymmetrical claws for its front pair of limbs, one for crushing and one for cutting (pictured). The spiny lobster lacks the large claws, but has a long, spiny antennae and a spiny carapace. Lobsters are larger than most shrimp or crabs. See: lobster fishing .

|

281[20] | |

|

krill | fish feed and for extracting oil. Krill oil contains omega-3 fatty acids, similarly to fish oil. See: Krill fishery .

|

215 | |

| other | Crustaceans not included above are gooseneck barnacles, giant barnacle, mantis shrimp and brine shrimp[22] | 1,359 | ||

| other aquatic animals | Total for other aquatic animals:

|

1409+ | ||

|

aquatic mammals | Faroe Islands, dolphins are traditionally considered food, and are killed in harpoon or drive hunts.[29] Ringed seals are still an important food source for the people of Nunavut[30] and are also hunted and eaten in Alaska.[31] The meat of sea mammals can be high in mercury, and may pose health dangers to humans when consumed.[32] The FAO record only the reported numbers of aquatic mammals harvested, and not the tonnage. In 2010, they reported 2500 whales, 12,000 dolphins and 182,000 seals. See: marine mammals as food, whale meat, seal hunting .

|

? | |

|

aquatic reptiles | critically endangered.[36]

|

296+ | |

|

echinoderms | 373 | ||

|

jellyfish | scyphozoan jellyfish belonging to the order Rhizostomeae are harvested for food; about 12 of the approximately 85 species. Most of the harvest takes place in southeast Asia.[41][42][43]

|

404

| |

|

other | Aquatic animals not included above, such as waterfowl, frogs, spoon worms, peanut worms, palolo worms, lamp shells, lancelets, sea anemones and sea squirts (pictured). | 336 | |

microphytes

|

Total for aquatic plants and microphytes:

|

19,893 | ||

|

seaweed | Seaweed is a loose colloquial term which lacks a formal definition. Broadly, the term is applied to the larger, green algae.[44] Edible seaweeds usually contain high amounts of fibre and, in contrast to terrestrial plants, contain a complete protein.[45] Seaweeds are used extensively as food in coastal cuisines around the world. Seaweed has been a part of diets in China, Japan, and Korea since prehistoric times.[46] Seaweed is also consumed in many traditional European societies, in Iceland and western Norway, the Atlantic coast of France, northern and western Ireland, Wales and some coastal parts of South West England,[47] as well as Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. See: edible seaweed, seaweed farming, aquaculture of giant kelp, laverbread .

|

||

|

microphytes

|

Microalgae are another type of aquatic plant, and includes species that can be consumed by humans and animals. Some species of aquatic bacteria can also be used as seafood, such as spirulina (pictured in tablet form), a type of cyanobacteria. See: culture of microalgae in hatcheries .

|

||

|

aquatic plants

|

Edible aquatic plants are flowering plants and ferns that have adapted to a life in water. Known examples are duck potato, water chestnut, cattail, watercress, lotus and nardoo. | ||

| Total production (thousand tonnes) | 168,447 | |||

Processing

Fish is a highly perishable product: the "fishy" smell of dead fish is due to the breakdown of amino acids into biogenic amines and ammonia.[48]

Live

If the

Because fresh fish is highly perishable, it must be eaten promptly or discarded; it can be kept for only a short time. In many countries, fresh fish are

Long term preservation of fish is accomplished in a variety of ways. The oldest and still most widely used techniques are drying and salting. Desiccation (complete drying) is commonly used to preserve fish such as cod. Partial drying and salting are popular for the preservation of fish like herring and mackerel. Fish such as salmon, tuna, and herring are cooked and canned. Most fish are filleted before canning, but some small fish (e.g. sardines) are only decapitated and gutted before canning.[53]

Consumption

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Seafood is consumed all over the world; it provides the world's prime source of high-quality protein: 14–16% of the animal protein consumed worldwide; over one billion people rely on seafood as their primary source of animal protein.[54][55] Fish is among the most common food allergens.

Since 1960, annual global seafood consumption has more than doubled to over 20 kg per capita. Among the top consumers are Korea (78.5 kg per head), Norway (66.6 kg) and Portugal (61.5 kg).[56]

The UK Food Standards Agency recommends that at least two portions of seafood should be consumed each week, one of which should be oil-rich. There are over 100 different types of seafood available around the coast of the UK.

Oil-rich fish such as

Whitefish such as haddock and cod are very low in fat and calories which, combined with oily fish rich in

Texture and taste

Over 33,000 species of fish and many more marine invertebrate species have been identified.[59] Bromophenols, which are produced by marine algae, give marine animals an odor and taste that is absent from freshwater fish and invertebrates. Also, a chemical substance called dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) that is found in red and green algae is transferred into animals in the marine food chain. When broken down, dimethyl sulfide (DMS) is produced, and is often released during food preparation when fresh fish and shellfish are heated. In small quantities it creates a specific smell one associates with the ocean, but in larger quantities gives the impression of rotten seaweed and old fish.[60] Another molecule known as TMAO occurs in fishes and gives them a distinct smell. It also exists in freshwater species, but becomes more numerous in the cells of an animal the deeper it lives, so fish from the deeper parts of the ocean have a stronger taste than species that live in shallow water.[61] Eggs from seaweed contain sex pheromones called dictyopterenes, which are meant to attract the sperm. These pheromones are also found in edible seaweeds, which contributes to their aroma.[62]

| Common species used as seafood[63] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild flavour | Moderate flavour | Full flavour | |

| Delicate texture |

sea urchin

|

Atlantic mackerel | |

| Medium texture |

bay scallop, Chinese white shrimp

|

sablefish, Atlantic salmon, coho salmon, skate, dungeness crab, king crab, blue mussel, greenshell mussel, pink shrimp | escolar, chinook salmon, chum salmon, American shad |

| Firm texture |

Pacific white shrimp, squid

|

sea scallop, rock shrimp

|

mullet, sockeye salmon, bluefin tuna

|

Health benefits

There is broad scientific consensus that docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) found in seafood are beneficial to neurodevelopment and cognition, especially at young ages.[64][65] The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has described fish as "nature's super food."[66] Seafood consumption is associated with improved neurologic development during pregnancy[67][68] and early childhood[69] and is more tenuously linked to reduced mortality from coronary heart disease.[70]

Fish consumption has been associated with a decreased risk of dementia, lung cancer and stroke.[71][72][73] A 2020 umbrella review concluded that fish consumption reduces all-cause mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke and other outcomes. The review suggested that two to four servings per week is generally safe.[74] However, two other recent umbrella reviews have found no statistically significant associations between fish consumption and cancer risks and have cautioned researchers when it comes to interpreting reported associations between fish consumption and cancer risks because the quality of evidence is very low.[75][76]

The parts of fish containing essential fats and micronutrients, often cited as primary health benefits of eating seafood, are frequently discarded in the developed world.[77] Micronutrients including calcium, potassium, selenium, zinc, and iodine are found in their highest concentrations in the head, intestines, bones, and scales.[78]

Government recommendations promote moderate consumption of fish. The US Food and Drug Administration recommends moderate (4 oz for children and 8–12 oz for adults, weekly) consumption of fish as part of a healthy and balanced diet.[79] The UK National Health Service gives similar advice, recommending at least 2 portions (about 10 oz) of fish weekly.[80] The Chinese National Health Commission recommends slightly more, advising 10–20 oz of fish weekly.[81]

Health hazards

There are numerous factors to consider when evaluating health hazards in seafood. These concerns include marine toxins, microbes, foodborne illness, radionuclide contamination, and man-made pollutants.[77] Shellfish are among the more common food allergens.[82] Most of these dangers can be mitigated or avoided with accurate knowledge of when and where seafood is caught. However, consumers have limited access to relevant and actionable information in this regard and the seafood industry's systemic problems with mislabelling make decisions about what is safe even more fraught.[83]

Scombroid food poisoning, is also a seafood illness. It is typically caused by eating fish high in histamine from being stored or processed improperly.[87]

Man-made disasters can cause localized hazards in seafood which may spread widely via piscine food chains. The first occurrence of widespread

A widely cited study in

"The benefits of modest fish consumption (1-2 servings/wk) outweigh the risks among adults and, excepting a few selected fish species, among women of childbearing age. Avoidance of modest fish consumption due to confusion regarding risks and benefits could result in thousands of excess CHD [congenital heart disease] deaths annually and suboptimal neurodevelopment in children."[70]

Mislabelling

Due to the wide array of options in the seafood marketplace, seafood is far more susceptible to mislabeling than terrestrial food.[77] There are more than 1,700 species of seafood in the United States' consumer marketplace, 80 - 90% of which are imported and less than 1% of which are tested for fraud.[92] However, more recent research into seafood imports and consumption patterns among consumers in the United States suggests that 35%-38% of seafood products are of domestic origin.[94] consumption suggests Estimates of mislabelled seafood in the United States range from 33% in general up to 86% for particular species.[92]

Byzantine supply chains, frequent bycatch, brand naming, species substitution, and inaccurate ecolabels all contribute to confusion for the consumer.[95] A 2013 study by Oceana found that one third of seafood sampled from the United States was incorrectly labeled.[92] Snapper and tuna were particularly susceptible to mislabelling, and seafood substitution was the most common type of fraud. Another type of mislabelling is short-weighting, where practices such as overglasing or soaking can misleadingly increase the apparent weight of the fish.[96] For supermarket shoppers, many seafood products are unrecognisable fillets. Without sophisticated DNA testing, there is no foolproof method to identify a fish species without their head, skin, and fins. This creates easy opportunities to substitute cheap products for expensive ones, a form of economic fraud.[97]

Beyond financial concerns, significant health risks arise from hidden pollutants and marine toxins in an already fraught marketplace. Seafood fraud has led to widespread keriorrhea due to mislabeled escolar, mercury poisoning from products marketed as safe for pregnant women, and hospitalisation and neurological damage due to mislabeled pufferfish.[93] For example, a 2014 study published in PLOS One found that 15% of MSC certified Patagonian toothfish originated from uncertified and mercury polluted fisheries. These fishery-stock substitutions had 100% more mercury than their genuine counterparts, "vastly exceeding" limits in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia.[98]

Sustainability

Research into population trends of various species of seafood is pointing to a global collapse of seafood species by 2048. Such a collapse would occur due to pollution and overfishing, threatening oceanic ecosystems, according to some researchers.[99]

A major international scientific study released in November 2006 in the journal Science found that about one-third of all fishing stocks worldwide have collapsed (with a collapse being defined as a decline to less than 10% of their maximum observed abundance), and that if current trends continue all fish stocks worldwide will collapse within fifty years.[100] In July 2009, Boris Worm of Dalhousie University, the author of the November 2006 study in Science, co-authored an update on the state of the world's fisheries with one of the original study's critics, Ray Hilborn of the University of Washington at Seattle. The new study found that through good fisheries management techniques even depleted fish stocks can be revived and made commercially viable again.[101] An analysis published in August 2020 indicates that seafood could theoretically increase sustainably by 36–74% by 2050 compared to current yields and that whether or not these production potentials are realised sustainably depends on several factors "such as policy reforms, technological innovation, and the extent of future shifts in demand".[102][103]

The

The National Fisheries Institute, a trade advocacy group representing the United States seafood industry, disagree. They claim that currently observed declines in fish populations are due to natural fluctuations and that enhanced technologies will eventually alleviate whatever impact humanity is having on oceanic life.[105]

In religion

For the most part

In the

See also

- Cold chain

- Culinary name

- Fish as food

- Fish processing

- Fish market

- Friend of the Sea

- Got Mercury?

- Jellyfish as food

- List of fish dishes

- List of foods

- List of harvested aquatic animals by weight

- List of seafood companies

- List of seafood dishes

- List of seafood restaurants

- Oyster bar

- Raw bar

- Safe Harbor Certified Seafood

- Seafood Watch, sustainable consumer guide (USA)

References

Citations

- ^ Fish and seafood consumption Our World in Data

- ^ a b Inman, Mason (17 October 2007). "African Cave Yields Earliest Proof of Beach Living". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007.

- ^ African Bone Tools Dispute Key Idea About Human Evolution National Geographic News article.

- ^ "Neanderthals ate shellfish 150,000 years ago: study". Phys.org. 15 September 2011.

- PMID 19581579.

- PhysOrg.com, 6 July 2009.

- ^ Coastal Shell Middens and Agricultural Origins in Atlantic Europe.

- ^ "Fisheries history: Gift of the Nile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2006.

- ^ a b Based on data extracted from the FAO FishStat database 22 July 2012.

- ^ Dalby, p.67.

- ^ Image of fishing illustrated in a Roman mosaic Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Adamson (2002), p. 11.

- ^ Adamson (2004), pp. 45–39.

- ^ "ASFIS List of Species for Fishery Statistics Purposes". Fishery Fact Sheets. Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^

- ^ Walrond C Carl . "Coastal fish – Fish of the open sea floor" Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009

- ^ "Definition of calamari". Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. 18 August 2023.

- ISBN 9780137009725.

- ^ Includes crabs, sea spiders, king crabs and squat lobsters

- ^ Includes lobsters, spiny-rock lobsters

- ^ ISBN 978-92-5-104012-6.

- ^ "Brine Shrimp Artemia as a Direct Human Food" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- PMID 21808012.

- ^ "Native Alaskans say oil drilling threatens way of life". BBC News. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ Nguyen, Vi (26 November 2010). "Warning over contaminated whale meat as Faroe Islands' killing continues". The Ecologist.

- ^ "Greenpeace: Stores, eateries less inclined to offer whale". The Japan Times Online. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (11 March 2010). "What Does Whale Taste Like?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ Kershaw 1988, p.67

- ^

Matsutani, Minoru (23 September 2009). "Details on how Japan's dolphin catches work". Japan Times. p. 3.

- ^ "Eskimo Art, Inuit Art, Canadian Native Artwork, Canadian Aboriginal Artwork". Inuitarteskimoart.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ "Seal Hunt Facts". Sea Shepherd. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^

Johnston, Eric (23 September 2009). "Mercury danger in dolphin meat". Japan Times. p. 3.

- JSTOR 595986.

- ^ CITES (14 June 2006). "Appendices". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. Archived from the original (SHTML) on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- ^ Settle, Sam (1995). "Status of Nesting Populations of Sea Turtles in Thailand and Their Conservation". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 68: 8–13.

- ^ International Union for the Conservation of Nature. "IUCN Red List of Endangered Species". Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ Ess, Charlie. "Wild product's versatility could push price beyond $2 for Alaska dive fleet". National Fisherman. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ Rogers-Bennett, Laura, "The Ecology of Strongylocentrotus franciscanus and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus" in John M. Lawrence, Edible sea urchins: biology and ecology, p. 410

- Oxford Companion to Food, s.v. sea urchin

- ^ Lawrence, John M., "Sea Urchin Roe Cuisine" in John M. Lawrence, Edible sea urchins: biology and ecology

- S2CID 6518460.

- S2CID 20719121.

- PMID 15228981.

- ^ Smith, G.M. 1944. Marine Algae of the Monterey Peninsula, California. Stanford Univ., 2nd Edition.

- .

- ^ "Seaweed as Human Food". Michael Guiry's Seaweed Site. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Spotlight presenters in a lather over laver". BBC. 25 May 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ N. Narain and Nunes, M.L. Marine Animal and Plant Products. In: Handbook of Meat, Poultry and Seafood Quality, L.M.L. Nollet and T. Boylston, eds. Blackwell Publishing 2007, p 247.

- ^ "WIPO". Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ The World Resources Institute, The live reef fish trade Archived 7 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "La Rosa Logistics Inc 14-Jan-03". Fda.gov. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- PMID 28231165.

- PMID 34828803.

- ^ World Health Organization [1].

- PMID 11713181.

- ^ How much fish do we consume? First global seafood consumption footprint published European Commission science and knowledge service. Last update: 27/ September 2018.

- ^ Slovenko R (2001) "Aphrodisiacs-Then and Now" Journal of Psychiatry and Law, 29: 103f.

- ISBN 978-0-312-37736-6.

- ^ FishBase: October 2017 update. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "The Science of Seaweeds | American Scientist". 6 February 2017.

- ^ "BBC – Earth – What does it take to live at the bottom of the ocean?".

- ^ "Why Does The Sea Smell Like The Sea? | Popular Science". 19 August 2014.

- ISBN 9780470404164.

- PMID 25357095.

- S2CID 6564743.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016b. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Contributing to Food Security and Nutrition for AIL Rome: FAO.

- S2CID 35798591.

- PMID 15069395.

- S2CID 22517733.

- ^ PMID 17047219.

- S2CID 38143108.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 3983960.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 53719088.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 216445490.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 32207773.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 32488249.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISBN 9781138191860.

- eISSN 2070-6987.

- ^ "Advice About Eating Fish" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. July 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Fish and shellfish". nhs.uk. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "《中国居民膳食指南(2016)》核心推荐_中国居民膳食指南". dg.cnsoc.org. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network. Archived from the originalon 13 June 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- PMID 36969097.

- ISBN 978-0-323-54696-6

- PMID 36733478.

- ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ "Scombroid Fish Poisoning". California Department of Public Health. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- PMID 30116998.

- ISSN 1369-1465.

- S2CID 241941148.

- OCLC 49526684.

- ^ )

- ^ S2CID 3788104.

- PMID 31068476.

- ISSN 0308-597X.

- ^ "FishWatch – Fraud". Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (3 November 2018). "Seafood Species Substitution and Economic Fraud". FDA.

- PMID 25093736.

- ^ World Seafood Supply Could Run Out by 2048 Researchers Warn boston.com. Retrieved 6 February 2007

- ^ "'Only 50 years left' for sea fish", BBC News. 2 November 2006.

- ^ Study Finds Hope in Saving Saltwater Fish The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2009

- ^ "Food from the sea: Sustainably managed fisheries and the future". phys.org. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- S2CID 221179212.

- ^ "The Status of the Fishing Fleet". The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: 2004. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Seafood Could Collapse by 2050, Experts Warn, NBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ^ Is seafood Haram or Halal? Questions on Islam. Updated 23 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Yoreh De'ah – Shulchan-Aruch Archived 3 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chapter 1, torah.org. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "All that are in the waters: all that... hath not fins and scales ye may not eat" (Deuteronomy 14:9–10) and are "an abomination" (Leviticus 11:9–12).

- ISBN 9780791490679.

- ^ "Summa Theologica Q147a8". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Walkup, Carolyn (8 December 2003). "You can take the girl out of Wisconsin, but the lure of its food remains". Nation's Restaurant News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- Washington Post. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Carlino, Bill (19 February 1990). "Seafood promos aimed to 'lure' Lenten observers". Nation's Restaurant News. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

Sources

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004) Food in Medieval Times Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32147-7.

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2002) Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays Routledge. ISBN 9780415929943.

- Alasalvar C, Miyashita K, Shahidi F and Wanasundara U (2011) Handbook of Seafood Quality, Safety and Health Applications John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444347760.

- Athenaeus of Naucratis The Deipnosophists; or, Banquet of the learned Vol 3, Charles Duke Yonge (trans) 1854. H.G. Bohn.

- ISBN 0-415-15657-2.

- Granata LA, Flick GJ Jr and Martin RE (eds) (2012) The Seafood Industry: Species, Products, Processing, and Safety John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118229538.

- Green, Aliza (2007) Field Guide to Seafood: How to Identify, Select, and Prepare Virtually Every Fish and Shellfish at the Market Quirk Books. ISBN 9781594741357.

- McGee, Harold (2004) On Food And Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684800011.

- Peterson, James and editors of Seafood Business (2009) Seafood Handbook: The Comprehensive Guide to Sourcing, Buying and Preparation John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470404164.

- Potter, Jeff (2010) Cooking for Geeks: Real Science, Great Hacks, and Good Food O'Reilly Media. ISBN 9780596805883.

- Silverstein, Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia B. & Silverstein, Robert A. (1995). The Sea Otter. Brookfield, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, Inc. OCLC 30436543.

- Regensteinn J M and Regensteinn C E (2000) "Religious food laws and the seafood industry" In: R E Martin, E P Carter, G J Flick Jr and L M Davis (Eds) (2000) Marine and freshwater products handbook, CRC Press. ISBN 9781566768894.

- ISBN 9781579583804.

- Stickney, Robert (2009) Aquaculture: An Introductory Text CABI. ISBN 9781845935894.

- Tidwell, James H.; Allan, Geoff L. (2001). "Fish as food: aquaculture's contribution Ecological and economic impacts and contributions of fish farming and capture fisheries". EMBO Reports. 2 (11): 958–963. PMID 11713181.

Further reading

- Alasalvar C, Miyashita K, Shahidi F and Wanasundara U (2011) Handbook of Seafood Quality, Safety and Health Applications, ISBN 9781444347760.

- Ainsworth, Mark (2009) Fish and Seafood: Identification, Fabrication, Utilization Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781435400368.

- Anderson, James L (2003) The International Seafood Trade Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 9781855734562.

- Babal, Ken (2010) Seafood Sense: The Truth about Seafood Nutrition and Safety ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 9781458755995.

- Botana, Luis M (2000) Seafood and Freshwater Toxins: Pharmacology, Physiology and Detection CRC Press. ISBN 9780824746339.

- Boudreaux, Edmond (2011) The Seafood Capital of the World: Biloxi's Maritime History The History Press. ISBN 9781609492847.

- Granata LA, Martin RE and Flick GJ Jr (2012) The Seafood Industry: Species, Products, Processing, and Safety John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118229538.

- Greenberg, Paul (2015). American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0143127437.

- Luten, Joop B (Ed.) (2006) Seafood Research From Fish To Dish: Quality, Safety and Processing of Wild and Farmed Fish Wageningen Academic Pub. ISBN 9789086860050.

- McDermott, Ryan (2007) Toward a More Efficient Seafood Consumption Advisory ProQuest. ISBN 9780549183822.

- Nesheim MC and Yaktine AL (Eds) (2007) Seafood Choices: Balancing Benefits and Risks National Academies Press. ISBN 9780309102186.

- Shames, Lisa (2011) Seafood Safety: FDA Needs to Improve Oversight of Imported Seafood and Better Leverage Limited Resources DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9781437985948.

- Robson, A. (2006). "Shellfish view of omega-3 and sustainable fisheries". Nature. 444 (7122): 1002. doi:10.1038/4441002d.

- Trewin C and Woolfitt A (2006) Cornish Fishing and Seafood Alison Hodge Publishers. ISBN 9780906720424.

- UNEP/Earthprint

- Upton, Harold F (2011) Seafood Safety: Background Issues DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9781437943832.