Self-organization

| Complex systems |

|---|

| Topics |

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spontaneous when sufficient energy is available, not needing control by any external agent. It is often triggered by seemingly random fluctuations, amplified by positive feedback. The resulting organization is wholly decentralized, distributed over all the components of the system. As such, the organization is typically robust and able to survive or self-repair substantial perturbation. Chaos theory discusses self-organization in terms of islands of predictability in a sea of chaotic unpredictability.

Self-organization occurs in many

Overview

Self-organization is realized

Self-organization relies on four basic ingredients:[6]

- strong dynamical non-linearity, often (though not necessarily) involving positive and negative feedback

- balance of exploitation and exploration

- multiple interactions among components

- availability of energy (to overcome the natural tendency toward entropy, or loss of free energy)

Principles

The cybernetician

The cybernetician Heinz von Foerster formulated the principle of "order from noise" in 1960.[9] It notes that self-organization is facilitated by random perturbations ("noise") that let the system explore a variety of states in its state space. This increases the chance that the system will arrive into the basin of a "strong" or "deep" attractor, from which it then quickly enters the attractor itself. The biophysicist Henri Atlan developed this concept by proposing the principle of "complexity from noise"[10][11] (French: le principe de complexité par le bruit)[12] first in the 1972 book L'organisation biologique et la théorie de l'information and then in the 1979 book Entre le cristal et la fumée. The physicist and chemist Ilya Prigogine formulated a similar principle as "order through fluctuations"[13] or "order out of chaos".[14] It is applied in the method of simulated annealing for problem solving and machine learning.[15]

History

The idea that the

The philosopher

Immanuel Kant used the term "self-organizing" in his 1790 Critique of Judgment, where he argued that teleology is a meaningful concept only if there exists such an entity whose parts or "organs" are simultaneously ends and means. Such a system of organs must be able to behave as if it has a mind of its own, that is, it is capable of governing itself.[17]

In such a natural product as this every part is thought as owing its presence to the agency of all the remaining parts, and also as existing for the sake of the others and of the whole, that is as an instrument, or organ... The part must be an organ producing the other parts—each, consequently, reciprocally producing the others... Only under these conditions and upon these terms can such a product be an organized and self-organized being, and, as such, be called a physical end.[17]

Sadi Carnot (1796–1832) and Rudolf Clausius (1822–1888) discovered the second law of thermodynamics in the 19th century. It states that total entropy, sometimes understood as disorder, will always increase over time in an isolated system. This means that a system cannot spontaneously increase its order without an external relationship that decreases order elsewhere in the system (e.g. through consuming the low-entropy energy of a battery and diffusing high-entropy heat).[18][19]

18th-century thinkers had sought to understand the "universal laws of form" to explain the observed forms of living organisms. This idea became associated with Lamarckism and fell into disrepute until the early 20th century, when D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860–1948) attempted to revive it.[20]

The psychiatrist and engineer

Self-organization was associated[

Around 2008–2009, a concept of guided self-organization started to take shape. This approach aims to regulate self-organization for specific purposes, so that a dynamical system may reach specific attractors or outcomes. The regulation constrains a self-organizing process within a complex system by restricting local interactions between the system components, rather than following an explicit control mechanism or a global design blueprint. The desired outcomes, such as increases in the resultant internal structure and/or functionality, are achieved by combining task-independent global objectives with task-dependent constraints on local interactions.[23][24]

By field

Physics

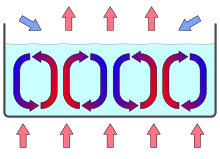

The many self-organizing phenomena in

Chemistry

Self-organization in

Biology

Self-organization in biology[37] can be observed in spontaneous folding of proteins and other biomacromolecules, self-assembly of lipid bilayer membranes, pattern formation and morphogenesis in developmental biology, the coordination of human movement, eusocial behaviour in insects (bees, ants, termites)[38] and mammals, and flocking behaviour in birds and fish.[39]

The mathematical biologist

The evolution of order in living systems and the generation of order in certain non-living systems was proposed to obey a common fundamental principal called “the Darwinian dynamic”[43] that was formulated by first considering how microscopic order is generated in simple non-biological systems that are far from thermodynamic equilibrium. Consideration was then extended to short, replicating RNA molecules assumed to be similar to the earliest forms of life in the RNA world. It was shown that the underlying order-generating processes of self-organization in the non-biological systems and in replicating RNA are basically similar.

Cosmology

In his 1995 conference paper "Cosmology as a problem in critical phenomena"

Computer science

Phenomena from

Cybernetics

In the 1970s Stafford Beer considered self-organization necessary for autonomy in persisting and living systems. He applied his viable system model to management. It consists of five parts: the monitoring of performance of the survival processes (1), their management by recursive application of regulation (2), homeostatic operational control (3) and development (4) which produce maintenance of identity (5) under environmental perturbation. Focus is prioritized by an alerting "algedonic loop" feedback: a sensitivity to both pain and pleasure produced from under-performance or over-performance relative to a standard capability.[62]

In the 1990s Gordon Pask argued that von Foerster's H and Hmax were not independent, but interacted via countably infinite recursive concurrent spin processes[63] which he called concepts. His strict definition of concept "a procedure to bring about a relation"[64] permitted his theorem "Like concepts repel, unlike concepts attract"[65] to state a general spin-based principle of self-organization. His edict, an exclusion principle, "There are No Doppelgangers" means no two concepts can be the same. After sufficient time, all concepts attract and coalesce as pink noise. The theory applies to all organizationally closed or homeostatic processes that produce enduring and coherent products which evolve, learn and adapt.[66][63]

Sociology

The self-organizing behaviour of social animals and the self-organization of simple mathematical structures both suggest that self-organization should be expected in human

In social theory, the concept of self-referentiality has been introduced as a sociological application of self-organization theory by Niklas Luhmann (1984). For Luhmann the elements of a social system are self-producing communications, i.e. a communication produces further communications and hence a social system can reproduce itself as long as there is dynamic communication. For Luhmann, human beings are sensors in the environment of the system. Luhmann developed an evolutionary theory of society and its subsystems, using functional analyses and systems theory.[69]

Economics

The

Learning

Enabling others to "learn how to learn"[74] is often taken to mean instructing them[75] how to submit to being taught. Self-organised learning (SOL)[76][77][78] denies that "the expert knows best" or that there is ever "the one best method",[79][80][81] insisting instead on "the construction of personally significant, relevant and viable meaning"[82] to be tested experientially by the learner.[83] This may be collaborative, and more rewarding personally.[84][85] It is seen as a lifelong process, not limited to specific learning environments (home, school, university) or under the control of authorities such as parents and professors.[86] It needs to be tested, and intermittently revised, through the personal experience of the learner.[87] It need not be restricted by either consciousness or language.[88] Fritjof Capra argued that it is poorly recognised within psychology and education.[89] It may be related to cybernetics as it involves a negative feedback control loop,[64] or to systems theory.[90] It can be conducted as a learning conversation or dialogue between learners or within one person.[91][92]

Transportation

The self-organizing behavior of drivers in traffic flow determines almost all the spatiotemporal behavior of traffic, such as traffic breakdown at a highway bottleneck, highway capacity, and the emergence of moving traffic jams. These self-organizing effects are explained by Boris Kerner's three-phase traffic theory.[93]

Linguistics

Order appears spontaneously in the

Research

Self-organized funding allocation (SOFA) is a method of distributing funding for scientific research. In this system, each researcher is allocated an equal amount of funding, and is required to anonymously allocate a fraction of their funds to the research of others. Proponents of SOFA argue that it would result in similar distribution of funding as the present grant system, but with less overhead.[95] In 2016, a test pilot of SOFA began in the Netherlands.[96]

Criticism

Heinz Pagels, in a 1985 review of Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers's book Order Out of Chaos in Physics Today, appeals to authority:[97]

Most scientists would agree with the critical view expressed in Problems of Biological Physics (Springer Verlag, 1981) by the biophysicist L. A. Blumenfeld, when he wrote: "The meaningful macroscopic ordering of biological structure does not arise due to the increase of certain parameters or a system above their critical values. These structures are built according to program-like complicated architectural structures, the meaningful information created during many billions of years of chemical and biological evolution being used." Life is a consequence of microscopic, not macroscopic, organization.

Of course, Blumenfeld does not answer the further question of how those program-like structures emerge in the first place. His explanation leads directly to infinite regress.

In short, they [Prigogine and Stengers] maintain that time irreversibility is not derived from a time-independent microworld, but is itself fundamental. The virtue of their idea is that it resolves what they perceive as a "clash of doctrines" about the nature of time in physics. Most physicists would agree that there is neither empirical evidence to support their view, nor is there a mathematical necessity for it. There is no "clash of doctrines." Only Prigogine and a few colleagues hold to these speculations which, in spite of their efforts, continue to live in the twilight zone of scientific credibility.

In theology, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) in his Summa Theologica assumes a teleological created universe in rejecting the idea that something can be a self-sufficient cause of its own organization:[98]

Since nature works for a determinate end under the direction of a higher agent, whatever is done by nature must needs be traced back to God, as to its first cause. So also whatever is done voluntarily must also be traced back to some higher cause other than human reason or will, since these can change or fail; for all things that are changeable and capable of defect must be traced back to an immovable and self-necessary first principle, as was shown in the body of the Article.

See also

- Autopoiesis

- Autowave

- Self-organized criticality control

- Free energy principle

- Information theory

- Constructal law

- Swarm intelligence

- Practopoiesis

- Outline of organizational theory

Notes

- ^ For related history, see Aram Vartanian, Diderot and Descartes.

References

- .

- ISBN 0-471-30280-5

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-11624-2. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-238-183-5.

We have already seen ample evidence for what is arguably the single most impressive general property of CA, namely their capacity for self-organization

- ISBN 978-1-4020-3916-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-513159-8.

- ^ PMID 20270223.

- ^ Ashby, W. R. (1962). "Principles of the self-organizing system", pp. 255–78 in Principles of Self-Organization. Heinz von Foerster and George W. Zopf, Jr. (eds.) U.S. Office of Naval Research.

- ^ Von Foerster, H. (1960). "On self-organizing systems and their environments", pp. 31–50 in Self-organizing systems. M.C. Yovits and S. Cameron (eds.), Pergamon Press, London

- ^ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ISBN 978-3-11-096801-9.

- ^ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ^ Nicolis, G. and Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-organization in nonequilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations. Wiley, New York.

- ^ Prigogine, I. and Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man's new dialogue with nature. Bantam Books.

- S2CID 10126852.

- ISBN 978-0-674-72557-7.

Ada Palmer explores how Renaissance readers, such as Machiavelli, Pomponio Leto, and Montaigne, actually ingested and disseminated Lucretius, ... and shows how ideas of emergent order and natural selection, so critical to our current thinking, became embedded in Europe's intellectual landscape before the seventeenth century.

- ^ a b German Aesthetic. CUP Archive. pp. 64–. GGKEY:TFTHBB91ZH2.

- ISBN 0-7190-1741-6

- . Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7391-7437-1.

- ^ Asaro, P. (2007). "Heinz von Foerster and the Bio-Computing Movements of the 1960s" in Albert Müller and Karl H. Müller (eds.) An Unfinished Revolution? Heinz von Foerster and the Biological Computer Laboratory BCL 1958–1976. Vienna, Austria: Edition Echoraum.

- ^

As an indication of the increasing importance of this concept, when queried with the keyword

self-organ*, Dissertation Abstracts finds nothing before 1954, and only four entries before 1970. There were 17 in the years 1971–1980; 126 in 1981–1990; and 593 in 1991–2000. - ^ Phys.org, Self-organizing robots: Robotic construction crew needs no foreman (w/ video), February 13, 2014.

- ^ Science Daily, Robotic systems: How sensorimotor intelligence may develop... self-organized behaviors , October 27, 2015.

- Zeiger, H. J.and Kelley, P. L. (1991) "Lasers", pp. 614–19 in The Encyclopedia of Physics, Second Edition, edited by Lerner, R. and Trigg, G., VCH Publishers.

- ^ Ansari M. H. (2004) Self-organized theory in quantum gravity. arxiv.org

- ^ Lozeanu, Erzilia; Popescu, Virginia; Sanduloviciu, Mircea (February 2002). "Spatial and spatiotemporal patterns formed after self-organization in plasma". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 30 (1): 30–31. .

- S2CID 233702358.

- PMID 15024422.

- S2CID 96957407.

- .

- .

- S2CID 95102727. Archived from the original(PDF) on October 8, 2012.

- PMID 15826011.

- .

- PMID 27671093.

- ISBN 0-691-11624-5

- PMID 21238030.

- ISBN 978-0-12-004532-7. Archived from the original(PDF) on December 20, 2016.

- PMC 1226010.

- ^ Goodwin, Brian (2009). "Beyond the Darwinian Paradigm: Understanding Biological Forms". In Ruse, Michael; Travis, Joseph (eds.). Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- S2CID 10903076.

- ^ Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RA, Vemulapalli GK. (1983) The Darwinian Dynamic. Quarterly Review of Biology 58, 185-207. JSTOR 2828805

- .

- S2CID 41179835.

- S2CID 1937763.

- ^ X. S. Yang (2014) Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms, Elsevier.

- S2CID 4429113.

- .

- S2CID 9155618.

- hdl:20.500.12749/3552.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ].

- ISBN 978-989-758-182-3.

- ^ Wiener, Norbert (1962) "The mathematics of self-organising systems". Recent developments in information and decision processes, Macmillan, N. Y. and Chapter X in Cybernetics, or control and communication in the animal and the machine, The MIT Press.

- ^ Cybernetics, or control and communication in the animal and the machine, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and Wiley, NY, 1948. 2nd Edition 1962 "Chapter X "Brain Waves and Self-Organizing Systems" pp. 201–02.

- Ashby, William Ross(1952) Design for a Brain, Chapter 5 Chapman & Hall

- ^ Ashby, William Ross (1956) An Introduction to Cybernetics, Part Two Chapman & Hall

- .

- ^ Embodiments of Mind MIT Press (1965)"

- ^ von Foerster, Heinz; Pask, Gordon (1961). "A Predictive Model for Self-Organizing Systems, Part I". Cybernetica. 3: 258–300.

- ^ von Foerster, Heinz; Pask, Gordon (1961). "A Predictive Model for Self-Organizing Systems, Part II". Cybernetica. 4: 20–55.

- ^ "Brain of the Firm" Alan Lane (1972); see also Viable System Model in "Beyond Dispute", and Stafford Beer (1994) "Redundancy of Potential Command" pp. 157–58.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Pask, G. (1973). Conversation, Cognition and Learning. A Cybernetic Theory and Methodology. Elsevier

- .

- ^ Pask, Gordon (1993) Interactions of Actors (IA), Theory and Some Applications.

- ^ Interactive models for self organization and biological systems Center for Models of Life, Niels Bohr Institute, Denmark

- JSTOR 201903– via JSTOR.

- ISBN 0-8047-2625-6

- ISBN 1-55786-699-6

- ^ Hayek, F. (1976) Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 2: The Mirage of Social Justice. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Biel, R.; Mu-Jeong Kho (November 2009). "The Issue of Energy within a Dialectical Approach to the Regulationist Problematique" (PDF). Recherches & Régulation Working Papers, RR Série ID 2009-1. Association Recherche & Régulation: 1–21. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ISBN 1-86094-330-6

- ^ Rogers.C. (1969). Freedom to Learn. Merrill

- ISBN 978-0-521-65862-1

- ^ Thomas L.F. & Augstein E.S. (1985) Self-Organised Learning: Foundations of a conversational science for psychology. Routledge (1st Ed.)

- ^ Thomas L.F. & Augstein E.S. (1994) Self-Organised Learning: Foundations of a conversational science for psychology. Routledge (2nd Ed.)

- ^ Thomas L.F. & Augstein E.S. (2013) Learning: Foundations of a conversational science for psychology. Routledge (Psy. Revivals)

- ^ Harri-Augstein E. S. and Thomas L. F. (1991) Learning Conversations: The S-O-L way to personal and organizational growth. Routledge (1st Ed.)

- ^ Harri-Augstein E. S. and Thomas L. F. (2013) Learning Conversations: The S-O-L way to personal and organizational growth. Routledge (2nd Ed.)

- ^ Harri-Augstein E. S. and Thomas L. F. (2013)Learning Conversations: The S-O-L way to personal and organizational growth. BookBaby (eBook)

- ^ Illich. I. (1971) A Celebration of Awareness. Penguin Books.

- ^ Harri-Augstein E. S. (2000) The University of Learning in transformation

- ISBN 1-870098-66-8

- ^ Revans R. W. (1982) The Origins and Growth of Action Learning Chartwell-Bratt, Bromley

- ^ Thomas L.F. and Harri-Augstein S. (1993) "On Becoming a Learning Organisation" in Report of a 7 year Action Research Project with the Royal Mail Business. CSHL Monograph

- ^ Rogers C.R. (1971) On Becoming a Person. Constable, London

- ^ Prigogyne I. & Sengers I. (1985) Order out of Chaos Flamingo Paperbacks. London

- ^ Capra F (1989) Uncommon Wisdom Flamingo Paperbacks. London

- ^ Bohm D. (1994) Thought as a System. Routledge.

- ^ Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak-experiences, Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- ^ Conversational Science Thomas L.F. and Harri-Augstein E.S. (1985)

- .

- ^ De Boer, Bart (2011). Gibson, Kathleen R.; Tallerman, Maggie (eds.). Self-organization and language evolution. Oxford.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - PMID 30089925.

- ^ Coelho, Andre (May 16, 2017). "Netherlands: A radical new way do fund science | BIEN". Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- .

- ^ Article 3. Whether God exists? newadvent.org

Further reading

- W. Ross Ashby (1966), Design for a Brain, Chapman & Hall, 2nd edition.

- Per Bak (1996), How Nature Works: The Science of Self-Organized Criticality, Copernicus Books.

- Philip Ball (1999), The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature, Oxford University Press.

- Stafford Beer, Self-organization as autonomy: Brain of the Firm 2nd edition Wiley 1981 and Beyond Dispute Wiley 1994.

- Adrian Bejan (2000), Shape and Structure, from Engineering to Nature, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 324 pp.

- Mark Buchanan (2002), Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Theory of Networks W. W. Norton & Company.

- Scott Camazine, Jean-Louis Deneubourg, Nigel R. Franks, James Sneyd, Guy Theraulaz, & Eric Bonabeau (2001) Self-Organization in Biological Systems, Princeton Univ Press.

- Falko Dressler (2007), Self-Organization in Sensor and Actor Networks, Wiley & Sons.

- Manfred Eigen and Peter Schuster (1979), The Hypercycle: A principle of natural self-organization, Springer.

- Myrna Estep (2003), A Theory of Immediate Awareness: Self-Organization and Adaptation in Natural Intelligence, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Myrna L. Estep (2006), Self-Organizing Natural Intelligence: Issues of Knowing, Meaning, and Complexity, Springer-Verlag.

- J. Doyne Farmer et al. (editors) (1986), "Evolution, Games, and Learning: Models for Adaptation in Machines and Nature", in: Physica D, Vol 22.

- Carlos Gershenson and Francis Heylighen (2003). "When Can we Call a System Self-organizing?" In Banzhaf, W, T. Christaller, P. Dittrich, J. T. Kim, and J. Ziegler, Advances in Artificial Life, 7th European Conference, ECAL 2003, Dortmund, Germany, pp. 606–14. LNAI 2801. Springer.

- Hermann Haken (1983) Synergetics: An Introduction. Nonequilibrium Phase Transition and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry, and Biology, Third Revised and Enlarged Edition, Springer-Verlag.

- F.A. HayekLaw, Legislation and Liberty, RKP, UK.

- Francis Heylighen (2001): "The Science of Self-organization and Adaptivity".

- Arthur Iberall (2016), Homeokinetics: The Basics, Strong Voices Publishing, Medfield, Massachusetts.

- Henrik Jeldtoft Jensen (1998), Self-Organized Criticality: Emergent Complex Behaviour in Physical and Biological Systems, Cambridge Lecture Notes in Physics 10, Cambridge University Press.

- Steven Berlin Johnson (2001), Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software.

- Stuart Kauffman (1995), At Home in the Universe, Oxford University Press.

- Stuart Kauffman (1993), Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution Oxford University Press.

- J. A. Scott Kelso (1995), Dynamic Patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- J. A. Scott Kelso & David A Engstrom (2006), "The Complementary Nature", The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Alex Kentsis (2004), Self-organization of biological systems: Protein folding and supramolecular assembly, Ph.D. Thesis, New York University.

- E.V. Krishnamurthy (2009)", Multiset of Agents in a Network for Simulation of Complex Systems", in "Recent advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and synchronization, (NDS-1) – Theory and applications, Springer Verlag, New York, 2009. Eds. K.Kyamakya, et al.

- Paul Krugman (1996), The Self-Organizing Economy, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Elizabeth McMillan (2004) "Complexity, Organizations and Change".

- Marshall, A (2002) The Unity of Nature, Imperial College Press: London (esp. chapter 5)

- Müller, J.-A., Lemke, F. (2000), Self-Organizing Data Mining.

- Gregoire Nicolis and Ilya Prigogine (1977) Self-Organization in Non-Equilibrium Systems, Wiley.

- Heinz Pagels (1988), The Dreams of Reason: The Computer and the Rise of the Sciences of Complexity, Simon & Schuster.

- Gordon Pask (1961), The cybernetics of evolutionary processes and of self organizing systems, 3rd. International Congress on Cybernetics, Namur, Association Internationale de Cybernetique.

- Christian Prehofer ea. (2005), "Self-Organization in Communication Networks: Principles and Design Paradigms", in: IEEECommunications Magazine, July 2005.

- Mitchell Resnick (1994), Turtles, Termites and Traffic Jams: Explorations in Massively Parallel Microworlds, Complex Adaptive Systems series, MIT Press.[ISBN missing]

- Lee Smolin (1997), The Life of the Cosmos Oxford University Press.

- Ricard V. Solé and Brian C. Goodwin (2001), Signs of Life: How Complexity Pervades Biology], Basic Books.

- Ricard V. Solé and Jordi Bascompte (2006), in Complex Ecosystems, Princeton U. Press

- S2CID 19333503.

- Steven Strogatz (2004), Sync: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order, Thesis.

- D'Arcy Thompson(1917), On Growth and Form, Cambridge University Press, 1992 Dover Publications edition.

- J. Tkac, J Kroc (2017), Cellular Automaton Simulation of Dynamic Recrystallization: Introduction into Self-Organization and Emergence "(open source software)" "Video – Simulation of DRX"

- Tom De Wolf, Tom Holvoet (2005), Emergence Versus Self-Organisation: Different Concepts but Promising When Combined, In Engineering Self Organising Systems: Methodologies and Applications, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, volume 3464, pp. 1–15.

- K. Yee (2003), "Ownership and Trade from Evolutionary Games", International Review of Law and Economics, 23.2, 183–197.

- Louise B. Young (2002), The Unfinished Universe[ISBN missing]

External links

- Hermann Haken (ed.). "Self-organization". Scholarpedia.

- Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization, Göttingen

- PDF file on self-organized common law with references

- An entry on self-organization at the Principia Cybernetica site

- The Science of Self-organization and Adaptivity, a review paper by Francis Heylighen

- The Self-Organizing Systems (SOS) FAQ by Chris Lucas, from the USENET newsgroup

comp.theory.self-org.sys - David Griffeath, Primordial Soup Kitchen (graphics, papers)

- nlin.AO, nonlinear preprint archive, (electronic preprints in adaptation and self-organizing systems)

- Structure and Dynamics of Organic Nanostructures Archived April 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Metal organic coordination networks of oligopyridines and Cu on graphite Archived June 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Selforganization in complex networks The Complex Systems Lab, Barcelona

- Computational Mechanics Group at the Santa Fe Institute

- "Organisation must grow" (1939) W. Ross Ashby journal p. 759, from The W. Ross Ashby Digital Archive

- Cosma Shalizi's notebook on self-organization from 2003-06-20, used under the GFDL with permission from author.

- Connectivism:SelfOrganization

- UCLA Human Complex Systems Program

- "Interactions of Actors (IA), Theory and Some Applications" 1993 Gordon Pask's theory of learning, evolution and self-organization (in draft).

- The Cybernetics Society

- Scott Camazine's webpage on self-organization in biological systems

- Mikhail Prokopenko's page on Information-driven Self-organisation (IDSO)

- Lakeside Labs Self-Organizing Networked Systems A platform for science and technology, Klagenfurt, Austria.

- Watch 32 discordant metronomes synch up all by themselves theatlantic.com