Sexual fetishism

| Sexual fetishism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Foot fetishism, one of the most common sexual fetishes | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Sexual fetishism or erotic fetishism is a sexual fixation on a nonliving object or nongenital body part.[1] The object of interest is called the fetish; the person who has a fetish for that object is a fetishist.[2] A sexual fetish may be regarded as a non-pathological aid to sexual excitement, or as a mental disorder if it causes significant psychosocial distress for the person or has detrimental effects on important areas of their life.[1][3] Sexual arousal from a particular body part can be further classified as partialism.[4]

While medical definitions restrict the term sexual fetishism to objects or body parts,[1] fetish can, in common discourse, also refer to sexual interest in specific activities.[5]

Definitions

In common parlance, the word fetish is used to refer to any sexually arousing stimuli, not all of which meet the medical criteria for fetishism.

Originally, most medical sources defined fetishism as a sexual interest in non-living objects, body parts or secretions. The publication of the

Types

In a review of 48 cases of clinical fetishism in 1983, fetishes included clothing (58.3%), rubber and rubber items (22.9%), footwear (14.6%), body parts (14.6%), leather (10.4%), and soft materials or fabrics (6.3%).[7]

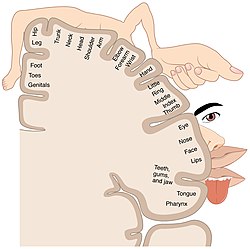

A 2007 study counted members of Internet discussion groups with the word fetish in their name. Of the groups about body parts or features, 47% belonged to groups about feet (

Erotic asphyxiation is the use of choking to increase the pleasure in sex. The fetish also includes an individualized part that involves choking oneself during the act of masturbation, which is known as auto-erotic asphyxiation. This usually involves a person being connected and strangled by a homemade device that is tight enough to give them pleasure but not tight enough to suffocate them to death. This is dangerous due to the issue of hyperactive pleasure seeking which can result in strangulation when there is no one to help if the device gets too tight and strangles the user.[8]

Devotism involves being attracted to disability or body modifications on another person that are the result of amputation for example. Devotism is only a sexual fetish when the person who has the fetish considers the amputated body part on another person the object of sexual interest.[9]

Cause

Fetishism usually becomes evident during puberty, but may develop prior to that.[1] No single cause for fetishism has been conclusively established.[10]

Some explanations invoke classical conditioning. In several experiments, men have been conditioned to show arousal to stimuli like boots, geometric shapes or penny jars by pairing these cues with conventional erotica.[11] According to John Bancroft, conditioning alone cannot explain fetishism, because it does not result in fetishism for most people. He suggests that conditioning combines with some other factor, such as an abnormality in the sexual learning process.[10]

Theories of

Neurological differences may play a role in some cases.

Various explanations have been put forth for the rarity of female fetishists. Most fetishes are visual in nature, and males are thought to be more sexually sensitive to visual stimuli.[17] Roy Baumeister suggests that male sexuality is unchangeable, except for a brief period in childhood during which fetishism could become established, while female sexuality is fluid throughout life.[18]

Diagnosis

The ICD-10 defines fetishism as a reliance on non-living objects for sexual arousal and satisfaction. It is only considered a disorder when fetishistic activities are the foremost source of sexual satisfaction, and become so compelling or unacceptable as to cause distress or interfere with normal sexual intercourse.[3] The ICD's research guidelines require that the preference persists for at least six months, and is markedly distressing or acted on.[19]

Under the

The ReviseF65 project has campaigned for the ICD diagnosis to be abolished completely to avoid

Treatment

According to the

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one popular approach. Cognitive behavioral therapists teach clients to identify and avoid antecedents to fetishistic behavior, and substitute non-fetishistic fantasies for ones involving the fetish. Aversion therapy and covert conditioning can reduce fetishistic arousal in the short term, but requires repetition to sustain the effect. Multiple case studies have also reported treating fetishistic behavior with psychodynamic approaches.[21]

Occurrence

The

Fetishism to the extent that it becomes a disorder appears to be rare, with less than 1% of general psychiatric patients presenting fetishism as their primary problem. It is also uncommon in forensic populations.[17]

History

The word fetish derives from the French fétiche, which comes from the Portuguese feitiço ("spell"), which in turn derives from the Latin facticius ("artificial") and facere ("to make").[25] A fetish is an object believed to have supernatural powers, or in particular, a human-made object that has power over others. Essentially, fetishism is the attribution of inherent value or powers to an object. Fétichisme was first used in an erotic context by Alfred Binet in 1887.[26][27] A slightly earlier concept was Julien Chevalier's azoophilie.[28]

Early perspectives on cause

Alfred Binet suspected fetishism was the pathological result of associations. He argued that, in certain vulnerable individuals, an emotionally rousing experience with the fetish object in childhood could lead to fetishism.[29] Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis also believed that fetishism arose from associative experiences, but disagreed on what type of predisposition was necessary.[30]

The sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld followed another line of thought when he proposed his theory of partial attractiveness in 1920. According to his argument, sexual attractiveness never originates in a person as a whole but always is the product of the interaction of individual features. He stated that nearly everyone had special interests and thus suffered from a healthy kind of fetishism, while only detaching and overvaluing of a single feature resulted in pathological fetishism. Today, Hirschfeld's theory is often mentioned in the context of gender role specific behavior: females present sexual stimuli by highlighting body parts, clothes or accessories; males react to them.

Sigmund Freud believed that sexual fetishism in men derived from the unconscious fear of the mother's genitals, from men's universal fear of castration, and from a man's fantasy that his mother had had a penis but that it had been cut off. He did not discuss sexual fetishism in women.

In 1951,

Other animals

Human fetishism has been compared to

Possible

See also

Clothing fetishism and fetish-related

References

- ^ a b c d e f American Psychiatric Association, ed. (2013). "Fetishistic Disorder, 302.81 (F65.0)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 700.

- ^ "Common Misunderstandings of Fetishism". K. M. Vekquin. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Fetishism, F65.0" (PDF). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization. p. 170. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Milner, J. S., & Dopke, C. A. (1997). Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified: Psychopathology and theory. In D. R. Laws and W. O'Donohue (Eds.), Sexual deviance: Theory, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford.

- ^ PMID 17304204.

- ^ S2CID 22820928.

- S2CID 37994356.

- S2CID 6029257.

- ^ a b Bancroft, John (2009). Human Sexuality and Its Problems. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 283–286.

- ISBN 9781593856052.

- ISBN 9781593856052.

- ^ S2CID 12421026. Archived from the original(PDF) on 9 August 2017.

- PMID 7883483.

- ISBN 9781593856052.

- PMID 13202455.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISBN 9781593856052.

- S2CID 35777544. Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 January 2012.

- ^ The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research (PDF). World Health Organization. 1993. p. 165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ S2CID 7120928.

- ^ ISBN 9781593856052.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 205894747.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 33785479.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ]

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "fetish (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Binet, A. (1887). "Du fétichisme dans l'amour". Revue Philosophiqu. 24: 143–167.

- ^ Bullough, V. L. (1995). Science in the bedroom: A history of sex research. Basic Books. p. 42. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- PMID 32605397.

- PMID 8936751.

- PMID 13364343.

- ^ Winnicott, D. W. (1953) Übergangsobjekte und Übergangsphänomene: eine Studie über den ersten, nicht zum Selbst gehörenden Besitz. (German) Presentation 1951, 1953. In: Psyche 23, 1969.

- ^ PMID 3772304.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ISBN 9781317913528.

Further reading

- Bass, Alan (2018). Fetishism, Psychoanalysis, and Philosophy: The Iridescent Thing. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-55640-9.

- Bienvenu, Robert (2003). The Development of Sadomasochism as a Cultural Style in the Twentieth-Century United States. Online PDF under Sadomasochism as a Cultural Style. Archived 16 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Gates, Katharine (1999). Deviant Desires: Incredibly Strange Sex. Juno Books. ISBN 978-1-890451-03-5.

- Kaplan, Louise J. (1991). Female Perversions: The Temptations of Emma Bovary. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-26233-0.

- Love, Brenda (1994). The Encyclopedia of Unusual Sex Practices. Barricade Books. ISBN 978-1-56980-011-9.

- Steele, Valerie (1995). Fetish: Fashion, Sex, and Power. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509044-4.

- Utley, Larry; Autumn Carey-Adamme (2002). Fetish Fashion: Undressing the Corset. Green Candy Press. ISBN 978-1-931160-06-3.

- Коловрат Ю. А. Сексуальное волховство и фаллоктенические культы древних славян // История Змиевского края. – Змиев. – 19.10.2008.