Self-replication

Self-replication is any behavior of a

Overview

Theory

Early research by John von Neumann[2] established that replicators have several parts:

- A coded representation of the replicator

- A mechanism to copy the coded representation

- A mechanism for effecting construction within the host environment of the replicator

Exceptions to this pattern may be possible, although almost all known examples adhere to it. Scientists have come close to constructing RNA that can be copied in an "environment" that is a solution of RNA monomers and transcriptase, but such systems are more accurately characterized as "assisted replication" than "self-replication". In 2021 researchers succeeded in constructing a system with sixteen specially designed DNA sequences. Four of these can be linked together (through base pairing) in a certain order following a template of four already-linked sequences, by changing the temperature up and down. The number of template copies is thus increased in each cycle. No external agent such as an enzyme is needed, but the system must be supplied with a reservoir of the sixteen DNA sequences.[3]

The simplest possible case is that only a genome exists. Without some specification of the self-reproducing steps, a genome-only system is probably better characterized as something like a crystal.

Origin of life

Self-replication is a fundamental feature of life. It was proposed that self-replication emerged in the evolution of life when a molecule similar to a double-stranded polynucleotide (possibly like RNA) dissociated into single-stranded polynucleotides and each of these acted as a template for synthesis of a complementary strand producing two double stranded copies.[4] In a system such as this, individual duplex replicators with different nucleotide sequences could compete with each other for available mononucleotide resources, thus initiating natural selection for the most “fit” sequences.[4] Replication of these early forms of life was likely highly inaccurate producing mutations that influenced the folding state of the polynucleotides, thus affecting the propensities for strand association (promoting stability) and disassociation (allowing genome replication). The evolution of order in living systems has been proposed to be an example of a fundamental order generating principle that also applies to physical systems.[5]

Classes of self-replication

Recent research[6] has begun to categorize replicators, often based on the amount of support they require.

- Natural replicators have all or most of their design from nonhuman sources. Such systems include natural life forms.

- Autotrophic replicators can reproduce themselves "in the wild". They mine their own materials. It is conjectured that non-biological autotrophic replicators could be designed by humans, and could easily accept specifications for human products.

- Self-reproductive systems are conjectured systems which would produce copies of themselves from industrial feedstocks such as metal bar and wire.

- Self-assembling systems assemble copies of themselves from finished, delivered parts. Simple examples of such systems have been demonstrated at the macro scale.

The design space for machine replicators is very broad. A comprehensive study[7] to date by Robert Freitas and Ralph Merkle has identified 137 design dimensions grouped into a dozen separate categories, including: (1) Replication Control, (2) Replication Information, (3) Replication Substrate, (4) Replicator Structure, (5) Passive Parts, (6) Active Subunits, (7) Replicator Energetics, (8) Replicator Kinematics, (9) Replication Process, (10) Replicator Performance, (11) Product Structure, and (12) Evolvability.

A self-replicating computer program

In computer science a quine is a self-reproducing computer program that, when executed, outputs its own code. For example, a quine in the Python programming language is:

a='a=%r;print(a%%a)';print(a%a)

A more trivial approach is to write a program that will make a copy of any stream of data that it is directed to, and then direct it at itself. In this case the program is treated as both executable code, and as data to be manipulated. This approach is common in most self-replicating systems, including biological life, and is simpler as it does not require the program to contain a complete description of itself.

In many programming languages an empty program is legal, and executes without producing errors or other output. The output is thus the same as the source code, so the program is trivially self-reproducing.

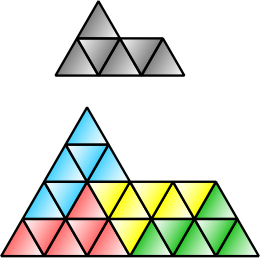

Self-replicating tiling

In

In 2012, Lee Sallows identified rep-tiles as a special instance of a self-tiling tile set or setiset. A setiset of order n is a set of n shapes that can be assembled in n different ways so as to form larger replicas of themselves. Setisets in which every shape is distinct are called 'perfect'. A rep-n rep-tile is just a setiset composed of n identical pieces.

|

Self replicating clay crystals

One form of natural self-replication that is not based on DNA or RNA occurs in clay crystals.[10] Clay consists of a large number of small crystals, and clay is an environment that promotes crystal growth. Crystals consist of a regular lattice of atoms and are able to grow if e.g. placed in a water solution containing the crystal components; automatically arranging atoms at the crystal boundary into the crystalline form. Crystals may have irregularities where the regular atomic structure is broken, and when crystals grow, these irregularities may propagate, creating a form of self-replication of crystal irregularities. Because these irregularities may affect the probability of a crystal breaking apart to form new crystals, crystals with such irregularities could even be considered to undergo evolutionary development.

Applications

It is a long-term goal of some engineering sciences to achieve a

A fully novel artificial replicator is a reasonable near-term goal. A

Given the currently keen interest in biotechnology and the high levels of funding in that field, attempts to exploit the replicative ability of existing cells are timely, and may easily lead to significant insights and advances.

A variation of self replication is of practical relevance in compiler construction, where a similar bootstrapping problem occurs as in natural self replication. A compiler (phenotype) can be applied on the compiler's own source code (genotype) producing the compiler itself. During compiler development, a modified (mutated) source is used to create the next generation of the compiler. This process differs from natural self-replication in that the process is directed by an engineer, not by the subject itself.

Mechanical self-replication

An activity in the field of robots is the self-replication of machines. Since all robots (at least in modern times) have a fair number of the same features, a self-replicating robot (or possibly a hive of robots) would need to do the following:

- Obtain construction materials

- Manufacture new parts including its smallest parts and thinking apparatus

- Provide a consistent power source

- Program the new members

- error correct any mistakes in the offspring

On a

.The Foresight Institute has published guidelines for researchers in mechanical self-replication.[12] The guidelines recommend that researchers use several specific techniques for preventing mechanical replicators from getting out of control, such as using a broadcast architecture.

For a detailed article on mechanical reproduction as it relates to the industrial age see mass production.

Fields

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Research has occurred in the following areas:

- Biology: studies of organismal and cellular natural replication and replicators, and their interaction, including sub-disciplines such as population dynamics, quorum sensing, autophagy pathways. These can be an important guide to avoid design difficulties in self-replicating machinery.

- Chemistry: self-replication studies are typically about how a specific set of molecules can act together to replicate each other within the set[13] (often part of Systems chemistry field).

- Biochemistry: simple systems of in vitro ribosomal self replication have been attempted,[14] but as of January 2021, indefinite in vitro ribosomal self replication has not been achieved in the lab.

- assemblers. Without self-replication, capital and assembly costs of molecular machinesbecome impossibly large. Many bottom-up approaches to nanotechnology take advantage of biochemical or chemical self-assembly.

- Space resources: NASA has sponsored a number of design studies to develop self-replicating mechanisms to mine space resources. Most of these designs include computer-controlled machinery that copies itself.

- Memetics: The idea of a meme was coined by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene where he proposed a cognitive equivalent of the gene; a unit of behavior which is copied from one host mind to another through observation. Memes can only propagate via animal behavior and are thus analogous to information viruses and are often described as viral.

- Computer security: Many computer security problems are caused by self-reproducing computer programs that infect computers — computer worms and computer viruses.

- Parallel computing: loading a new program on every node of a large computer cluster or distributed computing system is time consuming. Using a mobile agents to self-replicate code from node-to-node can save the system administrator a lot of time. Mobile agents have a potential to crash a computer cluster if poorly implemented.

In industry

Space exploration and manufacturing

The goal of self-replication in space systems is to exploit large amounts of matter with a low launch mass. For example, an

In general, since these systems are autotrophic, they are the most difficult and complex known replicators. They are also thought to be the most hazardous, because they do not require any inputs from human beings in order to reproduce.

A classic theoretical study of replicators in space is the 1980 NASA study of autotrophic clanking replicators, edited by Robert Freitas.[15]

Much of the design study was concerned with a simple, flexible chemical system for processing lunar regolith, and the differences between the ratio of elements needed by the replicator, and the ratios available in regolith. The limiting element was Chlorine, an essential element to process regolith for Aluminium. Chlorine is very rare in lunar regolith, and a substantially faster rate of reproduction could be assured by importing modest amounts.

The reference design specified small computer-controlled electric carts running on rails. Each cart could have a simple hand or a small bull-dozer shovel, forming a basic robot.

Power would be provided by a "canopy" of solar cells supported on pillars. The other machinery could run under the canopy.

A "casting robot" would use a robotic arm with a few sculpting tools to make plaster molds. Plaster molds are easy to make, and make precise parts with good surface finishes. The robot would then cast most of the parts either from non-conductive molten rock (basalt) or purified metals. An electric oven melted the materials.

A speculative, more complex "chip factory" was specified to produce the computer and electronic systems, but the designers also said that it might prove practical to ship the chips from Earth as if they were "vitamins".

Molecular manufacturing

These systems are substantially simpler than autotrophic systems, because they are provided with purified feedstocks and energy. They do not have to reproduce them. This distinction is at the root of some of the controversy about whether

Merely exploiting the replicative abilities of existing cells is insufficient, because of limitations in the process of protein biosynthesis (also see the listing for RNA). What is required is the rational design of an entirely novel replicator with a much wider range of synthesis capabilities.

In 2011, New York University scientists have developed artificial structures that can self-replicate, a process that has the potential to yield new types of materials. They have demonstrated that it is possible to replicate not just molecules like cellular DNA or RNA, but discrete structures that could in principle assume many different shapes, have many different functional features, and be associated with many different types of chemical species.[16][17]

For a discussion of other chemical bases for hypothetical self-replicating systems, see

See also

- Abiogenesis

- Artificial life

- Astrochicken

- Autopoiesis

- Complex system

- DNA replication

- Memetics

- Life

- Robot

- RepRap (self-replicated 3D printer)

- Self-replicating machine

- Space manufacturing

- Von Neumann universal constructor

- Virus

- Von Neumann machine (disambiguation)

- Self reconfigurable

References

- ^ "'Lifeless' prion proteins are 'capable of evolution'". BBC News. 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ von Neumann, John (1948). The Hixon Symposium. Pasadena, California. pp. 1–36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - PMID 33648631. For an interpretation in terms of the origin of life, see Maximilian, Ludwig (2021-04-03). "Solving the Chicken-and-the-Egg Problem – "A Step Closer to the Reconstruction of the Origin of Life"". SciTechDaily. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ a b HenryQuastler (1964) Emergence of Biological Organization, Yale University Press, New Haven Connecticut ASIN: B0000CMHJ2

- ^ Bernstein, Harris; Byerly, Henry C.; Hopf, Frederick A.; et al. (June 1983). "The Darwinian Dynamic". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 58 (2): 185–207. doi:10.1086/413216. JSTOR 2828805. S2CID 83956410

- ^ Freitas, Robert; Merkle, Ralph (2004). "Kinematic Self-Replicating Machines - General Taxonomy of Replicators". Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ^ Freitas, Robert; Merkle, Ralph (2004). "Kinematic Self-Replicating Machines - Freitas-Merkle Map of the Kinematic Replicator Design Space (2003–2004)". Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ^ For an image that does not show how this replicates, see: Eric W. Weisstein. "Sphinx." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Sphinx.html

- ^ For further illustrations, see Teaching TILINGS / TESSELLATIONS with Geo Sphinx Archived 2016-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The idea that life began as clay crystals is 50 years old". bbc.com. 2016-08-24. Archived from the original on 2016-08-24. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Modeling Kinematic Cellular Automata Final Report" (PDF). 2004-04-30. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ "Molecular Nanotechnology Guidelines". Foresight.org. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- PMID 21728135.

- PMID 28330337.

- ^ Wikisource:Advanced Automation for Space Missions

- PMID 21993758.

- ^ "Self-replication process holds promise for production of new materials". Science Daily. 2011-10-17. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- Notes

- von Neumann, J., 1966, The Theory of Self-reproducing Automata, A. Burks, ed., Univ. of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL.

- Advanced Automation for Space Missions, a 1980 NASA study edited by Robert Freitas

- Kinematic Self-Replicating Machines first comprehensive survey of entire field in 2004 by Robert Freitas and Ralph Merkle

- NASA Institute for Advance Concepts study by General Dynamics- concluded that complexity of the development was equal to that of a Pentium 4, and promoted a design based on cellular automata.

- Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter (detailed discussion and many examples)

- Kenyon, R., Self-replicating tilings, in: Symbolic Dynamics and Applications (P. Walters, ed.) Contemporary Math. vol. 135 (1992), 239-264.