Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | |

|---|---|

N06AB | |

| Biological target | Serotonin transporter |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| Consumer Reports | Best Buy Drugs |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D017367 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a

SSRIs increase the

SSRIs are the most widely prescribed antidepressants in many countries.[3] The efficacy of SSRIs in mild or moderate cases of depression has been disputed[4] and may or may not be outweighed by side effects, especially in adolescent populations.[5][6][7][8]

Medical uses

The main indication for SSRIs is

Depression

Antidepressants are recommended by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a first-line treatment of severe depression and for the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression that persists after conservative measures such as cognitive therapy.[10] They recommend against their routine use by those who have chronic health problems and mild depression.[10]

There has been controversy regarding the efficacy of SSRIs in treating depression depending on its severity and duration.

- Two meta-analyses published in 2008 (Kirsch) and 2010 (Fournier) found that in mild and moderate depression, the effect of SSRIs is small or none compared to placebo, while in very severe depression the effect of SSRIs is between "relatively small" and "substantial".[6][11] The 2008 meta-analysis combined 35 clinical trials submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before licensing of four newer antidepressants (including the SSRIs paroxetine and fluoxetine, the non-SSRI antidepressant nefazodone, and the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine). The authors attributed the relationship between severity and efficacy to a reduction of the placebo effect in severely depressed patients, rather than an increase in the effect of the medication.[11] Some researchers have questioned the statistical basis of this study suggesting that it underestimates the effect size of antidepressants.[12][13]

- A 2012 meta-analysis of fluoxetine and venlafaxine concluded that statistically and clinically significant treatment effects were observed for each drug relative to placebo irrespective of baseline depression severity; some of the authors however disclosed substantial relationships with pharmaceutical industries.[14]

- A 2017 systematic review stated that "SSRIs versus placebo seem to have statistically significant effects on depressive symptoms, but the clinical significance of these effects seems questionable and all trials were at high risk of bias. Furthermore, SSRIs versus placebo significantly increase the risk of both serious and non-serious adverse events. Our results show that the harmful effects of SSRIs versus placebo for major depressive disorder seem to outweigh any potentially small beneficial effects".[8] Fredrik Hieronymus et al. criticized the review as inaccurate and misleading, but they also disclosed multiple ties to pharmaceutical industries and receipt of speaker's fees.[15]

- In 2018, a systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs showed escitalopram to be one of the most effective. They showed that "In terms of efficacy, all antidepressants were more effective than placebo, with odds ratios (ORs) ranging between 2.13 (95% credible interval [CrI] 1.89–2.41) for amitriptyline and 1.37 (1.16–1.63) for reboxetine."[16]

The use of SSRIs in children with depression remains controversial. A 2021 Cochrane review concluded that, for children and adolescents, SSRIs "may reduce depression symptoms in a small and unimportant way compared with placebo."[17] However, it also noted significant methodological limitations that make drawing definitive conclusions about efficacy difficult. Fluoxetine is the only SSRI authorized for use in children and adolescents with moderate to severe depression in the United Kingdom.[18]

Social anxiety disorder

Some SSRIs are effective for

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder

SSRIs are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) that has failed to respond to conservative measures such as education and self-help activities. GAD is a common disorder of which the central feature is excessive worry about a number of different events. Key symptoms include excessive anxiety about multiple events and issues, and difficulty controlling worrisome thoughts, that persists for at least 6 months.

Antidepressants provide a modest-to-moderate reduction in anxiety in GAD,[22] and are superior to placebo in treating GAD. The efficacy of different antidepressants is similar.[22]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

In Canada, SSRIs are a first-line treatment of adult obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). In the UK, they are first-line treatment only with moderate to severe functional impairment and as second line treatment for those with mild impairment, though, as of early 2019, this recommendation is being reviewed.[23] In children, SSRIs can be considered a second line therapy in those with moderate-to-severe impairment, with close monitoring for psychiatric adverse effects.[24] SSRIs, especially fluvoxamine, which is the first one to be FDA approved for OCD, are efficacious in its treatment; patients treated with SSRIs are about twice as likely to respond to treatment as those treated with placebo.[25][26] Efficacy has been demonstrated both in short-term treatment trials of 6 to 24 weeks and in discontinuation trials of 28 to 52 weeks duration.[27][28][29]

Panic disorder

Paroxetine CR was superior to placebo on the primary outcome measure. In a 10-week randomized controlled, double-blind trial escitalopram was more effective than placebo.[30] Fluvoxamine, another SSRI, has shown positive results.[31] However, evidence for their effectiveness and acceptability is unclear.[32]

Eating disorders

Antidepressants are recommended as an alternative or additional first step to self-help programs in the treatment of bulimia nervosa.[33] SSRIs (fluoxetine in particular) are preferred over other anti-depressants due to their acceptability, tolerability, and superior reduction of symptoms in short-term trials. Long-term efficacy remains poorly characterized.

Similar recommendations apply to binge eating disorder.[33] SSRIs provide short-term reductions in binge eating behavior, but have not been associated with significant weight loss.[34]

Clinical trials have generated mostly negative results for the use of SSRIs in the treatment of anorexia nervosa.[35] Treatment guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence[33] recommend against the use of SSRIs in this disorder. Those from the American Psychiatric Association note that SSRIs confer no advantage regarding weight gain, but that they may be used for the treatment of co-existing depression, anxiety, or OCD.[34]

Stroke recovery

SSRIs have been used off-label in the treatment of stroke patients, including those with and without symptoms of depression. A 2021 meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials found no evidence pointing to their routine use to promote recovery following stroke.[36]

Premature ejaculation

SSRIs are effective for the treatment of premature ejaculation. Taking SSRIs on a chronic, daily basis is more effective than taking them prior to sexual activity.[37] The increased efficacy of treatment when taking SSRIs on a daily basis is consistent with clinical observations that the therapeutic effects of SSRIs generally take several weeks to emerge.[38] Sexual dysfunction ranging from decreased libido to anorgasmia is usually considered to be a significantly distressing side effect which may lead to noncompliance in patients receiving SSRIs.[39] However, for those with premature ejaculation, this very same side effect becomes the desired effect.

Other uses

SSRIs such as sertraline have been found to be effective in decreasing anger.[40]

Side effects

Side effects vary among the individual drugs of this class. They may include akathisia.[41][42][43][44]

Sexual dysfunction

SSRIs can cause various types of sexual dysfunction such as anorgasmia, erectile dysfunction, diminished libido, genital numbness, and sexual anhedonia (pleasureless orgasm).[45] Sexual problems are common with SSRIs.[46] Poor sexual function is one of the most common reasons people stop the medication.[47]

The mechanism by which SSRIs may cause sexual side effects is not well understood as of 2021[update]. The range of possible mechanisms includes (1) nonspecific neurological effects (e.g., sedation) that globally impair behavior including sexual function; (2) specific effects on brain systems mediating sexual function; (3) specific effects on peripheral tissues and organs, such as the penis, that mediate sexual function; and (4) direct or indirect effects on hormones mediating sexual function.[48] Management strategies include: for erectile dysfunction the addition of a PDE5 inhibitor such as sildenafil; for decreased libido, possibly adding or switching to bupropion; and for overall sexual dysfunction, switching to nefazodone.[49]

A number of non-SSRI drugs are not associated with sexual side effects (such as bupropion, mirtazapine, tianeptine, agomelatine, tranylcypromine and moclobemide[50][51][52]).

Several studies have suggested that SSRIs may adversely affect semen quality.[53]

While

Post-SSRI

Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD)[55][56] refers to a set of symptoms reported by some people who have taken SSRIs or other serotonin reuptake-inhibiting (SRI) drugs, in which sexual dysfunction symptoms persist for at least three months[57][58][59] after ceasing to take the drug. The status of PSSD as a legitimate and distinct pathology is contentious; several researchers have proposed that it should be recognized as a separate phenomenon from more common SSRI side effects.[60]

The reported symptoms of PSSD include reduced

Diagnostic criteria for PSSD were proposed in 2022,[57] but as of 2023, there is no agreement on standards for diagnosis.[56] It is considered a distinct phenomenon from antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, post-acute withdrawal syndrome, and major depressive disorder,[61][60] and should be distinguished from sexual dysfunction associated with depression[61] and persistent genital arousal disorder.[56] There are limited treatment options for PSSD as of 2023 and no evidence that any individual approach is effective.[56] The mechanism by which SRIs may induce PSSD is unclear;[61] neurobiological and cognitive factors may act in combination to cause the problem.[56] As of 2023, prevalence is unknown.[56] A 2020 review stated that PSSD is rare, underreported, and "increasingly identified in online communities".[63]

Reports of PSSD have occurred with almost every SSRI (

Emotional blunting

Certain antidepressants may cause

Vision

Acute narrow-angle glaucoma is the most common and important ocular side effect of SSRIs, and often goes misdiagnosed.[71][72]

Cardiac

SSRIs do not appear to affect the risk of

In a 2023 study a possible connection between SSRI usage and the onset of

Bleeding

SSRIs directly increase the risk of abnormal bleeding by lowering platelet serotonin levels, which are essential to platelet-driven hemostasis.[83] SSRIs interact with

Fracture risk

Evidence from longitudinal, cross-sectional, and prospective cohort studies suggests an association between SSRI usage at therapeutic doses and a decrease in bone mineral density, as well as increased fracture risk,[92][93][94][95] a relationship that appears to persist even with adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy.[96] However, because the relationship between SSRIs and fractures is based on observational data as opposed to prospective trials, the phenomenon is not definitively causal.[97] There also appears to be an increase in fracture-inducing falls with SSRI use, suggesting the need for increased attention to fall risk in elderly patients using the medication.[97] The loss of bone density does not appear to occur in younger patients taking SSRIs.[98]

Bruxism

Serotonin syndrome

Serotonin syndrome is typically caused by the use of two or more

Suicide risk

Children and adolescents

Meta analyses of short duration randomized clinical trials have found that SSRI use is related to a higher risk of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents.

A recent comparison of aggression and hostility occurring during treatment with fluoxetine to placebo in children and adolescents found that no significant difference between the fluoxetine group and a placebo group.[114] There is also evidence that higher rates of SSRI prescriptions are associated with lower rates of suicide in children, though since the evidence is correlational, the true nature of the relationship is unclear.[115]

In 2004, the

Adults

It is unclear whether SSRIs affect the risk of suicidal behavior in adults.

- A 2005 meta-analysis of drug company data found no evidence that SSRIs increased the risk of suicide; however, important protective or hazardous effects could not be excluded.[118]

- A 2005 review observed that suicide attempts are increased in those who use SSRIs as compared to tricyclic antidepressants. No difference risk of suicide attempts was detected between SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants.[119]

- A 2006 review suggests that the widespread use of antidepressants in the new "SSRI-era" appears to have led to a highly significant decline in suicide rates in most countries with traditionally high baseline suicide rates. The decline is particularly striking for women who, compared with men, seek more help for depression. Recent clinical data on large samples in the US too have revealed a protective effect of antidepressant against suicide.[120]

- A 2006 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials suggests that SSRIs increase suicide ideation compared with placebo. However, the observational studies suggest that SSRIs did not increase suicide risk more than older antidepressants. The researchers stated that if SSRIs increase suicide risk in some patients, the number of additional deaths is very small because ecological studies have generally found that suicide mortality has declined (or at least not increased) as SSRI use has increased.[121]

- An additional meta-analysis by the FDA in 2006 found an age-related effect of SSRI's. Among adults younger than 25 years, results indicated that there was a higher risk for suicidal behavior. For adults between 25 and 64, the effect appears neutral on suicidal behavior but possibly protective for suicidal behavior for adults between the ages of 25 and 64. For adults older than 64, SSRI's seem to reduce the risk of both suicidal behavior.[106]

- In 2016 a study criticized the effects of the FDA Black Box suicide warning inclusion in the prescription. The authors discussed the suicide rates might increase also as a consequence of the warning.[122]

Risk of death

A 2017

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

SSRI use in pregnancy has been associated with a variety of risks with varying degrees of proof of causation. As depression is independently associated with negative pregnancy outcomes, determining the extent to which observed associations between antidepressant use and specific adverse outcomes reflects a causative relationship has been difficult in some cases.[124] In other cases, the attribution of adverse outcomes to antidepressant exposure seems fairly clear.

SSRI use in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion of about 1.7-fold.[125][126] Use is also associated with preterm birth.[127] According to some researches, decreased body weight of the child, intrauterine growth retardation, neonatal adaptive syndrome, and persistent pulmonary hypertension also was noted.[128]

A systematic review of the risk of major birth defects in antidepressant-exposed pregnancies found a small increase (3% to 24%) in the risk of major malformations and a risk of cardiovascular birth defects that did not differ from non-exposed pregnancies.[129] [130] Other studies have found an increased risk of cardiovascular birth defects among depressed mothers not undergoing SSRI treatment, suggesting the possibility of ascertainment bias, e.g. that worried mothers may pursue more aggressive testing of their infants.[131] Another study found no increase in cardiovascular birth defects and a 27% increased risk of major malformations in SSRI exposed pregnancies.[126]

The FDA issued a statement on July 19, 2006, stating nursing mothers on SSRIs must discuss treatment with their physicians. However, the medical literature on the safety of SSRIs has determined that some SSRIs like Sertraline and Paroxetine are considered safe for breastfeeding.[132][133][134]

Neonatal abstinence syndrome

Several studies have documented

Persistent pulmonary hypertension

Persistent

Neuropsychiatric effects in offspring

According to a 2015 review available data found that "some signal exists suggesting that

Bipolar switch

In adults and children with

Interactions

The following drugs may precipitate serotonin syndrome in people on SSRIs:[146][147]

- Linezolid

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) including moclobemide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, selegiline and methylene blue

- Lithium

- Sibutramine

- MDMA (ecstasy)

- Dextromethorphan

- Tramadol

- 5-HTP

- Pethidine/meperidine

- St. John's wort

- Yohimbe

- Tricyclic antidepressants(TCAs)

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors(SNRIs)

- Buspirone

- Triptan

- Mirtazapine

- Methylene blue

Painkillers of the NSAIDs drug family may interfere and reduce efficiency of SSRIs and may compound the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeds caused by SSRI use.[85][87][148] NSAIDs include:

There are a number of potential pharmacokinetic interactions between the various individual SSRIs and other medications. Most of these arise from the fact that every SSRI has the ability to inhibit certain P450 cytochromes.[149][150][151]

| Drug name | CYP1A2 | CYP2C9 | CYP2C19 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4 | CYP2B6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Escitalopram | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Fluoxetine | + | ++ | +/++ | +++ | + | + |

| Fluvoxamine | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + |

| Paroxetine | + | + | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Sertraline | + | + | +/++ | + | + | + |

Legend:

0 – no inhibition

+ – mild inhibition

++ – moderate inhibition

+++ – strong inhibition

The CYP2D6 enzyme is entirely responsible for the metabolism of hydrocodone, codeine[152] and dihydrocodeine to their active metabolites (hydromorphone, morphine, and dihydromorphine, respectively), which in turn undergo phase 2 glucuronidation. These opioids (and to a lesser extent oxycodone, tramadol, and methadone) have interaction potential with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.[153][154] The concomitant use of some SSRIs (paroxetine and fluoxetine) with codeine may decrease the plasma concentration of active metabolite morphine, which may result in reduced analgesic efficacy.[155][156]

Another important interaction of certain SSRIs involves paroxetine, a potent inhibitor of CYP2D6, and tamoxifen, an agent used commonly in the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Tamoxifen is a prodrug that is metabolised by the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme system, especially CYP2D6, to its active metabolites. Concomitant use of paroxetine and tamoxifen in women with breast cancer is associated with a higher risk of death, as much as a 91 percent in women who used it the longest.[157]

Overdose

SSRIs appear safer in

Because of the wide therapeutic index of the SSRIs, most patients will have mild or no symptoms following moderate overdoses. The most commonly reported severe effect following SSRI overdose is serotonin syndrome; serotonin toxicity is usually associated with very high overdoses or multiple drug ingestion.[161] Other reported significant effects include coma, seizures, and cardiac toxicity.[158]

Poisoning is also known in animals, and some toxicity information is available for veterinary treatment.[162]

Discontinuation syndrome

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors should not be abruptly discontinued after extended therapy, and whenever possible, should be tapered over several weeks to minimize discontinuation-related symptoms which may include nausea, headache, dizziness, chills, body aches, paresthesias, insomnia, and

Mechanism of action

Serotonin reuptake inhibition

In the

SSRIs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin. As a result, the serotonin stays in the synaptic gap longer than it normally would, and may repeatedly stimulate the receptors of the recipient cell. In the short run, this leads to an increase in signaling across synapses in which serotonin serves as the primary neurotransmitter. On chronic dosing, the increased occupancy of post-synaptic serotonin receptors signals the pre-synaptic neuron to synthesize and release less serotonin. Serotonin levels within the synapse drop, then rise again, ultimately leading to

Owing to the lack of a widely accepted comprehensive theory of the biology of mood disorders, there is no widely accepted theory of how these changes lead to the mood-elevating and anti-anxiety effects of SSRIs.Their effects on serotonin blood levels, which take weeks to take effect, appear to be largely responsible for their slow-to-appear psychiatric effects.[167] SSRIs mediate their action largely with high occupancy in a total of all serotonin transporters within the brain and through this slow downstream changes of large brain regions at therapeutic concentrations, whereas MDMA leads to an excess serotonin release in a short run. This could explain the absence of a "high" by antidepressants and in addition the contrary ability of SSRIs in expressing neuroprotective actions to the neurotoxic abilities of MDMA.[168]

Sigma receptor ligands

| Medication | SERT | σ1 | σ2 | σ1 / SERT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 1.16 | 292–404 | Agonist | 5,410 | 252–348 |

| Escitalopram | 2.5 | 288 | Agonist | ND | ND |

| Fluoxetine | 0.81 | 191–240 | Agonist | 16,100 | 296–365 |

| Fluvoxamine | 2.2 | 17–36 | Agonist | 8,439 | 7.7–16.4 |

| Paroxetine | 0.13 | ≥1,893 | ND | 22,870 | ≥14,562 |

| Sertraline | 0.29 | 32–57 | Antagonist | 5,297 | 110–197 |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||||

In addition to their actions as reuptake inhibitors of serotonin, some SSRIs are also, coincidentally, ligands of the sigma receptors.[169][170] Fluvoxamine is an agonist of the σ1 receptor, while sertraline is an antagonist of the σ1 receptor, and paroxetine does not significantly interact with the σ1 receptor.[169][170] None of the SSRIs have significant affinity for the σ2 receptor.[169][170] Fluvoxamine has by far the strongest activity of the SSRIs at the σ1 receptor.[169][170] High occupancy of the σ1 receptor by clinical dosages of fluvoxamine has been observed in the human brain in positron emission tomography (PET) research.[169][170] It is thought that agonism of the σ1 receptor by fluvoxamine may have beneficial effects on cognition.[169][170] In contrast to fluvoxamine, the relevance of the σ1 receptor in the actions of the other SSRIs is uncertain and questionable due to their very low affinity for the receptor relative to the SERT.[171]

Anti-inflammatory effects

The role of inflammation and the immune system in depression has been extensively studied. The evidence supporting this link has been shown in numerous studies over the past ten years. Nationwide studies and meta-analyses of smaller cohort studies have uncovered a correlation between pre-existing inflammatory conditions such as

SSRIs were originally invented with the goal of increasing levels of available serotonin in the extracellular spaces. However, the delayed response between when patients first begin SSRI treatment to when they see effects has led scientists to believe that other molecules are involved in the efficacy of these drugs.[173] To investigate the apparent anti-inflammatory effects of SSRIs, both Kohler et al. and Więdłocha et al. conducted meta-analyses which have shown that after antidepressant treatment the levels of cytokines associated with inflammation are decreased.[174][175] A large cohort study conducted by researchers in the Netherlands investigated the association between depressive disorders, symptoms, and antidepressants with inflammation. The study showed decreased levels of interleukin (IL)-6, a cytokine that has proinflammatory effects, in patients taking SSRIs compared to non-medicated patients.[176]

Treatment with SSRIs has shown reduced production of inflammatory cytokines such as

In addition to affecting cytokine production, there is evidence that treatment with SSRIs has effects on the proliferation and viability of immune system cells involved in both innate and adaptive immunity. Evidence shows that SSRIs can inhibit proliferation in

The anti-inflammatory effects of SSRIs have prompted studies of the efficacy of SSRIs in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as

Pharmacogenetics

Large bodies of research are devoted to using genetic markers to predict whether patients will respond to SSRIs or have side effects that will cause their discontinuation, although these tests are not yet ready for widespread clinical use.[181]

Versus TCAs

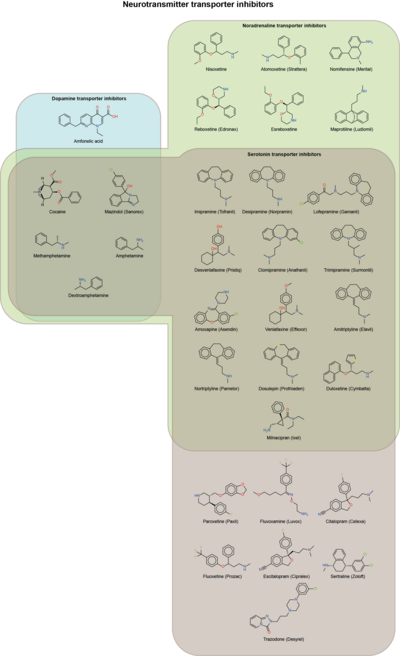

SSRIs are described as 'selective' because they affect only the reuptake pumps responsible for serotonin, as opposed to earlier antidepressants, which affect other monoamine neurotransmitters as well, and as a result, SSRIs have fewer side effects.

There appears to be no significant difference in effectiveness between SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, which were the most commonly used class of antidepressants before the development of SSRIs.[182] However, SSRIs have the important advantage that their toxic dose is high, and, therefore, they are much more difficult to use as a means to commit suicide. Further, they have fewer and milder side effects. Tricyclic antidepressants also have a higher risk of serious cardiovascular side effects, which SSRIs lack.

SSRIs act on signal pathways such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) on the postsynaptic neuronal cell, which leads to the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF enhances the growth and survival of cortical neurons and synapses.[166]

List of SSRIs

Marketed

Antidepressants

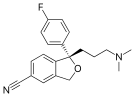

- Citalopram (Celexa)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

- Paroxetine (Paxil)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

Others

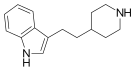

- Dapoxetine (Priligy)

Discontinued

Antidepressants

- Indalpine (Upstène)

- Zimelidine (Zelmid)

Never marketed

Antidepressants

- Alaproclate (GEA-654)

- Centpropazine

- Cericlamine (JO-1017)

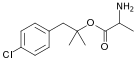

- Femoxetine (Malexil; FG-4963)

- Ifoxetine (CGP-15210)

- Omiloxetine

- Panuramine (WY-26002)

- Pirandamine (AY-23713)

- Seproxetine ((S)-norfluoxetine)

Related drugs

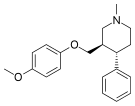

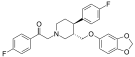

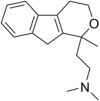

Although described as

History

Fluoxetine was introduced in 1987 and was the first major SSRI to be marketed.

Controversy

A study examining publication of results from FDA-evaluated antidepressants concluded that those with favorable results were much more likely to be published than those with negative results.[193] Furthermore, an investigation of 185 meta-analyses on antidepressants found that 79% of them had authors affiliated in some way to pharmaceutical companies and that they were reluctant to report caveats for antidepressants.[194]

David Healy has argued that warning signs were available for many years prior to regulatory authorities moving to put warnings on antidepressant labels that they might cause suicidal thoughts.[195] At the time these warnings were added, others argued that the evidence for harm remained unpersuasive[196][197] and others continued to do so after the warnings were added.[198][199]

In other organisms

SSRIs are common

Veterinary use

An SSRI (fluoxetine) has been approved for veterinary use in treatment of canine separation anxiety.[201]

See also

- List of antidepressants

- Serotonin releasing agent (SRA)

- Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI)

- Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI)

- Dapoxetine

References

- OCLC 192055408.

- S2CID 4937890. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2019-02-28.

- ISBN 978-3-540-43054-4.

- ^ Psychology today: Depression and Serotonin: What the New Review Actually Says

- ^ Kramer P (7 Sep 2011). "In Defense of Antidepressants". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ PMID 20051569.

- PMID 20520282.

- ^ PMID 28178949.

- .

- ^ a b National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (October 2009). "Depression Quick Reference Guide" (PDF). NICE clinical guidelines 90 and 91. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2013.

- ^ PMID 18303940.

- S2CID 10323933.

- PMID 20800012.

- PMID 22393205.

- PMID 28718394.

- PMID 29477251.

- PMID 34029378.

- ^ "Depression in children and young people: identification and management". NICE guideline NG134. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 2019.

- PMID 22665997.

- S2CID 21795838.

- PMID 22346334.

- ^ a b "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- PMID 25081580.

- ^ "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder" (PDF). November 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- PMID 19588448.

- ^ Busko M (28 February 2008). "Review Finds SSRIs Modestly Effective in Short-Term Treatment of OCD". Medscape. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013.

- PMID 22226028.

- ^ "Sertraline prescribing information" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ^ "Paroxetine prescribing information" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- PMID 21733234.

- S2CID 40412606.

- PMID 29620793.

- ^ a b c "Eating disorders in over 8s: management" (PDF). Clinical guideline [CG9]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). January 2004.

- ^ a b "Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders". National Guideline Clearinghouse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25.

- PMID 21414249.

- PMID 34780067.

- PMID 17983899.

- PMID 27713241.

- PMID 21701626.

- PMID 31126061.

- PMID 21406165.

- S2CID 20944428.

- PMID 19289334.

- PMID 8909330.

- .

- PMID 23728643.

- S2CID 739831.

- PMID 7929021.

- PMID 16946173.

- S2CID 1663570.

- ^ Clayton AH (2003). "Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: A Potentially Avoidable Therapeutic Challenge". Primary Psychiatry. 10 (1): 55–61. Archived from the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- PMID 12429073.

- PMID 22573230.

- S2CID 54621798.

- PMID 33998993.

- ^ S2CID 259126886.

- ^ PMID 34719438.

- ^ S2CID 244347777.

- S2CID 260202178.

- ^ PMID 28778697.

There is still no definitive treatment for PSSD. Low-power laser irradiation and phototherapy have shown some promising results.

- ^ S2CID 238580777.

- S2CID 4974636.

- S2CID 212728659.

- ^ PRAC recommendations on signals: Adopted at the 13-16 May 2019 PRAC meeting (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 11 June 2019. p. 5. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- S2CID 231669986.

- PMID 34908941.

- ^ PMID 34970173.

- PMID 26407780.

- PMID 23823799.

- S2CID 228877905.

- PMID 19587851.

- PMID 26139049.

- PMID 24646010.

- PMID 24941178.

- PMID 9443704.

- ^ FDA (December 2018). "FDA Drug Safety". FDA.

- ^ Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation – new maximum daily dose restrictions (including in elderly patients), contraindications, and warnings. From Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Article date: December 2011

- ^ "Clinical and ECG Effects of Escitalopram Overdose" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- S2CID 28057842.

- ^ "Deciphering the Connection of Serotonin to Degenerative Mitral Valve Regurgitation - Advances in Cardiology and Heart Surgery". NewYork-Presbyterian. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- PMID 36599005.

- ^ "Serotonin can potentially accelerate degenerative mitral regurgitation, study says". News-Medical. 2023-01-29. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- PMID 27514297.

- ^ S2CID 46551382.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-97969-3.

- ^ PMID 21190637.

- ^ PMID 18606952.

- S2CID 11941911.

- PMID 16443409.

- PMID 17506225.

- S2CID 116561324.

- PMID 22258738.

- S2CID 32286954.

- PMID 27055202.

- S2CID 7648524.

- S2CID 20622369.

- ^ S2CID 5610316.

- PMID 23196265.

- PMID 29708207.

- S2CID 148816505.

- PMID 21768799.

- PMID 24358002.

- S2CID 37959124.

- PMID 29482205.

- ISBN 978-0-323-44838-3.

- ^ a b Stone MB, Jones ML (2006-11-17). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidal behavior in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C (2006-11-17). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- PMID 16894062.

- ^ Hammad TA (2004-08-16). "Review and evaluation of clinical data. Relationship between psychiatric drugs and pediatric suicidal behavior" (PDF). FDA. pp. 42, 115. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "Antidepressant Use in Children, Adolescents, and Adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017.

- ^ "FDA Medication Guide for Antidepressants". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ^ PMID 25433518.

- ^ "Overview | Depression in adults: recognition and management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 28 October 2009.

- PMID 17979590.

- S2CID 2390497.

- ^ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. 2004-12-01. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including a summary of available safety and efficacy data". MHRA. 2005-09-29. Archived from the original on 2008-08-02. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- PMID 15718537.

- PMID 15718539.

- PMID 16712945.

- PMID 17054562.

- .

- ^ S2CID 4830115.

- S2CID 22875385.

- PMID 16720091.

- ^ PMID 23351929.

- PMID 27239775.

- PMID 30123033.

- PMID 22946124.

- PMID 23660045.

- PMID 23228547.

- ^ "Breastfeeding Update: SDCBC's quarterly newsletter". Breastfeeding.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Using Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers". kellymom.com. Archived from the original on 2010-09-23. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- S2CID 757921.

- PMID 21893008.

- PMID 24039427.

- ^ Persistent Newborn Pulmonary Hypertension at eMedicine

- PMID 24429387.

- PMID 22564982.

- PMID 25985383.

- S2CID 9064353.

- ^ PMID 27126849.

- PMID 30506151.

- S2CID 25152608.

- PMID 11322738.

- PMID 12873279.

- S2CID 37959124.

- PMID 21518864.

- ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ISBN 978-1-60327-435-7.

- S2CID 19802446.

- PMID 21999760.

- ^ "Paroxetine hydrochloride – Drug Summary". Physicians' Desk Reference, LLC. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- PMID 19567715.

- PMID 28947846.

- PMID 23763556.

- PMID 20142325.

- ^ S2CID 43121327.

- PMID 1586402.

- S2CID 5287418.

- S2CID 19809259.

- ISBN 978-0-12-385926-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-338-7.[page needed]

- PMID 23596418.

- ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ a b Kolb, Bryan and Wishaw Ian. An Introduction to Brain and Behavior. New York: Worth Publishers 2006, Print.

- PMID 23670590.

- S2CID 3322646.

- ^ S2CID 26491662.

- ^ PMID 28315270.

- PMID 20492642.

- PMID 27640518.

- S2CID 21501578.

- S2CID 4040496.

- S2CID 34659323.

- PMID 22832816.

- ^ PMID 27101921.

- ^ PMID 27453459.

- ^ PMID 24613205.

- PMID 31267131.

- S2CID 24257390.

- PMID 10760555.

- ^ a b c d Shelton RC (2009). "Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: similarities and differences". Primary Psychiatry. 16 (4): 25.

- S2CID 24692832.

- ISBN 978-0-7020-7190-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4557-0061-5.

- PMID 26572745.

- ^ PMID 28707591.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-0348-8391-7.

- ^ PMID 17017959.

- ^ ISBN 1-57059-649-2.

- PMID 18199864.

- PMID 26399904.

- S2CID 6599566.

- PMID 14517577.

- S2CID 20755149.

- S2CID 41954145.

- PMID 22309973.

- S2CID 58564142.

- PMID 23796482.