Shia Islam

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Shia Islam (

Shia Islam is based on a

Shia Islam is the

Terminology

The word Shia derives from the Arabic term Shīʿat ʿAlī, meaning "partisans of Ali", "followers of Ali" or "faction of Ali".

The term Shia was first used during Muhammad's lifetime.

Beliefs

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: cluttered, inconsistent, and confusing. (October 2022) |

Shia Islam encompasses various denominations and subgroups,[3] all bound by the belief that the leader of the Muslim community (Ummah) should hail from Ahl al-Bayt, the family of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[14] It embodies a completely independent system of religious interpretation and political authority in the Muslim world.[15][16]

Alī: Muhammad's Rightful Successor

Shia Muslims believe that just as a

Profession of faith (Shahada)

The Shia version of the Shahada, the Islamic profession of faith, differs from that of the Sunnīs.[21] The Sunnī version of the Shahada states "There is no god except God, Muhammad is the messenger of God", but to this declaration of faith Shia Muslims append the phrase Ali-un-Waliullah (علي ولي الله: "Ali is the Wali (custodian) of God"). The basis for the Shia belief in Ali as the Wali of God is derived from the Quranic verse 5:55.

This additional phrase to the declaration of faith embodies the Shia emphasis on the inheritance of authority through Muhammad's family and lineage. The three clauses of the Shia version of the Shahada thus address the fundamental Islamic beliefs of Tawḥīd (unity and oneness of God), Nubuwwah (the prophethood of Muhammad), and Imamah (the Imamate, leadership of the faith).[22]

Infallibility (Ismah)

Ismah is the concept of

According to Shia Muslim theologians, infallibility is considered a rational, necessary precondition for spiritual and religious guidance. They argue that since God has commanded absolute obedience from these figures, they must only order that which is right. The state of infallibility is based on the Shia interpretation of the verse of purification.[26][27] Thus, they are the most pure ones, the only immaculate ones preserved from, and immune to, all uncleanness.[28] It does not mean that supernatural powers prevent them from committing a sin, but due to the fact that they have absolute belief in God, they refrain from doing anything that is a sin.[23]

They also have a complete knowledge of God's will. They are in possession of all knowledge brought by the angels to the prophets (nabī) and the messengers (rāsūl). Their knowledge encompasses the totality of all times. Thus, they are believed to act without fault in religious matters.[29] Shia Muslims regard Ali as the successor of Muhammad not only ruling over the entire Muslim community in justice, but also interpreting the Islamic faith, practices, and its esoteric meaning. Ali is regarded as a "perfect man" (al-insan al-kamil) similar to Muhammad, according to the Shia viewpoint.[30]

Occultation (Ghaybah)

The Occultation is an eschatological belief held in various denominations of Shia Islam concerning a messianic figure, the hidden and last Imam known as "the Mahdi", that one day shall return on Earth and fill the world with justice. According to the doctrine of Twelver Shīʿīsm, the main goal of Imam Mahdi will be to establish an Islamic state and to apply Islamic laws that were revealed to Muhammad. The Quran does not contain verses on the Imamate, which is the basic doctrine of Shia Islam.[31] Some Shia subsects, such as the Zaydī Shias and Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs, do not believe in the idea of the Occultation. The groups which do believe in it differ as to which lineage of the Imamate is valid, and therefore which individual has gone into Occultation. They believe there are many signs that will indicate the time of his return.

Twelver Shia Muslims believe that the prophesied Mahdi and

Hadith tradition

Shia Muslims believe that the status of Ali is supported by numerous

Holy Relics (Tabarruk)

Shia Muslims believe that the armaments and sacred items of all of the

Further, he claims that with him is the sword of the Messenger of God, his coat of arms, his Lamam (pennon) and his helmet. In addition, he mentions that with him is the flag of the Messenger of God, the victorious. With him is the Staff of Moses, the ring of Solomon, son of David, and the tray on which Moses used to offer his offerings. With him is the name that whenever the Messenger of God would place it between the Muslims and pagans no arrow from the pagans would reach the Muslims. With him is the similar object that angels brought.[35]

Al-Ṣādiq also narrated that the passing down of armaments is synonymous to receiving the Imamat (leadership), similar to how the

Other doctrines

Doctrine about necessity of acquiring knowledge

According to Muhammad Rida al-Muzaffar, God gives humans the faculty of reason and argument. Also, God orders humans to spend time thinking carefully on creation while he refers to all creations as his signs of power and glory. These signs encompass all of the universe. Furthermore, there is a similarity between humans as the little world and the universe as the large world. God does not accept the faith of those who follow him without thinking and only with imitation, but also God blames them for such actions. In other words, humans have to think about the universe with reason and intellect, a faculty bestowed on us by God. Since there is more insistence on the faculty of intellect among Shia Muslims, even evaluating the claims of someone who claims prophecy is on the basis of intellect.[36][37]

Practices

Shia religious practices, such as prayers, differ only slightly from the Sunnīs. While all

Holidays

Shia Muslims celebrate the following annual holidays:

- Eid ul-Fitr, which marks the end of fasting during the month of Ramadan

- Eid al-Adha, which marks the end of the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca

- Eid al-Ghadeer, which is the anniversary of the Ghadir Khum, the occasion when Muhammad announced Ali's Imamate before a multitude of Muslims.[38]Eid al-Ghadeer is held on the 18th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

- The Day of Ashura for Shia Muslims commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali, brother of Hasan and grandson of Muhammad, who was killed by Yazid ibn Muawiyah in Karbala (central Iraq). Ashura is a day of deep mourning which occurs on the 10th of Muharram.

- Arba'een commemorates the suffering of the women and children of Ḥusayn ibn Ali's household. After Ḥusayn was killed, they were marched over the desert, from Karbala (central Iraq) to Shaam (Damascus, Syria). Many children (some of whom were direct descendants of Muhammad) died of thirst and exposure along the route. Arbaein occurs on the 20th of Safar, 40 days after Ashura.

- 6th Shīʿīte Imam.[39]

- Fāṭimah's birthday on 20th of Jumada al-Thani. This day is also considered as the "'women and mothers' day"[40]

- Ali's birthday on 13th of Rajab.

- Sha'aban.

- Laylat al-Qadr, anniversary of the night of the revelation of the Quran.

- Eid al-Mubahila celebrates a meeting between the Ahl al-Bayt(household of Muhammad) and a Christian deputation from Najran. Al-Mubahila is held on the 24th of Dhu al-Hijjah.

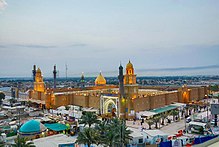

Holy sites

After

.Most of the Shīʿa sacred places and heritage sites in Saudi Arabia have been destroyed by the Al Saud-Wahhabi armies of the Ikhwan, the most notable being the tombs of the Imams located in the Al-Baqi' cemetery in 1925.[43] In 2006, a bomb destroyed the shrine of Al-Askari Mosque.[44] (See: Anti-Shi'ism).

Purity

Shia orthodoxy, particularly in Twelver Shi'ism, has considered non-Muslims as agents of impurity (Najāsat). This categorization sometimes extends to kitābῑ, individuals belonging to the People of the Book, with Jews explicitly labeled as impure by certain Shia religious scholars.[45][46][47] Armenians in Iran, who have historically played a crucial role in the Iranian economy, received relatively more lenient treatment.[46]

Shi'ite theologians and mujtahids (jurists), such as Muḥammad Bāqir al-Majlisῑ, held that Jews' impurity extended to the point where they were advised to stay at home on rainy or snowy days to prevent contaminating their Shia neighbors. Ayatollah Khomeini, Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979 to 1989, asserted that every part of an unbeliever's body, including hair, nails, and bodily secretions, is impure. However, the current leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, stated in a fatwa that Jews and other Peoples of the Book are not inherently impure, and touching the moisture on their hands does not convey impurity.[45][48][47]

History

The original Shia identity referred to the followers of Imam Ali,

Origins

The Shia, originally known as the "partisans" of Ali, Muhammad's cousin and Fatima's husband, first emerged as a distinct movement during the First Fitna from 656 to 661 CE. Shia doctrine holds that Ali was meant to lead the community after Muhammad's death in 632. Historians dispute over the origins of Shia Islam, with many Western scholars positing that Shīʿīsm began as a political faction rather than a truly religious movement.[52][53] Other scholars disagree, considering this concept of religious-political separation to be an anachronistic application of a Western concept.[54]

Shia Muslims believe that Muhammad designated Ali as his heir during a speech at Ghadir Khumm.[14] The point of contention between different Muslim sects arises when Muhammad, whilst giving his speech, gave the proclamation "Anyone who has me as his mawla, has Ali as his mawla".[9][55][56][57] Some versions add the additional sentence "O God, befriend the friend of Ali and be the enemy of his enemy".[58] Sunnis maintain that Muhammad emphasized the deserving friendship and respect for Ali. In contrast, Shia Muslims assert that the statement unequivocally designates Ali as Muhammad's appointed successor.[9][59][60][61] Shia sources also record further details of the event, such as stating that those present congratulated Ali and acclaimed him as Amir al-Mu'minin ("commander of the believers").[58]

When Muhammad died in 632 CE,

Ali's rule over the

Hasan, Husayn, and Karbala

Upon the death of Ali, his elder son

Ḥusayn ibn Ali, Ali's younger son and brother to Hasan, initially resisted calls to lead the Muslims against Mu'awiya and reclaim the caliphate. In 680 CE, Mu'awiya died and passed the caliphate to his son Yazid, and breaking the treaty with Hasan ibn Ali. Yazid asked Husayn to swear allegiance (bay'ah) to him. Ali's faction, having expected the caliphate to return to Ali's line upon Mu'awiya's death, saw this as a betrayal of the peace treaty and so Ḥusayn rejected this request for allegiance. There was a groundswell of support in Kufa for Ḥusayn to return there and take his position as caliph and Imam, so Husayn collected his family and followers in Medina and set off for Kufa.[14]

En route to Kufa, Husayn was blocked by an army of Yazid's men, which included people from Kufa, near Karbala (modern Iraq); rather than surrendering, Husayn and his followers chose to fight. In the Battle of Karbala, Ḥusayn and approximately 72 of his family members and followers were killed, and Husayn's head was delivered to Yazid in Damascus. The Shi'a community regard Husayn ibn Ali as a martyr (shahid), and count him as an Imam from the Ahl al-Bayt. The Battle of Karbala and martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali is often cited as the definitive separation between the Shia and Sunnī sects of Islam. Ḥusayn is the last Imam following Ali mutually recognized by all branches of Shia Islam.[66] The martyrdom of Husayn and his followers is commemorated on the Day of Ashura, occurring on the tenth day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar.[14]

Imamate of the Ahl al-Bayt

Later, most denominations of Shia Islam, including Twelvers and Ismāʿīlīs, became Imamis.[9][68][69] Imami Shīʿītes believe that Imams are the spiritual and political successors to Muhammad.[70] Imams are human individuals who not only rule over the Muslim community with justice, but also are able to keep and interpret the divine law and its esoteric meaning. The words and deeds of Muhammad and the Imams are a guide and model for the community to follow; as a result, they must be free from error and sin, and must be chosen by divine decree (nass) through Muhammad.[71][72] According to this view peculiar to Shia Islam, there is always an Imam of the Age, who is the divinely appointed authority on all matters of faith and law in the Muslim community. Ali was the first Imam of this line, the rightful successor to Muhammad, followed by male descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah.[70][73]

This difference between following either the

It is believed in Twelver and Ismāʿīlī branches of Shia Islam that

Imam Mahdi, last Imam of the Shia

In Shia Islam, Imam

Dynasties

In the century following the Battle of Karbala (680 CE), as various Shia-affiliated groups diffused in the emerging Islamic world, several nations arose based on a Shia leadership or population.

- Zaydi dynasty in what is now Morocco.

- Ismaili Iranian dynasty. Their headquarters were in Eastern Arabia and Bahrain. It was founded by Abu Sa'id al-Jannabi.

- Twelver Iraniandynasty. at its peak consisted of large portions of modern-day Iran and Iraq.

- al-Jazira, northern Syria and Iraq.

- Hulagu, in territories in Western and Central Asia which today comprise most of Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and Pakistan. The Ilkhanate initially embraced many religions, but was particularly sympathetic to Buddhism and Christianity. Later Ilkhanate rulers, beginning with Ghazan in 1295, chose Islam as the state religion; his brother Öljaitü promoted Shia Islam.[77]

Fatimid Caliphate

- Fatimids (909–1171 CE): Controlled much of North Africa, the Levant, parts of Arabia, and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The group takes its name from Fāṭimah, Muhammad's daughter, from whom they claim descent.

- In 909 CE, the Shia military leader Abu Abdallah al-Shiʻi overthrew the Sunni rulers in North Africa, an event which led to the foundation of the Fatimid Caliphate.[80]

- Egypt,[81] founded the city of Cairo[82] and the al-Azhar Mosque. A Greek slave by origin, he was freed by al-Muʻizz.[83]

Safavid Empire

A major turning point in the history of Shia Islam was the dominion of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in Persia. This caused a number of changes in the Muslim world:

- The ending of the relative mutual tolerance between Sunnīs and Shias that existed from the time of the Mongol conquestsonwards and the resurgence of antagonism between the two groups.

- Initial dependence of Shīʿīte clerics on the state followed by the emergence of an independent body of ulama capable of taking a political stand different from official policies.[86]

- The growth in importance of

- The growth of the Islamic prophet Muhammadduring his lifetime) are to be bases for verdicts, rejecting the use of reasoning.

With the fall of the Safavids, the state in Persia—including the state system of courts with government-appointed

-

The declaration ofSafavid Persia

-

Monument commemorating the Battle of Chaldiran, where more than 7,000 Muslims of the Shia and Sunnī sects killed each other

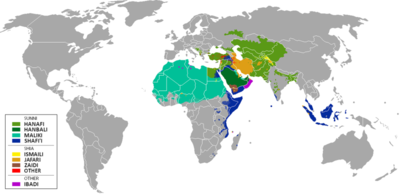

Demographics

Shia Islam is the second largest branch of Islam.[90] It is estimated that either 10–20%[91] or 10–13%[92][93][94] of the global Muslim population are Shias. They may number up to 200 million as of 2009.[93] As of 1985, Shia Muslims are estimated to be 21% of the Muslim population in South Asia, although the total number is difficult to estimate.[95]

Shia Muslims form a distinct majority of the population in two countries of the Muslim world: Azerbaijan and Iran.[96][97] Shia Muslims constitute 36.3% of the entire population (and 38.6% of the Muslim population) of the Middle East.[98]

Estimates have placed the proportion of Shia Muslims in Lebanon between 27% and 45% of the population,

Significant Shia communities also exist in the coastal regions of

A significant

Significant populations worldwide

Figures indicated in the first three columns below are based on the October 2009 demographic study by the Pew Research Center report, Mapping the Global Muslim Population.[93][94]

| Country | Article | Shia population in 2009 (Pew)[93][94] | Percent of population that is Shia in 2009 (Pew)[93][94] | Percent of global Shia population in 2009 (Pew)[93][94] | Population estimate ranges and notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam in Iran | 66,000,000–69,500,000 | 90–95 | 37–40 | ||

Pakistan

|

Shia Islam in the Indian subcontinent | 25,272,000 | 15 | 15 | A 2010 estimate was that Shia made up about 10–15% of Pakistan's population.[115] |

Shi'a Islam in Iraq

|

19,000,000–24,000,000 | 55–65 | 10–11 | ||

India

|

Shia Islam in the Indian subcontinent | 12,300,000–18,500,000 | 1.3–2 | 9–14 | |

| Shia Islam in Yemen | 7,000,000–8,000,000 | 35–40 | ~5 | Majority following Zaydi Shia sect.

| |

Shi'a Islam in Turkey

|

6,000,000–9,000,000 | ~10–15 | ~3–4 | Majority following Alevi Shia sect. | |

| Islam in Azerbaijan | 4,575,000–5,590,000 | 45–55 | 2–3 | Azerbaijan is majority Shia.[116][117][118] A 2012 work noted that in Azerbaijan, among believers of all faiths, 10% identified as Sunni, 30% identified as Shia, and the remainder of followers of Islam simply identified as Muslim.[118] | |

Shi'a Islam in Afghanistan

|

3,000,000 | 15 | ~2 | A reliable census has not been taken in Afghanistan in decades, but about 20% of Afghan population is Shia, mostly among ethnic Tajik and Hazara minorities.[119] | |

| Islam in Syria | 2,400,000 | 13 | ~2 | Majority following Alawites Shia sect. | |

Shi'a Islam in Lebanon

|

2,100,000 | 31.2 | <1 | In 2020, the CIA World Factbook stated that Shia Muslims constitute 31.2% of Lebanon's population.[120] | |

Shi'a Islam in Saudi Arabia

|

2,000,000 | ~6 | |||

Shi'a Islam in Nigeria

|

<2,000,000 | <1 | <1 | Estimates range from as low as 2% of Nigeria's Muslim population to as high as 17% of Nigeria's Muslim population. Islamic Movement in Nigeria, an Iranian-inspired Shia organization led by Ibrahim Zakzaky.[121]

| |

| Islam in Tanzania | ~1,500,000 | ~2.5 | <1 | ||

Shi'a Islam in Kuwait

|

500,000–700,000 | 20–25 | <1 | Among Kuwait's estimated 1.4 million citizens, about 30% are Shia (including Ahmadi, whom the Kuwaiti government count as Shia). Among Kuwait's large expatriate community of 3.3 million noncitizens, about 64% are Muslim, and among expatriate Muslims, about 5% are Shia.[123]

| |

| Islam in Bahrain | 400,000–500,000 | 65–70 | <1 | ||

Shi'a Islam in Tajikistan

|

~400,000 | ~4 | <1 | Shi'a Muslims in Tajikistan are predominantly Nizari Ismaili | |

| Islam in Germany | ~400,000 | ~0.5 | <1 | ||

| Islam in the United Arab Emirates | ~300,000 | ~3 | <1 | ||

| Islam in the United States Shia Islam in the Americas |

~225,000 | ~0.07 | <1 | Shi'a form a majority amongst Arab Muslims in many American cities, e.g. Lebanese Shi'a forming the majority in Detroit.[124] | |

| Islam in the United Kingdom | ~125,000 | ~0.2 | <1 | ||

| Islam in Qatar | ~100,000 | ~3.5 | <1 | ||

| Islam in Oman | ~100,000 | ~2 | <1 | As of 2015, about 5% of Omanis are Shia (compared to about 50% Ibadi and 45% Sunni).[125]

|

Major denominations or branches

The Shia community throughout its history split over the issue of the Imamate. The largest branch are the

Twelver

Twelver Shīʿīsm or Ithnāʿashariyyah is the largest branch of Shia Islam,

Doctrine

Twelver doctrine is based on

- Monotheism: God is one and unique;

- Justice: the concept of moral rightness based on ethics, fairness, and equity, along with the punishment of the breach of these ethics;

- Prophethood: the institution by which God sends emissaries, or prophets, to guide humankind;

- Leadership: a divine institution which succeeded the institution of Prophethood. Its appointees (Imams) are divinely appointed;

- Resurrection and Last Judgment: God's final assessment of humanity.

Books

Besides the

- Nahj al-Balagha by Ash-Sharif Ar-Radhi[138]– the most famous collection of sermons, letters & narration attributed to Ali, the first Imam regarded by Shias

- Muhammad ibn Ya'qub al-Kulayni[139]

- Wasa'il al-Shiʻah by al-Hurr al-Amili

The Twelve Imams

According to the theology of Twelvers, the successor of Muhammad is an infallible human individual who not only rules over the Muslim community with justice but also is able to keep and interpret the divine law (sharīʿa) and its esoteric meaning. The words and deeds of Muhammad and the Twelve Imams are a guide and model for the Muslim community to follow; as a result, they must be free from error and sin, and Imams must be chosen by divine decree (nass) through Muhammad.[71][72] The twelfth and final Imam is Hujjat Allah al-Mahdi, who is believed by Twelvers to be currently alive and hidden in Occultation.[76]

Jurisprudence

The Twelver jurisprudence is called

The

- Tawḥīd: unity and oneness of God;

- Nubuwwah: prophethood of Muhammad;

- Muʿad: resurrection and final judgment;

- ʿAdl: justice of God;

- Imamah: the rightful place of the Shīʿīte Imams.

In Jaʿfari jurisprudence, there are eight secondary pillars, known as Furu ad-Din, which are as follows:[137]

- Salat(prayer);

- Sawm(fasting);

- Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca;

- Zakāt (alms giving to the poor);

- Jihād (struggle) for the righteous cause;

- Directing others towards good;

- Directing others away from evil;

- Khums (20% tax on savings yearly, after deduction of commercial expenses).

According to Twelvers, defining and interpretation of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is the responsibility of Muhammad and the Twelve Imams. Since the 12th Imam is currently in Occultation, it is the duty of Shīʿīte clerics to refer to the Islamic literature, such as the Quran and hadith, and identify legal decisions within the confines of Islamic law to provide means to deal with current issues from an Islamic perspective. In other words, clergymen in Twelver Shīʿīsm are believed to be the guardians of fiqh, which is believed to have been defined by Muhammad and his twelve successors. This process is known as ijtihad and the clerics are known as marjaʿ, meaning "reference"; the labels Allamah and Ayatollah are in use for Twelver clerics.

Islamists

Isma'ili (Sevener)

After the death or Occultation of

Though there are several subsects amongst the Isma'ilis, the term in today's vernacular generally refers to the Shia Imami Isma'ili Nizārī community, often referred to as the Isma'ilis by default, who are followers of the Aga Khan and the largest group within Isma'ilism. Another Shia Imami Isma'ili community are the Dawudi Bohras, led by a Da'i al-Mutlaq ("Unrestricted Missionary") as representative of a hidden Imam. While there are many other branches with extremely differing exterior practices, much of the spiritual theology has remained the same since the days of the faith's early Imams. In recent centuries, Isma'ilis have largely been an Indo-Iranian community,[146] but they can also be found in India, Pakistan, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia,[147] Yemen, Jordan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East and South Africa, and in recent years several Isma'ilis have emigrated to China,[148] Western Europe (primarily in the United Kingdom), Australia, New Zealand, and North America.[149]

Isma'ili Imams

In the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī interpretation of Shia Islam, the Imam is the guide and the intercessor between humans and God, and the individual through whom God is recognized. He is also responsible for the esoteric interpretation of the Quran (taʾwīl). He is the possessor of divine knowledge and therefore the "Prime Teacher". According to the "Epistle of the Right Path", a Persian Isma'ili prose text from the post-Mongol period of Isma'ili history, by an anonymous author, there has been a chain of Imams since the beginning of time, and there will continue to be an Imam present on the Earth until the end of time. The worlds would not exist in perfection without this uninterrupted chain of Imams. The proof (hujja) and gate (bāb) of the Imam are always aware of his presence and are witness to this uninterrupted chain.[150]

After the death of

In 909 CE,

The second split occurred between

The

Pillars

Ismāʿīlīs have categorized their practices which are known as seven pillars:

|

|

|

Contemporary leadership

The Nizārīs place importance on a scholarly institution because of the existence of a present Imam. The Imam of the Age defines the jurisprudence, and his guidance may differ with Imams previous to him because of different times and circumstances. For Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs, the current Imam is Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV. The Nizārī line of Imams has continued to this day as an uninterrupted chain.

Divine leadership has continued in the Bohra branch through the institution of the "Missionary" (

Zaydī (Fiver)

Zaydism, otherwise known as Zaydiyya or as Zaydī Shīʿism, is a branch of Shia Islam named after Zayd ibn Ali. Followers of the Zaydī school of jurisprudence are called Zaydīs or occasionally Fivers. However, there is also a group called Zaydī Wāsiṭīs who are Twelvers (see below). Zaydīs constitute roughly 42–47% of the population of Yemen.[159][160]

Doctrine

The Zaydīs, Twelvers, and Ismāʿīlīs all recognize the same first four Imams; however, the Zaydīs consider Zayd ibn Ali as the 5th Imam. After the time of Zayd ibn Ali, the Zaydīs believed that any descendant (Sayyid) of Hasan ibn Ali or Husayn ibn Ali could become the next Imam, after fulfilling certain conditions.[161] Other well-known Zaydī Imams in history were Yahya ibn Zayd, Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya, and Ibrahim ibn Abdullah.

The Zaydī doctrine of Imamah does not presuppose the infallibility of the Imam, nor the belief that the Imams are supposed to receive divine guidance. Moreover, Zaydīs do not believe that the Imamate must pass from father to son but believe it can be held by any Sayyid descended from either Hasan ibn Ali or Husayn ibn Ali (as was the case after the death of the former). Historically, Zaydīs held that Zayd ibn Ali was the rightful successor of the 4th Imam since he led a rebellion against the Umayyads in protest of their tyranny and corruption. Muhammad al-Baqir did not engage in political action, and the followers of Zayd ibn Ali maintained that a true Imam must fight against corrupt rulers.

Jurisprudence

In matters of

Timeline

The

The

Currently, the most prominent Zaydī political movement is the

Persecution of Shia Muslims

The history of Shia–Sunnī relations has often involved religious discrimination, persecution, and violence, dating back to the earliest development of the two competing sects. At various times throughout the history of Islam,

Militarily established and holding control over the Umayyad government, many Sunnī rulers perceived the Shias as a threat—both to their political and religious authority.

In 1514, the

During the rule of Saddam Hussein's Ba'athist Iraq, Shia political activists were arrested, tortured, expelled or killed, as part of a crackdown launched after an assassination attempt against Iraq's Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz in 1980.[193][194] In March 2011, the Malaysian government declared Shia Islam a "deviant" sect and banned Shia Muslims from promoting their faith to other Muslims, but left them free to practice it themselves privately.[195][196]

The most recent campaign of anti-Shia oppression was the

See also

- Alawites

- Anti-Shi'ism

- Criticism of Twelver Shia Islam

- History of Shia Islam

- Imamate in Shia doctrine

- Imamate and guardianship of Ali ibn Abi Talib

- Imamate in Ismaili doctrine

- Imamate in Nizari doctrine

- Imamate in Twelver doctrine

- Intellectual proofs in Shia jurisprudence

- List of Shia books

- List of Shia Islamic dynasties

- List of Shia Muslim scholars of Islam

- List of Shia Muslims

- Shia clergy

- Shia crescent

- Shia genocide

- Shia Islam in the Indian subcontinent

- Shia nations

- Shia Rights Watch

- Shia view of Ali

- Shia view of the Quran

References

Notes

- ^ A 2019 Council on Foreign Relations article states: "Nobody really knows the size of the Shia population in Nigeria. Credible estimates that its numbers range between 2 and 3 percent of Nigeria's population, which would amount to roughly four million."[121] A 2019 BBC News article said that "Estimates of [Nigerian Shia] numbers vary wildly, ranging from less than 5% to 17% of Nigeria's Muslim population of about 100 million."[122]

Citations

- ISBN 978-1-7936-2136-8.

- ISBN 978-1-7936-2136-8.

- ^ ISBN 0-85229-663-0, Vol. 10, p. 738

- ISBN 978-1-4411-4645-8.

- ^ Wehr, Hans. "Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic" (4th ed.). p. 598.

- ^ Shiʻa is an alternative spelling of Shia, and Shiʻite of Shiite. In subsequent sections, the spellings Shia and Shiite are adopted for consistency, except where the alternative spelling is in the title of a reference.

- ^ "Difference Between The Meaning Of Shia And Shiite? However the term Shiite is being used less and is considered less proper than simply using the term "Shia"". English forums. 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Tabataba'i 1977, p. 34

- ^ the Imams, divinely guided leaders of the Shiʿi communities, sinless, and granted special insight into the Qurʾanic text. The theology of the Imams that developed over the next several centuries made little distinction between the authority of the Imams to politically lead the Muslim community and their spiritual prowess; quite to the contrary, their right to political leadership was grounded in their special spiritual insight. While in theory, the only just ruler of the Muslim community was the Imam, the Imams were politically marginal after the first generation. In practice, Shiʿi Muslims negotiated varied approaches to both interpretative authority over Islamic texts and governance of the community, both during the lifetimes of the Imams themselves and even more so following the disappearance of the twelfth and final Imamin the ninth century.

- ^ Sobhani & Shah-Kazemi 2001, p. 97

- ^ Sobhani & Shah-Kazemi 2001, p. 98

- OCLC 59136662.

- ^ Cornell 2007, p. 218

- ^ ISBN 978-0-02-865603-8.

- ^ "Druze and Islam". americandruze.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ "Ijtihad in Islam". AlQazwini.org. Archived from the original on 2 January 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 15

- ^ Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). "Shiʻite Doctrine". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ ISBN 0-87779-044-2, LoC: BL31.M47 1999, p. 525

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 46

- ^ "Encyclopedia of the Middle East". Mideastweb.org. 14 November 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ "اضافه شدن نام حضرت علی (ع) به شهادتین". fa. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-1412839723.

- ^ Francis Robinson, Atlas of the Muslim World, p. 47.

- ^ "Shīʿite". Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Quran 33:33

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 155

- ^ Corbin (1993), pp. 48, 49

- ^ Corbin (1993), p. 48

- ^ "How do Sunnis and Shias differ theologically?". BBC. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-88706-843-0

- ^ "Compare Shia and Sunni Islam". ReligionFacts. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-59257-222-9, p. 135

- ^ Shiʻite Islam, by Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i (1979), pp. 41–44 [ISBN missing]

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9914308-6-4.[page needed]

- ^ Allamah Muhammad Rida Al Muzaffar (1989). The faith of Shia Islam. Ansariyan Qum. p. 1.

- ^ "The Beliefs of Shia Islam – Chapter 1". Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ISBN 978-0791417812.

- ISBN 978-0838910047.

- ^ "Lady Fatima inspired women of Iran to emerge as an extraordinary force". 18 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Karbala and Najaf: Shia holy cities". 20 April 2003.

- Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 3 June 2002. Retrieved 12 November 2006.)

according to a famous hadith... 'our sixth imam, Imam Sadeg, says that we have five definitive holy places that we respect very much. The first is Mecca... second is Medina... third... is in Najaf. The fourth... in Kerbala. The last one belongs to... Qom.'

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link - ISBN 978-0231700405.

- ISBN 978-1841622439. Archived from the originalon 2 January 2017.

- ^ a b Tsadik, Daniel (1 October 2010), "Najāsat", Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, Brill, retrieved 8 January 2024

- ^ ISBN 978-1-138-21322-7.

- ^ a b Moreen, Vera B. (1 October 2010), "Shiʽa and the Jews", Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, Brill, retrieved 8 January 2024

- ^ "Jews and Wine in Shiite Iran – Some Observations on the Concept of Religious Impurity". Association for Iranian Studies. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "Shiʻite Islam", by Allamah Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i, translated by Sayyid Husayn Nasr, State University of New York Press, 1975, p. 24

- ^ Dakake (2008), pp. 1–2

- ^ In his "Mutanabbi devant le siècle ismaëlien de l'Islam", in Mém. de l'Inst Français de Damas, 1935, p.

- ^ See: Lapidus p. 47, Holt p. 72

- ^ Francis Robinson, Atlas of the Islamic World, p. 23.

- ISBN 978-0-19-579387-1

- ^ Newman, Andrew J. Shiʿi. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 40

- ^ "From the article on Shii Islam in Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Oxfordislamicstudies.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-1-4928-5884-3. Archivedfrom the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ "The Shura Principle in Islam – by Sadek Sulaiman". www.alhewar.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Sunnis and Shia: Islam's ancient schism". BBC News. 4 January 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ISBN 0-85229-663-0, Vol. 10, p. tid738

- ^ ""Solhe Emam Hassan"-Imam Hassan Sets Peace". Archived from the original on 11 March 2013.

- ^ تهذیب التهذیب. p. 271.

- ^ Madelung, Wilfred (2003). "Ḥasan b. ʿAli b. Abi Ṭāleb". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Discovering Islam: making sense of Muslim history and society (2002) Akbar S. Ahmed

- ^ Mustafa, Ghulam (1968). Religious trends in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. p. 11. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

Similarly, swords were also placed on the Idols, as it is related that Harith b. Abi Shamir, the Ghassanid king, had presented his two swords, called Mikhdham and Rasub, to the image of the goddess, Manat....to note that the famous sword of Ali, the fourth caliph, called Dhu-al-Fiqar, was one of these two swords

- ^ "Lesson 13: Imam's Traits". Al-Islam.org. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015.

- .

- ^ a b "امامت از منظر متکلّمان شیعی و فلاسفه اسلامی". پرتال جامع علوم انسانی (in Persian). Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b Nasr (1979), p. 10

- ^ a b Momen 1985, p. 174

- ^ عسکری, سید مرتضی. ولایت علی در قرآن کریم و سنت پیامبر، مرکز فرهنگی انتشاراتی منیر، چاپ هفتم.

- ^ Corbin 1993, pp. 45–51

- ^ Nasr (1979), p. 15

- ^ ISBN 978-0-02-865604-5.

- ^ "نقد و بررسى گرایش ایلخانان به اسلام و تشیّع". پرتال جامع علوم انسانی (in Persian). Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "The Five Kingdoms of the Bahmani Sultanate". orbat.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ Ansari, N.H. Bahmanid Dynasty. Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- ISBN 978-0-15-501197-7.

The architect of his military system was a general named Jawhar, an islamicized Greek slave who had led the conquest of North Africa and then of Egypt

- ISBN 978-0-521-26645-1.

When the Sicilian Jawhar finally entered Fustat in 969 and the following year founded the new dynastic capital, Cairo, 'The Victorious', the Fatimids ...

- ISBN 978-0-415-05914-5.

Under Muʼizz (955-975) the Fatimids reached the height of their glory, and the universal triumph of Isma ʻilism appeared not far distant. The fourth Fatimid Caliph is an attractive character: humane and generous, simple and just, he was a good administrator, tolerant and conciliatory. Served by one of the greatest generals of the age, Jawhar al-Rumi, a former Greek slave, he took fullest advantage of the growing confusion in the Sunnite world.

- ^ LCCN 2008020716. Archivedfrom the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7. Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Francis Robinson, Atlas of the Muslim World, p. 49.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 123

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 130, 191

- ^ "Jurisprudence and Law – Islam: Reorienting the Veil". University of North Carolina. 2009.

- ^ a b c "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

The Pew Forum's estimate of the Shia population (10–13%) is in keeping with previous estimates, which generally have been in the range of 10–15%.

- CIA. The World Factbook. 2010. Archived from the originalon 4 June 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

Shia Islam represents 10–20% of Muslims worldwide

- ^ "Shīʿite". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

In the early 21st century some 10–13 percent of the world's 1.6 billion Muslims were Shiʿi.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

Of the total Muslim population, 10–13% are Shia Muslims and 87–90% are Sunni Muslims. Most Shias (between 68% and 80%) live in just four countries: Iran, Pakistan, India and Iraq.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 277

- ^ a b "Foreign Affairs – When the Shiites Rise – Vali Nasr". Mafhoum.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Quick guide: Sunnis and Shias". BBC News. 11 December 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008.

- ISBN 978-1-4262-0221-6.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2010". U.S. Government Department of State. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- US State Department. 2012.

- ^ "The New Middle East, Turkey, and the Search for Regional Stability" (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute. April 2008. p. 87. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7007-1606-7.

- ^ "Country Profile: Pakistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Pakistan. Library of Congress. February 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

Religion: The overwhelming majority of the population (96.3 percent) is Muslim, of whom approximately 95 percent are Sunni and 5 percent Shia.

- ^ "Shia women too can initiate divorce" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

Religion: Virtually the entire population is Muslim. Between 80 and 85 percent of Muslims are Sunni and 15 to 19 percent, Shia.

- ^ "Afghanistan". Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook on Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

Religions: Sunni Muslim 80%, Shia Muslim 19%, other 1%

- ^ al-Qudaihi, Anees (24 March 2009). "Saudi Arabia's Shia press for rights". BBC Arabic Service. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ Merrick, Jane; Sengupta, Kim (20 September 2009). "Yemen: The land with more guns than people". The Independent. London. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ^ Sharma, Hriday (30 June 2011). "The Arab Spring: The Initiating Event for a New Arab World Order". E-international Relations. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020.

In Yemen, Zaidists, a Shia offshoot, constitute 30% of the total population

- ISBN 978-1-4379-4439-6. Archivedfrom the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Paul Ohia (16 November 2010). "Nigeria: 'No Settlement With Iran Yet'". This Day. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-9987080939.

- ISBN 978-3-89958-406-6. Archivedfrom the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- ^ Yasurō Hase; Hiroyuki Miyake; Fumiko Oshikawa (2002). South Asian migration in comparative perspective, movement, settlement and diaspora. Japan Center for Area Studies, National Museum of Ethnology. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Pakistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2 December 2021.

- ^ Reynolds, James (12 August 2012). "Why Azerbaijan is closer to Israel than Iran". BBC.

- ^ Umutlu, Ayseba. "Islam's gradual resurgence in post-Soviet Azerbaijan".

- ^ ISBN 978-1138650817.

- ^ Massoud, Waheed (6 December 2011). "Why have Afghanistan's Shias been targeted now?". BBC.

- ^ "Lebanon". CIA World Factbook. 2020.

- ^ a b Campbell, John (10 July 2019). "More Trouble Between Nigeria's Shia Minority and the Police". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ Tangaza, Haruna Shehu (5 August 2019). "Islamic Movement in Nigeria: The Iranian-inspired Shia group". BBC.

- Office of International Religious Freedom, United States Department of State.

- ^ Aswad, B. and Abowd, T., 2013. Arab Americans. Race and Ethnicity: The United States and the World, pp. 272–301.

- ^ Erlich, Reese (4 August 2015). "Mitigating Sunni-Shia conflict in 'the world's most charming police state'". Agence France-Presse.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-7833-4. Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-7965-2.

- ^ Tabataba'i (1979), p. 76

- ^ God's rule: the politics of world religions, p. 146, Jacob Neusner, 2003

- ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 40

- ^ Cornell 2007, p. 237

- ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 45.

- ^ "Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan – Presidential Library – Religion" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-19-515713-0. p. 45

- ^ "Challenges For Saudi Arabia Amidst Protests in the Gulf – Analysis". Eurasia Review. 25 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012.

- ^ "Shiʿite Doctrine". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0778791423.

- ^ Nahj al-balaghah, Mohaghegh (researcher) 'Atarodi Ghoochaani, the introduction of Sayyid Razi, p. 1

- ISBN 978-1-939420-00-8.

- ^ Khalaji 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Bohdan 2020, p. 243.

- ^ "اخوانی گوشهنشین". ایرنا پلاس (in Persian). 1 March 2020. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Bohdan 2020, pp. 250–251.

- S2CID 143672216.

- ^ "Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsa'i". Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- ^ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p. 76

- ^ "Congressional Human Rights Caucus Testimony – Najran, The Untold Story". Archived from the original on 27 December 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ "News Summary: China; Latvia". 22 September 2003. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-0687-0.

- S2CID 170748666.

- ^ ISSN 1874-6691.

- OCLC 47785421.

- ^ "al-Hakim bi Amr Allah: Fatimid Caliph of Egypt". Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ISBN 978-1-78831-559-3.

- ISBN 978-1-906999-25-4.

[Druze] often they are not regarded as being Muslim at all, nor do all the Druze consider themselves as Muslim

- ^ "Are the Druze People Arabs or Muslims? Deciphering Who They Are". Arab America. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-135-98079-5.

Most Druze do not consider themselves Muslim. Historically they faced much persecution and keep their religious beliefs secrets.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-0687-0.

- ^ "About Yemen". Yemeni in Canada. Embassy of the Republic of Yemen in Canada. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "Yemen [Yamaniyyah]: general data of the country". Population Statistics. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "Sunni-Shiʻa Schism: Less There Than Meets the Eye". 1991. p. 24. Archived from the original on 23 April 2005.

- ^ Hodgson, Marshall (1961). Venture of Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 262.[clarification needed]

- ^ Ibn Abī Zarʻ al-Fāsī, ʻAlī ibn ʻAbd Allāh (1340). Rawḍ al-Qirṭās: Anīs al-Muṭrib bi-Rawd al-Qirṭās fī Akhbār Mulūk al-Maghrib wa-Tārīkh Madīnat Fās. ar-Rabāṭ: Dār al-Manṣūr (published 1972). p. 38.

- ^ "حين يكتشف المغاربة أنهم كانوا شيعة وخوارج قبل أن يصبحوا مالكيين !". hespress.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-691-10099-9.

- ]

- ^ "The Initial Destination of the Fatimid caliphate: The Yemen or The Maghrib?". iis.ac.uk. The Institute of Ismaili Studies. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015.

- ^ "Shiʻah tenets concerning the question of the imamate – New Page 1". muslimphilosophy.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012.

- ^ Article by Sayyid 'Ali ibn 'Ali Al-Zaidi,At-tarikh as-saghir 'an ash-shia al-yamaniyeen (Arabic: التاريخ الصغير عن الشيعة اليمنيين, A short History of the Yemenite Shiʻites), 2005 Referencing: Iranian Influence on Moslem Literature

- ^ Article by Sayyid 'Ali ibn 'Ali Al-Zaidi, At-tarikh as-saghir 'an ash-shia al-yamaniyeen (Arabic: التاريخ الصغير عن الشيعة اليمنيين, A short History of the Yemenite Shiʻites), 2005 Referencing: Encyclopædia Iranica

- ISBN 978-1-86064-321-7.

- ^ Madelung, W. (7 December 2007). "al-Uk̲h̲ayḍir". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Article by Sayyid Ali ibn ' Ali Al-Zaidi, At-tarikh as-saghir 'an ash-shia al-yamaniyeen (Arabic: التاريخ الصغير عن الشيعة اليمنيين, A short History of the Yemenite Shiʻites), 2005

- ^ "Universiteit Utrecht Universiteitsbibliotheek". Library.uu.nl. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ S2CID 213121908.

- ^ a b c Glenn, Cameron (29 April 2015). "Who are Yemen's Houthis?". The Islamists. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthis form own government in Sanaa". Al Jazeera. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ "Yemen govt vows to stay in Aden despite IS bombings". Yahoo News. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Arab Coalition Faces New Islamic State Foe in Yemen Conflict". NDTV.com. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ ISSN 1874-6691.

- ^ ISSN 2077-1444.

- ^ ISSN 1573-0255.

- ^ a b Bunzel, Cole (March 2015). "From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State" (PDF). The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. 19. Washington, D.C.: Center for Middle East Policy (Brookings Institution): 1–48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-8261-2857-7.

- ^ Maddox, Bronwen (30 December 2006). "Hanging will bring only more bloodshed". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Al-Ahram Weekly | Region | Shiʻism or schism". Weekly.ahram.org.eg. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ "The Shia, Ted Thornton, NMH, Northfield Mount Hermon". Archived from the original on 13 August 2009.

- ^ "The Origins of the Sunni/Shia split in Islam". Islamfortoday.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-393-06211-3pp. 52–53

- ISBN 0-8160-6577-2

- ^ Al-e Ahmad, Jalal. Plagued by the West (Gharbzadegi), translated by Paul Sprachman. Delmor, NY: Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University, 1982.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia – The Saud Family and Wahhabi Islam". Library of Congress Country Studies. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ Gritten, David (25 February 2006). "Long path to Iraq's sectarian split". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (25 April 2003). "Christian outsider in Saddam's inner circle". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Malaysian government to Shia Muslims: Keep your beliefs to yourself". globalpost.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia" (PDF). International Religious Freedom Report. United States Department of State Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- S2CID 195448888. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Ghasemi, Faezeh (2020). Anti-Shiism Discourse (PhD). University of Tehran.

• Ghasemi, Faezeh (2017). "Anti-Shiite and Anti-Iranian Discourses in ISIS Texts". Discourse. 11 (3): 75–96.

• Matthiesen, Toby (21 July 2015). "The Islamic State Exploits Entrenched Anti-Shia Incitement". Sada. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-275-98732-9.

- Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Columbia University Center for Iranian Studies. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Martin, Richard C. (2004). Encyclopaedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Vol. 1: Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World: A–L. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-02-865604-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7103-0416-2.

- Dakake, Maria Massi (2008). The Charismatic Community: Shiʻite Identity in Early Islam. Suny Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7033-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-29136-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-511915-2.

- ISBN 978-1-86064-780-2.

- ISBN 978-0-87395-272-9.

- Ṭabataba'i, Allamah Sayyid Muḥammad Husayn (1977). Shiʻite Islam. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-390-0.

- Vaezi, Ahmad (2004). Shia political thought. London: Islamic Centre of England. OCLC 59136662.

Further reading

- Chelkowski, Peter J. (2010). Eternal Performance: Taziyah and Other Shiite Rituals. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1-906497-51-4.

- ISBN 978-0-674-06428-7.

- Halm, Heinz (2004). Shiʻism. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1888-0.

- Halm, Heinz (2007). The Shiʻites: A Short History. Markus Wiener Pub. ISBN 978-1-55876-437-8.

- Lalani, Arzina R. (2000). Early Shiʻi Thought: The Teachings of Imam Muhammad Al-Baqir. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-434-4.

- Marcinkowski, Christoph (2010). Shiʻite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts. Lit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-643-80049-7.

- ISBN 978-0-300-03499-8.

- ISBN 978-964-438-320-5.

- ISBN 978-0-88706-843-0.

- ISBN 978-1-58567-896-9.

- Wollaston, Arthur N. (2005). The Sunnis and Shias. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4254-7916-9.

- Moosa, Matti (1988). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2411-0.

- Shi'a Minorities in the Contemporary World: Migration, Transnationalism and Multilocality. United Kingdom, Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (27 November 2009). "The Dilemmas of Pan-Islamic Unity". Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. 9: 64–79.

- Bohdan, Siarhei (Summer 2020). ""They Were Going Together with the Ikhwan": The Influence of Muslim Brotherhood Thinkers on Shi'i Islamists during the Cold War". The Middle East Journal. 74 (2): 243–262. S2CID 225510058.

External links

- "Shi'a History and Identity". shiism.wcfia.harvard.edu. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Project on Shi'ism and Global Affairs at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (Harvard University). 2022. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Daftary, Farhad; Nanji, Azim (2018) [2006]. "What is Shi'a Islam?". www.iis.ac.uk. London: Institute of Ismaili Studies at the Aga Khan Centre. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Muharrami, Ghulam-Husayn (2003). "History of Shi'ism: From the Advent of Islam up to the End of Minor Occultation". Al-Islam.org. Translated by Limba, Mansoor L. Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Ayatullāh Jaʿfar Subḥānī. "Shia Islam: History and Doctrines". United Kingdom: Shafaqna (International Shia News Agency). Retrieved 18 April 2023.