Selenography

Selenography is the study of the surface and physical features of the Moon (also known as geography of the Moon, or selenodesy).[1] Like geography and areography, selenography is a subdiscipline within the field of planetary science. Historically, the principal concern of selenographists was the mapping and naming of the lunar terrane identifying maria, craters, mountain ranges, and other various features. This task was largely finished when high resolution images of the near and far sides of the Moon were obtained by orbiting spacecraft during the early space era. Nevertheless, some regions of the Moon remain poorly imaged (especially near the poles) and the exact locations of many features (like crater depths) are uncertain by several kilometers. Today, selenography is considered to be a subdiscipline of selenology, which itself is most often referred to as simply "lunar science." The word selenography is derived from the Greek word Σελήνη (Selene, meaning Moon) and γράφω graphō, meaning to write.

History

The idea that the Moon is not perfectly smooth originates to at least c. 450 BC, when

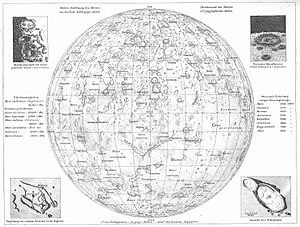

Lunar mapping became systematic in 1779 when Johann Schröter began meticulous observation and measurement of lunar topography. In 1834 Johann Heinrich von Mädler published the first large cartograph (map) of the Moon, comprising 4 sheets, and he subsequently published The Universal Selenography.[3] All lunar measurement was based on direct observation until March 1840, when J.W. Draper, using a 5-inch reflector, produced a daguerreotype of the Moon and thus introduced photography to astronomy. At first, the images were of very poor quality, but as with the telescope 200 years earlier, their quality rapidly improved. By 1890 lunar photography had become a recognized subdiscipline of astronomy.

Lunar photography

The 20th century witnessed more advances in selenography. In 1959, the

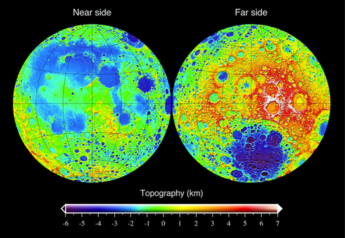

Lunar topography

The Moon has been measured by the methods of

Another distinguishing feature of the Moon's shape is that the elevations are on average about 1.9

Lunar cartography and toponymy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

The oldest known illustration of the Moon was found in a

Denominations of the surface features of the Moon, based on telescopic observation, were made by

In 1647,

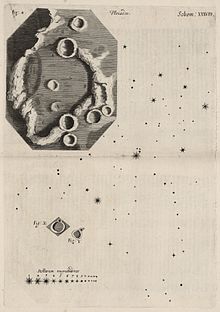

The lunar illustrations in the Almagestum novum were drawn by a fellow

The

Many of the craters were denominated topically pursuant to the octant in which they were located. Craters in Octants I, II, and III were primarily denominated based on names from

The lunar nomenclature of

Later astronomers and lunar cartographers augmented the nomenclature with additional

The IAU later expanded and updated the lunar nomenclature in the 1960s, but new toponyms were limited to toponyms honoring deceased scientists. After

Satellite craters

The assignment of the letters to satellite craters was originally somewhat haphazard. Letters were typically assigned to craters in order of significance rather than location. Precedence depended on the angle of illumination from the

Over time, lunar observers assigned many of the satellite craters an eponym. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) assumed authority to denominate lunar features in 1919. The commission for denominating these features formally adopted the convention of using capital Roman letters to identify craters and valleys.

When suitable cartographs (maps) of the far side of the Moon became available by 1966, Ewen A. Whitaker denominated satellite features based on the angle of their location relative to the major crater with which they were associated. A satellite crater located due north of the major crater was identified as "Z". The full 360° circle around the major crater was then subdivided evenly into 24 parts, like a 24-hour clock. Each "hour" angle, running clockwise, was assigned a letter, beginning with "A" at 1 o'clock. The letters "I" and "O" were omitted, resulting in only 24 letters. Thus a crater due south of its major crater was identified as "M".

Reference elevation

The Moon obviously lacks any

Historical lunar maps

The following historically notable lunar maps and atlases are arranged in chronological order by publication date.

- Michael van Langren, engraved map, 1645.

- Selenographia, 1647.

- Almagestum novum, 1651.

- Giovanni Domenico Cassini, engraved map, 1679 (reprinted in 1787).

- Tobias Mayer, engraved map, 1749, published in 1775.

- Johann Hieronymus Schröter, Selenotopografisches Fragmenten, 1st volume 1791, 2nd volume 1802.

- John Russell, engraved images, 1805.

- Wilhelm Lohrmann, Topographie der sichtbaren Mondoberflaeche, Leipzig, 1824.

- Johann Heinrich Mädler, Mappa Selenographica totam Lunae hemisphaeram visibilem complectens, Berlin, 1834-36.

- Edmund Neison, The Moon, London, 1876.

- Julius Schmidt, Charte der Gebirge des Mondes, Berlin, 1878.

- Thomas Gwyn Elger, The Moon, London, 1895.

- Johann Krieger, Mond-Atlas, 1898. Two additional volumes were published posthumously in 1912 by the Vienna Academy of Sciences.

- Walter Goodacre, Map of the Moon, London, 1910.

- Mary A. Blagg and Karl Müller, Named Lunar Formations, 2 volumes, London, 1935.

- Philipp Fauth, Unser Mond, Bremen, 1936.

- Hugh P. Wilkins, 300-inch Moon map, 1951.

- Gerard Kuiperet al., Photographic Lunar Atlas, Chicago, 1960.

- Ewen A. Whitakeret al., Rectified Lunar Atlas, Tucson, 1963.

- Hermann Fauth and Philipp Fauth (posthumously), Mondatlas, 1964.

- Gerard Kuiperet al., System of Lunar Craters, 1966.

- Yu I. Efremov et al., Atlas Obratnoi Storony Luny, Moscow, 1967–1975.

- NASA, Lunar Topographic Orthophotomaps, 1978.

- Antonín Rükl, Atlas of the Moon, 2004.

Galleries

See also

- Gravitation of the Moon

- Google Moon

- Lunar grazing occultation

- Planetary nomenclature

- Selenographic coordinates

- List of maria on the Moon

- List of craters on the Moon

- List of mountains on the Moon

- List of valleys on the Moon

References

Citations

- ^ Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (2005). "selenodesy" (Selenodesy is "that branch of applied mathematics that determines, by observation and measurement, the exact positions of points and the figures and areas of large portions of the moon's surface, or the shape and size of the moon".). US Department of Defense and The free dictionary (online). Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ Neison, Edmund; Nevill, Edmund Neville (1876). The Moon and the Condition and Configurations of Its Surface. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 81.

democritus moon valleys and mountains.

- ^ Wax and the Honey Moon Archived 2007-07-24 at the Wayback Machine: an account of Maedler's work and the creation of the first wax model of the Moon.

- .

- S2CID 120584696.

- ISBN 0-521-54205-7.

- USGS.

- ISSN 2169-9097.

Bibliography

- Scott L. Montgomery (1999). The Moon and Western Imagination. ISBN 0-8165-1711-8.

- Ewen A. Whitaker (1999). Mapping and Naming the Moon: A History of Lunar Cartography and Nomenclature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62248-4.

- William P. Sheehan; Thomas A. Dobbins (2001). Epic Moon: A history of lunar exploration in the age of the telescope. Willmann-Bell.

External links

- NASA Catalogue of Lunar Nomenclature (1982), Leif E. Andersson and Ewen A. Whitaker

- The Galileo Project: The Moon

- Observing the Moon: The Modern Astronomer's Guide

- Lunar control networks (USGS)

- The Rise And Fall of Lunar Observing Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine, Kevin S. Jung

- Consolidated Lunar Atlas

- Virtual exhibition about the topography of the Moon on the digital library of Paris Observatory