Shingles

| Shingles | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Herpes zoster |

Shingles vaccine[1] | |

| Medication | Aciclovir (if given early), pain medication[3] |

| Frequency | 33% (at some point)[1] |

| Deaths | 6,400 (with chickenpox)[5] |

Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a

Shingles is caused by the

The disease has been recognized since

It is estimated that about a third of people develop shingles at some point in their lives.[1] While shingles is more common among older people, children may also get the disease.[13] According to the US National Institutes of Health, the number of new cases per year ranges from 1.2 to 3.4 per 1,000 person-years among healthy individuals to 3.9 to 11.8 per 1,000 person-years among those older than 65 years of age.[8][17] About half of those living to age 85 will have at least one attack, and fewer than 5% will have more than one attack.[1][18] Although symptoms can be severe, risk of death is very low: 0.28 to 0.69 deaths per million.[10]

Signs and symptoms

The earliest symptoms of shingles, which include headache, fever, and malaise, are nonspecific, and may result in an incorrect diagnosis.[8][19] These symptoms are commonly followed by sensations of burning pain, itching, hyperesthesia (oversensitivity), or paresthesia ("pins and needles": tingling, pricking, or numbness).[20] Pain can be mild to severe in the affected dermatome, with sensations that are often described as stinging, tingling, aching, numbing or throbbing, and can be interspersed with quick stabs of agonizing pain.[21]

Shingles in children is often painless, but people are more likely to get shingles as they age, and the disease tends to be more severe.[22]

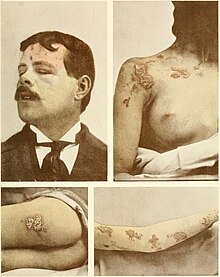

In most cases, after one to two days—but sometimes as long as three weeks—the initial phase is followed by the appearance of the characteristic skin rash. The pain and rash most commonly occur on the torso but can appear on the face, eyes, or other parts of the body. At first, the rash appears similar to the first appearance of hives; however, unlike hives, shingles causes skin changes limited to a dermatome, normally resulting in a stripe or belt-like pattern that is limited to one side of the body and does not cross the midline.[20] Zoster sine herpete ("zoster without herpes") describes a person who has all of the symptoms of shingles except this characteristic rash.[23]

Later the rash becomes

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 5 | Day 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Face

Shingles may have additional symptoms, depending on the dermatome involved. The

Shingles oticus, also known as

Shingles may occur in the mouth if the maxillary or mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve is affected,

Disseminated shingles

In those with deficits in immune function, disseminated shingles may occur (wide rash).[1] It is defined as more than 20

Pathophysiology

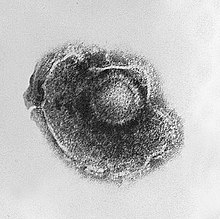

The causative agent for shingles is the

Shingles occurs only in people who have been previously infected with VZV; although it can occur at any age, approximately half of the cases in the United States occur in those aged 50 years or older.

The disease results from virus particles in a single sensory ganglion switching from their latent phase to their active phase. there are no methods to find dormant virus in the ganglia of living people.

Unless the

As with chickenpox and other forms of alpha-herpesvirus infection, direct contact with an active rash can spread the virus to a person who lacks immunity to it. This newly infected individual may then develop chickenpox, but will not immediately develop shingles.[20]

The complete sequence of the viral genome was published in 1986.[47]

Diagnosis

If the rash has appeared, identifying this disease (making a differential diagnosis) requires only a visual examination, since very few diseases produce a rash in a dermatomal pattern (sometimes called by doctors on TV "a dermatonal map"). However, herpes simplex virus (HSV) can occasionally produce a rash in such a pattern (zosteriform herpes simplex).[48][49]

When the rash is absent (early or late in the disease, or in the case of zoster sine herpete), shingles can be difficult to diagnose.[50] Apart from the rash, most symptoms can occur also in other conditions.

Laboratory tests are available to diagnose shingles. The most popular test detects VZV-specific

Differential diagnosis

Shingles can be confused with

Prevention

Shingles risk can be reduced in children by the

A review by Cochrane concluded that Zostavax was useful for preventing shingles for at least three years.[7] This equates to about 50% relative risk reduction. The vaccine reduced rates of persistent, severe pain after shingles by 66% in people who contracted shingles despite vaccination.[58] Vaccine efficacy was maintained through four years of follow-up.[58] It has been recommended that people with primary or acquired immunodeficiency should not receive the live vaccine.[58]

Two doses of Shingrix are recommended, which provide about 90% protection at 3.5 years.[37][57] As of 2016, it had been studied only in people with an intact immune system.[14] It appears to also be effective in the very old.[14]

In the UK, shingles vaccination is offered by the National Health Service (NHS) to all people in their 70s. As of 2021[update] Zostavax is the usual vaccine, but Shingrix vaccine is recommended if Zostavax is unsuitable, for example for those with immune system issues. Vaccination is not available to people over 80 as "it seems to be less effective in this age group".[59][60] By August 2017, just under half of eligible 70–78 year olds had been vaccinated.[61] About 3% of those eligible by age have conditions that suppress their immune system, and should not receive Zostavax.[62] There had been 1,104 adverse reaction reports by April 2018.[62] In the US, it is recommended that healthy adults 50 years and older receive two doses of Shingrix, two to six months apart.[37][63]

Treatment

The aims of treatment are to limit the severity and duration of pain, shorten the duration of a shingles episode, and reduce complications. Symptomatic treatment is often needed for the complication of postherpetic neuralgia.[64] However, a study on untreated shingles shows that, once the rash has cleared, postherpetic neuralgia is very rare in people under 50 and wears off in time; in older people, the pain wore off more slowly, but even in people over 70, 85% were free from pain a year after their shingles outbreak.[65]

Analgesics

People with mild to moderate pain can be treated with

Antivirals

Steroids

Corticosteroids do not appear to decrease the risk of long-term pain.[16] Side effects however appear to be minimal. Their use in Ramsay Hunt syndrome had not been properly studied as of 2008.[69]

Zoster ophthalmicus

Treatment for

Prognosis

The rash and pain usually subside within three to five weeks, but about one in five people develop a painful condition called

There is a slightly increased risk of developing cancer after a shingles episode. However, the mechanism is unclear and mortality from cancer did not appear to increase as a direct result of the presence of the virus.[73] Instead, the increased risk may result from the immune suppression that allows the reactivation of the virus.[74]

Although shingles typically resolves within 3–5 weeks, certain complications may arise:

- Secondary bacterial infection.[9]

- Motor involvement,[9] including weakness especially in "motor herpes zoster".[75]

- Eye involvement: trigeminal nerve involvement (as seen in herpes ophthalmicus) should be treated early and aggressively as it may lead to blindness. Involvement of the tip of the nose in the zoster rash is a strong predictor of herpes ophthalmicus.[76]

- Postherpetic neuralgia, a condition of chronic pain following shingles.

Epidemiology

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) has a high level of infectivity and has a worldwide prevalence.[77] Shingles is a re-activation of latent VZV infection: zoster can only occur in someone who has previously had chickenpox (varicella).

Shingles has no relationship to season and does not occur in epidemics. There is, however, a strong relationship with increasing age.[22][44] The incidence rate of shingles ranges from 1.2 to 3.4 per 1,000 person‐years among younger healthy individuals, increasing to 3.9–11.8 per 1,000 person‐years among those older than 65 years,[8][22] and incidence rates worldwide are similar.[8][78] This relationship with age has been demonstrated in many countries,[8][78][79][80][81][82] and is attributed to the fact that cellular immunity declines as people grow older.

Another important risk factor is

There is no strong evidence for a genetic link or a link to family history. A 2008 study showed that people with close relatives who had shingles were twice as likely to develop it themselves,[90] but a 2010 study found no such link.[87]

Adults with latent VZV infection who are exposed intermittently to children with chickenpox receive an immune boost.[22][87] This periodic boost to the immune system helps to prevent shingles in older adults. When routine chickenpox vaccination was introduced in the United States, there was concern that, because older adults would no longer receive this natural periodic boost, there would be an increase in the incidence of shingles.

Multiple studies and surveillance data, at least when viewed superficially, demonstrate no consistent trends in incidence in the U.S. since the chickenpox vaccination program began in 1995.[91] However, upon closer inspection, the two studies that showed no increase in shingles incidence were conducted among populations where varicella vaccination was not as yet widespread in the community.[92][93] A later study by Patel et al. concluded that since the introduction of the chickenpox vaccine, hospitalization costs for complications of shingles increased by more than $700 million annually for those over age 60.[94] Another study by Yih et al. reported that as varicella vaccine coverage in children increased, the incidence of varicella decreased, and the occurrence of shingles among adults increased by 90%.[95] The results of a further study by Yawn et al. showed a 28% increase in shingles incidence from 1996 to 2001.[96] It is likely that incidence rate will change in the future, due to the aging of the population, changes in therapy for malignant and autoimmune diseases, and changes in chickenpox vaccination rates; a wide adoption of zoster vaccination could dramatically reduce the incidence rate.[8]

In one study, it was estimated that 26% of those who contract shingles eventually present complications. Postherpetic neuralgia arises in approximately 20% of people with shingles.[97] A study of 1994 California data found hospitalization rates of 2.1 per 100,000 person-years, rising to 9.3 per 100,000 person-years for ages 60 and up.[98] An earlier Connecticut study found a higher hospitalization rate; the difference may be due to the prevalence of HIV in the earlier study, or to the introduction of antivirals in California before 1994.[99]

History

Shingles has a long recorded history, although historical accounts fail to distinguish the blistering caused by VZV and those caused by smallpox,[36] ergotism, and erysipelas. In the late 18th century William Heberden established a way to differentiate shingles and smallpox,[100] and in the late 19th century, shingles was differentiated from erysipelas. In 1831 Richard Bright hypothesized that the disease arose from the dorsal root ganglion, and an 1861 paper by Felix von Bärensprung confirmed this.[101]

Recognition that chickenpox and shingles were caused by the same virus came at the beginning of the 20th century. Physicians began to report that cases of shingles were often followed by chickenpox in younger people who lived with the person with shingles. The idea of an association between the two diseases gained strength when it was shown that lymph from a person with shingles could induce chickenpox in young volunteers. This was finally proved by the first isolation of the virus in

Until the 1940s the disease was considered benign, and serious complications were thought to be very rare.[104] However, by 1942, it was recognized that shingles was a more serious disease in adults than in children and that it increased in frequency with advancing age. Further studies during the 1950s on immunosuppressed individuals showed that the disease was not as benign as once thought, and the search for various therapeutic and preventive measures began.[105] By the mid-1960s, several studies identified the gradual reduction in cellular immunity in old age, observing that in a cohort of 1,000 people who lived to the age of 85, approximately 500 (i.e., 50%) would have at least one attack of shingles, and 10 (i.e., 1%) would have at least two attacks.[106]

In historical shingles studies, shingles incidence generally increased with age. However, in his 1965 paper, Hope-Simpson suggested that the "peculiar age distribution of zoster may in part reflect the frequency with which the different age groups encounter cases of varicella and because of the ensuing boost to their antibody protection have their attacks of zoster postponed".[22] Lending support to this hypothesis that contact with children with chickenpox boosts adult cell-mediated immunity to help postpone or suppress shingles, a study by Thomas et al. reported that adults in households with children had lower rates of shingles than households without children.[107] Also, the study by Terada et al. indicated that pediatricians reflected incidence rates from 1/2 to 1/8 that of the general population their age.[108]

Etymology

The family name of all the

Research

Until the mid-1990s, infectious complications of the central nervous system (CNS) caused by VZV reactivation were regarded as rare. The presence of rash, as well as specific neurological symptoms, were required to diagnose a CNS infection caused by VZV. Since 2000, PCR testing has become more widely used, and the number of diagnosed cases of CNS infection has increased.[118]

Classic textbook descriptions state that VZV reactivation in the CNS is restricted to immunocompromised individuals and the elderly; however, studies have found that most participants are immunocompetent, and younger than 60 years old. Historically, vesicular rash was considered a characteristic finding, but studies have found that rash is only present in 45% of cases.[118] In addition, systemic inflammation is not as reliable an indicator as previously thought: the mean level of C-reactive protein and mean white blood cell count are within the normal range in participants with VZV meningitis.[119] MRI and CT scans are usually normal in cases of VZV reactivation in the CNS. CSF pleocytosis, previously thought to be a strong indicator of VZV encephalitis, was absent in half of a group of people diagnosed with VZV encephalitis by PCR.[118]

The frequency of CNS infections presented at the emergency room of a community hospital is not negligible, so a means of diagnosing cases is needed. PCR is not a foolproof method of diagnosis, but because so many other indicators have turned out to not be reliable in diagnosing VZV infections in the CNS, screening for VZV by PCR is recommended. Negative PCR does not rule out VZV involvement, but a positive PCR can be used for diagnosis, and appropriate treatment started (for example, antivirals can be prescribed rather than antibiotics).[118]

The introduction of DNA analysis techniques has shown some complications of varicella-zoster to be more common than previously thought. For example, sporadic meningoencephalitis (ME) caused by varicella-zoster was regarded as rare disease, mostly related to childhood chickenpox. However, meningoencephalitis caused by varicella-zoster is increasingly recognized as a predominant cause of ME among immunocompetent adults in non-epidemic circumstances.[120]

Diagnosis of complications of varicella-zoster, particularly in cases where the disease reactivates after years or decades of latency, is difficult. A rash (shingles) can be present or absent. Symptoms vary, and there is a significant overlap in symptoms with herpes-simplex symptoms.[120]

Although DNA analysis techniques such as

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0990449119. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2020..

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain - ^ a b c d "Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Signs & Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1 May 2014. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ PMID 23863052.

- ^ "Herpes Zoster Diagnosis, Testing, Lab Methods". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). April 2022. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- PMID 27733281.

- ISBN 978-8131238004. Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ PMID 37781954.

- ^ PMID 17143845.

- ^ PMID 26478818.

- ^ PMID 35340552.

- ^ "Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Researchers discover how chickenpox and shingles virus remains dormant". UCLH Biomedical Research Centre. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Overview". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ S2CID 46480440.

- PMID 24500927.

- ^ PMID 38050854.

- from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ISBN 978-1437735932. Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- from the original on 3 November 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010. Revised June 2005.

- ^ PMID 10794584. Archived from the originalon 29 September 2007.

- ^ PMID 15307000.

- ^ PMID 14267505.

- S2CID 29270135.

- ^ "Shingles (herpes zoster)". Department of Health. New York State. January 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ PMID 26096121.

- ISBN 978-0702046957. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ PMID 12676845.

- ^ ISBN 978-1437721973. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ ]

- PMID 24999086.

- PMID 26073188.

- ISBN 978-0721629216.

- ^ "Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Varicella-zoster virus". Public Health Agency of Canada. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ S2CID 6691444.

- ^ PMID 18021864.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ PMID 25794504.

- PMID 14583142.

- S2CID 34582060.

- PMID 12491156.

- (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2008.

- PMID 7618983.

- ^ PMID 14720565.

- ^ "Shingles". NHS.UK. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- PMID 17631237.

- PMID 3018124.

- (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2014.

- PMID 3022586.

- PMID 15334402.

- (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2008.

- S2CID 24215093.

- PMID 27563537.

- PMID 19252116.

- S2CID 184486904.*Lay summary in: "Two-for-One: Chickenpox Vaccine Lowers Shingles Risk in Children". Scientific American. 11 June 2019.

- PMID 18528318. Archived from the original on 17 November 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2010..

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain - ^ PMID 27626517.

- ^ PMID 21998225.

- ^ "Shingles vaccine overview". NHS (UK). 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2021. Overview to be reviewed 31 August 2024.

- ^ "The shingles immunisation programme: evaluation of the programme and implementation in 2018" (PDF). Public Health England (PHE). 9 April 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "Herpes zoster (shingles) immunisation programme 2016 to 2017: evaluation report". GOV.UK. 15 December 2017. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b Shaun Linter (18 April 2018). "NHS England warning as vaccine programme extended". Health Service Journal. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ "Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Vaccination". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 25 October 2018. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ PMID 18021865.

- PMID 11009518.

- S2CID 24555396.

- S2CID 5296437.

- PMID 24500927.

- PMID 18646170.

- PMID 10919899.

- PMID 3012334.

- S2CID 476280.

- PMID 15328522.

- PMID 6979711.

- S2CID 26443976.

- ^ Roat MI (September 2014). "Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus". Merck Manual. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- S2CID 20844136.

- ^ PMID 17939895. Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- PMID 11693508.

- PMID 16050886.

- PMID 17976353.

- (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- PMID 3335810.

- PMID 1308664.

- PMID 28829784.

- S2CID 37086354.

- ^ S2CID 31667542.

- PMID 9852978.

- S2CID 7583608.

- PMID 18490586.

- PMID 17585291. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011..

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain - PMID 15897984.

- PMID 15897983.

- S2CID 21934553.

- PMID 15960856.

- PMID 17976353.

- (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- S2CID 25626718.

- PMID 17488884. Archived from the originalon 13 January 2008.

- ISBN 978-0521660242.

- PMID 10520948.

- S2CID 28771357.

- ^ "Evelyn Nicol 1930 - 2020 - Obituary". legacy.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Holt LE, McIntosh R (1936). Holt's Diseases of Infancy and Childhood. D Appleton Century Company. pp. 931–933.

- ISBN 978-0306448553.

- PMID 14267505.

- S2CID 28385365.

- PMID 7594784.

- Perseus Project.

- ^ ἕρπειν in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "herpes". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Herpes | Define Herpes at Dictionary.com". Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ ζωστήρ in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "zoster". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "shingles". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- PMID 23999562.

- ^ from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- PMID 18680414.

- ^ S2CID 3321888.

- (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2013.

Further reading

- Saguil A (November 2017). "Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia: Prevention and Management". American Family Physician. 96 (10): 656–663. PMID 29431387.