Second Partition of Poland

| Second Partition of Poland | |

|---|---|

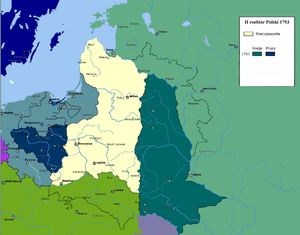

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth after the Second Partition (1793) | |

| Cumulative losses | |

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth after the first two partitions | |

| Territorial losses | |

| Total | 307,000 km2[1] |

| To Prussia | 58,000 km2[2] |

| To Russia | 250,000 km2 |

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of

Background

By 1790, on the political front, the Commonwealth had deteriorated into such a helpless condition that it was forced into an alliance with its enemy, Prussia. The

During the Polish–Russian War of 1792 in Defense of the Constitution, the Polish forces supporting the Constitution fought against the Imperial Russian Army, invited by the pro-Russian alliance of Polish magnates, known as the Targowica Confederation. The conservative nobility (see also, szlachta) believed that the Russians would help them restore their Golden Liberty.[4][5] Abandoned by their Prussian allies, the badly outnumbered Polish pro-Constitution forces fought under Prince Józef Poniatowski a defensive war with some measure of success, but were ordered to abandon their efforts by their supreme commander, King Stanisław August Poniatowski. The King decided to join the Targowica Confederation, as demanded by the Russians.[4][5]

Russia invaded Poland to ensure the defeat of the Polish reforms, with no overt goal of another partition (it viewed Poland as its

Partition treaty

On 23 January 1793, Prussia signed a treaty with Russia, agreeing that Polish reforms would be revoked and both countries would receive broad swaths of Commonwealth territory.[5] Russian and Prussian troops took control of the territories they claimed, with Russian troops already present, and Prussian troops meeting only limited resistance.[4][5] In 1793, deputies to the Grodno Sejm, the last Sejm of the Commonwealth, in the presence of Russian forces, agreed to the Russian and Prussian territorial demands. The Grodno Sejm became infamous not only as the last sejm of the Commonwealth, but because its deputies had been bribed and coerced by the Russians (Russia and Prussia wanted legal sanction from Poland for their demands).[4][8]

Imperial Russia annexed 250,000 square kilometres (97,000 sq mi), while Prussia took 58,000 square kilometres (22,000 sq mi).[2] The Commonwealth lost about 307,000 km2, being reduced to 215,000 km2.[1][9]

Russian Partition

Prussian Partition

The Commonwealth lost about 5 million people; only about 4 million people remained in the Polish–Lithuanian lands.[5][15]

What was left of the Commonwealth was a small buffer state with a puppet king, and Russian garrisons keeping an eye on the reduced army.[9][16][17]

Aftermath

Targowica confederates, who did not expect another partition, and the king, Stanisław August Poniatowski, who joined them near the end, both lost much prestige and support.[4][5] The reformers, on the other hand, were attracting increasing support.[11] In March 1794 the Kościuszko Uprising began. The defeat of the Uprising in November that year resulted in the final Third Partition of Poland, ending the existence of the Commonwealth.[4]

See also

- Administrative division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealthin the course of partitions

- Administrative division of Polish territories after partitions

- Third Partition of Poland

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-415-25490-8. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Henry Smith Williams (1904). The Historians' History of the World: Poland, The Balkans, Turkey, Minor eastern states, China, Japan. Outlook Company. pp. 88–91. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-521-79269-1. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-06-097468-8. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Adam Nowicki (1945). Dzieje Polski: od czasów najdawniejszych do chwili bieżącej. Księgarnia Polska. p. 152. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-83-7006-400-6. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Сергей А. Тархов. "Изменение административно-территориального деления за последние 300 лет". (Sergey A. Tarkhov. Changes of the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Russia in the past 300 years).

- ISBN 978-0-19-161046-2. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ William Fiddian Reddaway (1971). The Cambridge History of Poland. CUP Archive. p. 152. GGKEY:2G7C1LPZ3RN. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ William Fiddian Reddaway (1971). The Cambridge History of Poland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 157–159. GGKEY:2G7C1LPZ3RN. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-375-41197-7. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

Further reading

- Tadeusz Cegielski, Łukasz Kądziela, Rozbiory Polski 1772–1793–1795, Warszawa 1990 [ISBN missing]