Shapur I

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (January 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

| Shapur I 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 | |

|---|---|

House of Sasan | |

| Father | Ardashir I |

| Mother | Murrod or Denag |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I;

Shapur later took advantage of the political turmoil within the Roman Empire by undertaking a second expedition against it in 252/3–256, sacking the cities of Antioch and Dura-Europos. In 260, during his third campaign, he defeated and captured the Roman emperor, Valerian. He did not seem interested in permanently occupying the Roman provinces, choosing instead to resort to plundering and pillaging, gaining vast amounts of riches. The captives of Antioch, for example, were allocated to the newly reconstructed city of Gundeshapur, later famous as a center of scholarship. In the 260s, subordinates of Shapur suffered setbacks against Odaenathus, the king of Palmyra. According to Shapur's inscription at Hajiabad, he still remained active at the court in his later years, participating in archery. He died of illness in Bishapur, most likely in May 270.[2]

Shapur was the first Iranian monarch to use the title of "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians"; beforehand the royal titulary had been "King of Kings of Iranians". He had adopted the title due to the influx of Roman citizens whom he had deported during his campaigns. However, it was first under his son and successor

Etymology

"Shapur" was a popular name in

Background

According to the semi-legendary Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan, a Middle Persian biography of Ardashir I,[3] the daughter of the Parthian king Artabanus IV, Zijanak, attempted to poison her husband Ardashir. Discovering her intentions, Ardashir ordered her to be executed. Finding out about her pregnancy, the mobads (priests) were against it. Nevertheless, Ardashir still demanded her execution, which led the mobads to conceal her and her son Shapur for seven years, until the latter was identified by Ardashir, who chooses to adopt him based on his virtuous traits.[4] This type of narrative is repeated in Iranian historiography. According to 5th-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, the Median king Astyages wanted to have his grandson Cyrus killed because he believed that he would one day overthrow him. A similar narrative is also found in the story of the mythological Iranian king Kay Khosrow.[4] According to the modern historian Bonner, the story of Shapur's birth and uprising "may conceal a marriage between Ardashir and an Arsacid princess or perhaps merely a noble lady connected with the Parthian aristocracy."[5] On his inscriptions, Shapur identifies his mother as a certain Murrod.[5]

Background and state of Iran

Shapur I was a son of Ardashir I and his wife

Pars, a region in the southwestern

Under

Peace was made between the two empires the following year, with the Arsacids keeping most of Mesopotamia.[20] However, Artabanus IV still had to deal with his brother Vologases VI, who continued to mint coins and challenge him.[20] The Sasanian family had meanwhile quickly risen to prominence in Pars, and had now under Ardashir begun to conquer the neighbouring regions and more far territories, such as Kirman.[19][21] At first, Ardashir I's activities did not alarm Artabanus IV, until later, when the Arsacid king finally chose to confront him.[19]

Early life and co-rule

Shapur, as portrayed in the Sasanian

Military career

The Eastern Front

The Eastern provinces of the fledgling Sasanian Empire bordered on the land of the

Soon after the death of his father in 241 CE, Shapur felt the need to cut short the campaign they had started in Roman Syria, and reassert Sasanian authority in the East, perhaps because the Kushan and Saka kings were lax in abiding to their tributary status. However, he first had to fight "The Medes of the Mountains"—as we will see possibly in the mountain range of

I, the Mazda-worshipping lord, Shapur, king of kings of Iran and An-Iran… (I) am the Master of the Domain of Iran (Ērānšahr) and possess the territory of Persis, Parthian… Hindestan, the Domain of the Kushan up to the limits of Paškabur and up to Kash, Sughd, and Chachestan.

— Naqsh-e Rostam inscription of Shapur I

He seems to have garrisoned the Eastern territories with POW's from his previous campaign against the Medes of the Mountains. Agathias claims

First Roman war

Ardashir I had, towards the end of his reign, renewed the war against the

The Romans later invaded eastern Mesopotamia but faced tough resistance from Shapur I who returned from the East. Timesitheus died under uncertain circumstances and was succeeded by Philip the Arab. The young emperor Gordian III went to the Battle of Misiche and was either killed in the battle or murdered by the Romans after the defeat. The Romans then chose Philip the Arab as Emperor. Philip was not willing to repeat the mistakes of previous claimants, and was aware that he had to return to Rome to secure his position with the Senate. Philip concluded a peace with Shapur I in 244; he had agreed that Armenia lay within Persia's sphere of influence. He also had to pay an enormous indemnity to the Persians of 500,000 gold denarii.[1] Philip immediately issued coins proclaiming that he had made peace with the Persians (pax fundata cum Persis).[32] However, Philip later broke the treaty and seized lost territory.[1]

Shapur I commemorated this victory on several rock reliefs in Pars.

Second Roman war

Shapur I invaded Mesopotamia in 250 but again, serious trouble arose in Khorasan and Shapur I had to march over there and settle its affair.

Having settled the affair in Khorasan he resumed the invasion of Roman territories, and later annihilated a Roman force of 60,000 at the Battle of Barbalissos. He then burned and ravaged the Roman province of Syria and all its dependencies.

Shapur I then reconquered Armenia, and incited Anak the Parthian to murder the king of Armenia, Khosrov II. Anak did as Shapur asked, and had Khosrov murdered in 258; yet Anak himself was shortly thereafter murdered by Armenian nobles.[33] Shapur then appointed his son Hormizd I as the "Great King of Armenia". With Armenia subjugated, Georgia submitted to the Sasanian Empire and fell under the supervision of a Sasanian official.[1] With Georgia and Armenia under control, the Sasanians' borders on the north were thus secured.

During Shapur's invasion of

The victory over Valerian is presented in a mural at

However, the Persian forces were later defeated by the Roman officer

The

Interactions with minorities

Shapur is mentioned many times in the

Roman prisoners of war

Shapur's campaigns deprived the Roman Empire of resources while restoring and substantially enriching his own treasury, by

Death

In Bishapur, Shapur died of an illness. His death came in May 270 and he was succeeded by his son, Hormizd I. Two of his other sons, Bahram I and Narseh, would also become kings of the Sasanian Empire, while another son, Shapur Meshanshah, who died before Shapur, sired children who would hold exalted positions within the empire.[1]

Government

Governors during his reign

Under Shapur, the Sasanian court, including its territories, were much larger than that of his father. Several governors and vassal-kings are mentioned in his inscriptions; Ardashir, governor of

Officials during his reign

Several names of Shapur's officials are carved on his inscription at

Army

Under Shapur, the Iranian military experienced a resurgence after a rather long decline in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, which gave the Romans the opportunity to undertake expeditions into the Near East and Mesopotamia during the end of the Parthian Empire.

Although Iranian society was greatly militarised and its elite designated themselves as a "warrior nobility" (arteshtaran), it still had a significantly smaller population, was more impoverished, and was a less centralised state compared to the Roman Empire.

Use of war elephants is also attested under Shapur, who made use of them to demolish the city of Hatra.[44] He may also have used them against Valerian, as attested in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings).[45]

Monuments

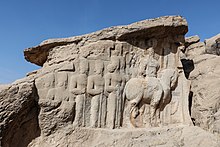

Shapur I left other reliefs and rock inscriptions. A relief at

From his titles we learn that Shapur I claimed sovereignty over the whole earth, although in reality his domain extended little farther than that of Ardashir I. Shapur I built the great town

Religious policy

In all records Shapur calls himself mzdysn ("Mazda-worshipping"). His inscription at the

During the reign of Shapur, Manichaeism, a new religion founded by the Iranian prophet Mani, flourished. Mani was treated well by Shapur, and in 242, the prophet joined the Sasanian court, where he tried to convert Shapur by dedicating his only work written in Middle Persian, known as the Shabuhragan. Shapur, however, did not convert to Manichaeism and remained a Zoroastrian.[47]

Coinage and imperial ideology

While the titulage of Ardashir was "King of Kings of Iran(ians)", Shapur slightly changed it, adding the phrase "and non-Iran(ians)".[48] The extended title demonstrates the incorporation of new territory into the empire, however what was precisely seen as "non-Iran(ian)" (aneran) is not certain.[49] Although this new title was used on his inscriptions, it was almost never used on his coinage.[50] The title first became regularised under Hormizd I.[51]

Cultural depictions

Shapur appears in Harry Sidebottom's historical fiction novel series as one of the enemies of the series protagonist Marcus Clodius Ballista, career soldier in a third-century Roman army.

Rating

See also

- Shapour I's inscription in Ka'ba-ye Zartosht

- Shapour I's inscription in Naqsh-e Rostam

- Siege of Dura Europos (256)

Notes

- ^ Also spelled "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians".

- ^ Artabanus IV is erroneously known in older scholarship as Artabanus V. For further information, see Schippmann (1986a, pp. 647–650)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Shahbazi 2002.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. "Shapur I". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Bonner 2020, p. 25.

- ^ a b Stoneman, Erickson & Netton 2012, p. 12.

- ^ a b Bonner 2020, p. 49.

- ^ Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2002). "Šāpur I". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. London et al.

- ISBN 978-1463206161

- ^ Gignoux 1994, p. 282.

- ^ a b Olbrycht 2016, pp. 23–32.

- ^ Daryaee 2010, p. 242.

- ^ a b Rezakhani 2017b, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c Wiesehöfer 2000a, p. 195.

- ^ a b Wiesehöfer 2009.

- ^ Wiesehöfer 2000b, p. 195.

- ^ a b Shayegan 2011, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f Daryaee 2010, p. 249.

- ^ Daryaee 2012, p. 187.

- ^ a b c Schippmann 1986a, pp. 647–650.

- ^ a b c Daryaee 2014, p. 3.

- ^ Schippmann 1986b, pp. 525–536.

- ^ a b Shahbazi 2004, pp. 469–470.

- ^ Rajabzadeh 1993, pp. 534–539.

- ^ a b Shahbazi 2005.

- ^ a b c McDonough 2013, p. 601.

- ^ Thaalibi 485–486 even ascribes the founding of Badghis and Khwarazm to Ardashir I

- ISBN 978-0521246934.

- ^ W. Soward, "The Inscription Of Shapur I At Naqsh-E Rustam In Fars", sasanika.org, 3.

Cf. F. Grenet, J. Lee, P. Martinez, F. Ory, “The Sasanian Relief at Rag-i Bibi (Northern Afghanistan)” in G. Hermann, J. Cribb (ed.), After Alexander. Central Asia before Islam (London 2007), pp. 259–260 - ^ Rezakhani 2017a, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Agathias 4.24.6–8; Panegyrici Latini N3.16.25; Thaalibi 495; Arthur Christensen (1944). L'Iran sous les Sassanides. Copenhague. p. 214.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Raditsa 2000, p. 125.

- ^ Southern 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Hovannisian, The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, p. 72

- ^ Frye 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Grishman, R. (1995). Iran From the Beginning Until Islam.

- ^ A. Tafazzoll (1990). History of Ancient Iran. p. 183.

- ^ Who's Who in the Roman World By John Hazel

- ^ Babylonia Judaica in the Talmudic Period By A'haron Oppenheimer, Benjamin H. Isaac, Michael Lecker

- ^ Frye 1984, p. 299.

- ^ Frye 1984, p. 373.

- ^ Daryaee & Rezakhani 2017, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e McDonough 2013, p. 603.

- ^ a b c McDonough 2013, p. 604.

- ^ Daryaee 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Daryaee 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Skjærvø 2011, pp. 608–628.

- ISBN 3-88309-043-3.

- ^ Shayegan 2013, p. 805.

- ^ Shayegan 2004, pp. 462–464.

- ^ Curtis & Stewart 2008, pp. 21, 23.

- ^ Curtis & Stewart 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Do54was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tabari 1999, p. 27.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sha2002was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Sources

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir(1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. Vol. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Bonner, Michael (2020). The Last Empire of Iran. New York: Gorgias Press. pp. 1–406. ISBN 978-1-4632-0616-1.

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopaedia Iranica. London et al.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2008). The Sasanian Era. I.B. Tauris. pp. 1–200. ISBN 978-0-85771-972-0.

- ISBN 978-0-85771-666-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2010). "Ardashir and the Sasanians' Rise to Power". Anabasis. University of California: 236–255.

- ISBN 978-0-19-973215-9.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2016). "From Terror to Tactical Usage: Elephants in the Partho-Sasanian Period". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-208-2.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- ISBN 978-3-406-09397-5.

- Frye, R.N. (2000). "The Political History of Iran under the Sasanians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3, Part 1: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press.

- Gignoux, Ph. (1983). "Ādur-Anāhīd". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 5. London et al. p. 472.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gignoux, Philippe (1994). "Dēnag". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 3. p. 282.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-61069-391-2. (2 volumes)

- McDonough, Scott (2011). "The Legs of the Throne: Kings, Elites, and Subjects in Sasanian Iran". In Arnason, Johann P.; Raaflaub, Kurt A. (eds.). The Roman Empire in Context: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 290–321. ISBN 978-1-4443-9018-6.

- McDonough, Scott (2013). "Military and Society in Sasanian Iran". In Campbell, Brian; Tritle, Lawrence A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Warfare in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–783. ISBN 978-0-19-530465-7.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016). "Dynastic Connections in the Arsacid Empire and the Origins of the House of Sāsān". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-208-2.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Rajabzadeh, Hashem (1993). "Dabīr". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 5. pp. 534–539.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4724-2552-2.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017a). "From the Kushans to the Western Turks". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 199–227. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017b). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013). "Sasanian Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973330-9.

- Raditsa, Leo (2000). "Iranians in Asia Minor". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3, Part 1: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–115.

- Schippmann, K. (1986a). "Artabanus (Arsacid kings)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 647–650.

- Schippmann, K. (1986b). "Arsacids ii. The Arsacid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 525–536.

- Schmitt, R. (1986). "Artaxerxes". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 654–655.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1988). "Bahrām I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. pp. 514–522.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2002). "Šāpur I". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozdgān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 469–470.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2004). "Hormozd I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 462–464.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76641-8.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2013). "Sasanian Political Ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973330-9.

- Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2011). "Kartir". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XV, Fasc. 6. pp. 608–628.

- Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw; Tessmann, Anna (2015). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Stoneman, Richard; Erickson, Kyle; Netton, Ian Richard (2012). The Alexander Romance in Persia and the East. Barkhuis. ISBN 978-94-91431-04-3.

- Southern, Pat (2003). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Taylor & Francis.

- Vevaina, Yuhan; Canepa, Matthew (2018). "Ohrmazd". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Weber, Ursula (2016). "Narseh". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (1986). "Ardašīr I i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4. pp. 371–376.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000b). "Frataraka". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 2. p. 195.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000a). "Fārs ii. History in the Pre-Islamic Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2001). Ancient Persia. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-675-1.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2009). "Persis, Kings of". Encyclopaedia Iranica.