Serotonin transporter

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 17: 30.19 – 30.24 Mb | Chr 11: 76.89 – 76.92 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

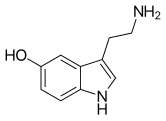

The serotonin transporter (SERT or 5-HTT) also known as the sodium-dependent serotonin transporter and solute carrier family 6 member 4 is a

This transport of serotonin by the SERT protein terminates the action of serotonin and recycles it in a sodium-dependent manner. Many antidepressant medications of the

Mechanism of action

Serotonin-reuptake transporters are dependent on both the concentration of potassium ion in the

The serotonin transporter first binds a sodium ion, followed by the serotonin, and then a chloride ion; it is then allowed, thanks to the membrane potential, to flip inside the cell freeing all the elements previously bound. Right after the release of the serotonin in the cytoplasm a potassium ion binds to the transporter which is now able to flip back out returning to its active state.[9]

Function

The serotonin transporter removes serotonin from the synaptic cleft back into the synaptic

Neurons communicate by using chemical messengers like serotonin between cells. The transporter protein, by recycling serotonin, regulates its concentration in a gap, or synapse, and thus its effects on a receiving neuron's receptors.

Medical studies have shown that changes in serotonin transporter metabolism appear to be associated with many different phenomena, including

The serotonin transporter is also present in

Pharmacology

In 1995 and 1996, scientists in Europe had identified the polymorphism

SERT spans the plasma membrane 12 times. It belongs to the NE, DA, SERT monoamine transporter family. Transporters are important sites for agents that treat

Following the elucidation of structures of the homologous bacterial transporter, LeuT, co-crystallized with

Ligands

- DASB

- compound 4b: Ki = 17 pM; 710-fold and 11,100-fold selective over DAT and NET[20]

- compound (+)-12a: Ki = 180 pM at hSERT; >1000-fold selective over hDAT, hNET, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT6.[21] Isosteres[22]

- 3-cis-(3-Aminocyclopentyl)indole 8a: Ki = 220 pM[23]

- allosteric modulator: 3′-Methoxy-8-methyl-spiro{8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane-3,5′(4′H)-isoxazole} (compound 7a)[24]

- allosteric modulator: p-Trifluoromethyl-methcathinone[25]

Genetics

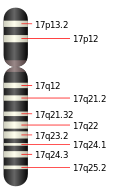

The gene that encodes the serotonin transporter is called solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4 (SLC6A4, see Solute carrier family). In humans the gene is found on chromosome 17 on location 17q11.1–q12.[27]

Mutations associated with the gene may result in changes in serotonin transporter function, and experiments with mice have identified more than 50 different phenotypic changes as a result of genetic variation. These phenotypic changes may, e.g., be increased

- Length variation in the serotonin-transporter-gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR)

- single nucleotide polymorphism(SNP) in the 5-HTTLPR

- rs25532 — another SNP in the 5-HTTLPR

- STin2 — a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) in the functional intron2

- G56A on the second exon

- I425V on the ninth exon

Length variation in 5-HTTLPR

According to a 1996 article in The Journal of Neurochemistry, the

In addition to altering the expression of SERT protein and concentrations of extracellular serotonin in the brain, the 5-HTTLPR variation is associated with changes in brain structure. One 2005 study found less grey matter in perigenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala for short allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism compared to subjects with the long/long genotype.[32]

In contrast, a 2008 meta-analysis found no significant overall association between the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and autism.[33] A hypothesized gene–environment interaction between the short/short allele of the 5-HTTLPR and life stress as predictor for major depression has suffered a similar fate: after an influential[34] initial report in 2003[35] there were mixed results in replication in 2008,[36] and a 2009 meta-analysis was negative.[37] See 5-HTTLPR for more information.

rs25532

rs25532 is a SNP (C>T) close to the site of 5-HTTLPR. It has been examined in connection with

I425V

I425V is a rare mutation on the ninth exon. In 2003, researchers from Japan and the US reported that they had found this genetic variation in unrelated families with

VNTR in STin2

Another noncoding polymorphism is a

: 9, 10 and 12 repeats. A meta-analysis has found that the 12 repeat allele of the STin2 VNTR polymorphism had some minor (with odds ratio 1.24), but statistically significant, association with schizophrenia.[42] A 2008 meta-analysis found no significant overall association between the STin2 VNTR polymorphism andThe polymorphism has also been related to

Neuroimaging

The distribution of the serotonin transporter in the

Neuroimaging and genetics

Studies on the serotonin transporter have combined neuroimaging and genetics methods, e.g., a voxel-based morphometry study found less grey matter in perigenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala for short allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism compared to subjects with the long/long genotype.[32]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000108576 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020838 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "SLC6A4 Gene (Protein Coding)".

- ^ "SLC6A4 - Sodium-dependent serotonin transporter - Homo sapiens (Human) - SLC6A4 gene & protein".

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-374019-9.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: SLC6A4 solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4".

- ^ "Mechanism of Action of the Serotonin Transporter". web.williams.edu. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- S2CID 12630172.

- PMID 18413401.

- S2CID 8474414.

- S2CID 42037860.

- PMID 9154246.

- PMID 17690258.

- PMID 19948720.

- PMID 19213730.

- PMID 20055463.

- PMID 24037379.

- PMID 15686927.

- PMID 16162005.

- PMID 17766113.

- PMID 20949929.

- PMID 23022052.

- S2CID 128363044.

- PMID 19179540.

- ^ S2CID 12459610.

- ^ S2CID 7563088.

- S2CID 42037860.

- S2CID 35503987.

- S2CID 26655014.

- ^ S2CID 1864631.

- ^ S2CID 9491697.

- S2CID 24236284.

- S2CID 146500484.

- S2CID 24432263.

- PMID 19531786.

- PMID 18055562.

- S2CID 2171955. News article:

- "Gene Found for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Mental Health E-News. Reuters. 27 October 2003. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- ^

Delorme R, Betancur C, Wagner M, Krebs MO, Gorwood P, Pearl P, Nygren G, Durand CM, Buhtz F, Pickering P, Melke J, Ruhrmann S, Anckarsäter H, Chabane N, Kipman A, Reck C, Millet B, Roy I, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Maier W, Råstam M, Gillberg C, Leboyer M, Bourgeron T (December 2005). "Support for the association between the rare functional variant I425V of the serotonin transporter gene and susceptibility to obsessive compulsive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 10 (12): 1059–61. PMID 16088327.

- ^ Stephen Wheless. ""The OCD Gene" Popular Press v. Scientific Literature: Is SERT Responsible for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?". Davidson College. Retrieved 12 June 2008.

- S2CID 29240701.

- PMID 12851635.

- S2CID 7423923.

- S2CID 18932686.

- S2CID 22034290.

- doi:10.2174/157340006775101508. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 July 2011.

- S2CID 41664835.