Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

| Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Duloxetine, an example of an SNRI. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Selective Serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SNaRI |

| Use | Depression; Anxiety; Pain; Obesity; Menopausal symptoms |

| Biological target | Serotonin transporter; Norepinephrine transporter |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D000068760 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a class of

The human

SNRIs, along with SSRIs and NRIs, are

Medications

There are eight FDA approved SNRIs in the United States, with venlafaxine being the first drug to be developed in 1993 and levomilnacipran being the latest drug to be developed in 2013. The drugs vary by their other medical uses, chemical structure, adverse effects, and efficacy.[5]

| Medication | Brand name | FDA Indications | Approval Year | Chemical structure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desvenlafaxine[6] | Pristiq

Khedezla (ER) |

|

2007 |  |

The active metabolite of venlafaxine. It is believed to work in a similar manner, though some evidence suggests lower response rates compared to venlafaxine and duloxetine. It was introduced by Wyeth in May 2008 and was then the third approved SNRI.[7] |

| Duloxetine[8] | Cymbalta

Irenka |

|

2004 |  |

Approved for the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain in August 2004. Duloxetine is contraindicated in patients with heavy alcohol use or chronic liver disease, as duloxetine can increase the levels of certain liver enzymes that can lead to acute hepatitis or other diseases in certain at risk patients. The risk of liver damage appears to be only for patients already at risk, unlike the antidepressant nefazodone, which, though rare, can spontaneously cause liver failure in healthy patients.[12] Duloxetine is also approved for major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), diabetic neuropathy, chronic musculoskeletal pain, including chronic osteoarthritis pain and chronic low back pain.[10] Duloxetine also undergoes hepatic metabolism and has been shown to cause inhibition of the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP 2D6.[13] Caution should be taken when taking Duloxetine with other medications that are metabolized by CYP 2D6 as this may precipitate a potential drug-drug interaction.[13] |

| Levomilnacipran | Fetzima |

|

2013 |  |

The levorotating isomer of milnacipran. Under development for the treatment of depression in the United States and Canada, it was approved by the FDA for treatment of MDD in July 2013.

|

| Milnacipran | Ixel Savella Impulsor |

|

1996 |  |

Shown to be significantly effective in the treatment of depression and fibromyalgia.[14] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia in the United States in January 2009, however it is not approved for depression in that country.[citation needed] Milnacipran has been commercially available in Europe and Asia for several years.[citation needed] It was first introduced in France in 1996.[citation needed] |

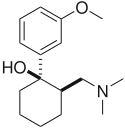

| Sibutramine | Meridia | 1997 |  |

An SNRI, which, instead of being developed for the treatment of depression, was widely marketed as an appetite suppressant for weight loss purposes. Sibutramine was the first drug for the treatment of obesity to be approved in 30 years.[16] It has been associated with increased cardiovascular events and strokes and has been withdrawn from the market in several countries and regions including the United States in 2010.[17]

| |

| Tramadol | Ultram |

|

1977 |  |

A dual weak opioid and SNRI. It was approved by the FDA in 1995, though it has been marketed in Germany since 1977. The drug is used to treat acute and chronic pain. It has shown effectiveness in the treatment of fibromyalgia, though it is not specifically approved for this purpose. The drug is also under investigation as an antidepressant and for the treatment of neuropathic pain. It is related in chemical structure to venlafaxine. Due to being an opioid, there is risk of abuse and addiction, but it does have less abuse potential, respiratory depression, and constipation compared to other opioids (hydrocodone, oxycodone, etc.).[18] |

| Venlafaxine | Effexor | 1994 |  |

The first and most commonly used SNRI. It was introduced by vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) of menopause and may be as effective as hormone replacement therapy (HRT).[20]

|

History

In 1952,

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the catecholamine hypothesis of emotion and its relation to depression was of wide interest and that the decreased levels of certain neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine might play a role in the pathogenesis of depression. This led to the development of fluoxetine, the first SSRI. The improved safety and tolerability profile of the SSRIs in patients with MDD, compared with TCAs and MAOIs, represented yet another important advance in the treatment of depression.[22]

Since the late 1980s, SSRIs have dominated the antidepressant drug market. Today, there is increased interest in antidepressant drugs with broader

Mechanism of action

Monoamines are connected to the pathophysiology of depression. Symptoms may occur because concentrations of neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, are insufficient, leading to downstream changes.[9][24] Medications for depression affect the transmission of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.[9] Older and less selective antidepressants like TCAs and MAOIs inhibit the reuptake or metabolism of norepinephrine and serotonin in the brain, which results in higher concentrations of neurotransmitters.[24] Antidepressants that have dual mechanisms of action inhibit the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine and, in some cases, inhibit with weak effect the reuptake of dopamine.[9] Antidepressants affect variable neuronal receptors such as muscarinic cholinergic, α1- and α2-adrenergic, H1-histaminergic, and

Tricyclic antidepressants

TCAs were the first medications that had dual mechanism of action. The mechanism of action of tricyclic secondary amine antidepressants is only partly understood. TCAs have dual inhibition effects on norepinephrine reuptake transporters and serotonin reuptake transporters. Increased norepinephrine and serotonin concentrations are obtained by inhibiting both of these transporter proteins. TCAs have substantially more affinity for norepinephrine reuptake proteins than the SSRIs. This is because of a formation of secondary amine TCA metabolites.[28][29]

In addition, the TCAs interact with

Norepinephrine interacts with postsynaptic α and β adrenergic receptor subtypes and presynaptic α2 autoreceptors. The α2 receptors include presynaptic

TCAs activate a negative feedback mechanism through their effects on presynaptic receptors. One probable explanation for the effects on decreased neurotransmitter release is that, as the receptors activate, inhibition of neurotransmitter release occurs (including suppression of voltage-gated Ca2+ currents and activation of G protein-coupled receptor-operated K+ currents). Repeated exposure of agents with this type of mechanism leads to inhibition of neurotransmitter release, but repeated administration of TCAs finally leads to decreased responses by α2 receptors. The desensitization of these responses may be due to increased exposure to endogenous norepinephrine or from the prolonged occupation of the norepinephrine transport mechanisms (via an allosteric effect). The adaptation allows the presynaptic synthesis and secretion of norepinephrine to return to, or even exceed, normal levels of norepinephrine in the synaptic clefts. Overall, inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake induced by TCAs leads to decreased rates of neuron firing (mediated through α2 autoreceptors), metabolic activity, and release of neurotransmitters.[29]

TCAs do not block dopamine transport directly but might facilitate dopaminergic effects indirectly by inhibiting dopamine transport into noradrenergic terminals of the cerebral cortex.[29] Because they affect so many different receptors, TCAs have adverse effects, poor tolerability, and an increased risk of toxicity.[27]

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) selectively inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and are a widely used group of antidepressants.

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Noradrenergic neurons are located in two major regions in the brain. These regions are

Assays have shown that SNRIs have insignificant penchant for mACh, α1 and α2 adrenergic, or H1 receptors.[26]

Dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Agents with dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (SNRIs) are sometimes called non-tricyclic serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Clinical studies suggest that compounds that increase the concentration in the synaptic cleft of both norepinephrine and serotonin are more successful than single acting agents in the treatment of depression, but the data is not conclusive whether SNRIs are a more effective treatment option over SSRIs for depression.[32][33][34]

The non-tricyclic SNRIs have several important differences that are based on pharmacokinetics, metabolism to active metabolites, inhibition of CYP isoforms, effect of drug-drug interactions, and the half-life of the nontricyclic SNRIs.[28][35]

Combination of mechanisms of action in a single active agent is an important development in psychopharmacology.[35]

Structure activity relationship

Aryloxypropanamine scaffold

Several reuptake inhibitors contain an aryloxypropanamine scaffold. This structural motif has potential for high affinity binding to biogenic amine transports.

Cycloalkanol ethylamine scaffold

Milnacipran

Milnacipran is structurally different from other SNRIs.

The conformation of milnacipran is an important part of its pharmacophore. Changing its

Future development of structure activity relationship

The application of an aryloxypropanamine scaffold has generated a number of potent MAOIs.[40] Before the development of duloxetine, the exploration of aryloxypropanamine structure activity relationships resulted in the identification of fluoxetine and atomoxetine. The same motif can be found in reboxetine where it is constrained in a morpholine ring system. Some studies have been made where the oxygen in reboxetine is replaced by sulfur to give arylthiomethyl morpholine. Some of the arylthiomethyl morpholine derivatives maintain potent levels of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. Dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition resides in different enantiomers for arylthiomethyl morpholine scaffold.[41] Possible drug candidates with dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitory activity have also been derived from piperazine, 3-amino-pyrrolidine and benzylamine templates.[42]

Clinical trials

Depression

Several studies have shown that antidepressant drugs which have combined serotonergic and noradrenergic activity are generally more effective than SSRIs, which act upon serotonin reuptake by itself. Serotonergic-noradrenergic antidepressant drugs may have a modest efficacy advantage compared to SSRIs in treating major depressive disorder (MDD),[43] but are slightly less well tolerated.[44] Further research is needed to examine the possible differences of efficacy in specific MDD sub-populations or for specific MDD symptoms, between these classes of antidepressant drugs.

Analgesic

Data from clinical trials have indicated that SNRIs might have pain relieving properties. Although the perception and transmission of pain stimuli in the central nervous system have not been fully elucidated, extensive data support a role for serotonin and norepinephrine in the modulation of pain. Findings from clinical trials in humans have shown these antidepressants can help to reduce pain and functional impairment in central and neuropathic pain conditions. This property of SNRIs might be used to reduce doses of other pain relieving medication and lower the frequency of safety, limited efficacy and tolerability issues.[45] Clinical research data have shown in patients with GAD that the SNRI duloxetine is significantly more effective than placebo in reducing pain-related symptoms of GAD, after short-term and long-term treatment. However, findings suggested that such symptoms of physical pain reoccur in relapse situations, which indicates a need for ongoing treatment in patients with GAD and concurrent painful physical symptoms.[46]

Indications

SNRIs have been tested for treatment of the following conditions:

- Major depressive disorder (MDD)

- Posttraumatic stress disorder(PTSD)

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Social anxiety disorder (SAD)

- Obsessive compulsive disorder[47]

- Panic disorder

- Neuropathic pain

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic musculoskeletal pain

Pharmacology

Route of administration

SNRIs are delivered orally, usually in the form of capsules or tablets. It is recommended to take SNRIs in the morning with breakfast, which does not affect drug levels, but may help with certain side effects.[48] Norepinephrine has activating effects in the body and therefore can cause insomnia in some patients if taken at bedtime.[49] SNRIs can also cause nausea, which is usually mild and goes away within a few weeks of treatment, but taking the medication with food can help alleviate this.[50]

Mode of action

The condition for which SNRIs are mostly indicated, major depressive disorder, was thought to be mainly caused by decreased levels of serotonin and

Recent studies have shown that depression may be linked to increased inflammatory response,[54] thus attempts at finding an additional mechanism for SNRIs have been made. Studies have shown that SNRIs as well as SSRIs have significant anti-inflammatory action on microglia[55] in addition to their effect on serotonin and norepinephrine levels. As such, it is possible that an additional mechanism of these drugs that acts in combination with the previously understood mechanism exist. The implication behind these findings suggests use of SNRIs as potential anti-inflammatories following brain injury or any other disease where swelling of the brain is an issue. However, regardless of the mechanism, the efficacy of these drugs in treating the diseases for which they have been indicated has been proven, both clinically and in practice.[improper synthesis?]

Pharmacodynamics

Most SNRIs function alongside

Activity profiles

| Compound | SERT | NET | ~Ratio (5-HT : NE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki | IC50 | Ki | IC50 | ||

| Venlafaxine | 7.8 | 145 | 1,920 | 1420 | 9.8:1 |

Des-venlafaxine |

40.2 | 47.3 | 558.4 | 531.3 | |

| Duloxetine | 0.07 | 3.7 | 1.17 | 20 | 5.4:1 |

| Atomoxetine | 87[62] | 5.4[62] | 0.06:1 (= 1:16) | ||

| Milnacipran | 8.44 | 151 | 22 | 68 | 0.45:1 (= 1:2.2) |

Levo-milnacipran |

11.2 | 19.0 | 92.2 | 10.5 | |

| All of the Ki and IC50 values are nM. The 5-HT/NE ratio is based on IC50 values for the SERT and NET.[61] | |||||

Pharmacokinetics

The half-life of venlafaxine is about 5 hours, and with once-daily dosing, steady-state concentration is achieved after about 3 days, though its active metabolite desvenlafaxine lasts longer.[59] The half-life of desvenlafaxine is about 11 hours, and steady-state concentrations are achieved after 4 to 5 days.[58] The half-life of duloxetine is about 12 hours (range: 8–17 hours), and steady-state is achieved after about 3 days.[10] Milnacipran has a half-life of about 6 to 8 hours, and steady-state levels are reached within 36 to 48 hours.[60]

Contraindications

SNRIs are contraindicated in patients taking

Due to the effects of increased

Side effects

Because the SNRIs and SSRIs act in similar ways to elevate serotonin levels, they share many side effects, though to varying degrees. The most common side effects include nausea/vomiting, sweating, loss of appetite, dizziness, headache, increase in suicidal thoughts, and sexual dysfunction.[68] Elevation of norepinephrine levels can sometimes cause anxiety, mildly elevated pulse, and elevated blood pressure. However, norepinephrine-selective antidepressants, such as reboxetine and desipramine, have successfully treated anxiety disorders.[69] People at risk for hypertension and heart disease should monitor their blood pressure.[15][58][59][10][60]

Sexual Dysfunction

SNRIs, similarly to SSRIs, can cause several types of sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, sexual anhedonia, and anorgasmia.[10][59][70] The two common sexual side effects are diminished interest in sex (libido) and difficulty reaching climax (anorgasmia), which are usually somewhat milder with SNRIs compared to SSRIs.[71] To manage sexual dysfunction, studies have shown that switching to or augmenting with bupropion or adding a PDE5 Inhibitor have decreased symptoms of sexual dysfunction.[72] Studies have shown that PDE5 Inhibitors, such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), vardenafil (Levitra), and avanafil (Stendra), have sometimes been helpful to decrease the sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction, although they have been shown to be more effective in men than women.[72]

Serotonin Syndrome

A serious, but rare, side effect of SNRIs is serotonin syndrome, which is caused by an excess of serotonin in the body. Serotonin syndrome can be caused by taking multiple serotonergic drugs, such as SSRIs or SNRIs. Other drugs that contribute to serotonin syndrome include MAO inhibitors, linezolid, tedizolid, methylene blue, procarbazine, amphetamines, clomipramine, and more.[73] Early symptoms of serotonin syndrome may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, agitation, confusion, muscle rigidity, dilated pupils, hyperthermia, rigidity, and goose bumps. More severe symptoms include fever, seizures, irregular heartbeat, delirium, and coma.[74][75][10] If signs or symptoms arise, discontinue treatment with serotonergic agents immediately.[74] It is recommended to washout 4 to 5 half-lives of the serotonergic agent before using an MAO inhibitor.[76]

Bleeding

Some studies suggest there are risks of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, especially venlafaxine, due to impairment of platelet aggregation and depletion of platelet serotonin levels.[77][78] Similarly to SSRIs, SNRIs may interact with anticoagulants, like warfarin. There is more evidence of SSRIs having higher risk of bleeding than SNRIs.[77] Studies have suggested caution when using SNRIs or SSRIs with high doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or naproxen due to an increased risk of upper GI bleeding.[34]

Visual problems

Similarly to other antidepressants, SNRI medications have been found to cause visual snow syndrome, a condition characterized by visual static, palinopsia (negative after image), nyctalopia (poor vision at night), and photophobia (brighter presentation of lights or highlighted colors). Evidence shows that 8.9% of those taking SNRIs experienced visual snow, 10.5% experienced palinopsia, 15.3% experienced photophobia, and 17.7% experienced nyctolopia as the result of SNRI prescription intake. Amitriptyline, and citalopram have also been reported to worsen or cause symptoms of VSS.[79]

Precautions

Starting an SNRI regimen

Due to the extreme changes in noradrenergic activity produced from norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition, patients that are just starting an SNRI regimen are usually given lower doses than their expected final dosing to allow the body to acclimate to the drug's effects. As the patient continues along at low doses without any side-effects, the dose is incrementally increased until the patient sees improvement in symptoms without detrimental side-effects.[80]

Discontinuation syndrome

As with SSRIs, the abrupt discontinuation of an SNRI usually leads to

Overdose

Causes

Overdosing on SNRIs can be caused by either drug combinations or excessive amounts of the drug itself. Venlafaxine is marginally more toxic in overdose than duloxetine or the SSRIs.[15][58][59][10][60][85]

Symptoms

Symptoms of SNRI overdose, whether it be a mixed drug interaction or the drug alone, vary in intensity and incidence based on the amount of medicine taken and the individuals sensitivity to SNRI treatment. Possible symptoms may include:[10]

- Somnolence

- Coma

- Serotonin syndrome

- Seizures

- Syncope

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Hypertension

- Hyperthermia

- Vomiting

Management

Overdose is usually treated symptomatically, especially in the case of serotonin syndrome, which requires treatment with cyproheptadine and temperature control based on the progression of the serotonin toxicity.[86] Patients are often monitored for vitals and airways cleared to ensure that they are receiving adequate levels of oxygen. Another option is to use activated carbon in the GI tract in order to absorb excess neurotransmitter.[10]

Comparison to SSRIs

Because SNRIs were developed more recently than SSRIs, there are relatively few of them. However, the SNRIs are among the most widely used antidepressants today. In 2009, Cymbalta and Effexor were the 11th- and 12th-most-prescribed branded drugs in the United States, respectively. This translates to the 2nd- and 3rd-most-common antidepressants, behind Lexapro (escitalopram), an SSRI.[87] In some studies, SNRIs demonstrated slightly higher antidepressant efficacy than the SSRIs (response rates 63.6% versus 59.3%).[43] However, in one study escitalopram had a superior efficacy profile to venlafaxine.[88]

Special populations

Pregnancy

No antidepressants are FDA approved during pregnancy.[89] Use of antidepressants during pregnancy may result in fetus abnormalities affecting functional development of the brain and behavior.[89]

Pediatrics

SSRIs and SNRIs have been shown to be effective in treating major depressive disorder and anxiety in pediatric populations.[90] However, there is a risk of increased suicidality in pediatric populations for treatment of major depressive disorder, especially with venlafaxine.[90] Fluoxetine is the only antidepressant that is approved for child/adolescent major depressive disorder.[91]

Geriatrics

Most antidepressants, including SNRIs, are safe and effective in the geriatric population. Decisions are often based on co-morbid conditions, drug interactions, and patient tolerance. Due to differences in body composition and metabolism, starting doses are often half that of the recommended dose for younger adults.[92]

Research

A systematic review that looked at the efficacy of antidepressants for pain relief concludes that only 11 of 42 comparisons showed evidence of efficacy. Seven of the eleven comparisons belong to the SNRI drug class.[93]

See also

- List of antidepressants

- Serotonin releasing agent (SRA)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)

- Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI)

References

- ^ Cleveland Clinic medical professional (2023-03-05). "SNRIs". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2024-01-09.

- PMID 19740668.

- S2CID 205396280.

- PMID 18691982.

- PMID 25643025.

- ^ S2CID 15063064.

- ^ PMID 19698900.

- S2CID 18022449.

- ^ PMID 16199241.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Cymbalta- duloxetine hydrochloride capsule, delayed release". DailyMed. 20 September 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "Yentreve (duloxetine hydrochloride) Hard Gastro-Resistant Capsules. Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Nefazodone hydrochloride tablet". DailyMed. 16 November 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ S2CID 22242897.

- ^ S2CID 5978467.

- ^ a b c d e "Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) Capsules C-IV. Full Prescribing Information (archived label)". Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL 60064, USA. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- PMID 12007530.

- ^ Rockoff JD, Dooren JC (October 8, 2010). "Abbott Pulls Diet Drug Meridia Off US Shelves". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- S2CID 22620947.

- ^ PMID 14512125.

- ^ PMID 24861828.

- S2CID 35064471.

- ^ a b Lieberman JA (2003). "History of the Use of Antidepressants in Primary Care" (PDF). Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 5 (S7): 6–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- .

- ^ S2CID 13228862.

- PMID 15320756.

- ^ S2CID 7989883.

- ^ S2CID 40022100.

- ^ a b c Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito SW (2008). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (6th ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 547–67, 581–582.

- ^ a b c d e Brunton, L.L., Lazo, J.S., Parker, K.L., eds. (2006). Goodman & Gilman's: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Silverthorn, D.U., ed. (2007). Human Physiology (4 ed.). San Francisco: Pearson. pp. 383–384.

- S2CID 23634771.

- PMID 26576188.

- PMID 29344343.

- ^ ISBN 9781496318299.

- ^ PMID 15664840.

- ^ PMID 16973367.

- PMID 18557608.

- ^ PMID 18207394.

- ^ PMID 18445525.

- PMID 19329313.

- PMID 15454233.

- PMID 18387300.

- ^ S2CID 45621773.

- PMID 16165158.

- PMID 20514212.

- PMID 19643572.

- PMID 21779536.

- S2CID 33518952.

- PMID 28791566.

- ^ "Helpful for chronic pain in addition to depression". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- S2CID 250646781.

- PMID 18494537.

- PMID 15910402.

- PMID 21485745.

- ^ S2CID 39281923.

- ^ "Cambridge University Press - Service Announcement".

- S2CID 37792842.

- ^ a b c d "Pristiq Extended-Release- desvenlafaxine succinate tablet, extended release". DailyMed. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Effexor XR- venlafaxine hydrochloride capsule, extended release". DailyMed. 29 August 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Savella- milnacipran hydrochloride tablet, film coated Savella- milnacipran hydrochloride kit". DailyMed. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ PMID 28503727.

- ^ PMID 23397050.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (Dec 2012). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ S2CID 37959124.

- PMID 29158677.

- ^ McIntyre RS et al. The hepatic safety profile of duloxetine: a review. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(3):281–285.

- PMID 29315692.

- ^ "SNRI Antidepressants". poison.org. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- PMID 11838623.

- .

- PMID 16848675.

- ^ PMID 29955469.

- ^ "Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it". www.mdedge.com. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ PMID 18625822.

- ^ "SNRI Antidepressants". poison.org. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- S2CID 145217439.

- ^ PMID 21743381.

- PMID 26579809.

- PMID 35235167.

- ^ "Duloxetine: Drug Information". UpToDate. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- PMID 17445831.

- PMID 26834969.

- PMID 30016772.

- S2CID 51677365.

- PMID 24167687.

- PMID 29493999. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ "2009 Top 200 branded drugs by total prescriptions" (PDF). SDI/Verispan, VONA, full year 2009. www.drugtopics.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- PMID 17394446.

- ^ PMID 30123033.

- ^ PMID 29588049.

- S2CID 29031880.

- PMID 25037293.

- PMID 36725015.