Self-reference

Self-reference is a concept that involves referring to oneself or one's own attributes, characteristics, or actions. It can occur in language, logic, mathematics, philosophy, and other fields.

In natural or formal languages, self-reference occurs when a sentence, idea or formula refers to itself. The reference may be expressed either directly—through some intermediate sentence or formula—or by means of some encoding.

In philosophy, self-reference also refers to the ability of a subject to speak of or refer to itself, that is, to have the kind of thought expressed by the first person nominative singular pronoun "I" in English.

Self-reference is studied and has applications in mathematics, philosophy, computer programming, second-order cybernetics, and linguistics, as well as in humor. Self-referential statements are sometimes paradoxical, and can also be considered recursive.

In logic, mathematics and computing

In classical

In

In game theory, undefined behaviors can occur where two players must model each other's mental states and behaviors, leading to infinite regress.

In

Tupper's self-referential formula is a mathematical curiosity which plots an image of its own formula.

In biology

The biology of self-replication is self-referential, as embodied by DNA and RNA replication mechanisms. Models of self-replication are found in Conway's Game of Life and have inspired engineering systems such as the self-replicating 3D printer RepRap.[citation needed]

In art

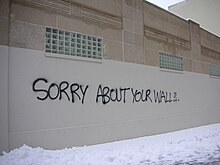

Self-reference occurs in

Self-reference in art is closely related to the concepts of breaking the fourth wall and meta-reference, which often involve self-reference. The short stories of Jorge Luis Borges play with self-reference and related paradoxes in many ways. Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape consists entirely of the protagonist listening to and making recordings of himself, mostly about other recordings. During the 1990s and 2000s filmic self-reference was a popular part of the rubber reality movement, notably in Charlie Kaufman's films Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, the latter pushing the concept arguably to its breaking point as it attempts to portray its own creation, in a dramatized version of the Droste effect.

Various

The Quran includes numerous instances of self-referentiality.[6][7]

The

In language

A word that describes itself is called an

A sentence which inventories its own letters and punctuation marks is called an autogram.

There is a special case of meta-sentence in which the content of the sentence in the metalanguage and the content of the sentence in the object language are the same. Such a sentence is referring to itself. However some meta-sentences of this type can lead to paradoxes. "This is a sentence." can be considered to be a self-referential meta-sentence which is obviously true. However "This sentence is false" is a meta-sentence which leads to a self-referential

Self-reference occasionally occurs in the

Fumblerules are a list of rules of good grammar and writing, demonstrated through sentences that violate those very rules, such as "Avoid cliches like the plague" and "Don't use no double negatives". The term was coined in a published list of such rules by William Safire.[9][10]

The adverb "hereby" is used in a self-referential way, for example in the statement "I hereby declare you husband and wife."[12]

In popular culture

- Douglas Hofstadter's books, especially Metamagical Themas and Gödel, Escher, Bach, play with many self-referential concepts and were highly influential in bringing them into mainstream intellectual culture during the 1980s. Hofstadter's law, which specifies that "It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law"[13] is an example of a self-referencing adage. Hofstadter also suggested the concept of a 'Reviews of this book', a book containing only reviews of itself, which has since been implemented using wikis and other technologies. Hofstadter's 'strange loop' metaphysics attempts to map consciousness onto self-reference, but is a minority position in philosophy of mind.

- The subgenre of "science-fiction fandom, some about science fiction and its authors.[14]

In law

Several constitutions contain self-referential clauses defining how the constitution itself may be amended.

See also

- Circular reference – Series of references where the last object references the first

- Droste effect – Recursive visual effect

- Mise en abyme – Technique of placing a copy of an image within itself, or a story within a story

- Fourth wall – Concept in performing arts separating performers from the audience

- List of self–referential paradoxes– List of statements that appear to contradict themselves

- Meta-joke– Humor that alludes to itself

- Recursion – Process of repeating items in a self-similar way

- Recursive acronym – Acronym whose expansion includes a copy of itself

- Quine (computing) – Self-replicating program

- Strange loop – Cyclic structure that goes through several levels in a hierarchical system

- this (computer programming) – In programming languages, the object or class the currently running code belongs to

- Bilingual tautological expressions – Redundancy in linguistic expression

- Lucid dreaming– Dream where one is aware that one is dreaming – A dream during which the dreamer is aware that they are dreaming

- Use–mention distinction

References

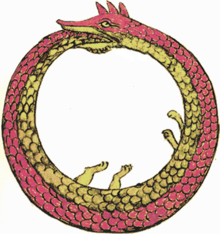

- ^ Soto-Andrade, Jorge; Jaramillo, Sebastian; Gutierrez, Claudio; Letelier, Juan-Carlos. "Ouroboros avatars: A mathematical exploration of Self-reference and Metabolic Closure" (PDF). MIT Press. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Liar Paradox. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2020.

- ^ Malenfant, J.; Demers, F-N. "A Tutorial on Behavioral Reflection and its Implementation" (PDF). PARC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8176-4768-1.

- ISBN 1-101-15281-8.

- ^ Madigan, David. The Qur'ân's Self-Image. Writing and Authority in Islam's Scripture.

- ^ Boisliveau, Anne-Sylvie. Le Coran par lui-même.

- ISBN 978-3-11-019464-7.

- ^ "alt.usage.english.org's Humorous Rules for Writing".

- ^ Safire, William (4 November 1979). "On Language; The Fumblerules of Grammar". The New York Times (published 4 November 1979). p. SM4.

- ISBN 978-0-313-27596-8.

- ^ "hereby in wiktionary". 19 June 2023.

- ISBN 0-465-02656-7

- ^ "Recursive Science Fiction, updated 3 August 2008". New England Science Fiction Association.

- ISBN 978-0-19-825388-4.

Sources

- Bartlett, Steven J. [James] (Ed.) (1992). Reflexivity: A Source-book in Self-reference. Amsterdam, North-Holland. (PDF). RePub, Erasmus University

- Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. New York, Vintage Books.

- ISBN 0-19-853450-7

- Crabtree, Jonathan J. (2016), The Lost Logic of Elementary Mathematics and the Haberdasher who Kidnapped Kaizen, Proceedings of the Mathematical Association of Victoria (MAV) Annual Conference, 53, 98–106, ISBN 978-1-876949-60-0